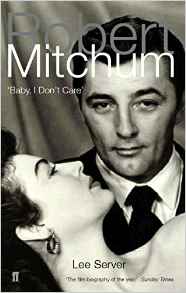

Robert Mitchum obituary in “The Independent” in 1997.

If films were exclusively about acting, the American cinema would be the greatest in the world; but they aren’t, and it isn’t.

Yet, even as one rages against the imbecility of so much of Hollywood’s current output, one cannot but be stupefied by the easy, natural virtuosity, at times an almost imperceptible virtuosity, of American movie actors, especially when they confine themselves to the register of unfussy, vernacular naturalism with which they are most at ease. (If called upon to extend their range, the same actors can be deeply embarrassing to watch – think of the implausible endeavours of such fine performers as Willem Dafoe, Harvey Keitel, Barbara Hershey and Harry Dean Stanton to impersonate characters from the Bible in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ.)

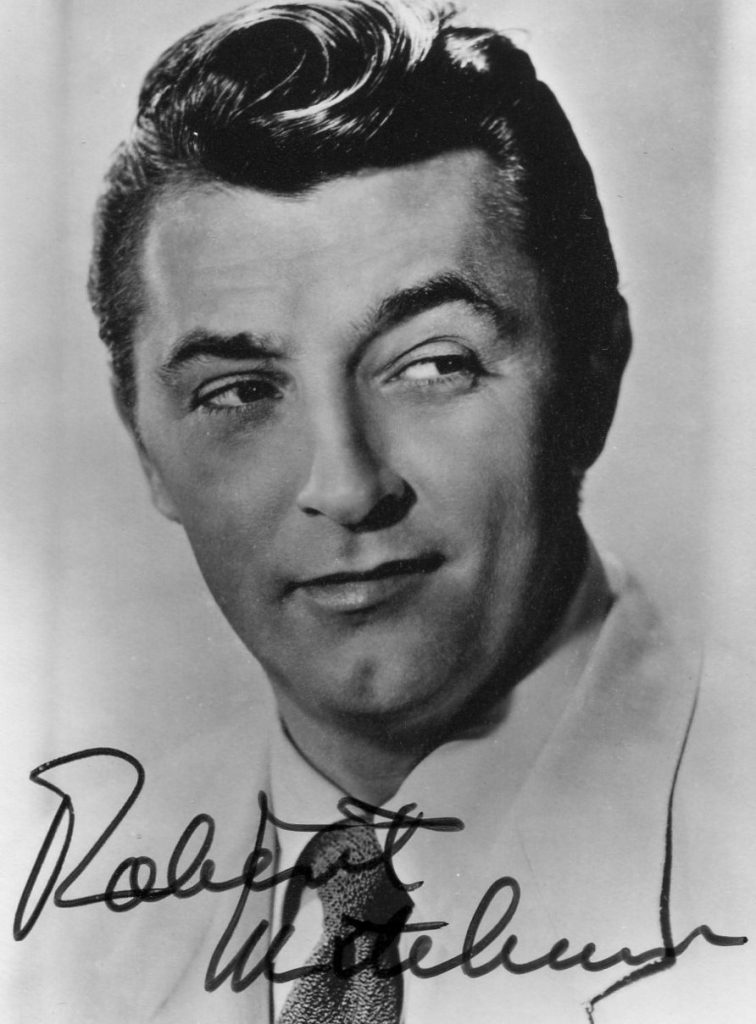

Robert Mitchum was one of the greatest of all Hollywood actors – a paradoxical claim if one elected to listen to the man himself. “It sure beats working,” he would remark of his chosen vocation with a laconically shrugged shoulder of self- disparagement. Or else, when honoured with a retrospective of his films by the 1989 Deauville Festival at the conclusion of a long and richly varied career, “Got the same attitude I had when I started. Haven’t changed anything but my underwear. I’ve played everything except midgets and women

“People can’t make up their minds whether I’m the greatest actor in the world – or the worst. Matter of fact, neither can I. It’s been said I underplay so much, I could have stayed home. But I must be good at my job. Or they wouldn’t haul me around the world at these prices.”

It’s true that Mitchum’s performances tended to resemble each other; the crucial point is that they did not resemble anyone else’s. He was a massive figure of a man, generous of shoulder and hip, and so could scarcely be more unlike those wiry young actors whose jittery mannerisms predominate in the contemporary cinema. He seemed to amble dozily through his performances, a cigarillo dangling from one corner of his mouth, his lazy, slow-motion drawl from the other, in such a way as practically to negate the whole concept of a “performance”. In that stumblebum languor, however, lay precisely his strength as an actor.

Mitchum realised (or instinctively knew) that the screen inflates and stylises, and that a single raised eyebrow is therefore all that is needed to carry an expressive charge.

