Telly Savalas obituary in “The Guardian” in 1994.

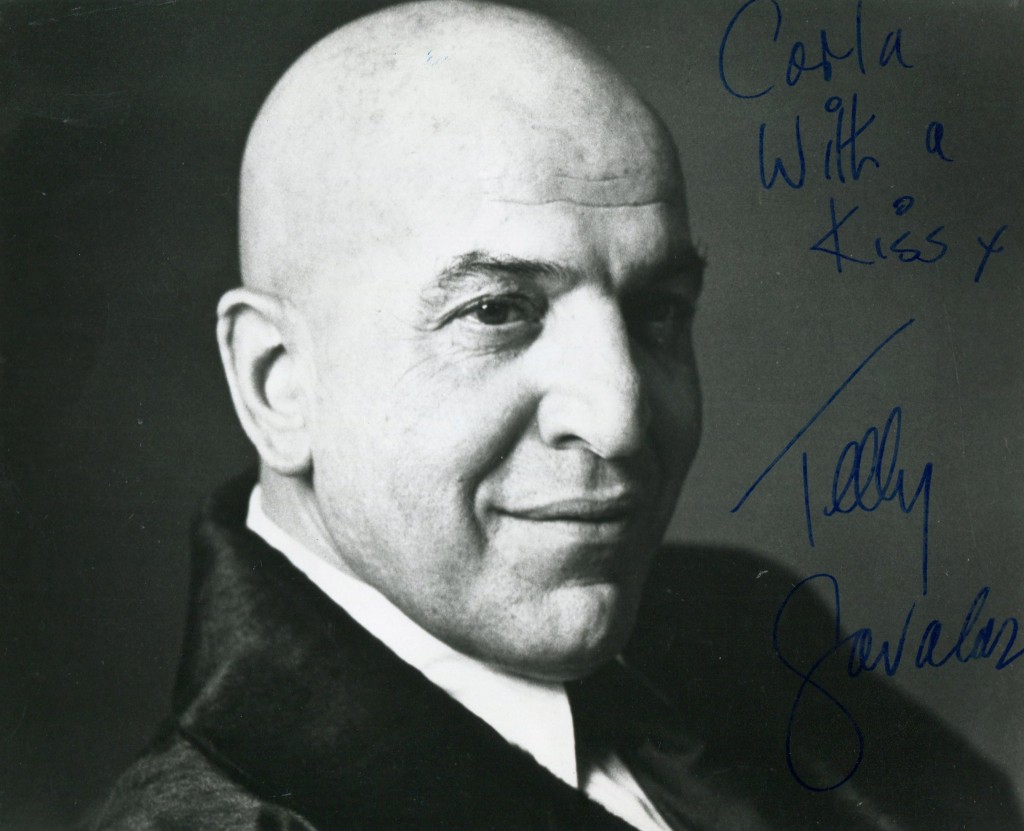

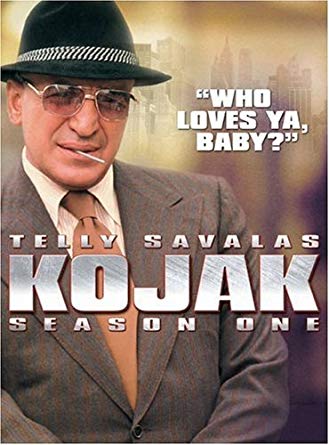

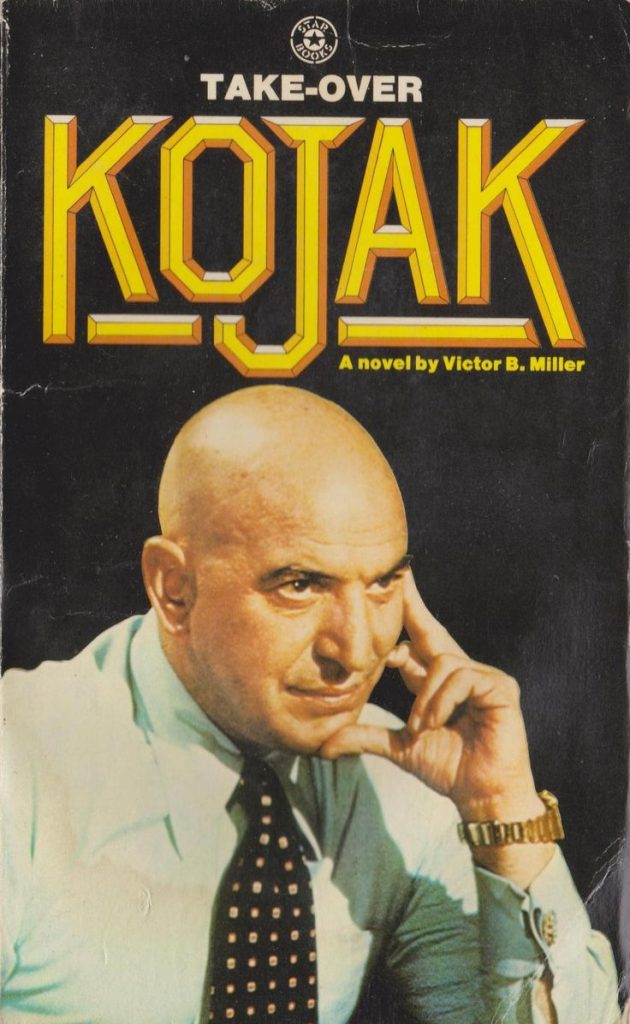

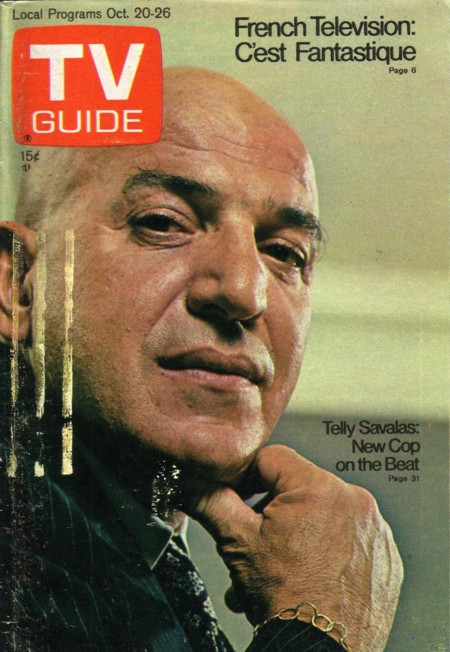

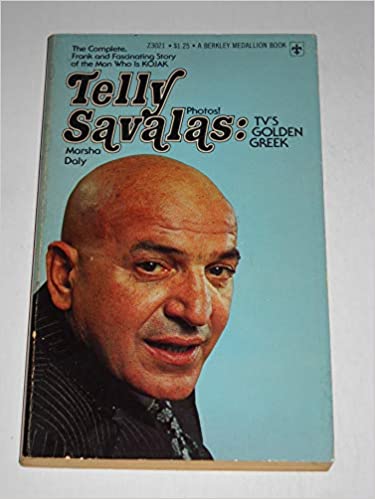

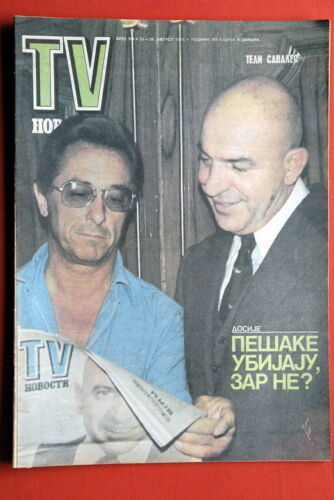

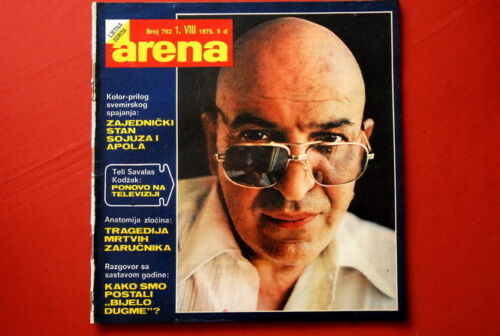

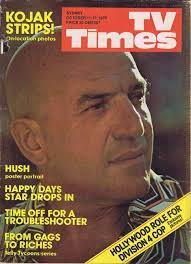

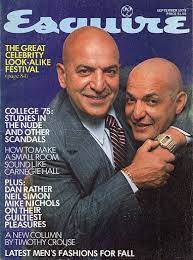

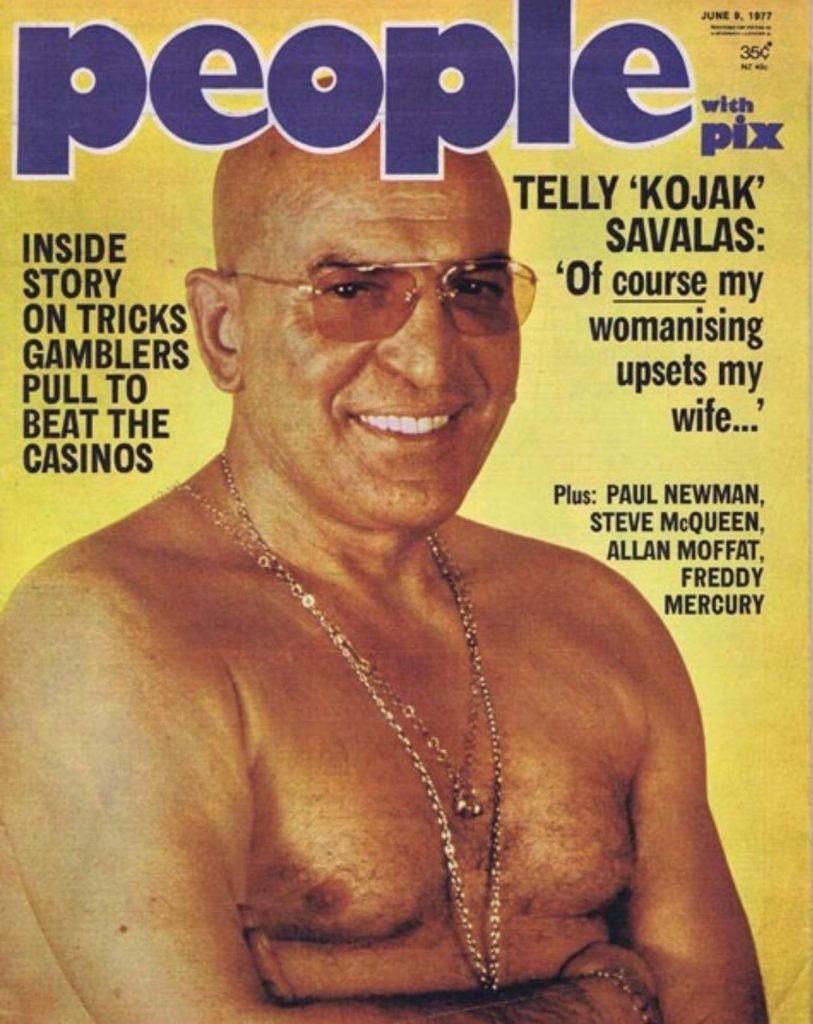

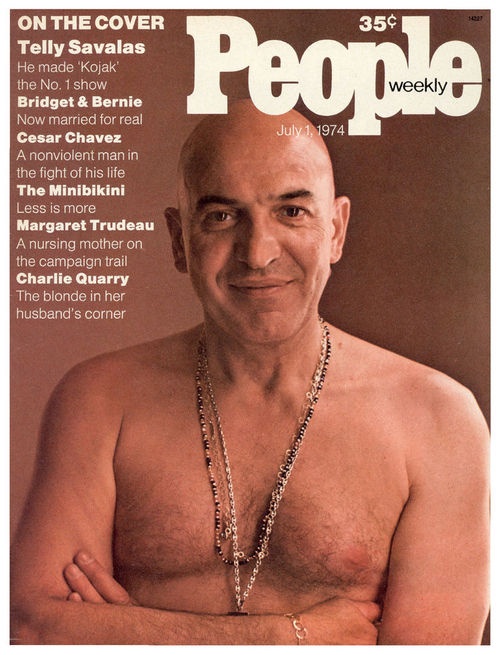

