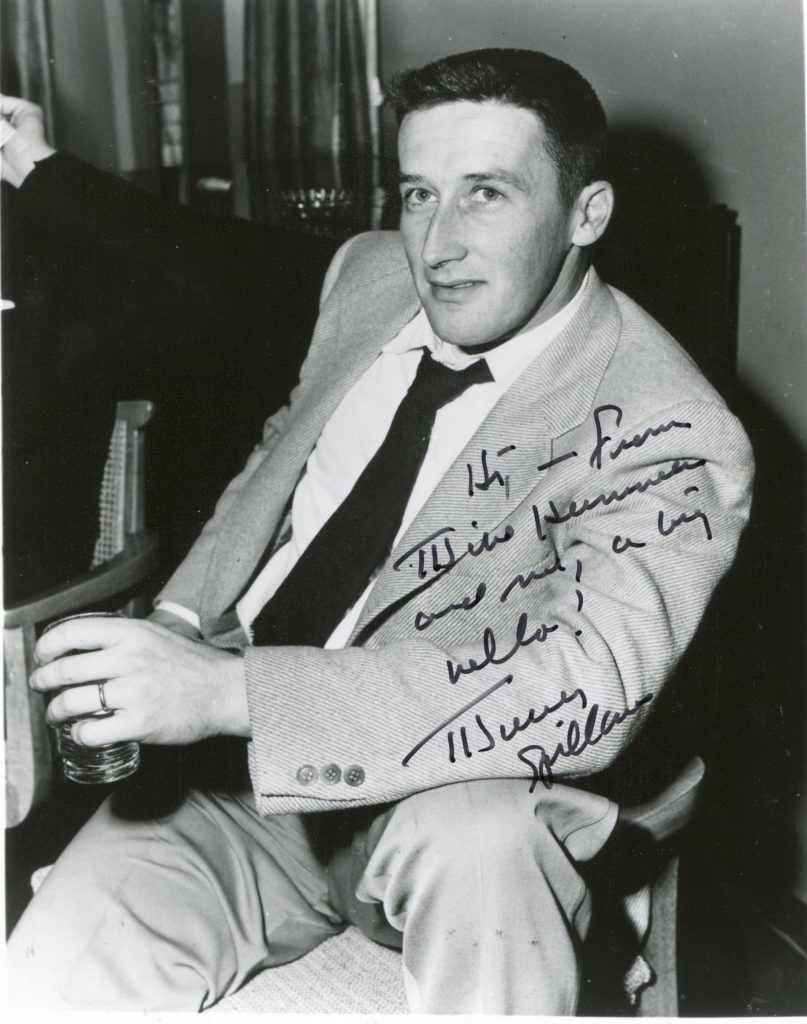

Frank Morrison Spillane (March 9, 1918 – July 17, 2006), better known as Mickey Spillane, was an American crime novelist, whose stories often feature his signature detective character, Mike Hammer. More than 225 million copies of his books have sold internationally. Spillane was also an occasional actor, once even playing Hammer himself

Mickey Spillane obituary in The Guardian in 2006.

Pulp writer whose tales of tough guys and cute broads made him the bestselling novelist of the 20th century

‘Women,” he claimed in later life, “liked the name Mickey.” Other accounts suggest that Michael was the middle name his Catholic father had him baptised under; Morrison was the name his Protestant mother put on his birth certificate. Few at his fraught christening would have foreseen the arrival of the 20th century’s bestselling novelist, Mickey Spillane, who has died aged 88.

His father, John Joseph Spillane, was an Irish-American bartender. Young Frank was brought up in the “very tough” neighbourhood of Elizabeth, New Jersey. Under the superintendence of his mother, Catherine, the Spillane home was less tough. He claimed to have read all Melville and Dumas before he was 11. After Erasmus Hall high school, Brooklyn, he went to Kansas State College (now Fort Hays State University), starred briefly on the football field and dropped out. In the de rigueur way, he kicked around in the depression 1930s, working for a while as a Long Island lifeguard – “women” liked that too.

