Frank Finlay obituary in “The Guardian” in 2016.

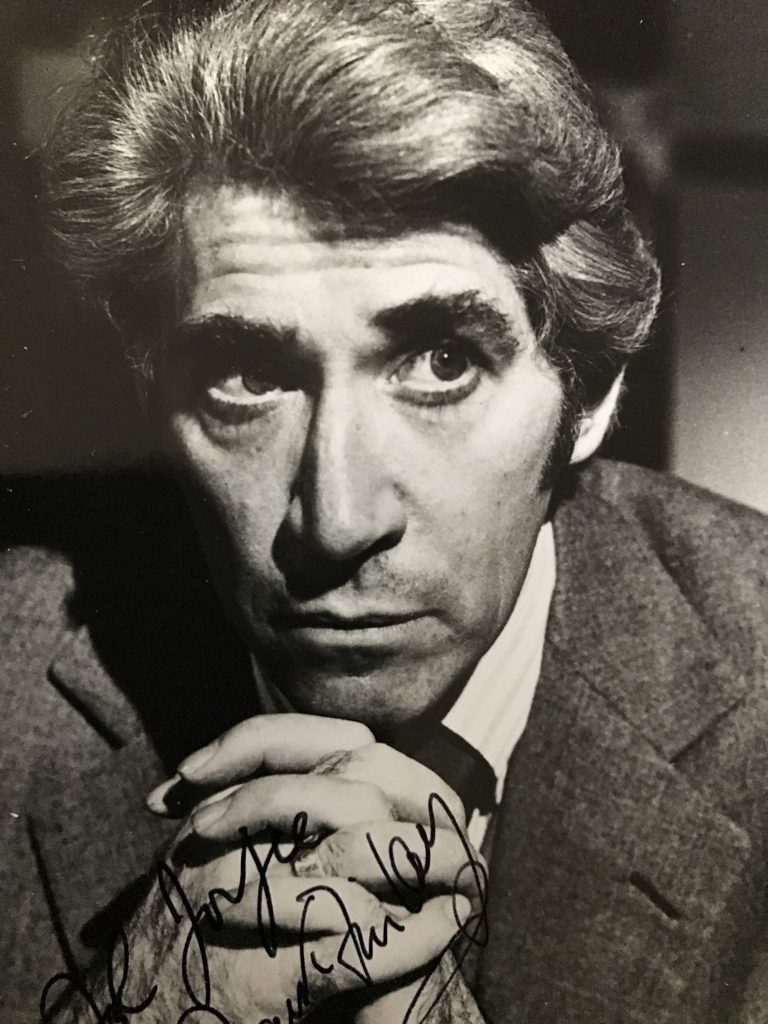

As an actor, there was something sinister and sepulchral about Frank Finlay, who has died aged 89. He was able to imply depths of feeling by doing very little. And his distinctive voice had an in-built echo, so that he sounded as though he was speaking inside a dark, dank cave.

Although he was a devout Catholic, he rarely played good people. His luxuriant mane of black hair (turning grey and, later, white) complemented a skull-like appearance with still, sunken eyes and prominent cheekbones. On television he played Jean Valjean in a BBC mini-series of Les Miserables, Adolf Hitler, Casanova and, most famously, an incestuously obsessive father in Andrea Newman’s television drama, Bouquet of Barbed Wire. The latter series, produced by London Weekend Television in 1976, starring Susan Penhaligon as his daughter, Sheila Allen as his wife and James Aubrey as his American teacher son-in-law, made Finlay a household name after years of toil.

He was closely involved in the early days of two major theatrical enterprises of the last century, the English Stage Company at the Royal Court, and the National Theatre. At the Court he forged an enduring friendship and stage collaboration with Joan Plowright in the Wesker Trilogy, and then joined Plowright’s husband, Laurence Olivier, in the new National Theatre at Chichester and the Old Vic.

Together with Plowright and other Royal Court personnel – the actors Robert Stephens and Colin Blakely, the directors John Dexter and William Gaskill – he represented a key creative surge in Olivier’s project. He played the Gravedigger in the opening NT production of Hamlet (starring Peter O’Toole) at the Old Vic in 1963, followed by a string of leading roles, notably Iago to Olivier’s Othello.