In 1973 a television cop series transformed a much-respected movie actor of the second rank – in box-office terms – into a figure instantly recognisable the world over. Telly Savalas was Lieutenant Theo Kojak of the New York Police Department, bald, not ugly but no oil painting (‘Romeo inside a gorilla exterior’, he once described himself), with intense eyes and a bewitching smile – when he cared to use it.

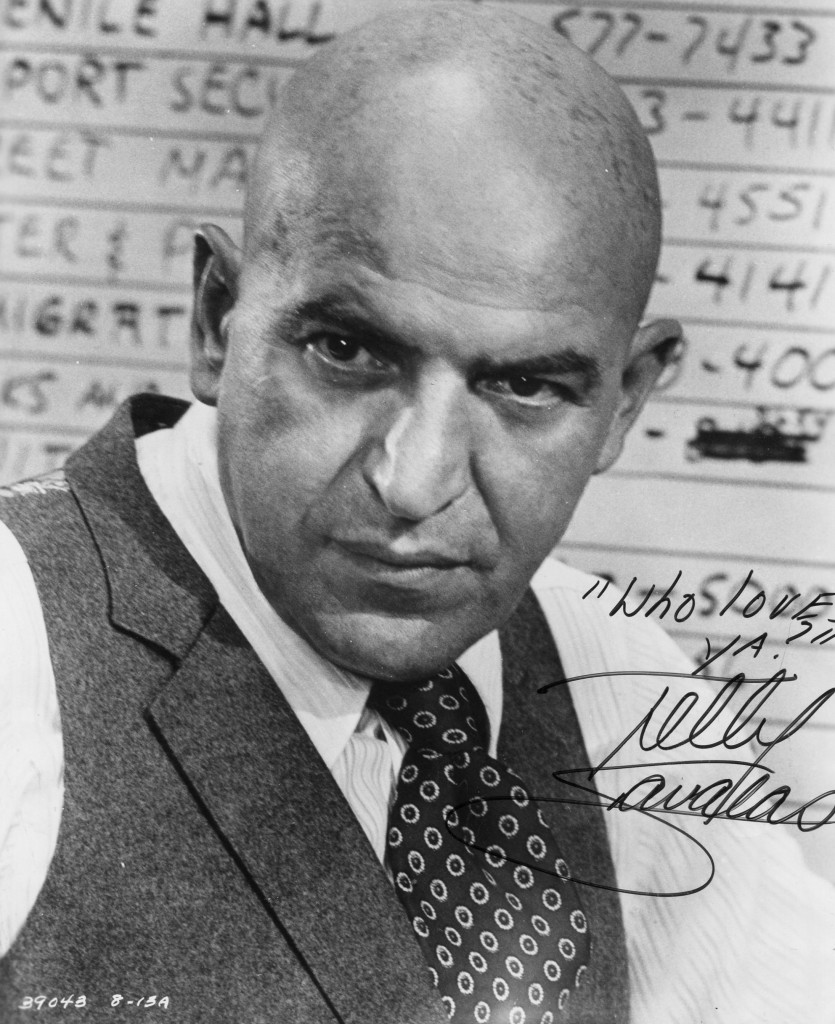

Kojak preferred to appear menacing to his enemies and even to his colleagues. In speech he was direct, never wasting words, though these tended to be sarcastic. All the most popular television series, from The Untouchables to Cheers, have something special to them: in Kojak, more than the casual, near- rebellious, atmosphere of the precinct (new to television but not to movies) it was Kojak’s character and Savalas’s dynamic playing of him. He sucked on lollipops, sported glaring fancy waistcoats and porkpie hats, and demanded ‘Who loves ya, baby?