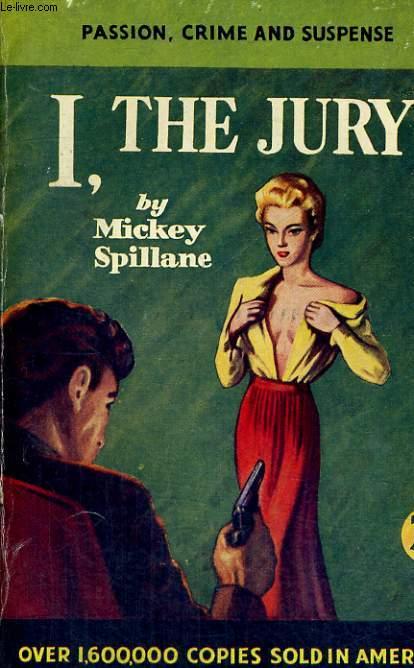

In 1935 he began submitting work to “slick” (ie illustrated) magazines, “working my way down”, as he later recalled, “to the comic books: Captain Marvel, Captain America, Superman, Batman – you name it, I did them all.” It was, he thought, “a great training ground for writers. You couldn’t beat it.” Fast-order work would be Spillane’s speciality. I, the Jury (1947) was written in nine days. When the car containing his manuscript of The Body Lovers was stolen two decades later, he claimed to be only concerned about the loss of his wheels: “the missing manuscript just means another three days’ work.”

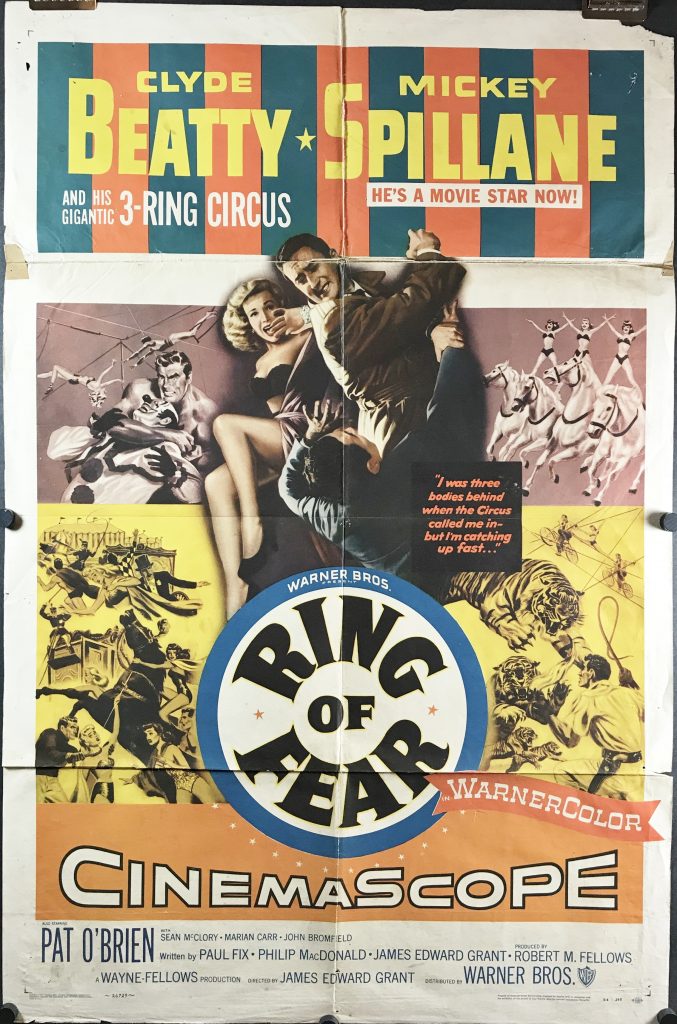

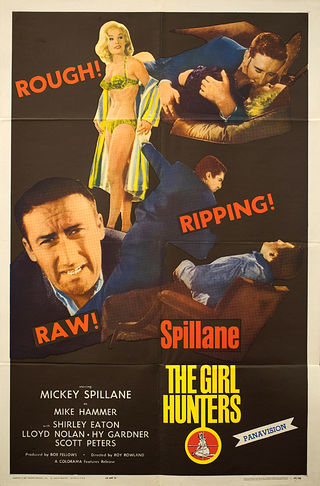

Spillane served in the US army airforce during the second world war, enlisting the day after Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941. By his own account, he flew fighter missions and taught cadets how to fly. In interviews he claimed two bullet wounds and a civilian knife scar sustained while working undercover with the FBI to break up a narcotics ring. On demobilisation he worked in Barnum and Bailey’s circus as a trampoline artist (the setting is used in his 1962 novel, The Girl Hunters) and claimed a professional proficiency with throwing knives. More profitably, he returned to writing.

