‘Guardian” tribute by David Thompson in 2002.

There is no hint of an anniversary, so far as one can tell: James Stewart was born in 1908 and he died just five years ago, in 1997. Yet why should we require any pretext of the National Film Theatre if they have a mind to run 25 of his films? I say that not out of any banal thought that Stewart was one of the most endearing actors in the movies, a role model for us all and automatic casting as the decent American everyman. There’s some truth in all of those assumptions, and you can see it in pictures like It’s a Wonderful Life and The Shop Around the Corner. If that’s all you’re looking for. Or if you’re content with the thought that you’re going to have a really nice, comfortable, sweet time. Cosy, even. No, the real reason for running James Stewart movies is because he’s someone you have to stay wide awake with. In other words, I’ll settle for him as Everyman so long as you are prepared to allow that every George Bailey has some bad moments.

Yes, it’s certainly true that, on his way towards universal public affection, Jimmy Stewart was shamelessly appealing: very nice-looking without having a trace of sexual menace, high-voiced (his Easy to Love in Born to Dance may be closer to the aural range of dogs than of men), polite, sincere, honest. That’s why Frank Capra cast him in Mr Smith Goes to Washington – because you could believe that Stewart could break down in tears over his failure to convince a mean old Senate about the workability of the constitution and still not surrender his boyish manhood. In much the same way, Stewart was adorable in wide-eyed contests with Margaret Sullavan in such films as The Mortal Storm and The Shop Around the Corner.

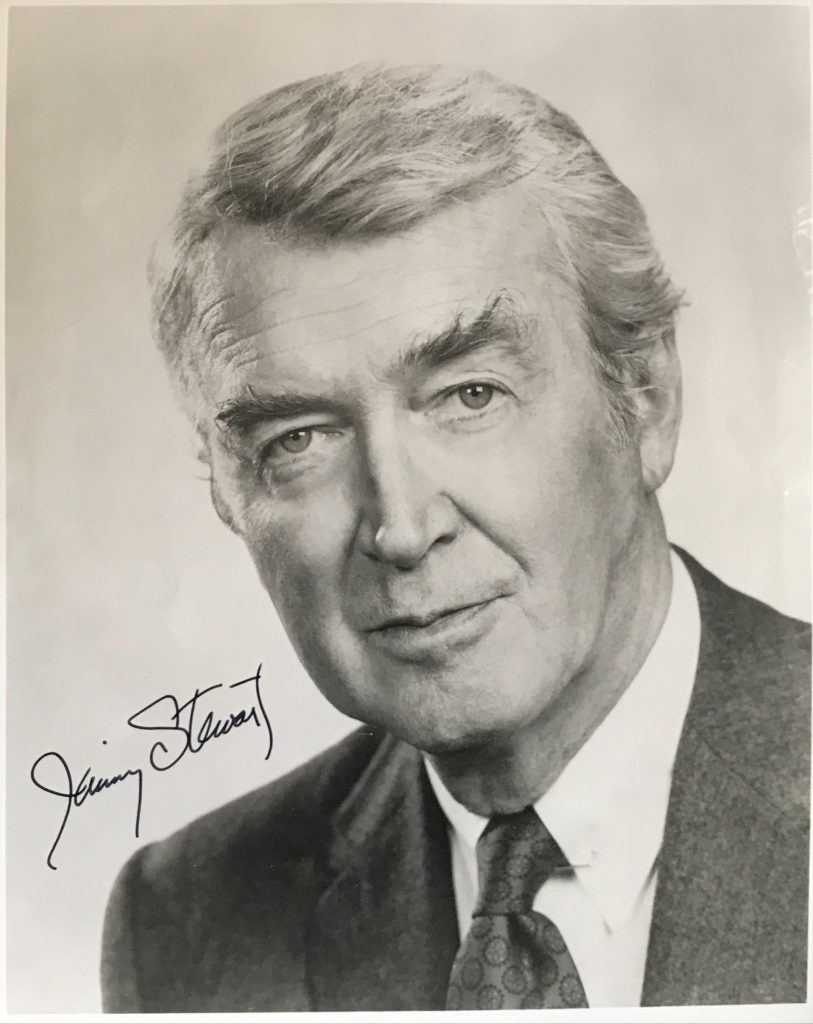

Sullavan and Stewart are one of the great romantic couples of the late 1930s: her hushed voice seemed to urge his to be deeper and quieter. They were old friends. Sullavan, who was younger but ahead of him on stardom’s tree, insisted on him being in several pictures and then acted as if she was crazy about him. Who knows? Stewart’s later air of fidelity and reliability did not quite fit with the way he had been seen once with every attractive woman in town. Once married, Jimmy stayed that way, but it was 1949 before he agreed to settle down. Thereafter, he and Gloria were joined in perpetuity. They had four children. Jimmy would recite his poetry on television. And Gloria watched over him.