Kojak was sympathetic to outcasts and ruthless with social predators. The show maintained a high quality to the end, mixing tension with some laughs and always anxious to tackle civic issues, one of its raisons d’etre in the first place. It was required viewing in Britain every Saturday evening for eight years. To almost everyone everywhere Kojak means Savalas and vice versa, but to Savalas himself the series was merely an interval, albeit a long one, in a distinguished career.

A first-generation American of Greek extraction, he was born Aristotle Savalas in New York in 1924 and started his career in the Information Services of the State Department. He moved on to ABC television, in charge of Special Events and creating the prestigious Your Voice of America series. He had not acted or even considered doing so till he was asked if he could recommend an actor with a command of European accents. He decided to go to the audition himself, in 1959, and found himself appearing in Bring Home a Baby on Armstrong Circle Theater TV.

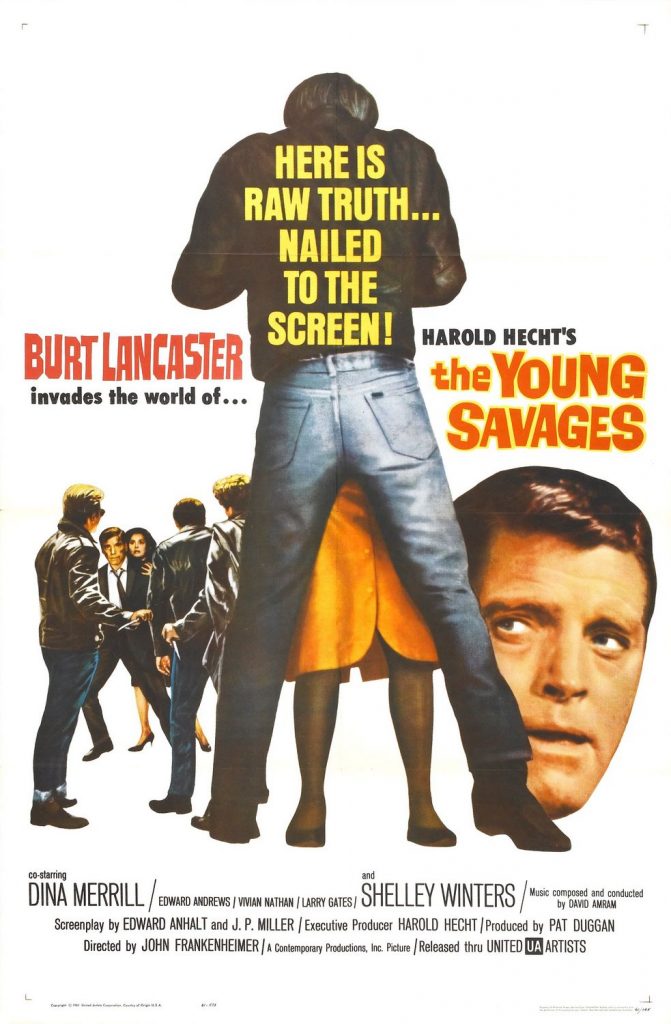

Further acting opportunities followed, and movies claimed him. He made his debut in a minor crime story, Mad Dog Coll (1961); but John Frankenheimer had already cast him in The Young Savages, which starred Burt Lancaster as a lawyer designated to prosecute some juvenile delinquents. It was not, as

social-concern films go, very profound; but for Savalas it was an omen, for he was the inspector in charge of the investigation. He was also the best thing in the film, as Frankenheimer recognised by putting him into Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), as a fellow-con of Lancaster’s; a performance which brought Savalas an Oscar nomination. In the interim, he had played another detective in Cape Fear, starring Gregory Peck and Robert Mitchum. The three films established Savalas as the sort of actor who could make mincemeat out of the likes of Lancaster and Peck.

The Man from the Diner’s Club (1963), with Danny Kaye, marked Savalas’s entry into screen comedies, which he managed with a confidence that enabled him to move from the most subtle expressions to the broadest of gestures. He played a morose mobster with tax problems. He was to demonstrate, when required, that he was simply one of the best screen heavies of his time. He was certainly one of the few whose reputation was unscathed by The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965), in which he played Pontius Pilate with obvious enjoyment. Its producer-director, George Stevens, persuaded Savalas to shave his hair for the role.