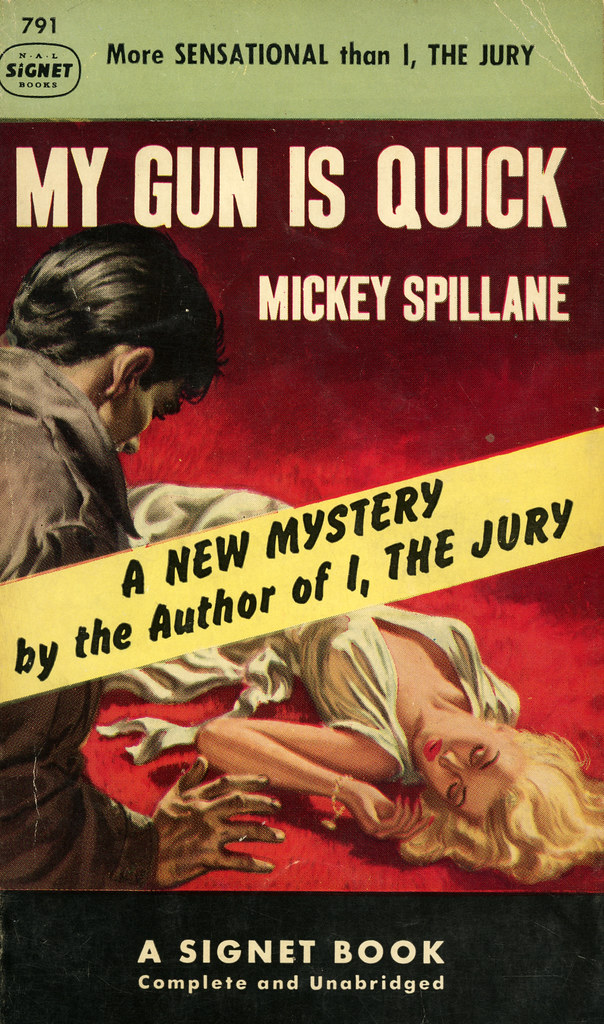

Story-magazines were losing ground to paperback originals – pulp novels selling to the masses at 25 cents. Spillane duly turned out I, the Jury. It drew on the hard-boiled, private investigator tradition pioneered by Black Mask magazine in the 1930s, although the most famous product of that coterie, Raymond Chandler, disdained Spillane as a writing gorilla: “pulp writing at its worst was never as bad as this stuff”.

Spillane himself acknowledged the influence of only one crime writer, the now-obscure John Carroll Daly, creator of the private eye Race Williams. He flaunted his lack of authorial polish, claiming (mischievously) never to introduce characters with moustaches or who drank cognac because he could not spell the words. I, the Jury introduced the series hero Mike Hammer, whose tough-talking, woman-beating, whisky-swilling machismo answered the needs of the postwar “male action” market.

Estimates suggest global sales of around 200 million. By 1980, seven of the top 15 all-time bestselling fiction titles in America were by Spillane. “People like them,” he blandly explained.

Hammer is less a detective than an ultra-violent vigilante. I, the Jury lays down the formula. Mike’s marine “buddy” Jack, who lost an arm saving Hammer’s life in the Pacific, is sadistically murdered. Hammer sets out to avenge him, skirting the niceties of the law, vowing to his friend’s corpse: “I’m going to get the louse that killed you. He won’t sit in the [electric] chair. He won’t hang. He will die exactly as you died, with a .45 slug in the gut, just a little below the belly button.” So it goes – even though “he” turns out to be a gorgeous “she”. Spillane astutely exploited the market he had created with Hammer with Vengeance Is Mine (1950), My Gun Is Quick (1950), The Big Kill (1951) and Kiss Me, Deadly (1952). All hit the mark.

It is never clear how Spillane’s hero supports himself – or how he pays Velda, his faithful secretary with the “million-dollar legs”. Prodigious cocksman though he is, Hammer respects Velda too much to take sexual advantage of her, although she loves him madly. “Broads” and “hoods” are never in short supply. Hammer is always outnumbered by the criminal enemy: “There are ten thousand mugs that hate me … they hate me because if they mess with me I shoot their damn heads off.”

