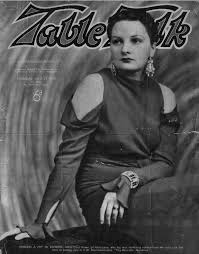

Coral Browne- An appreciation from ‘The Los Angeles Times’ in 1991.

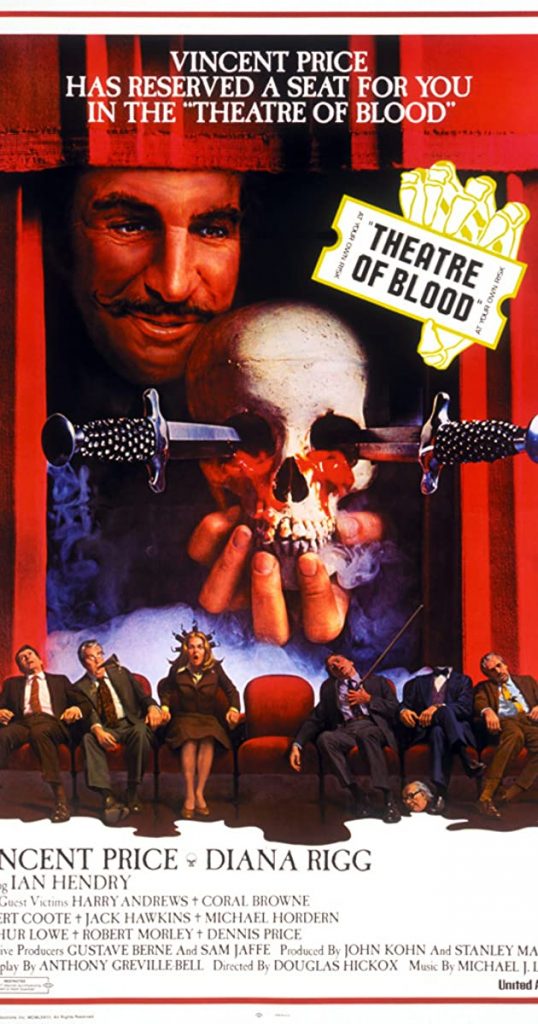

Coral Browne met Vincent Price while making a wonderfully campy melodrama, “Theatre of Blood,” in London in 1972.

Price was playing a hammy Shakespearean actor driven round the bend by bad reviews and taking his revenge by bumping off the critics in fine Shakespearean fashion, abetted by Diana Rigg as his daughter.

Coral Browne was one of the victims, but she and Price fell in love, were married soon after and had 17 vivid years together.

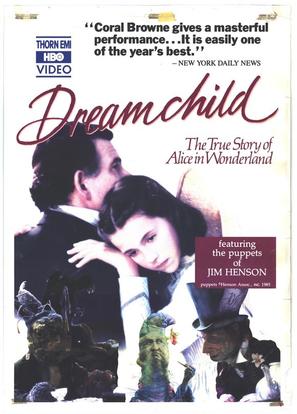

Browne was a distinguished Australian-born actress, one of whose memorable roles was in “Dream Child,” in which she played the Alice–for whom Lewis Carroll wrote “Alice in Wonderland”–as an elderly woman remembering it all.

