Eric Porter obituary in “The Independent” in 1995.

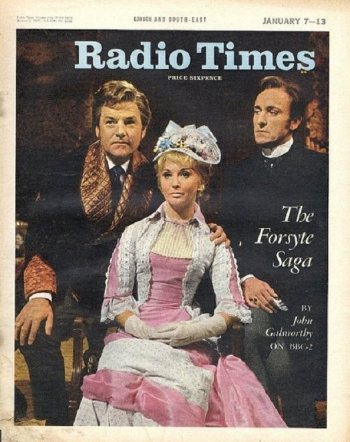

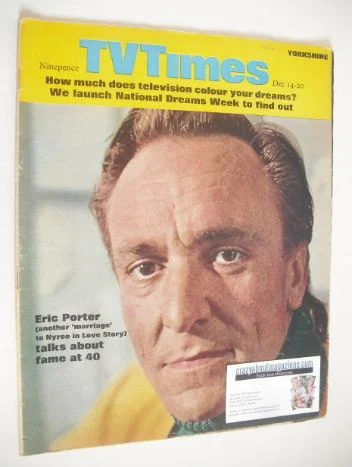

When television producers were casting demons and po-faced characters in the Sixties and Seventies, Eric Porter seemed to be on all their shortlists, becoming a star as Soames Forsyte in The Forsyte Saga in 1967, after more than 20 years in acting.

The role of the brutal lawyer in John Galsworthy’s story of a family of London merchants at the turn of the century catapulted Porter to world- wide fame – and infamy. “They buttonholed me in Detroit, in Malta and on a Spanish beach”, Porter once said. “There was no hiding place. Even in Budapest this large lady with dyed hair came beaming over, placed a plump hand on my chest and said, “Aaaach, Soooames Forsyte”.

Porter was born in London in 1928, the son of a bus conductor. His parents wanted him to qualify as an electrical engineer, so he went to Wimbledon Technical College at the age of 15 and, a year later, started work for the Marconi Telegraph and Wireless Company, solderingjoints. But he had acted in school plays, and was soon trying to get into the theatre.

Although Porter failed to get a scholarship to RADA, a district schools drama organiser obtained an interview for him with Robert Atkins, director of the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre company at Stratford-upon-Avon, which later became the Royal Shakespeare Company. He was signed up, in 1945, aged 17, and made his stage debut carrying a spear, at £3 a week. He then joined Lewis Casson’s theatre company in a revival of Saint Joan, making his London debut in 1946 at the King’s Theatre, Hammersmith (now the Lyric), as Dunois’s page.

After nine months’ National Service as an engine mechanic in the RAF, Porter toured with Sir Donald Wolfit, acted in repertory theatre in Birmingham, Bristol and at the London Old Vic, and appeared in Sir John Gielgud’s Hammersmith season and in the West End.