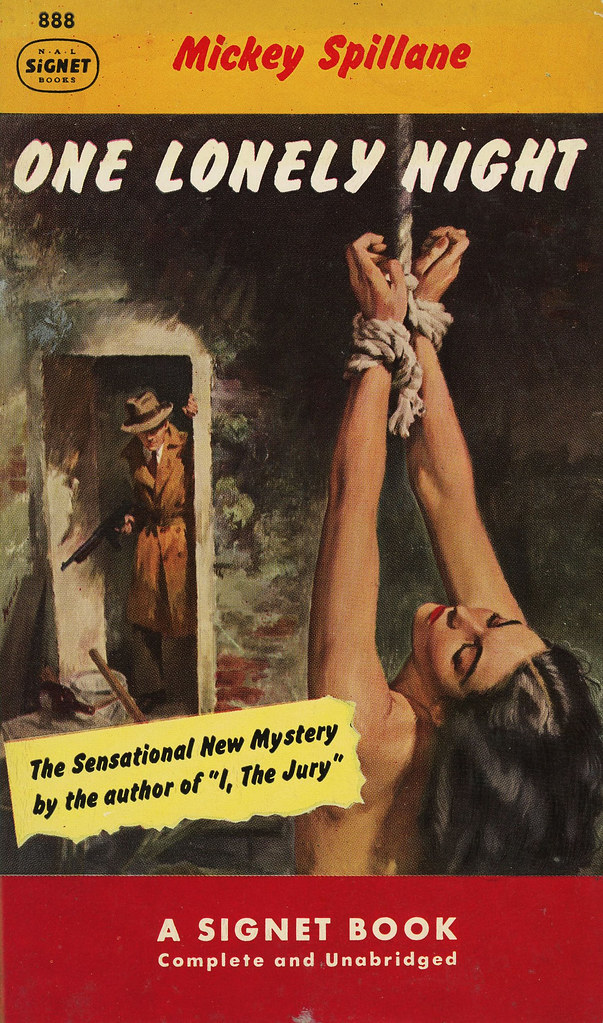

The climax of a Mike Hammer narrative invariably features sadistic execution. The most hilarious is in Vengeance is Mine, which ends with the line (just before she/he gets it in the gut) “Juno was a Man!”. The link was often made between Spillane and Joe McCarthy, and over the years Hammer’s victims were as likely to be “reds” as “hoods”. In One Lonely Night (1951), the hero mows down 40 communists with a machine-gun (originally there were 80, but the publishers “thought that was too gory”).

Spillane regarded himself as a super-patriot, and was so regarded by others. John Wayne gave him a Jaguar XK140 for his anti-communism and Ayn Rand (author of Atlas Shrugged) commended his prose style to her disciples. Spillane’s patriotism was, however, always tinged with a pessimistic, quasi-religious sense of doom, and in the early 1960s he predicted a race war in America.

The Hammer novels are written as spoken monologue and are stylistically direct. Spillane had great faith in the slam-bang opening, believing that “the first page sells the book”. He claimed never to read galleys or rewrite. He had, however, an odd compulsiveness about punctuation, and once insisted that 50,000 copies of Kiss Me, Deadly be pulped after the comma was left out of the title.