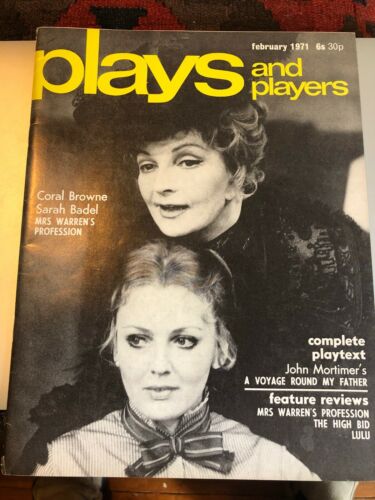

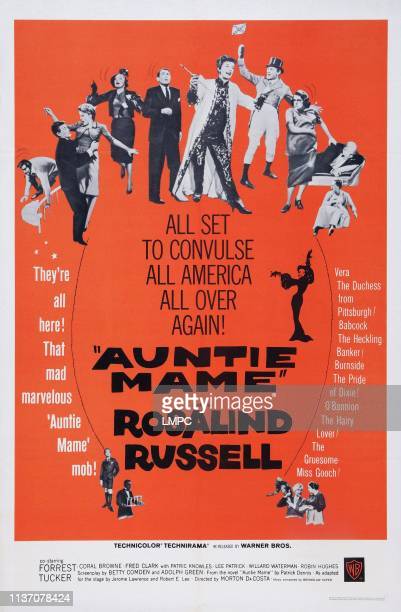

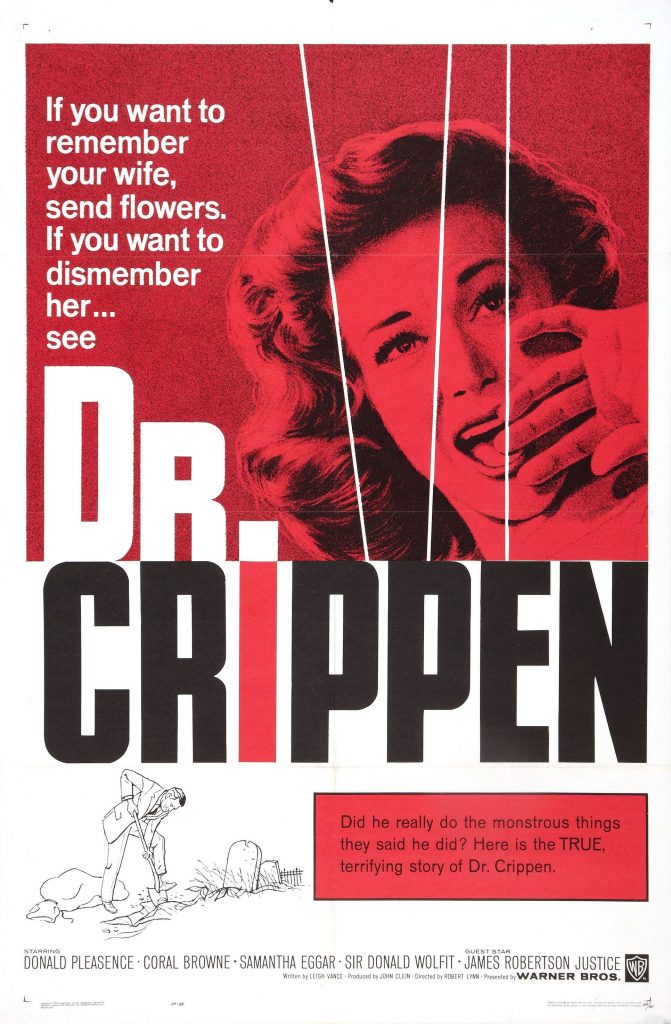

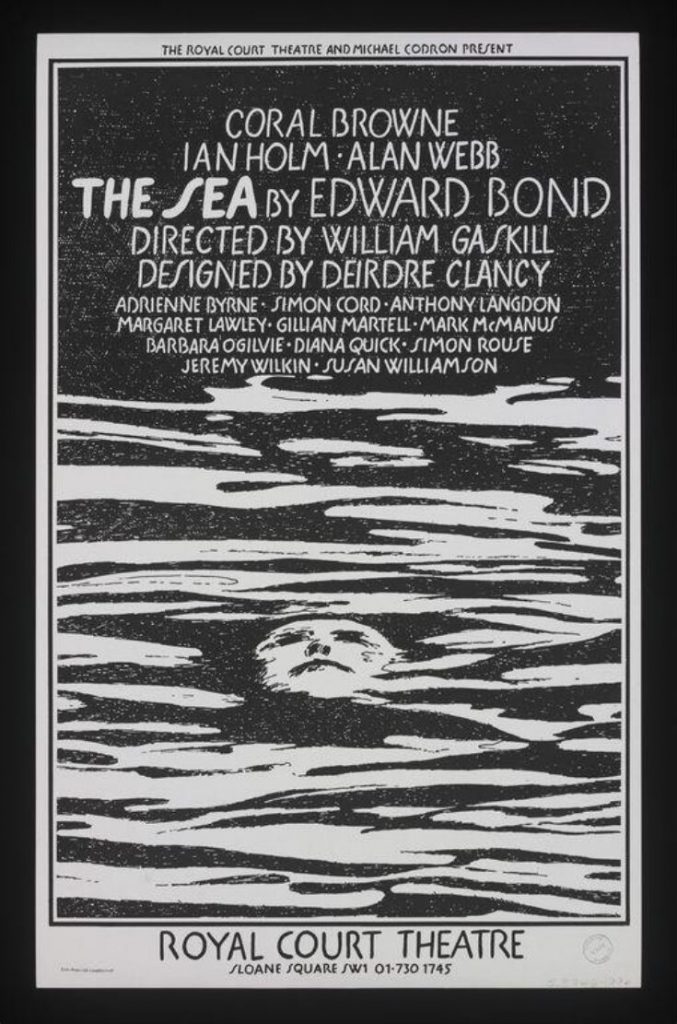

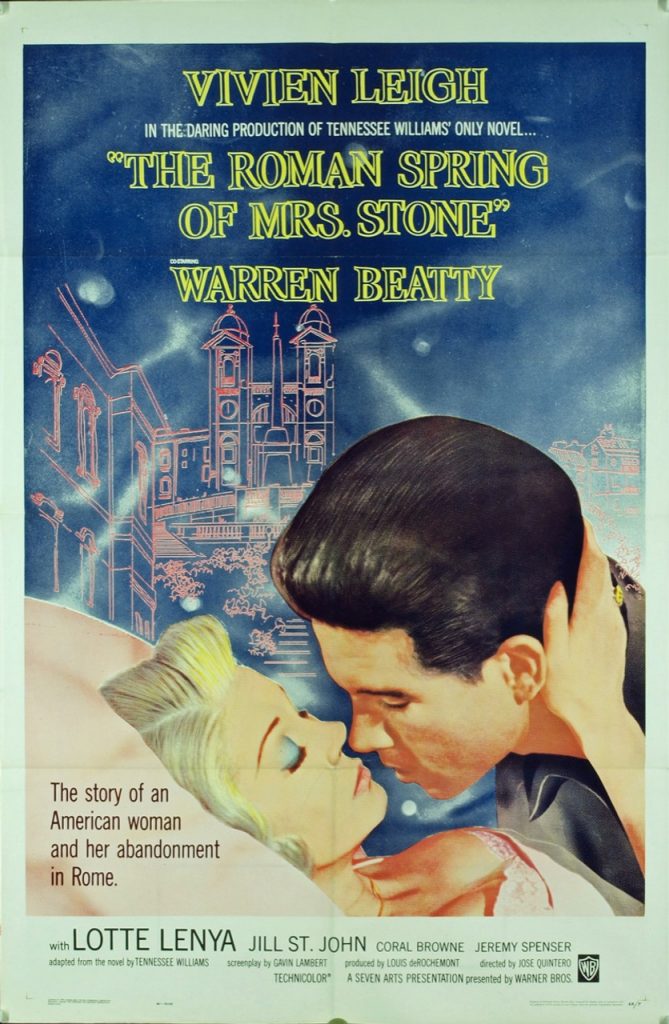

More often, Browne played quite worldly ladies with sharp minds and tongues to match, as in “Auntie Mame” and “The Killing of Sister George,” “The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone” (with Vivien Leigh and a young Warren Beatty) and “The Legend of Lylah Clare” with Kim Novak.