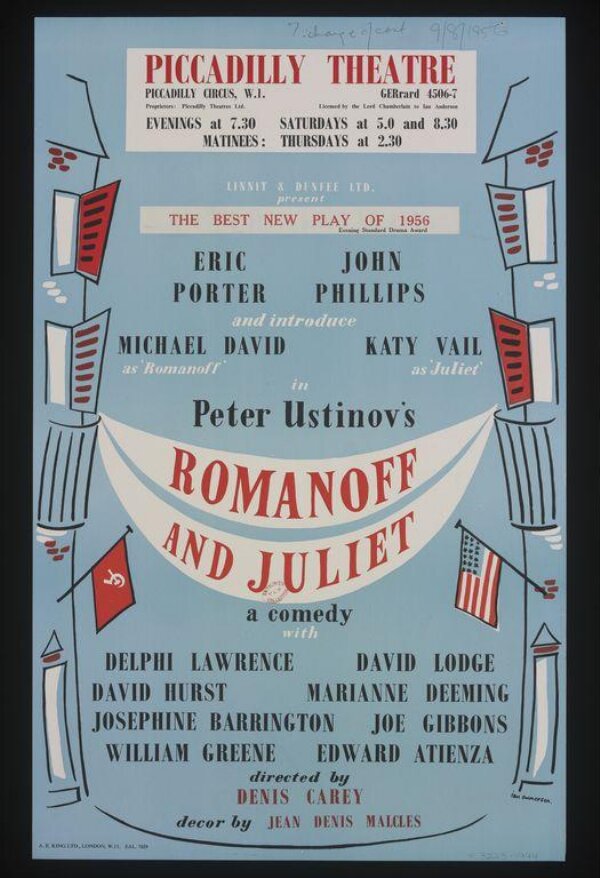

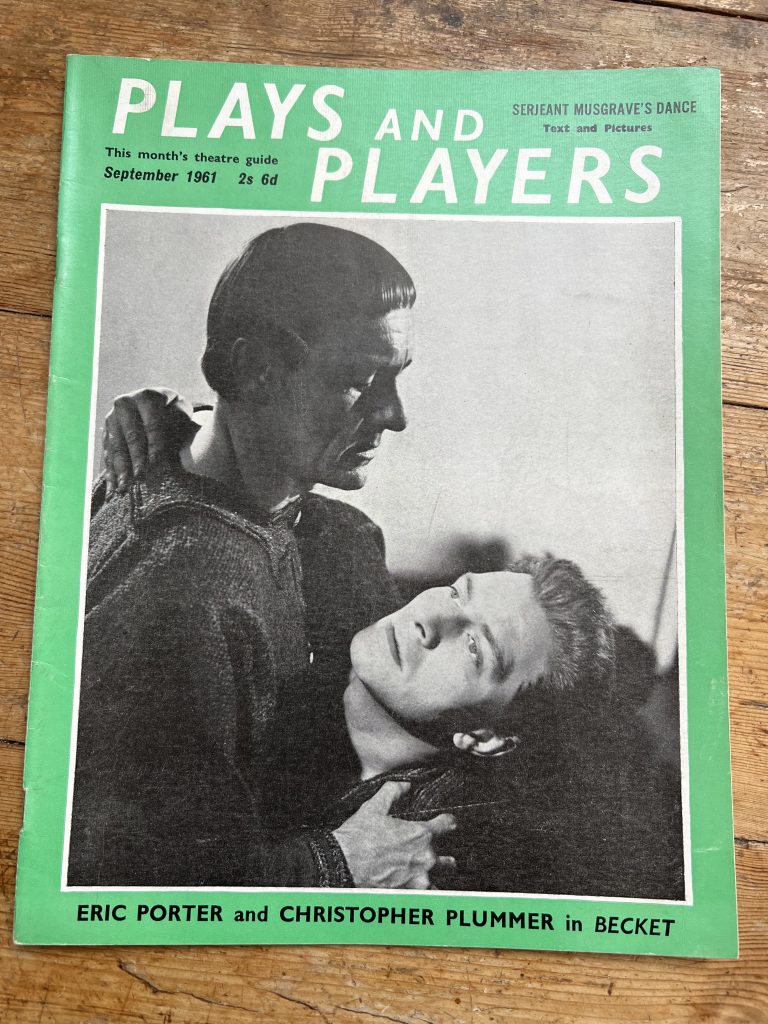

He made his first Broadway appearance as the Burgomaster in The Visit at the opening of the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre and, back in Britain, played Rosmer in Rosmersholm at the Royal Court Theatre, which won him the London Evening Standard Drama Award as Best Actor in 1959.

Porter’s television career began with The Physicist and he later appeared in The Wars of the Roses (1965), before fame came with the part of the brutal Soames Forsyte, in 1967. The Forsyte Saga, adapted from John Galsworthy’s novel, was an instant hit, featuring Porter as a monster who is incredibly cruel to his first wife, Irene (played by Nyree Dawn Porter), but who became loved by female viewers throughout the world. However, the scene where Soames rapes Irene shocked everyone – including the cast and crew. ”I tugged and pulled at her bodice,” Porter recalled, ”and to everyone’s horror, there was blood all over the place. I had gashed my hand on a brooch she was wearing.”