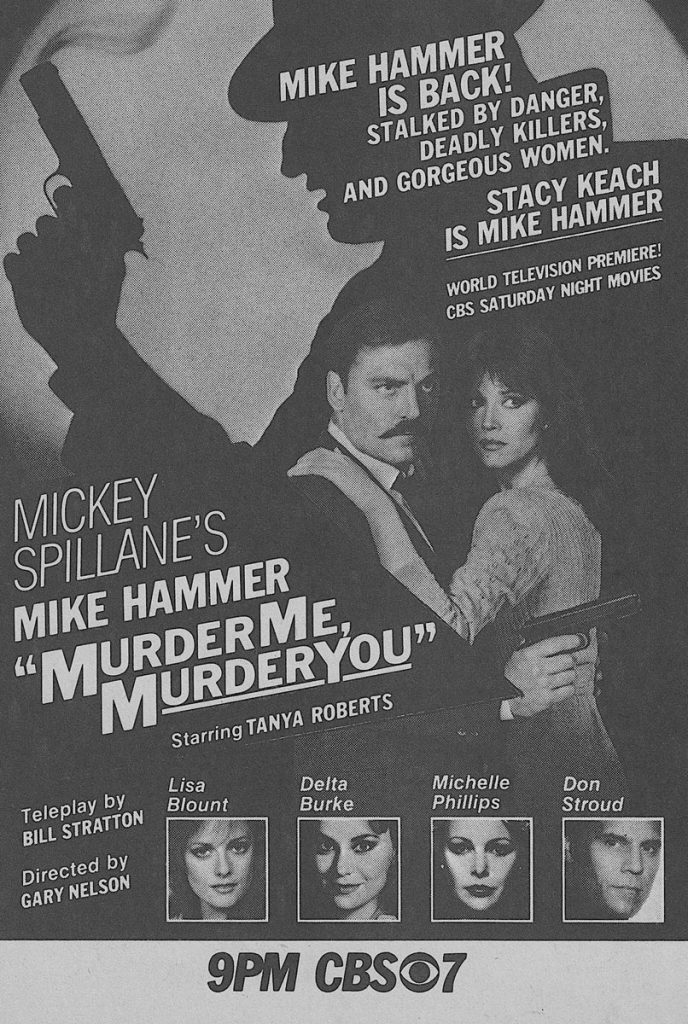

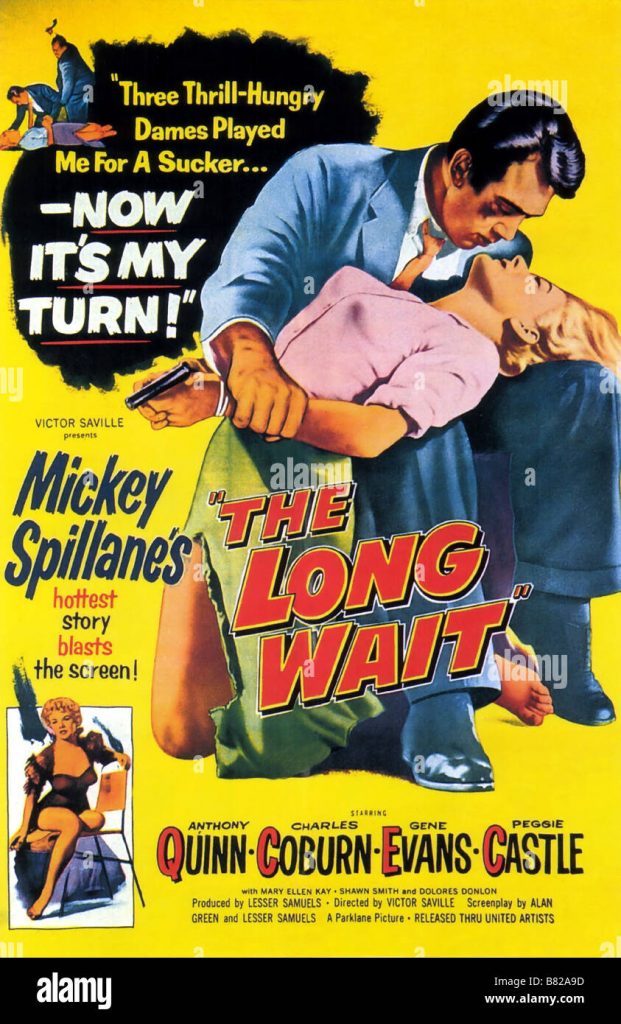

The Hammer novels enjoyed new leases of life in film, radio, comic-strip and television adaptation. I, the Jury was filmed twice (1953, 1982), as were other Hammer books. The only film that has any distinction is Robert Aldrich’s exaggeratedly noir Kiss Me Deadly (1955). Spillane disliked it – not least because of the missing comma. Possessed of ruggedly good looks, he himself played Hammer in the film of The Girl Hunters (1963), turning in a commendable performance. He also played cameo roles in other films.