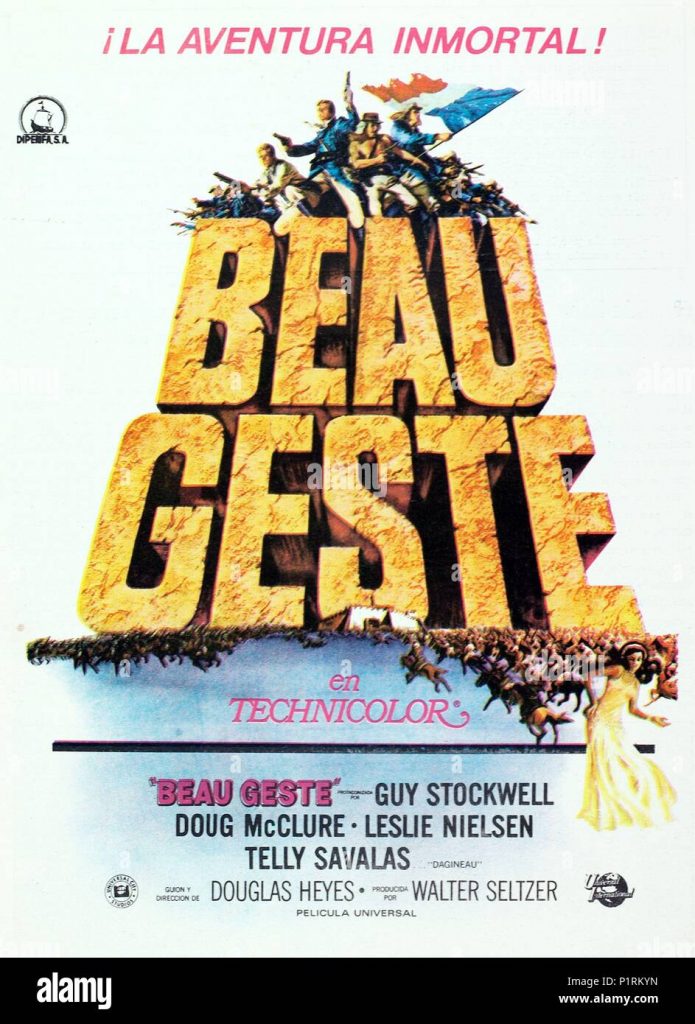

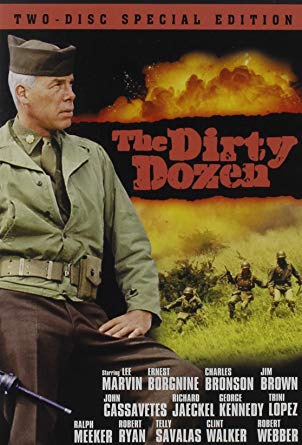

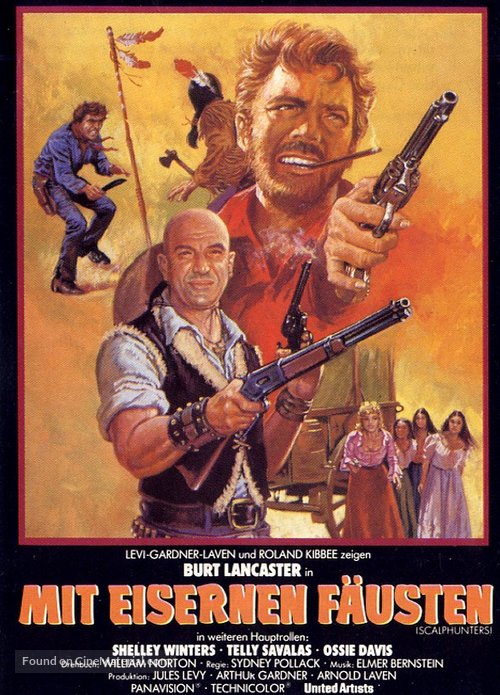

After playing the swinish Foreign Legion sergeant in Beau Geste (1966) – the only element to put it in the same class as the two earlier versions – he was the most unpleasant of Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen (1967) – soldier convicts promised remission after being sent secretly into France to prepare the locals for D-Day. As a religious maniac rapist, he stood out in a movie which included Lee Marvin and Charles Bronson also on top form; and the film’s popularity put stardom within Savalas’s grasp. He was superb as a psychopathic bounty-hunter who doublecrosses Burt Lancaster in Sydney Pollack’s irresistible western The Scalphunters (1968).