His role in the 26-part series, screened initially on BBC2 but repeated on BBC1 the following year, and enjoying another two repeat runs, won him Best Actor awards from Bafta and the Guild of Television Producers and Directors. The programme would have become a long-term best-seller for the BBC, but suffered from being the last important television drama series to be made in black and white.

Having made his name, Porter took the title roles in television productions of Cyrano de Bergerac (1968) and Macbeth, appeared in The Winslow Boy, Man and Superman – opposite Maggie Smith – Julius Caesar and Separate Tables. He and Nyree Dawn Porter played man and wife one more time in an episode of Love Story called “Spilt Champagne”. Ten years after The Forsyte Saga made waves, Porter teamed up again with its producer, Donald Wilson, and reprised his viciousness in a BBC adaptation of Anna Karenina, in which he played the dull government official Karenin, who throws his pregnant wife Anna (Nicola Pagett) across the bedroom into a chair.

His subsequent television roles included Neville Chamberlain in Winston Churchill: The Wilderness Years (1981), a po-faced deputy governor in The Crucible, an ageing playwright in A Shilling Life, Moriarty in The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Fagin in Oliver Twist. He also played the elderly, silver-haired Russian aristocrat Count Bronowsky in the 1984 blockbuster series The Jewel in the Crown as well as appearing more lightheartedly in The Morecambe and Wise Show. Porter’s last small-screen appearance was as Player in a new production of Dennis Potter’s Message for Posterity. It was completed earlier this year.

Anthony Hayward

Eric Porter was one of those actors often thought to be on the brink of greatness, rather than actually great at any time, writes Peter Cotes.

He was always compelling in whatever he tackled, and could claim at one time to be one of the most versatile players in Britain who seriously made each role he enacted true. Few tricksy tactics were resorted to; the actor was there to serve the play.

In the 1950s, he emerged as an actor to be watched and capable when young of playing middle-aged and even old men without resorting to the heavy make-up, that look and smell of glue, and the obligatory facial greasepaint lining that can look artificial and at times absurd.

Porter enjoyed playing classical roles in the theatre best of all and was unusually happy, in a way that few other actors were, when touring with Sir Donald Wolfit. He found both the Birmingham Rep and Bristol Old Vic much to his liking and the regular audiences attending those playhouses admired this highly dependable actor who was capable of making small roles big without ever stepping out of line and “hogging the limelight”. His Bolingbroke to Paul Scofield’s Richard II in 1952 at the Lyric, Hammersmith, was a case in point – he repeated the character in Henry IV at the Old Vic three years later. Before that time he had done more than his fair share of touring since making his debut in 1945. Seasons with the Travelling Repertory Theatre Company took him to the King’s Theatre, Hammersmith, before he did National Service with the RAF (1946-47).

After stints with the extrovert Wolfit, travelling the “sticks” in the Forties, and the shy introvert Barry Jackson at Birmingham, learning about “attack” from the former and “taste” from the latter, Porter found himself in Hammersmith again playing Jones at a moment’s notice in Galsworthy’s The Silver Box at the Lyric Theatre there. He caught the critical eye and there was no looking back.

Chekhov followed at the Aldwych, in the West End, when he made an arresting Solyoni in The Three Sisters in the early Fifties. He joined Gielgud’s Company in a “season” and I saw him at the Lyric Hammersmith as Bolingbroke,in February 1953, followed by such costume pieces as The Way of the World and Venice Preserv’d, both in the same season, before he returned to play leading roles. He was accorded leading-man status at the Bristol Old Vic, where he made an impressive Becket in Murder in the Cathedral and Father Browne in The Living Room, before returning to the Old Vic, in London, playing featured roles.