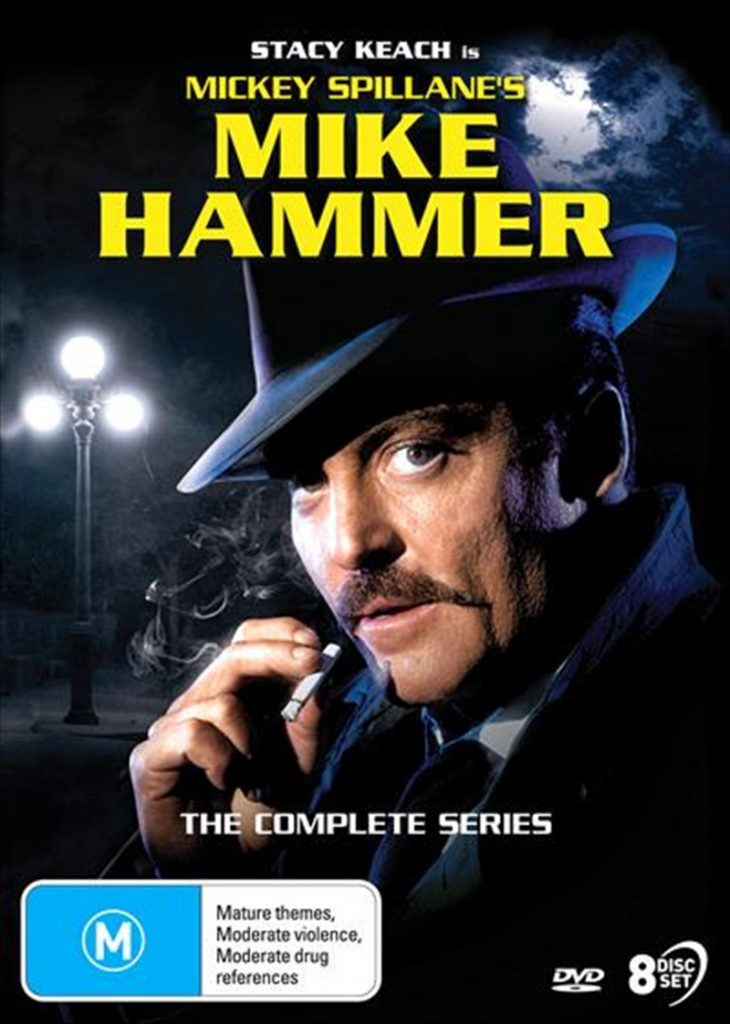

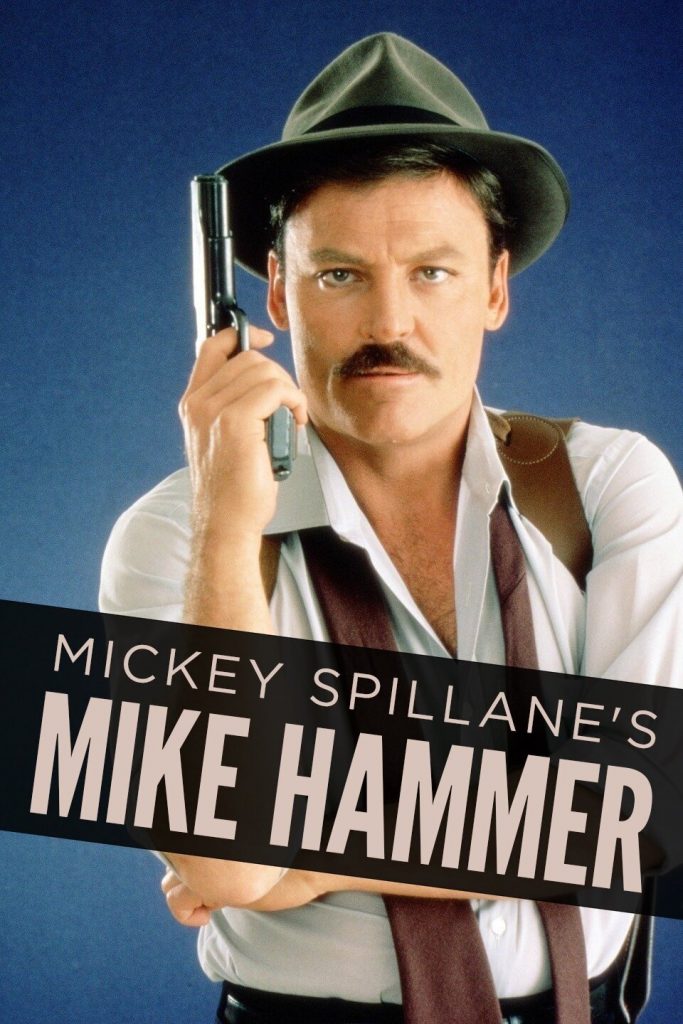

There were two successful television series based on Mike Hammer, the first in the late 1950s and the second, 1984-87, starring Stacy Keach in a semi-noir, 1950s setting, with Spillane’s sex and violence carefully bleached out.