Olivier, who had been talked into playing Othello by his literary manager, Kenneth Tynan, said that he did not want “a witty, Machiavellian Iago. I want a solid, honest-to-God NCO.” He got that to such an extent that Finlay, at that time an inexperienced Shakespearean, veered between dull and shaky in one of the longest roles in the canon (after Hamlet). But he improved immeasurably over the play’s run: with his director, Dexter, he had decided that Iago had been impotent for years; hence his loathing for the pantherine sexuality of the general who had done him out of a job, and his brutally callous alienation from Joyce Redman’s Emilia. The resulting film, directed by Stuart Burge, showed him at his best – phlegmatic, malignant and manipulative – and he, Olivier, Redman and Maggie Smith as Desdemona all received Oscar nominations.

In some ways Finlay was difficult to fathom as an actor. When he was cast as Lopakhin in an all-star production of The Cherry Orchard at the Haymarket theatre in London in 1983, the director Lindsay Anderson was flummoxed in rehearsals by his impassive visage, wondering in his diaries if he was “closed” or merely stupid. But the performance, in the end, was superb. Finlay’s acting was not spine-tingling, but he was highly effective and always, in his own surly way, imposing.

Like many myopic actors, he often moved around the stage with his eyes wide open, “like a silly-looking fish,” said Stephens: “So he got contact lenses, and when he walked on the stage and saw the audience, he nearly died of fright. He never wore them again.”Advertisement

Born in Farnworth, near Bolton, in Lancashire, Frank was the son of Maggie (nee Griffin) and Josiah, a butcher, whose families had relocated from Ireland in the 19th century to work in the mills. Frank was educated at Bolton technical college and worked as a butcher’s apprentice and grocer’s assistant before making his debut in fortnightly rep at Troon, Ayrshire, in 1951, followed by seasons of 10 months each in Halifax and Sunderland.

In 1953 he won a scholarship to Rada in London. He had met Doreen Shepherd when they were both members of the Farnworth Little theatre, and they married in 1954, living mostly in Shepperton, Middlesex. His career subsequently gathered pace in repertory seasons in Bolton, Guildford and on tour with an Edinburgh festival production of Rosemary Anne Sisson’s The Queen and the Welshman. In 1958, at the Belgrade, Coventry, he portrayed old, incontinent Harry Khan – he usually played above his own age – in Arnold Wesker’s Chicken Soup With Barley, the first of the trilogy (followed by Roots and I’m Talking About Jerusalem) that soon after made his name, and Wesker’s, at the Royal Court.

He also appeared at the Court in Serjeant Musgrave’s Dance (1959) and The Happy Haven (1960), both by John Arden, and opposite Rex Harrison in Chekhov’s Platonov and as Corporal Hill in Wesker’s Chips With Everything (1962). Tynan said that this “beautifully observed” parade ground martinet, a prole by birth, went over to the enemy whose orders he carried out with a wry and humourless gusto.

As the National got going at Chichester, he scored again in Arden’s The Workhouse Donkey (1963), as a blustering Labour politician, Alderman Butterthwaite, another northern character part executed with a high degree of absurd and demonic rascality. He developed a lugubrious strain as both the Gravedigger and then as Willie Mossop in Harold Brighouse’s Hobson’s Choice, the bootmaker raised to new heights by Plowright’s doughty, rebellious Maggie.

After Iago, other notable roles that cemented his reputation at the Old Vic in 1965 were as Giles Corey in Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, a gloriously officious and sour-faced Dogberry in Franco Zeffirelli’s Sicilian production of Much Ado About Nothing, and the Cook in Brecht’s Mother Courage (directed by Gaskill). The following year, also at the Old Vic, he played a stooge-like Joxer Daly to Blakely’s Captain Boyle in Sean O’Casey’s Juno and the Paycock, making himself look surprisingly thin in a huge greatcoat.

Having featured as Jesus Christ in Dennis Potter’s Son of Man at the Leicester theatre and the Roundhouse in 1969, he briefly joined the Royal Shakespeare Company to play the Marxist theatre critic Bernard Link, visiting the post-1968 European hot spots on a lecture tour, in David Mercer’s After Haggerty (1971).