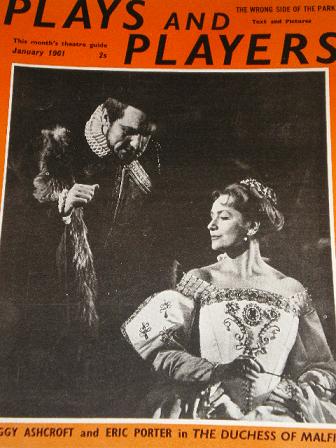

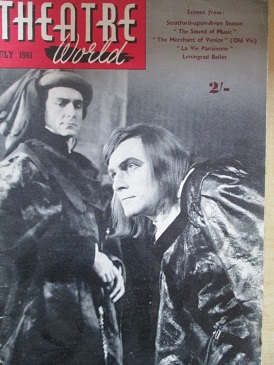

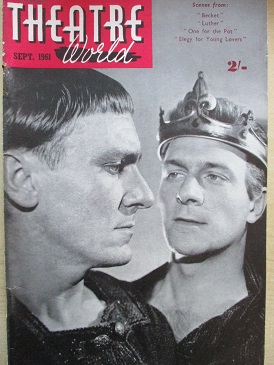

Since the 1960s he had been one of the leading players at the RSC, for whom his characters had included an outstanding Antonio in The Duchess of Malfi, a striking Barabas in The Jew of Malta, and such “friendly villains” as Shylock and Macbeth as well as a majestic Lear (on Wolfit lines caught from watching that grand Lear play the role). And a Captain Hook in Peter Pan in the 1970s not only of “Eton and Balliol” but as Barrie’s play demands “of green-light melodrama” also.