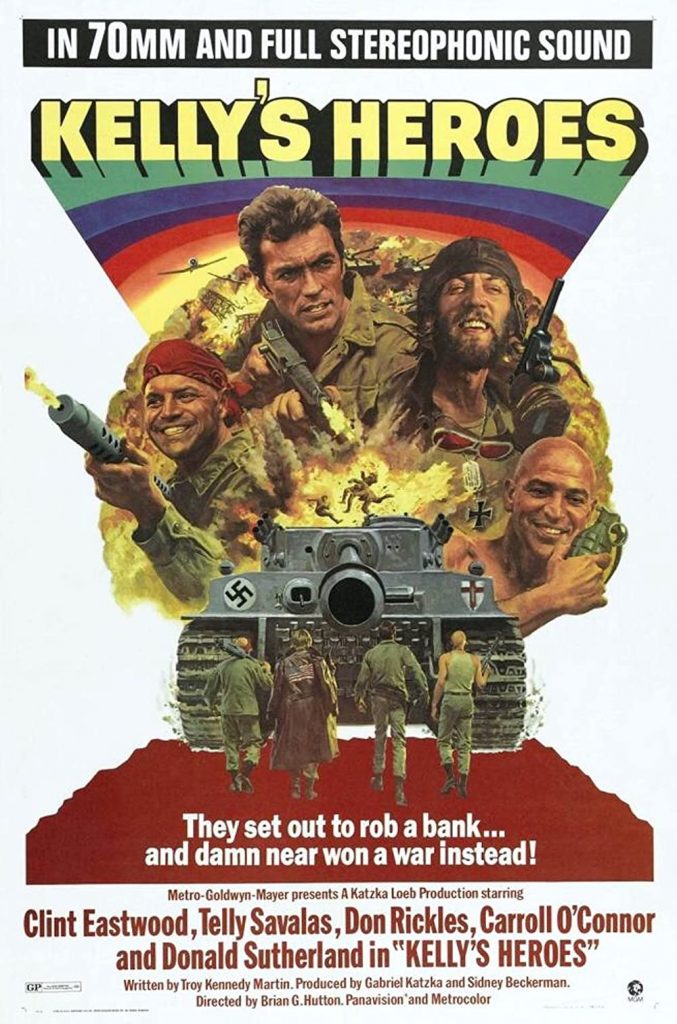

Melvin Frank’s Buona Sera Mrs Campbell (1968) brought Savalas back to Europe – literally, as one of the ex-GIs who, along with two others (Peter Lawford, Phil Silvers), was paying maintenance for Gina Lollobrigida’s daughter, conceived in Naples in 1944. He first acted in Britain in Basil Dearden’s black comedy The Assassination Bureau (1969), playing a newspaper magnate who commissions the would- be journalist Diana Rigg to expose a gang of professional killers. He remained in Britain, to be 007’s nemesis figure, Ernst Blofeld, the head of SPECTRE with dreams of world domination, in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Savalas was billed immediately after Clint Eastwood, overshadowing him however as an actor, in Kelly’s Heroes (1970), a wartime jape in which they and two others (Don Rickless, Donald Sutherland) steal behind German lines in pursuit of gold.

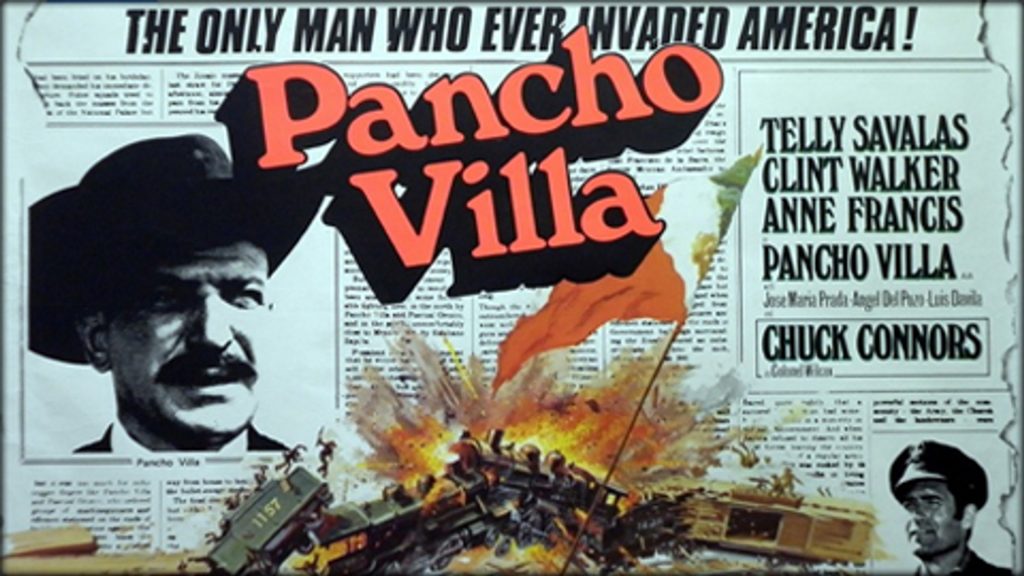

Savalas liked London. He took a house in the Boltons and enjoyed a romance with a Hollywood actress appearing on the London stage. He began to choose films for the locations rather than the roles, and thus did more than his fair share of spaghetti westerns, invariably as the villain. In the midst of these he was offered a television movie, The Marcus-Nelson Murders (1973), based on the Miranda case of 1963, when a detective was determined to see that a black teenager should not be convicted of a crime he did not commit. The direction and writing won Emmys for Joseph Sargent and Abby Mann respectively; Savalas was nominated and did not win but, more significantly, this was his introduction to Kojak: the three-hour film was in fact the pilot for a one-hour Kojak series.