Potter’s play had initially been seen on television, where Finlay himself now became increasingly visible: first, in the title role of Potter’s Casanova (1971), a six-part BBC series, in which Finlay’s unusual lothario specialised in guilty postcoital tristesse over his dependency on women; then as a squinting, foxy Shylock in a big bushy beard opposite Maggie Smith’s Portia in a 1972 production of The Merchant of Venice, as the Führer in The Death of Adolf Hitler in the same year, and as Sancho Panza to Harrison’s fantastical Don Quixote in 1973.

Back on the stage, he was an alcoholic trade unionist in Trevor Griffiths’s The Party (1973), a scabrously critical look at the British left, in which Olivier made his NT farewell as a Glaswegian Trotskyite.

In the same year the two actors had appeared together (Olivier executing some scene-stealing business with a hat), and with Plowright, in a glorious version by Keith Waterhouse and Willis Hall of Eduardo De Filippo’s Saturday, Sunday, Monday, which transferred in 1974 to the Queen’s theatre, London. Convinced of his wife’s infidelity, Finlay’s Peppino sat sulking downstage, heart-broken. Michael Billington suggested that he had adopted the Italian playwright’s own acting technique, “providing a still centre in a whirlpool of activity: dapper, grave and trim like a middle-class Buster Keaton, his very quietness made his eventual eruption of emotion seem like a thunderbolt from the heavens”.

National Theatre service was completed with a twinkle-toed burglar, Freddy Malone, all teeth, spats and two-toned hair, in Michael Blakemore’s fizzing revival of Ben Travers’s Plunder in 1976. In the same year he played a film director, Ben Prosser, in John Osborne’s self-immolating Watch It Come Down, and the ghost of a Czech communist cabinet member, Josef Frank, in Howard Brenton’s Weapons of Happiness, superbly directed by David Hare, the first commissioned play in the new National on the South Bank. Finlay’s Frank struck up a telling rapport with Julie Covington’s communist agitator, and their scenes together were an electrifying fusion of experience and innocence.

Finlay’s film career, allied to his stage credentials, kept him solidly in work thereafter. Early on, he had appeared in two Michael Winner movies, both comic romps, in 1967: The Jokers and I’ll Never Forget What’s’isname. He played Porthos in the simultaneously filmed The Three Musketeers (1973) and The Four Musketeers (1974), both directed by Richard Lester. He cropped up in Richard Eyre’s The Ploughman’s Lunch (1983), scripted by Ian McEwan, and The Return of the Musketeers (1989), the least good of the trilogy, blighted by the death of Roy Kinnear in a riding accident on location.

Returning to De Filippo with Plowright, he had a great box office success in Filumena in the West End in 1978, touring with the production to Broadway, but he eclipsed even that highlight in his performance as a vampiric balletomane in James Saunders’s stage version of Ronald Harwood’s novel The Girl in Melanie Klein at the Watford Palace in 1980. This was a worthier enterprise than either his routine Captain Bligh in David Essex’s over-inflated musical Mutiny! at the Piccadilly in 1985 or his possibly murderous QC (the audience were sent out to consider their verdicts in the interval) in Beyond Reasonable Doubt, Jeffrey Archer’s glib potboiler at the Queen’s in 1987.

He then played two war criminals: in Michael Cristofer’s Black Angel at the King’s Head, London, in 1990, and in Harwood’s The Handyman at Chichester in 1996. His last stage appearance was as the old retainer Firs in The Cherry Orchard at Chichester in 2008. Harwood’s scripts for Roman Polanski’s The Pianist (2002) and Norman Jewison’s The Statement (2003), with Michael Caine, marked his last major movies, but he kept busy with much television work, including the role of Jane Tennison’s father in the last two series of Prime Suspect in 2006 and 2007.

In 2008 he appeared as Anorah, keeper of the unicorns, in the BBC drama series Merlin. He was appointed CBE in 1984 and received an honorary doctorate from the University of Bolton in 2010.

With Doreen he had three children, Stephen, Cathy and Daniel. Stephen died in 2004, and Doreen in 2005. He is survived by Cathy, Daniel, four granddaughters and two grandsons.

• Frank Finlay, actor, born 6 August 1926; died 30 January 2016