SEAN CONNERY (WIKIPEDIA)

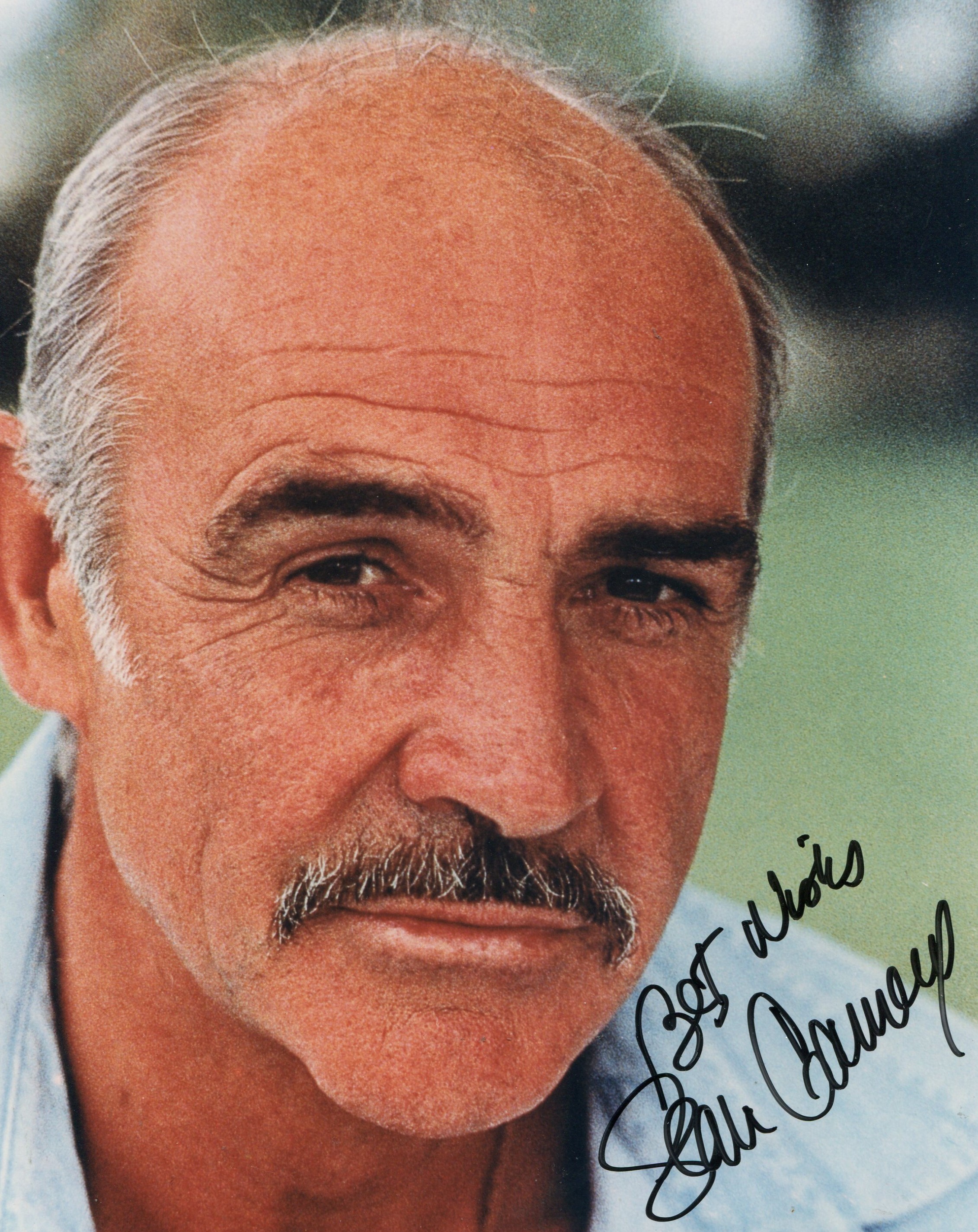

Sean Connery is a retired Scottish actor and producer, who has won an Academy Award, two BAFTA Awards, one being a BAFTA Academy Fellowship Award, and three Golden Globes, including the Cecil B. DeMille Award and a Henrietta Award.

