Martha Raye’s obituary in 1994 in “The Independent”:

THE WIDE-MOUTHED, clarion-voiced Martha Raye disliked being called a comedienne. ‘I’m a clown,’ she invariably maintained. Although she wasn’t born in a trunk, Raye was born backstage. Her parents were Reed and Hooper, well-known vaudevillians, and she joined the act at the age of three. At 15, she took a job as vocalist with Paul Ash’s orchestra, changing her name from Margie Reed to Martha Raye, a name she found by jabbing a pin into a telephone book. ‘Just think,’ she said. ‘I coulda wound up bein’ called ‘Mercy Hospital]’ ‘

After leaving the band, she developed a night-club act. In 1936 she was booked into the Trocadero in Hollywood, where the film director Norman Taurog saw her and offered a screen test. The songwriter Sam Coslow also caught her act and was so impressed he wrote her a song, ‘Mr Paganini’. She sang it in her successful test and in the first film of her Paramount contract, the Bing Crosby musical Rhythm on the Range. ‘For Miss Raye it was an exceptional break,’ Variety wrote. ‘She has an opportunity to show off all her tricks, particularly the mugging . . . She impresses as a very promising picture comedienne.’ The public agreed, and Raye adopted ‘Mr Paganini’ as her signature tune.

She made 15 films for Paramount, including Waikiki Wedding and Double or Nothing (both Crosby vehicles), two editions of the Big Broadcast series, and three films with Bob Hope: College Swing (1938), Give Me a Sailor (1938) and Never Say Die (1939). Her first film as a freelance was Universal’s screen version of Rodgers and Hart’s The Boys From Syracuse (1940).

Since 1936 Raye had been appearing on radio with Al Jolson, and in 1940 they co-starred in the Broadway musical Hold Onto Your Hats. The show was a hit, but Jolson’s health wasn’t up to a New York winter, and Hats closed after 158 performances. Back in Hollywood, Raye played twins in Abbott and Costello’s Keep ‘Em Flying (1941), prompting one critic to write ‘I’m not sure the world is ready for two Martha Rayes.’

In 1942 Raye, Carole Landis, Kay Francis and Mitzi Mayfair spent six months entertaining servicemen in Britain and North Africa. Long after her three co-stars had returned to Hollywood, Raye continued the tour, ending up with a severe case of malaria.

In 1944, she, Landis, Francis and Mayfair played themselves in 20th Century-Fox’s Four Jills in a Jeep, based on a book ‘written’ by Landis.

Raye stayed at 20th to play a night-club singer in the Betty Grable vehicle Pin-Up Girl (1944). She clowned with her Fellow BigMouth Joe E. Brown and sang two relentlessly patriotic songs, ‘Red Robins, Bob Whites and Blue Birds’ and ‘Yankee Doodle Hayride’ (‘There ain’t gonna be no hoedown / Till we knock the foe down]’). Also in the film were the two dancing Condos Brothers, one of whom (Nick) was the fourth of Raye’s seven husbands.

It was her uproarious performance in Four Jills in a Jeep that prompted Charles Chaplin to cast her as the dim-witted lottery winner Annabella Bonheur in Monsieur Verdoux (1947). At first overawed by Chaplin, Raye realised that hero-worship was repressing her performance, and started calling him ‘Chuck’. Amused by this, he countered by calling her ‘Maggie’.

Soon she felt so secure she would shout ‘Lunch]’ when she thought the morning’s filming had gone on too long. Chaplin still grinned and bore it, realising that the scenes in which Verdoux attempts to murder the indestructible Annabella were the funniest in the film. Ironically, Raye’s association with the politically unpopular Chaplin hindered, rather than helped her career, and she wasn’t offered another movie for 15 years. After more than a decade in television, she returned to the big screen as the fortune-teller Madame Lulu in MGM’s Jumbo (1962).

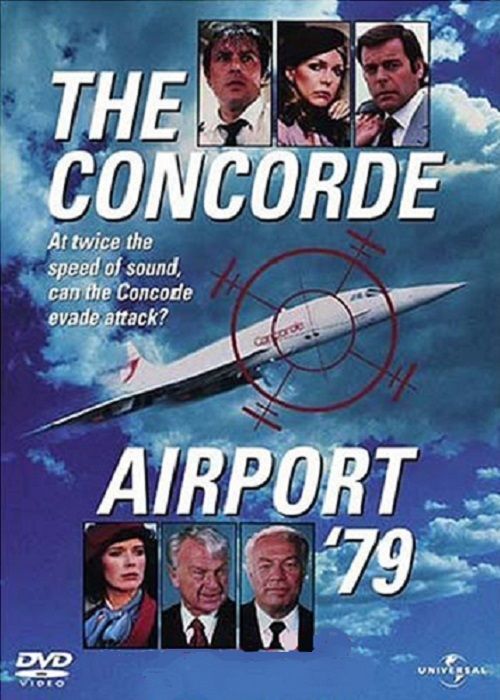

In 1967 she was one of the stars who followed Carol Channing in the Broadway production of Hello, Dolly. More television followed, including McMillan and Wife, for which she received an Emmy Award nomination. In 1979 she returned to Universal to play Boss Witch in Pufnstuf and a weak- bladdered passenger in Airport ’79 – the Concorde. Asked when she planned to retire, she replied ‘When I’m dead.’ In late 1993 a stroke which paralysed her left leg necessitated amputation. A week later she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom for entertaining troops during the Second World War, the Korean war and in Vietnam – where she was wounded twice. In 1992 she sued the makers of For the Boys (1991), claiming her life was used as the basis of the Bette Midler film. In February the suit was dismissed.

In 1968, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences presented her with the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award for her selfless entertaining in three wars. After the ceremony, a tearful Martha Raye was asked by photographers to kiss her Oscar. She refused, saying, ‘If I did, I’d swallow it.’