Interestingly, too, despite his boozy, parodically macho public image, much promoted in the publicity that surrounded him, as one of Hollywood’s “hell-raisers” (in 1948 he was convicted for possession of marijuana, served a brief prison sentence and, more bleary-eyed than ever, made the cover of Confidential magazine), he would find himself outfoxed by a series of scheming women in the films noirs of the Forties, films of silence and violence, of shadowy urban anxieties that, like the individuals beset by them, appeared to have no fixed abode. He fell victim to Jane Greer in Don Siegel’s The Big Steal (1949), Faith Domergue in John Farrow’s Where Danger Lives (1950), Jane Russell in Farrow’s His Kind of Woman (1951) and a deceptively demure Jean Simmons, both sphinxy and minxy, in Otto Preminger’s Angel Face (1953).

There was a curious quality of sincerity, of what one might call “authenticity”, in Mitchum’s persona on screen that may have derived from his own feckless adolescence. Left fatherless in his infancy, he “lit out for the country” in genuine Huck Finn style and drifted from one truly odd job to another, working variously as an engine wiper on a freighter, a night-club bouncer, a ditch-digger and a publicist for an astrologer.

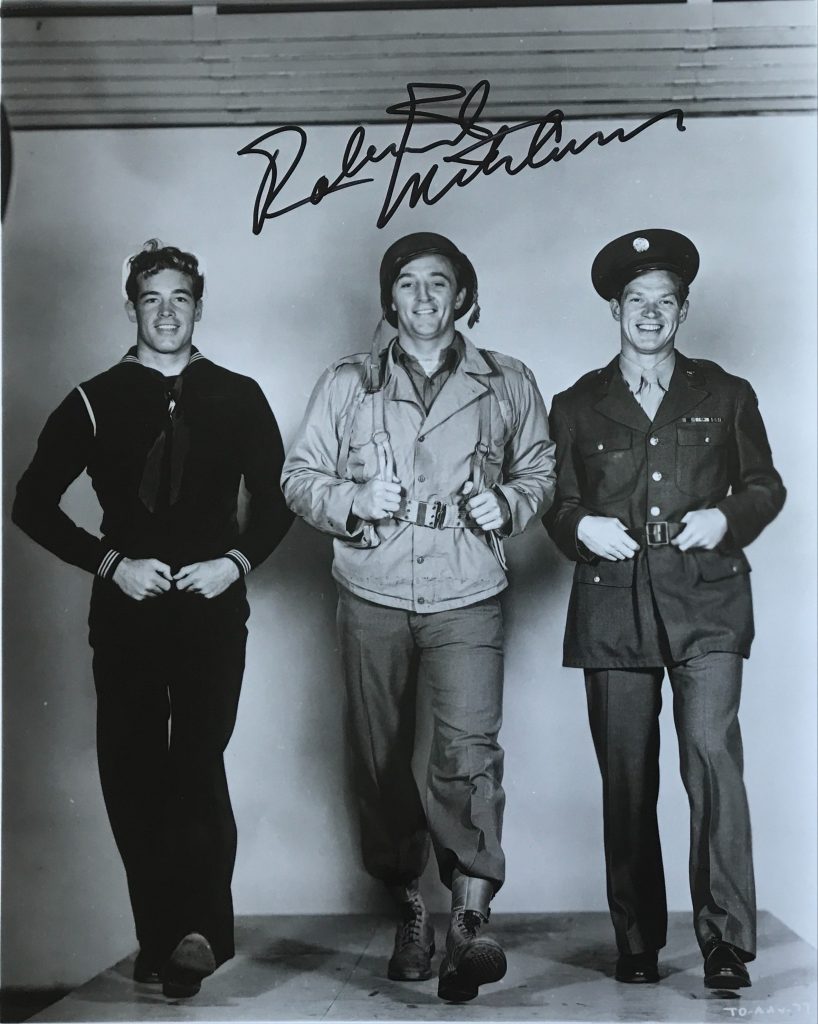

It was in 1940, when he was 23, that he finally settled down. He married his childhood sweetheart, fathered a son (Jim, who was subsequently to become an actor himself) and accepted a nine-to-five job at the Lockheed aircraft factory in California. Then, as an amateur actor at the Long Beach Theater Guild, he was spotted by a talent scout and launched his Hollywood career in 1943 – an auspicious year for him, quantitatively if not qualitatively, as he made appearances in no fewer than 18 films, many of them Hopalong Cassidy westerns.

In 1944 he appeared in the first of his films that is still remembered, Mervyn LeRoy’s Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, and in the following year, for his performance as a young soldier in William Wellman’s The Story of GI Joe, he was nominated for his only Academy Award.

Thereafter, his laid-back but somehow not unmannered personality meant that he would be cast indiscriminately in every major genre. He starred in melodramas: Vincente Minnelli’s Undercurrent and John Brahm’s The Locket (both 1946), Josef von Sternberg’s Macao (1952), Stanley Kramer’s Not as a Stranger (1955), and Minnelli’s Home From the Hill (1960). In thrillers: Edward Dmytryk’s Crossfire, on the theme of anti-Semitism, Jacques Tourneur’s superb snowbound film noir, Out of the Past (both 1947), and J. Lee Thompson’s Cape Fear (1962), in which he was a particularly terrifying villain (he could also be seen, playing a different role altogether, in Martin Scorsese’s 1991 remake). In westerns: Raoul Walsh’s strange, intense Pursued (1947), Otto Preminger’s River of No Return (1954), in which he was teamed up with Marilyn Monroe, and Howard Hawks’s El Dorado (1967), a film as easygoing as he was himself. And, if more rarely, in comedies: John Huston’s Heaven Knows, Mr Allison (1957), in which he was a tough, barrel-chested marine stranded on a desert island with a nun played by Deborah Kerr, and Stanley Donen’s The Grass Is Greener (1960), a stiflingly “smart”, buttoned-up comedy of manners into which his presence brought not so much a breath as a draught of fresh air.