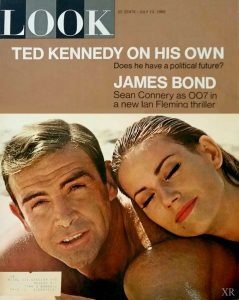

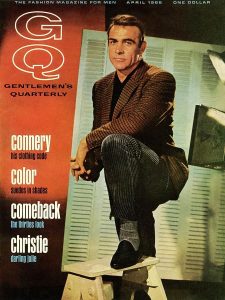

Connery was the first actor to portray the character James Bond in film, starring in seven Bond films (every film from Dr. No to You Only Live Twice, plus Diamonds Are Forever and Never Say Never Again), between 1962 and 1983.[1] In 1988, Connery won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role in The Untouchables. His films also include Marnie (1964), Murder on the Orient Express (1974), The Man Who Would Be King (1975), The Name of the Rose (1986), Highlander (1986), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), The Hunt for Red October (1990), Dragonheart (1996), The Rock (1996), and Finding Forrester (2000).

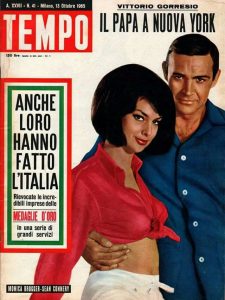

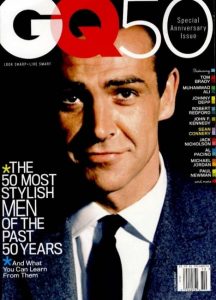

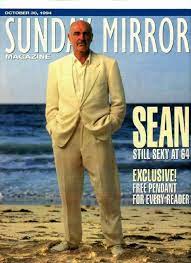

Connery has been polled in The Sunday Herald as “The Greatest Living Scot” and in a EuroMillions survey as “Scotland’s Greatest Living National Treasure”. He was voted by People magazine as both the “Sexiest Man Alive” in 1989 and the “Sexiest Man of the Century” in 1999. Connery was knighted in the 2000 New Year Honours for services to film drama.

THE TIMES OBITUARY IN 2020:

Sean Connery was nobody’s first choice to play the lead in the inaugural James Bond film, Dr No. Cary Grant, Rex Harrison and David Niven declined the part. Other big-name actors including Roger Moore, Michael Redgrave, Patrick McGoohan and Trevor Howard were considered but rejected. In desperation Albert “Cubby” Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, the producers, turned to Connery — a little-known, scarcely trained actor from a Scottish slum who was strikingly handsome and well built, and had impressed in a few minor roles.

Broccoli had his wife, Dana, watch a clip of Connery in a Walt Disney film called Darby O’Gill and the Little People and she was captivated. “That’s our Bond!” she cried. The two producers interviewed him in their Mayfair office, liked his confidence (“he looked like he had balls,” Broccoli said) and offered him a fee of £5,000. Others were still not convinced. The producers sent clips of Connery to United Artists in Hollywood, who cabled back: “See if you can do better.” Ian Fleming, Bond’s Eton-educated creator, remarked: “He’s not what I envisioned . . . I’m looking for Commander Bond and not an overgrown stuntman.” Terence Young, the film’s patrician director, had to do a latter-day Henry Higgins, taking the “rough diamond” from an Edinburgh tenement to posh Mayfair restaurants, introducing him to his bespoke tailor, teaching him how to walk, dress, speak and eat.

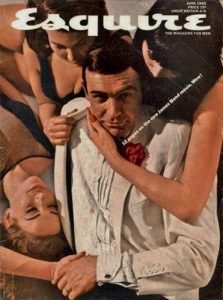

Yet when Dr No was released in 1962 it was a sensation, a cultural hurricane that shook up the film industry just as the Beatles were transforming music, the Pill was triggering a sexual revolution and President Kennedy was rejuvenating America.