As an author of pulp, Spillane’s guiding principle was that “violence will outsell sex every time”, but combined they will outsell everything. As part of the promotion for his novels he adopted a Hammeresque persona, which was transparently an act. He once told a British interviewer, “I always say never hit a woman when you can kick her.” When asked, “Is that the treatment you give Mrs Spillane?”, he primly replied, “We’re talking about fiction.”

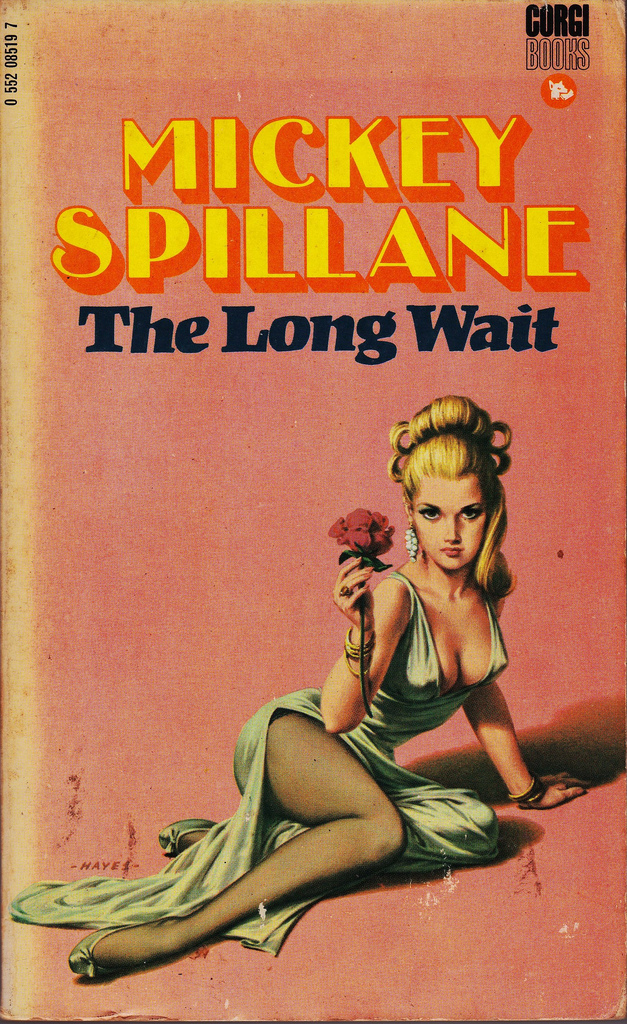

There were three Mrs Spillanes. With the first, Mary Ann Pearce, whom he married in 1945, he had two sons and two daughters. Then, in 1964, he divorced her and married Sherri Malinou, a model 24 years his junior, who had caught his eye when she featured on the cover of one of his books. He called the agency and asked them to send over the blonde with the beautiful butt: “they sent her over, and I never sent her back.” He used her (nude) on the cover of The Erection Set (1972).

But the marriage broke up and, in 1983, he married Jane Rodgers Johnson; he had two stepchildren, Britt and Lisa. From 1954 he lived with his successive families at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, where he sailed, fished and resolutely did not play golf. He always dressed in black and white; as in the novels, he liked to keep things simple.

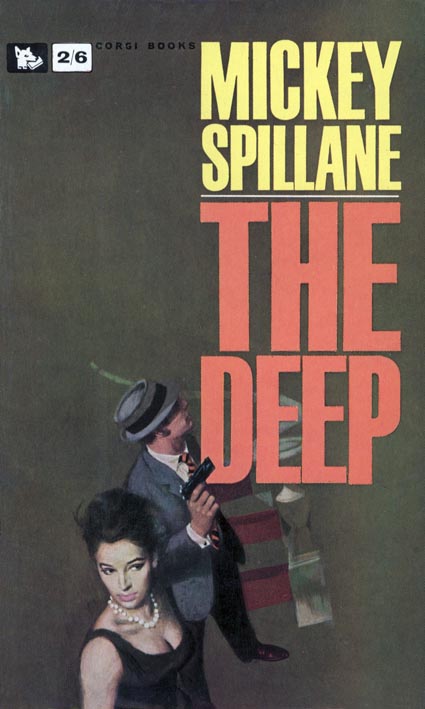

There were two long gaps in Spillane’s career. The first followed his conversion to the Jehovah’s Witnesses in 1952, which led to a 10-year hiatus in novel writing (although he was earning substantially from subsidiary rights over this period). He returned to form in 1961 with what is reckoned to be the best of the Hammer novels, The Deep.