As was usually the case with stars of his generation, the Seventies and Eighties offered much less fertile ground for his gifts. He seemed to be endlessly popping up as much-decorated generals in lengthy, spectacular, tedious reconstructions of notable turning points in the Second World War (The Longest Day, Anzio, Midway, etc).

A pity, too, that it was only then – when, both in a generic context and in terms of his own age, it was already too late – that someone thought to cast him as Philip Marlowe in two very dissimilar remakes of earlier Raymond Chandler classics: Dick Richards’s unexpectedly convincing Farewell, My Lovely (1975); and, three years later, Michael Winner’s characteristically thick-ear adaptation of The Big Sleep (which ought to have been called “The Big Yawn”).

The best for last, though – not only his own finest performance but unquestionably the finest film in which he ever appeared, Charles Laughton’s masterpiece The Night of the Hunter. Made in 1955, a total failure in critical and commercial terms, and in consequence the only film Laughton was ever permitted to direct, it featured Mitchum as a psychopathic preacher in lyrically nightmarish pursuit of two infants who are watched over by a vigilant, feisty fairy godmother played by Lillian Gish.

With the words LOVE and HATE tattooed on his knuckles, he first befriends them and then, as it were, befiends them, eager to let his itchy fingers get their hands around their little necks. In this unique film Robert Mitchum was the very personification of the Bogey Man.

Some of Robert Mitchum’s most memorable work can be found within the genre of film noir, writes Tom Vallance. In the post-war Hollywood of the Forties, the period in which Mitchum emerged as a top star, the genre was flourishing, and his laconic, sleepy-eyed passivity lent the requisite air of cynical disillusionment and weariness to characters whose innate romanticism makes them ready victims.

In each of the two masterpieces of film noir in which he starred for RKO, Out of the Past and Angel Face, Mitchum is bewitched by a duplicitous female but, unlike noir heroes played by Humphrey Bogart, Alan Ladd and Dick Powell, he is not able to abandon them to their punishment but is instead destroyed by them.

Jacques Tourneur’s Out of the Past (in Britain it took the title of the Geoffrey Homes book on which it is based, Build My Gallows High) is a stylish essay in corruption in which Mitchum, as the trenchcoated private investigator Jeff Bailey, is hired to find the former girlfriend (Jane Greer) of a gangster (Kirk Douglas), who tells him she also stole $40,000. Mitchum tracks Greer down in Mexico where, after an idyllic romance against moonlit backdrops of a raging seashore, a sudden rainstorm and billowing fishing nets hauntingly captured by the richly textured low-key lighting of Nicholas Musuraca (who had defined RKO’s noir style since 1940 with baroque set-ups and inspired chiaroscuro), he accepts her story that Douglas lied about the money and settles down with her.

When she later kills dispassionately, Mitchum realises his mistake and leaves her, but cannot escape the past and is eventually drawn back into a web of blackmail, deceit and murder. “You’re like a leaf,” he finally tells Greer, “that blows from one gutter to another.”

With a terrific script by Homes (using his real name, Daniel Mainwaring) described as “the best dialogue heard west of Chandler and the most alluringly diabolical characters south of Hammett”, Tourneur created a true masterwork, dominated by Mitchum’s persuasive portrayal of a basically good man who ultimately realises that his only escape from the woman who has obsessed him lies in their mutual destruction. “Bob would walk through anything he didn’t like,” said Greer, “but if he liked the part and the director, he’d be brilliant. I think he’s brilliant in Out of the Past.”

Mitchum’s character in Otto Preminger’s Angel Face is superficially more innocent than Jeff Bailey – he is an ambulance driver, not a private eye. But, when called to attend a wealthy woman, he quickly succumbs to the charms of her beautiful stepdaughter (Jean Simmons), breaks with his fiancee, and accepts a job as family chauffeur. Even when he realises that Simmons plans to murder her stepmother, he is unable to break away.

Preminger’s direction brings out intriguing ambiguities in his plot and characters, with his trademark eye for perverse psychology, while Mitchum, in what could easily have been a bland portrayal of a naive working-class man easily seduced by a beautiful heiress (allowing the film to be merely a vehicle for the superb Simmons), presents a complex mixture of rationality and honesty compromised by a fatal obsession.

“Bob always seemed disinterested when it came to rehearsing and scriptreading,” said Jane Greer. “But when the director called `Action’, he knew exactly what he was doing. He hit all the right marks and delivered a great performance.”

Robert Charles Duran Mitchum, actor: born Bridgeport, Connecticut 6 August 1917; married 1940 Dorothy Spence (two sons, one daughter); died Montecito, California 1 July 1997.