With its Jamaican sun, glamorous women, transatlantic jets and fast cars, Dr No thrilled austere, joyless postwar Britain, and much of the rest of the world. With the immortal words “Bond . . . James Bond”, Connery introduced himself not only to the beautiful Sylvia Trench (Eunice Gayson) across a gaming table in a London casino, but to millions of delighted filmgoers. With an unforgettable scene where the erotic Honey Ryder (Ursula Andress) emerges from the azure Caribbean wearing only a white bikini and a diving knife, he began his relationship with the first of many stunning “Bond girls”. Suave, languid, witty, oozing charm and sexuality, and with just a hint of menace, Connery became one of the world’s biggest film stars almost overnight.

He went on to make four more Bond films over the next five years, wearing a toupee to conceal his receding hairline, before he tired of the role and fell out with the producers. Twice more, in 1971 and 1983, he returned to play Bond but without the verve and success of those first five films.

Out of Bondage, as it were, Connery greatly expanded his repertoire, appearing in some notorious arthouse flops as well as numerous box-office hits but winning praise for the depth and range of his characters. He was the consummate professional, never acting the prima donna and often performing his own stunts. He won the Oscar for best supporting actor in 1988, a lifetime achievement award from the American Film Institute in 2006, and two Baftas.

Connery gave generously to good causes and was knighted in 2000, an award he would probably have received years earlier had he not been such a fervent supporter of Scottish independence. For all that, he will inevitably be remembered as the first James Bond, and as the best of them all. As the film critic Pauline Kael once put it, “Women want to meet him, and men want to be him. I don’t know any man since Cary Grant that men have wanted to be so much.”

His is a genuine rags-to-riches story. He was born Thomas Sean Connery in Edinburgh in 1930 and known throughout his youth as Tommy. His father, Joseph, a Roman Catholic of Irish descent, worked variously at a rubber mill and as a lorry driver, while his Protestant mother Euphemia “Effie” (née McLean) was a cleaner. He and his younger brother, Neil, were raised in a tenement flat in Fountainbridge with no bathroom or hot water and precious little money; his crib was the bottom drawer of a dresser. “We were poor, but I never knew how poor until a social worker told me,” he said to a friend in later life. Even in his sixties a bath was still “something special”.

From the age of nine Connery delivered milk before school, and did a shift at a butcher’s shop afterwards. He lost his virginity in an air raid shelter to a woman in the Auxiliary Territorial Service when he was 14. Around the same time he left Darroch secondary school and found full-time work delivering milk for the Co-op dairy in a horse and cart. After his rounds were done he indulged his real passion: football. His nickname was “Big Tam” because he was 6ft 2in and hairy-chested. At 17, largely to escape from what he called the “grim no man’s land” of Fountainbridge, he signed up as a Royal Navy volunteer, but was discharged two years later with duodenal ulcers. More menial jobs followed until he trained as a French polisher under a British Legion programme for ex-servicemen. Thereafter he found himself polishing coffins for a living. Sometimes he slept in them to save his bus fare home.