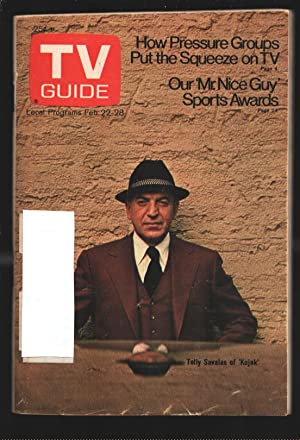

The decision to end Kojak after 110 episodes was mutual. The series had covered just about every crime that can happen in a large municipality and there were indications that the public was becoming somewhat less fond of the abrasive detective who hauled the wrongdoers into the precinct in the last 10 minutes. The novelty had worn off.

Savalas’s brother George played his shambling subordinate Stavros, and it was not till the end of the first run that it was revealed that they were brothers in the show as well. They returned to the roles in a telemovie for Universal, Kojak – the Belarus File (1985). This was to test the atmosphere for a new series, but nothing came of it immediately, nor of Hellinger’s Law, in which Savalas would have been a lawyer.

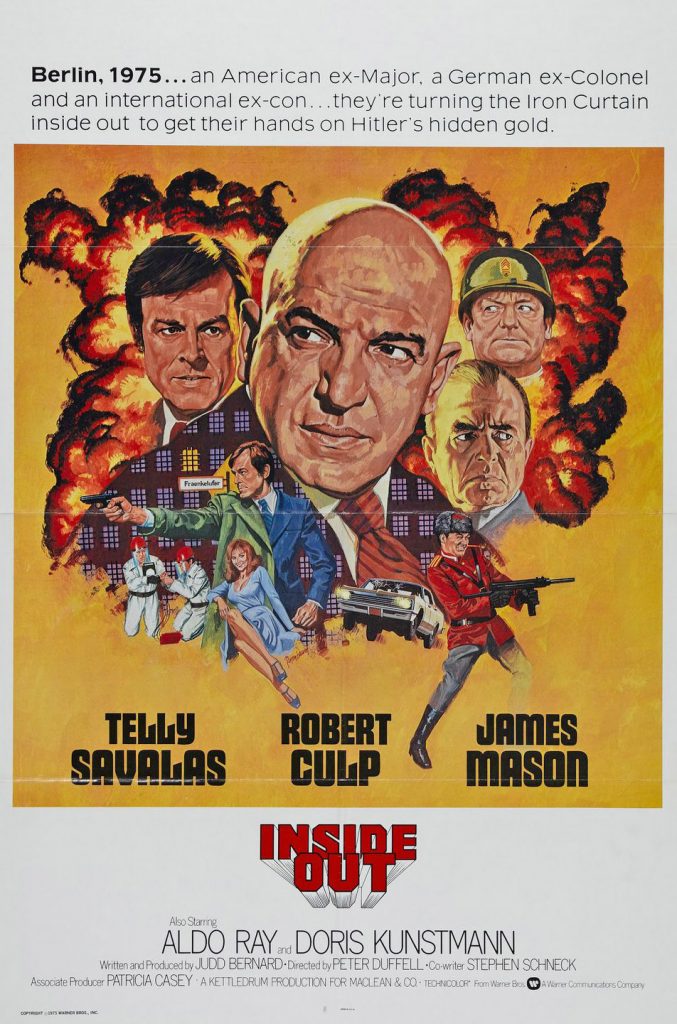

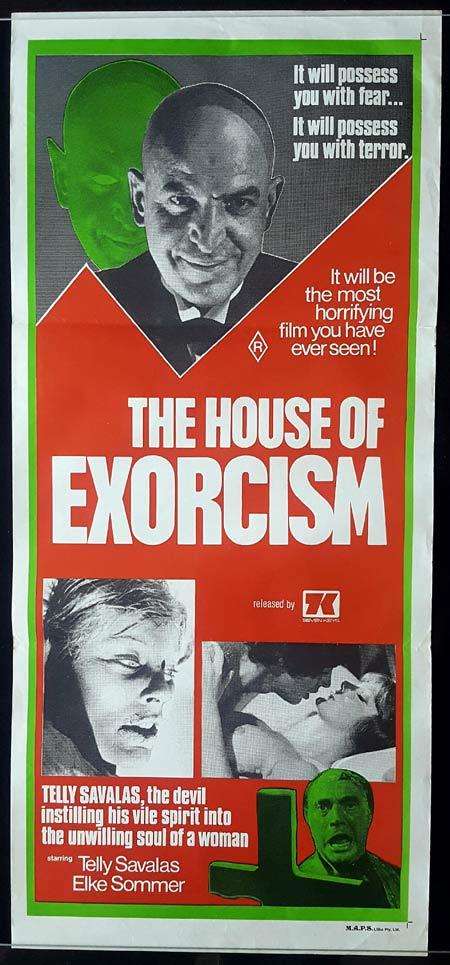

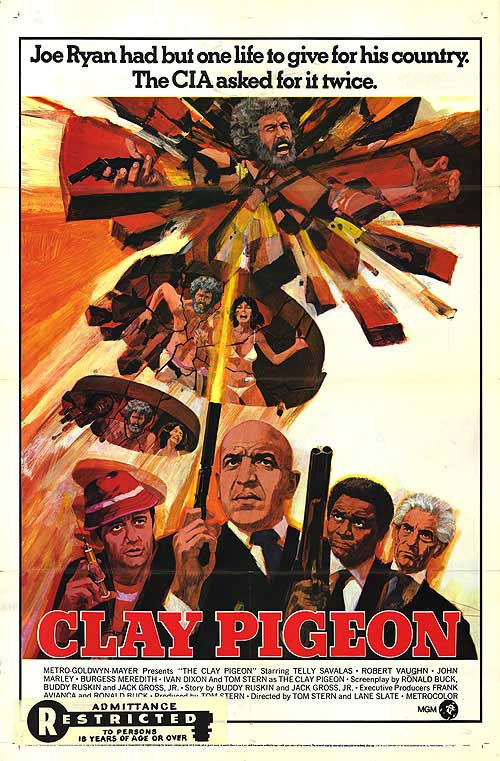

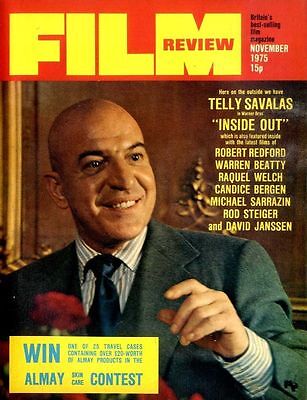

The initial impact of Kojak was to make Savalas more than ever in demand as a movie actor. Few of the films he now made were memorable, but mention should be made of the Anglo-German Inside Out (1975), since it became a feature of a libel-suit against the Daily Mail. That paper printed a story from the location-shooting in Berlin, alleging that Savalas’s ‘private excesses’ were damaging the film, and contrasting the professionalism of James Mason (described in reports as his ‘co-star’, though in fact billed below Savalas and in a smaller role). Mason not only testified for Savalas, but was in court for much of the hearing, beaming encouragement and seeing him awarded the then high sum of pounds 34,000.

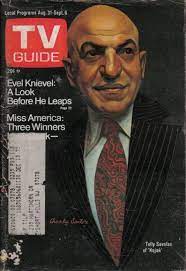

However, by the time Kojak finished in 1978 movie offers were beginning to dry up. Savalas’s identification with the one role was so complete that others had been hard to come by – they were either cameos, as in Capricorn One (1978) or The Muppet Movie (1979), or second goes at popular films, such as Beyond the Poseidon Adventure (1979) and Cannonball Run II (1983). Understandably, since he would always be a star in that medium, television offered frequent work, as when he played the Cheshire Cat in an all-star Alice in Wonderland (1985) and his old role alongside Ernest Borgine in The Dirty Dozen: the Deadly Mission (1987) and The Dirty Dozen: the Fatal Mission (1988).