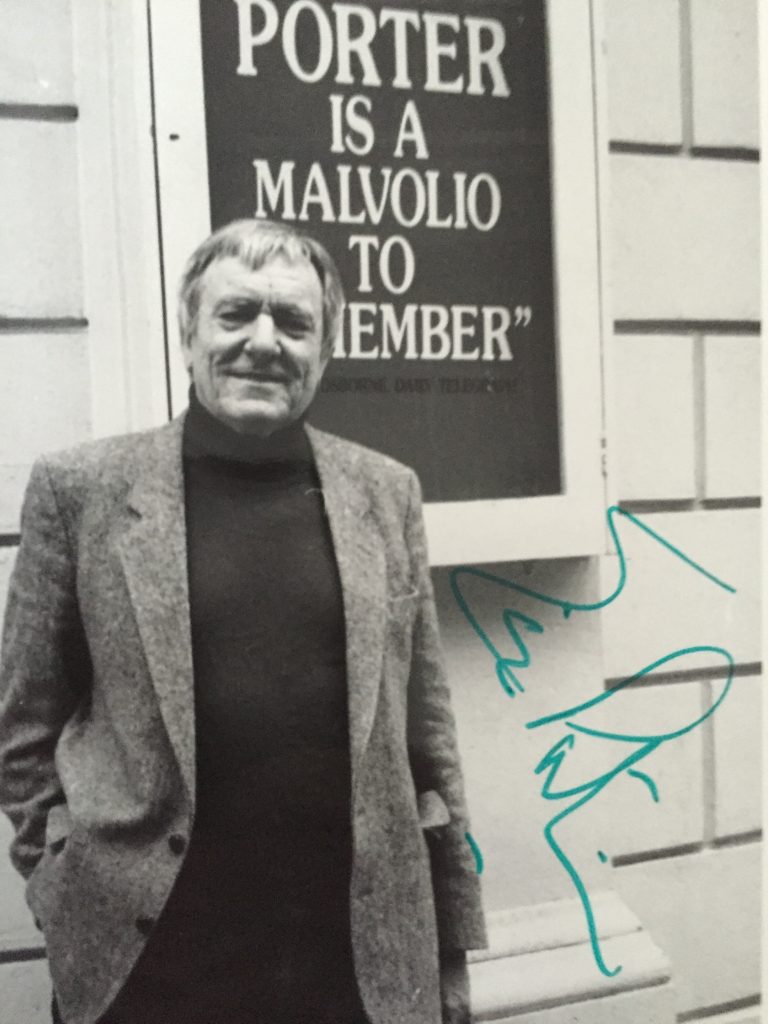

After such a succession of hits, Porter was hardly ever away from plum parts in England, and made appearances on Broadwaybefore returning to London for his award-winning Rosmer in 1959. Although now recognised as a star by his fellow actors, he found that the world-wide stardom associated so often with the playing the great parts eluded him, despite a Malvolio of wit and pathos and a Leontes in The Winter’s Tale of depth and poignancy at Stratford.

Porter injected more into the theatre than he ever took out of it considering the parts he so finely portrayed and the dignity he gave to the roles he embellished with his out-of-the- ordinary talent – mostly in the theatre classics which he loved best but also in such “moderns” on television as Separate Tables.

Porter used to say he was “lucky” in his parts and accepted philosophically the fact that many a lesser actor than himself caught the stardom which is often accorded to the ordinary rather than the great.

But who can doubt that Eric Porter had more than a modicum of greatness in his talent?

Eric Porter will always be part of television history for his performance in The Forsyte Saga, in 1967. But his work in films was also more than appreciable, writes Tom Vallance.

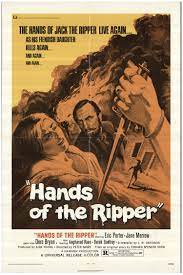

Though his cinema work included classic roles familiar from his stage career, he is best remembered for two Hammer films, The Lost Continent (1968) – adapted from Dennis Wheatley’s Uncharted Seas, in which he was top billed as the captain whose tramp steamer wanders into an unknown civilisation – and Peter Sasdy’s Hands of the Ripper (1971), in which he co-starred with Angharad Rees as a doctor using Freudian theories to try to cure the murderous daughter of Jack the Ripper.