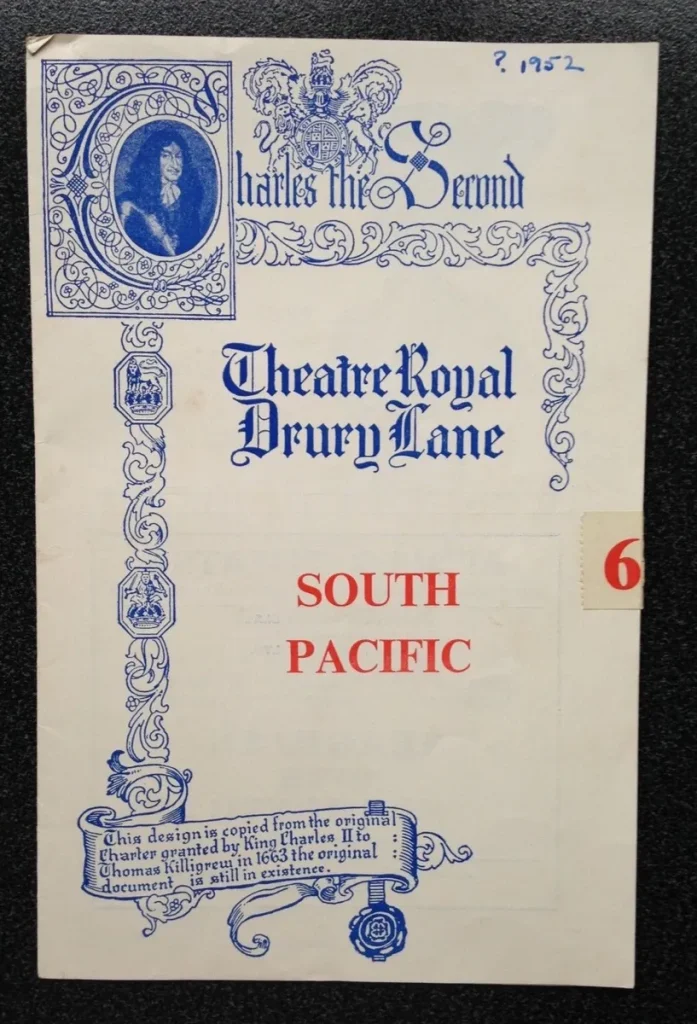

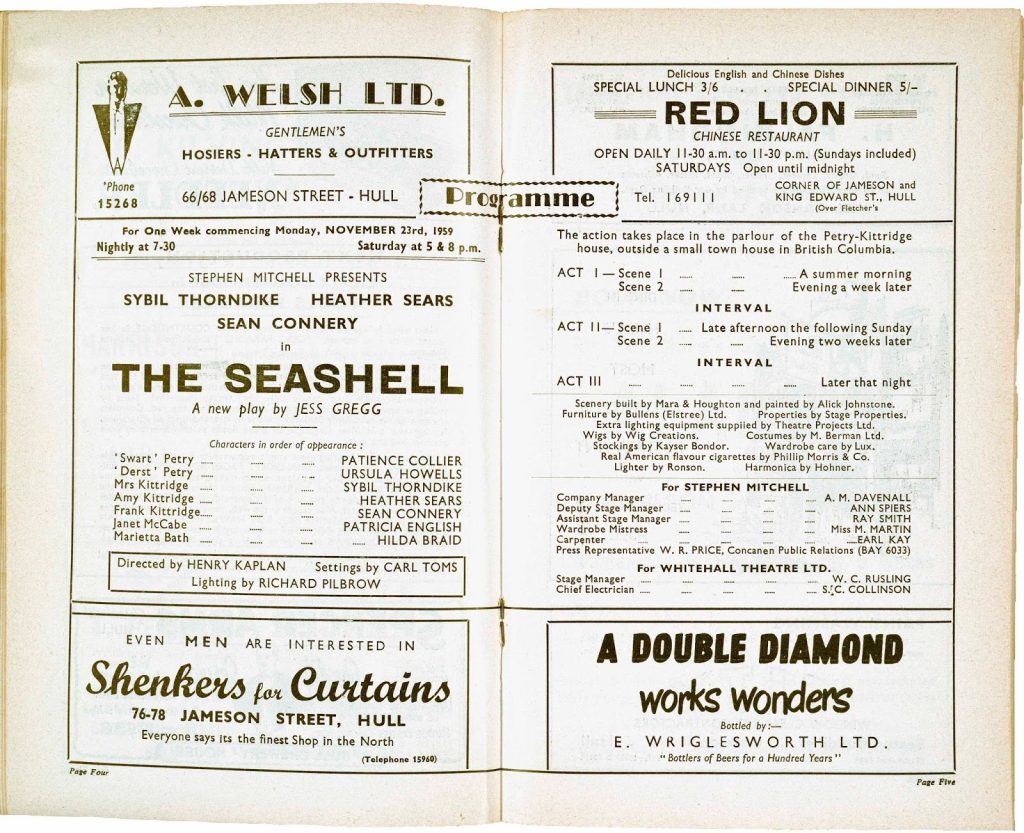

That job did not last long either. He worked as a lifeguard at an outdoor swimming pool, a bouncer and an apprentice machine worker at the Edinburgh Evening News, and briefly joined Bonnyrigg Rose as a professional footballer. Having taken up body-building, he posed as a model at Edinburgh College of Art for ready cash, and entered the Mr Universe contest in London. He came only third in the junior section, but then heard that actors were needed for the British run of the American musical South Pacific.