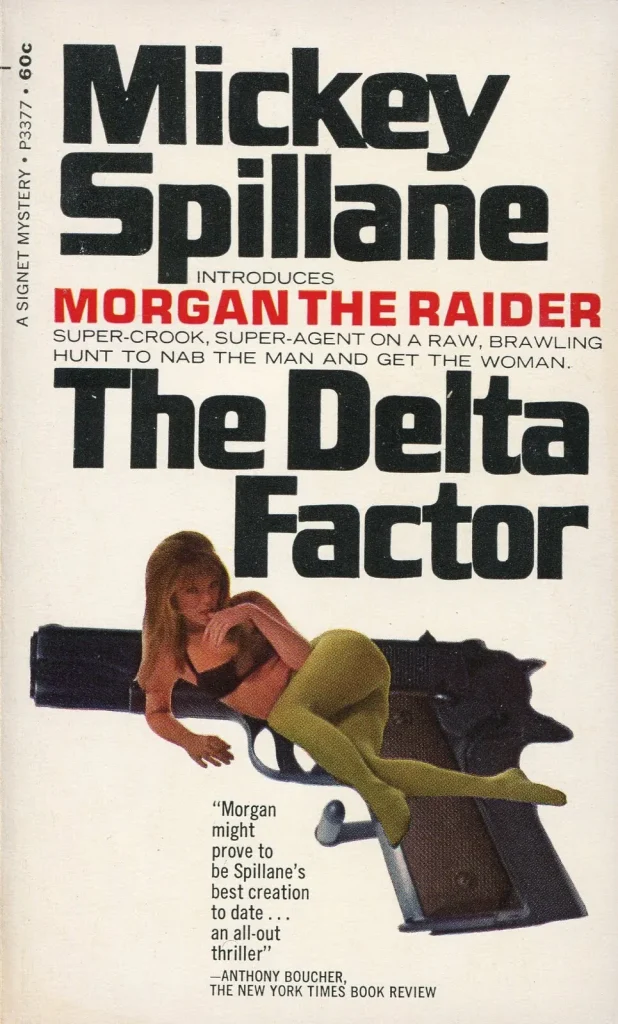

From then until 1972 the novels came out with the old facility, and Spillane created a new series hero for the decade, Tiger Mann – launched with Day of the Guns (1964). Mann is a “secret agent” and witnesses to Spillane’s sense that his thunder had been stolen by James Bond. He claimed not to be worried by Ian Fleming – “he’s a gourmet” – but the reading public, fickle as ever, never returned in their once record-breaking droves. The non-series books, The Erection Set and The Last Cop Out (1973), were heavily hyped but comparative failures, as were the second-generation Hammer books, The Twisted Thing (1966), The Body Lovers (1967) and Survival Zero (1970). Post-Lady Chatterley and post-Last Exit to Brooklyn, Spillane had lost the power to shock.

There was another gap, between 1973 and 1989, during which Spillane again wrote no full-length fiction, though he did try his hand (as a dare with his publisher) at two, well-received children’s books, The Day the Sea Rolled Back (1979) and The Ship That Never Was (1982). During this period he was famous to the American television-watching public for his appearance in Miller Lite beer commercials (though he was reported not to be a heavy drinker).

By the time he returned to Hammer fiction with The Killing Man (1989), Spillane was in his 70s, as were what remained of his faithful readers. A suspicious number of reprints of the early novels were in large-type; the Guardian reviewer of The Killing Man (1990) was kind but dismissive.

Spillane hammered on with Black Alley (1996), although by now his bolt was clearly shot. He reportedly suffered a stroke in his later years. Over the last decades (to his disgust, one suspects) he received increasing critical respect for his contributions to the idiom of crime fiction, and for having played a pioneer’s role in the postwar paperback revolution. His wife and children survive him.

· Frank Morrison ‘Mickey’ Spillane, writer, born March 9 1918; died July 17 2006

Topics