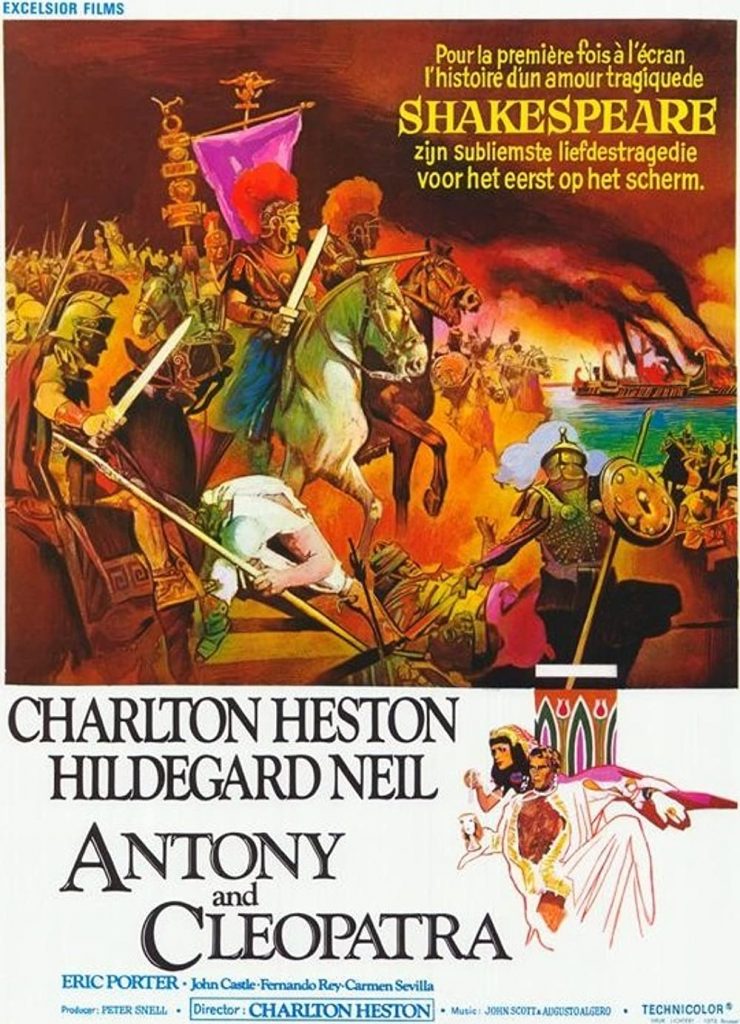

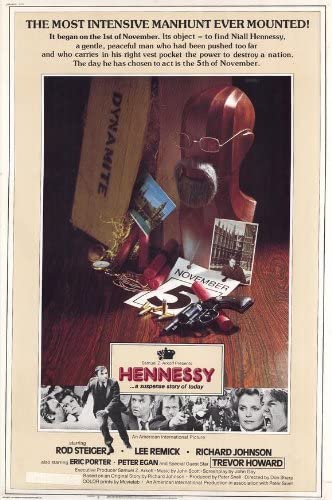

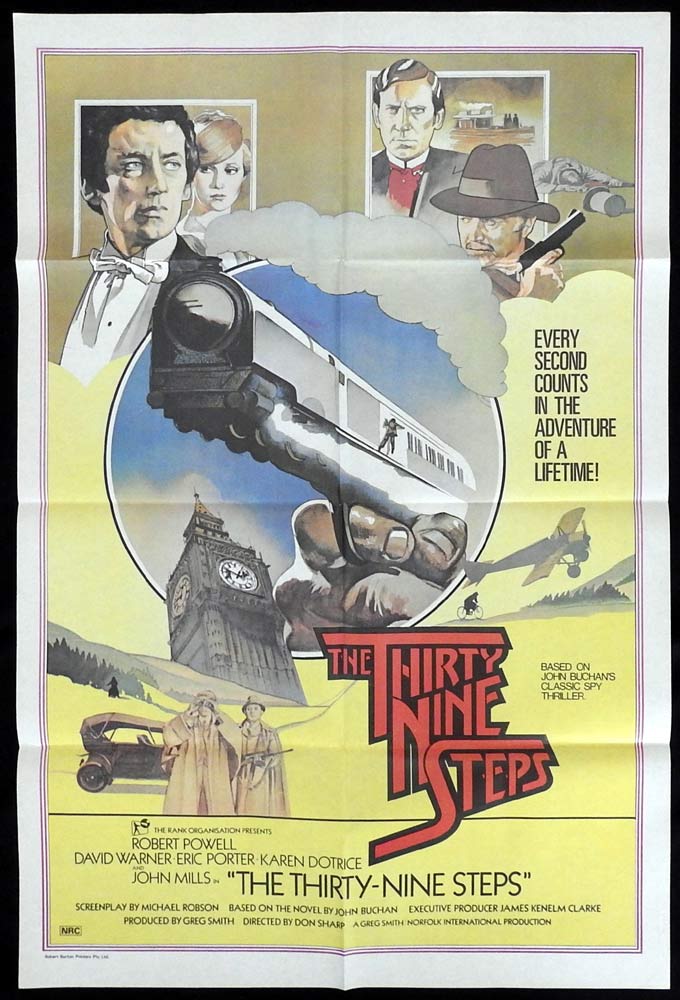

His authoritarian demeanour led to his frequent casting as military men or aristocracy in such films as Charlton Heston’s ponderous Antony and Cleopatra (1973 – he was Enobarbus), Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), The Heroes of Telemark (1965) and Nicholas and Alexandra (1971). In Fred Zinnemann’s gripping thriller The Day of the Jackal (1973), Porter is the fanatical head of a secret military organisation who believes General de Gaulle has betrayed France by giving Algeria independence, and hires a professional killer to assassinate him. It was not a large role but a pivotal one to which Porter brought typically chilling conviction.

Eric Porter, actor: born London 8 April 1928; died London 15 May 1995.