All of which is lovely to remember. On the other hand, Jimmy Stewart was a kid from a well-to-do family in rural Pennsylvania – not top-drawer, but getting up there. He graduated from Princeton with a degree in architecture, even if he spent as much time with the drama club as with plans for buildings. All of which only went to show that the country-boy manner, and especially the stumbling way of speaking, were pretty calculated: they got the girls first, and then the movie roles. In five years, he went from his debut to an Oscar in The Philadelphia Story. He is very good in that film, but if you recollect that he was playing with Cary Grant you can begin to appreciate Stewart’s shy, oh-shucks way of stealing girlfriends, plum parts and big scenes.

None of which means to suggest that James Stewart was less than a good man and officer material. He thoroughly went off to war: there was a six-year gap in his career during which he flew bombers over Europe, and then recovered from something close to a nervous breakdown. And that kind of detail is no more than proper biography for the changed actor who came back after the war, and who later became the first actor to get profit participation on his movies. Sometimes that coup has been ascribed entirely to the machinations of his agent, Lew Wasserman. But surely it’s a little naive to think that Stewart wasn’t himself very interested in the radical departure in contractual terms that made him a fortune.

The more you see It’s a Wonderful Life, the more clear it is that George Bailey nurses not just dismay and frustration at the small-town life he has settled for, but rage and despair, too. It’s a Wonderful Life, coming just after the end of the second world war, was meant as a reminder of provincial American virtues, and of there being no place like home. But it’s also a desperate farewell to the wider world, to adventure, to all those American yearnings to go beyond old frontiers. There’s an agony in the film that’s not wrapped up and put away by the happy ending. And no one could have done it but Stewart.

This was a warm-up for the increasingly tough, selfish and lonely cowboy hero he played for Anthony Mann – in Bend of the River, Winchester 73, The Naked Spur, The Far Country and The Man from Laramie. And those were the films on which Jimmy was taking a straight cut of the profits. Again, it’s far-fetched to think that Stewart wasn’t involved in the novel darkness of those films.

It would be as crazy or as innocent, I think, to assume that Alfred Hitchcock wasn’t an avid viewer of those Mann westerns. Hitch had used Stewart in Rope – where he is the figure of decency, horrified by the young murderers. But then, in the 50s, in two major films, Stewart was cast as someone whose slow speech had as much stealth as charm. In Rear Window, the humour was still there. That picture plays quite nicely as a knockout love story for one of Grace Kelly’s magazines. But then notice how far the nocturnal spying in Stewart’s character is indecent, malicious, eager for the worst. It’s brilliant casting that gently draws an inner coldness forth.

But it is as nothing compared with the authentic depression and cruelty that beset Scotty in Vertigo. I’m not sure any other actor in the late 1950s could have done that film without leaving its fantastical element nakedly exposed. It’s because we expect to like Stewart that we are drawn into his neurosis – and then it’s too late.

Then came Anatomy of a Murder, for Otto Preminger, in which Stewart plays the Michifan lawyer, a confirmed bachelor, fisherman and jazz fan, as well as an advocate who is happy to try out every bit of rural twang and country earnestness – until George C Scott makes it clear how fully he appreciates the game. Anatomy of a Murder has a view of the legal process that is all theatre, and in casting Stewart, Preminger coolly exploited all of Stewart’s lifelong mannerisms. Which Stewart gracefully allowed. Because by then he knew how close he was to being an institution.

He went on a long time, though only a few years after the death of his Gloria. He was sad and grumpy by then – though worse than that. A greater darkness had crept in. Of course, he could still act (witness him as the doctor in The Shootist who has to tell John Wayne he is dying), and on television talk shows he could be the dreamy charmer, the semi-senile version of that guy from Harvey or No Highway, so absent-minded that he might charm Marlene Dietrich out of her pants. Which he had managed in his day.

Not that anyone bore a grudge or said a mean word about him. If there were scores of ladies, he must have treated them nicely or had something they wanted. I think that’s the secret – in films of diverse kinds, James Stewart had that thing unique to stardom and its great power of fantasy. We wanted to be him, and we wanted to be liked by him. In these more cynical days, I doubt if anyone could come on so likable without seeming a sham or a confidence trickster.