Taking his middle name Sean for the stage, Connery got a chorus part on the strength of his physique alone, and signed up for a two-year tour of the UK. The cast formed its own football team and played a Manchester United junior team, where Matt Busby was among the spectators and afterwards Connery was offered a trial. He was dissuaded by Robert Henderson, one of the show’s leading American actors, who told him: “If you choose soccer you may have another ten years, but as an actor you could go on till you drop.”

Henderson was impressed by Connery’s intelligence and ambition, and became his mentor. He encouraged his protégé to lose his broad Scottish accent and to educate himself by reading widely. Connery devoured the works of Tolstoy, Proust, Ibsen, Turgenev and Joyce that Henderson gave him.

He secured Connery a bigger role in South Pacific; that of Lieutenant Buzz Adams. Henderson later found him small parts in various London plays until, in 1957, Connery secured his first significant role, playing a fallen boxer in a BBC reworking of Requiem for a Heavyweight. It had been made famous in America by the actor Jack Palance. When Palance refused to travel to London, the director’s wife suggested Connery. “The ladies will like him,” she said. Connery had had no formal training, but his acting career was launched.

He soon found himself playing opposite Lana Turner in Another Time, Another Place. He knocked out Turner’s gangster boyfriend, Johnny Stompanato, after he had arrived in the studio, pointed a gun at Connery and accused him of having an affair with Turner (he almost certainly was). The film flopped, and one scathing reviewer wrote that young Connery “will not, I guess, grow old in the industry”.

Later that year he appeared in Eugene O’Neill’s playAnna Christie as the lover of a prostitute struggling for redemption played by Diane Cilento, a young Australian actress. He was captivated by her, though she was married with a baby daughter, Gigi. After his first visit to Hollywood to make Darby O’Gill she contracted tuberculosis and he briefly put his career on hold to look after her, turning down the chance to appear with Sophia Loren in El Cid.

They married after the premiere of Dr No in 1962, by which time she was divorced and seven months pregnant with Connery’s child. Jason, born in January 1963, would board at Gordonstoun and eventually follow his father into acting, once playing Bond’s creator in an American television production called The Secret Life of Ian Fleming. With the proceeds from Dr No, Connery, his wife, son and stepdaughter moved into a large house overlooking Acton Park in west London.