In 1989 he again played Kojak – but not for Universal and CBS, as before. ABC had lured Burt Reynolds back to television to play a gumshoe, BL Stryker, but Reynolds was not prepared to appear again on a weekly basis, so The ABC Saturday Mystery rotated four different shows, with Jaclyn Smith as Christine Cromwell and two gentlemen from the past – Peter Falk as Columbo and Savalas as Kojak. Savalas insisted on New York’s being used for the locations and not, as before, Los Angeles standing in for New York. To a journalist watching the shooting he said, ‘C’mon, willya? I was born in this city . . . Raised in the neighbourhood, right? I speak the language. So Telly and Kojak are one and the same. That’s what makes the show interesting for me – and easy. I’m basically playing myself to a large extent – a street-smart fella with the soul of a pussycat.’

He admitted that the character was older and wiser, but the verdict of the press was that he was older and very tired. ABC dropped Kojak after the contracted four episodes (which were not seen in Britain).

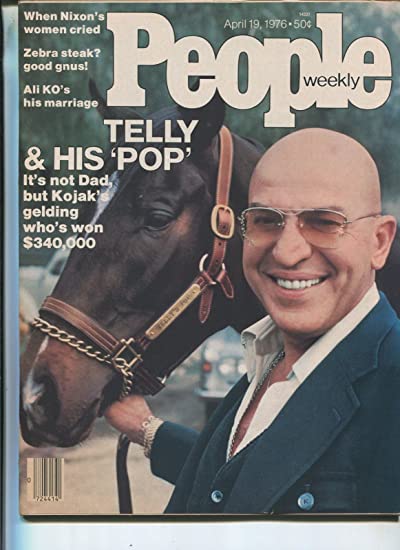

Savalas used his fame as Kojak to become a singer, with indifferent results as far as his records were concerned, but he did appear at the 1974 Oscar ceremony, singing ‘You’re so Nice To Be Around’ from Cinderella Liberty. In 1992 he opened ‘Telly’s Sporting Bar’ in the Sheraton – where he lived in Los Angeles – at Universal City, featuring mementoes of Kojak.

Savalas liked to be recognised – indeed, he revelled in his fame. He was only slightly ambivalent, declaring that television was ‘so powerful it can wipe out anything you’ve done in the past’. He went on, ‘I won’t mention names, but I remember sitting with two major motion-picture stars. Here’s poor little Telly comin’ off a little TV show and people are comin’ up to me and askin’ for my autograph. And I look at these two global personalities alongside me and nobody’s askin’ them. How come? Because they didn’t recognise them. The power of TV, my friend.’