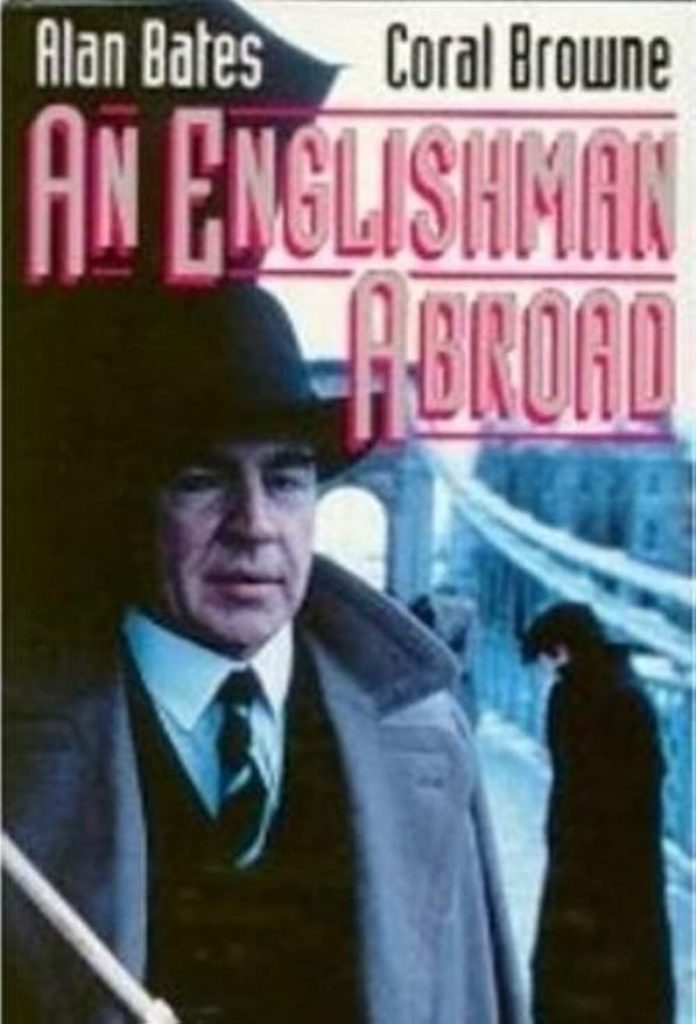

She was in Moscow, playing Gertrude, Hamlet’s mother, in a touring production of the play when her dressing room was invaded by the notorious British traitor Guy Burgess, then living in a shabby alcoholic exile. He was messily sick in her wash basin, stole a bottle of her whiskey and peremptorily demanded that she come to lunch.

His motive was to hand her his measurements and ask her to have some suits and other items, including custom-made pajamas, run up for him by his London tailors.

Browne dined out on the story for years until Alan Bennett heard her tell it one evening and wrote a teleplay, “An Englishman Abroad,” which John Schlesinger directed and in which Alan Bates played Burgess and Browne played herself. It was–is–funny, sad and angering in almost equal measure.

Browne was, in fact, a delicious raconteuse, one of those women (not all of them necessarily actresses) who see themselves continually at the center of dramas ranged anywhere between farce and tragedy, depending on events, and who report on them with immense verve and humor.

She kept a wickedly discerning eye on the follies and idiocies of the world but she was just as often amusing as the author of her own mischances.

On a lecture cruise a few years ago, she had left a new and crucial partial bridge at home. There began a port-by-port, consulate-by-consulate, cruise line office-by-cruise line office struggle to get the missing dentistry airshipped to the next port of call. It did not catch up until the cruise was over.

The sequence could have been played in rage–she was forced to eschew some of the ship’s most ravishing and chewable cuisine–but her bulletins made it all seem to be a hilarious and suspenseful slapstick misadventure.

Someone like the late Cornelia Otis Skinner could have written a whole book out of it.

Browne was a remarkably beautiful woman who could manage an elegant hauteur and a madcap insouciance with equal conviction. Yet the hauteur seemed more a pose than the insouciance, which, combined with a warm generosity of spirit, earned her a wonderful circle of friends in and out of the theater.

The peril of being a gifted international actress of strong character is that you may well play character roles to great acclaim and enduring respect, as Gertrude to someone’s starry Hamlet, but miss the kind of superstardom that moguls understand.

Then again, the high respect of one’s peers, which Coral Browne earned during a long career, is sometimes denied the superstars. Her credits are secure.