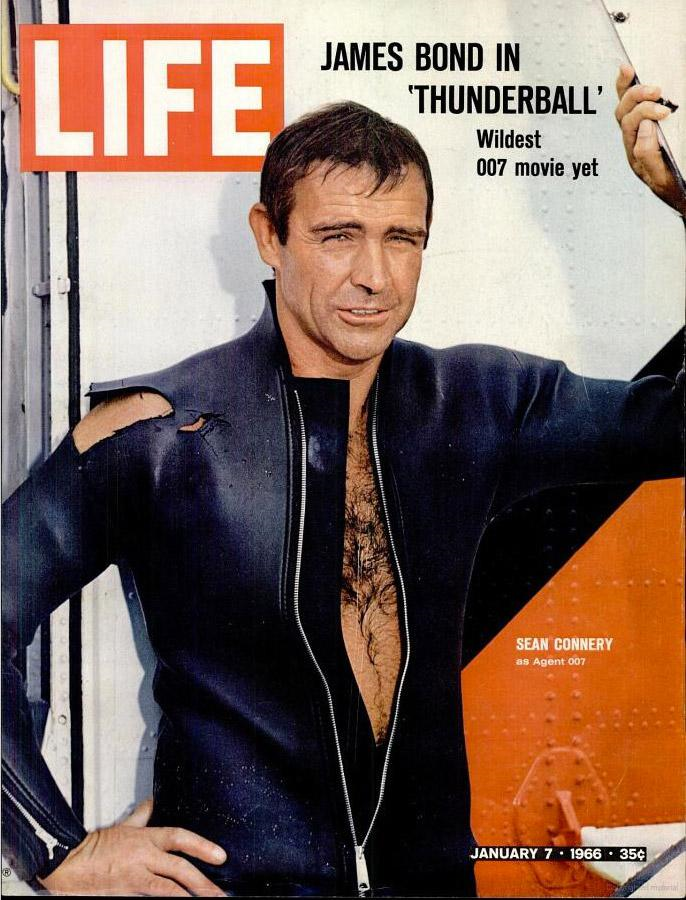

In quick succession Connery went on to make From Russia with Love, Goldfinger, Thunderball and You Only Live Twice. They earned Connery ever greater fees, as much as $500,000 a film plus a percentage of the profits. However, the quality of the films fell away, his relations with Broccoli and Saltzman soured, and he felt increasingly trapped by the role and the relentless hounding by the media. “It’s finished. Bond’s been good to me, but I’ve done my bit. I’m out,” he declared after filming You Only Live Twice. “After this I will only do things that passionately interest me for the rest of my life.”

Anxious to establish himself as a serious actor, he turned to artier films, but they flopped. So did his appearance alongside Brigitte Bardot in Shalako, for which he received $1.2 million, and his turn in a Hitchcock film, Marnie, though he picked up some valuable tips from the director who encouraged him to speak more slowly and not to listen open-mouthed while others were talking. “The good people of Pocatello,” Hitchcock said, “will not be all that interested in your dental work.”

I’ve Seen You Cut Lemons, a play Connery directed with his wife in the lead role, also fell flat with audiences. Finally, in 1971 he agreed to do another Bond film, Diamonds Are Forever, tempted by a fee of $1.25 million plus future financing by United Artists for two films of his choice. It was far from the greatest Bond film, but broke box-office records and re-established the Connery brand.

In the following years there were big changes in his private life. He separated from Cilento after having a succession of affairs with models and actresses, including Jill St John, Lana Wood, Carole Mallory and Magda Konopka. He moved from their home in Putney to a flat overlooking the Thames at Chelsea Embankment, and they divorced in 1973. “Our careers were incompatible, not us,” he said, insisting the split was amicable.

Cilento, however, alleged in her 2006 autobiography that he had abused her mentally and physically, claims he denied. Connery had been quoted in a 1965 Playboy interview as saying, “I don’t think there is anything particularly wrong in hitting a woman, though I don’t recommend you do it the same way that you hit a man.” The remark caused controversy for years, and he refused to apologise when asked in 1987 by the interviewer Barbara Walters if he had changed his views; he maintained he had been quoted out of context.

Connery had learnt to play golf in preparation for a scene in Goldfinger and the sport became a passion. He played in pro-am tournaments with a single-figure handicap, and enjoyed rounds with fellow stars Tommy Cooper, Bruce Forsyth and the racing driver James Hunt. He was playing with Rex Harrison in Rome when he heard that Fleming had died, and so the pair played a second round in his honour using the Penfold Heart balls Fleming had prescribed for Bond in Goldfinger.

It was during a golf tournament in Morocco that he met Micheline Roquebrune, a French-Moroccan artist with three children. Both had won their respective competitions. They married in 1975 and set up home at Casa Malibu, an estate outside Marbella. Connery had left Britain because of its exorbitant tax rates, speaking of “the need to get out of the umbrella of parasites headed by people like [Denis] Healey [the chancellor of the exchequer]”. Roquebrune helped to push him back towards more commercial films, and some of his better performances. The Wind and the Lion was followed by John Huston’s version of Rudyard Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King in which Connery co-starred with Michael Caine. That was followed by Richard Attenborough’s epic A Bridge Too Far, but also failures including The First Great Train Robbery, Meteor and Cuba.

Connery’s career appeared to be entering another trough, which is one reason why, at 52, he chose to eat his words and make one more Bond film. Another was the $5 million fee. A third was his rivalry with Roger Moore, who had taken over the role. Never Say Never Again was to be produced by Jack Schwartzman in direct competition with Broccoli, who failed to stop it in the courts. Connery threw himself into the project but it was unsuccessful, losing out to Moore’s Octopussy. Roquebrune told a journalist the film had been “a nightmare” and one review concluded: “Let’s say never again.”

It was advice that Connery accepted, but his feud with Broccoli was not over. The next year, 1984, he sued Broccoli and his production companies. He claimed they had cheated him out of his rightful share of the profits from the first five Bond films and sought $225 million in damages. The action was settled out of court and the terms never publicly disclosed.

For nearly three years Connery retired from view, but in 1986 he bounced back with a masterly performance as a medieval Benedictine monk in The Name of the Rose, a film based on Umberto Eco’s novel. In the following year came his Oscar-winning role as a streetwise Chicago cop in the gangster movie The Untouchables. He received two standing ovations at the awards ceremony in Hollywood.

Connery had finally emerged from Bond’s shadow. During the next two decades he delivered some of his finest performances: in Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, as a Soviet submarine commander in The Hunt for Red October, as an ageing ethnobiologist searching for a cancer cure in the Amazon in Medicine Man, as a reclusive author in Finding Forrester, and as a professional thief in Entrapment. The only conspicuous failure was a film version of the TV series The Avengers that he called “a complete and utter f***-up”.

Meanwhile, his second marriage had survived his well-documented affair in the late 1980s with the singer-songwriter Lynsey de Paul, and Roquebrune remained devoted to him in his last years, which were blighted by dementia.

Immensely wealthy with homes in New York, Los Angeles and the Bahamas, Connery made his last film, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, in 2003. He announced his retirement in 2005, saying he was “fed up with the idiots” running Hollywood. He resurfaced in 2012 when he and Sir Alex Ferguson, the Manchester United manager and fellow Scot, gatecrashed Andy Murray’s press conference after he reached the final of the US Open.

His final film role was in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003)

Connery once said he had three great passions in his life outside his family: acting, golf and Scotland, of which Scotland was the greatest. One of his proudest awards was the freedom of Edinburgh, and he named his own Hollywood production company Fountainbridge Films. As a navy cadet he had had “Scotland Forever” tattooed on his arm, and even at the height of his fame he never forgot his roots.

In 1967 he made a documentary about the problems of the Clydeside shipbuilding industry called The Bowler and the Bunnet that, in his words, “rose without trace”, but it fuelled his appetite for social activism. Enraged by the destruction of Scotland’s fishing industry after Britain joined the Common Market in 1973, he began supporting the Scottish National Party (SNP). He used the proceeds from Diamonds Are Forever to endow the Scottish International Education Trust, which he had founded to provide bursaries for underprivileged Scots.

In 1992 he formally joined the SNP, having helped it make a party political broadcast for that year’s general election. He supported the party financially from 1995 to 2001, campaigning for a “yes” vote in the 1997 devolution referendum and for the SNP in the first Scottish parliamentary elections two years later. Donald Dewar, Labour’s Scottish secretary, twice vetoed his nomination for a knighthood because of his support for the SNP, but Connery, wearing Highland dress, was finally knighted by the Queen at Holyrood Palace in 2000.

Although Connery, then 84, did not campaign in the 2014 referendum on Scotland’s independence, he issued a statement supporting the Yes campaign. “I am for a Scotland that makes her own decisions, a sovereign state that will be a voice in Europe and around the world,” he wrote in Being a Scot, a book celebrating Scottish culture and history that he co-authored in 2008.

In that same book Connery recalled how he had returned to Edinburgh for a recent film festival, and had surprised a taxi driver by naming every street he passed. “How come?,” the cabbie asked, not recognising his passenger. “As a boy I used to deliver milk around here,” Connery replied. “So what do you do now?” the cabbie asked. “That,” Connery wrote, “was rather harder to answer.”

Sir Sean Connery, actor, was born on August 25, 1930. He died in his sleep on October 31, 2020 aged 90