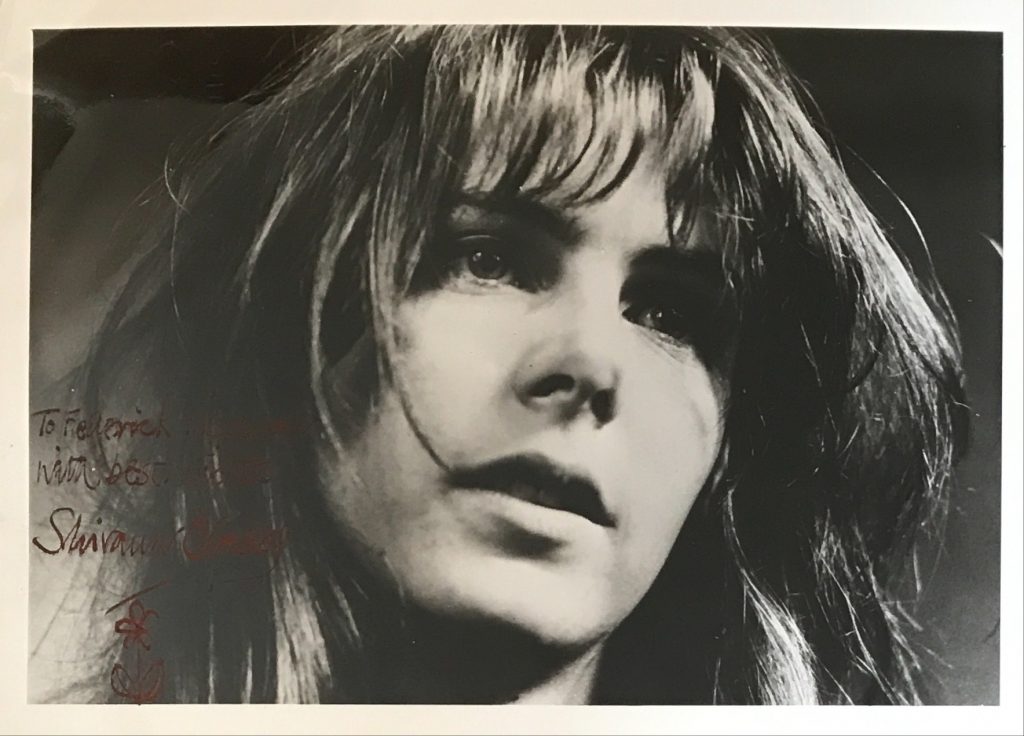

Shivaun O’Casey interview in “The Irish Independent” in 2018.

Shivaun O’Casey can clearly remember the moment when she realised just how much some Irish people hated her father. It was February 1955 and the 15-year-old had made her first trip to Ireland for the premiere of Sean O’Casey’s new clerical drama, The Bishop’s Bonfire. While religious groups protested outside the Gaiety Theatre, inside there were cries of “Blasphemy”, “Sacrilege!” and “Get out, ye dirty Protestants!”

“It was a very exciting evening,” recalls Shivaun, now an elegantly spoken 78-year-old woman with a ready laugh. “Leaflets were thrown down on our heads from the gallery and my mother Eileen whispered to me, ‘They’re trying to make it like the Plough, dear.'”

Even as a teenager, Shivaun understood the reference. At the Abbey Theatre in 1926, the first production of The Plough and the Stars had been disrupted by rioters who felt outraged by its less than reverential depiction of the Easter Rising. An equally annoyed WB Yeats famously arrived on stage himself and shouted at the protesters, “You have disgraced yourselves again!”

When Shivaun revisits the Gaiety later this month for another performance of The Plough and the Stars, it seems safe to assume that the atmosphere will be a lot more respectful. Previously staged at the Abbey and Lyric Hammersmith in London, this is a radical, modern-dress interpretation that begins with the sickly tenement girl Mollser singing ‘Amhrán na bhFiann’ before coughing up blood. Although Shivaun has no formal connection with the production, she was consulted by director Sean Holmes during its planning stages and is happy to give it her endorsement.

“I could see that he had a great love for the play,” she says. “That was so important to me. Plough isn’t performed as often as Juno and the Paycock or The Shadow of a Gunman because it needs so many actors, but this has a brilliant cast – it’s definitely of the best versions I’ve ever seen.”

As O’Casey’s last surviving child, Shivaun feels both proud and protective of his legacy. In particular, she is keen to dispel the popular notion that he was a bitter, cantankerous man who ended up hating his native country.

“The truth is that he always loved Ireland and kept in close contact with it,” she insists. “He just didn’t like the conservative political direction it had taken.”

Shivaun was born in 1939, by which time O’Casey had become fed up with his treatment by the Irish literary establishment and moved to south-west England. Among the family friends who sent letters of congratulations were Nobel laureate George Bernard Shaw and future British prime minister Harold Macmillan. Shaw congratulated Eileen on producing a girl after two boys, declaring: “Sisterless men are always afraid of women.”

O’Casey, his daughter points out, was something of an early feminist himself. “As a boy, he had bad eyesight and would sit quietly for hours, just listening to his mother and her friends talking. He used to say that if presidents and prime ministers were women, there would be no more war because they understood what it’s like to lose a child.”

Growing up in Devon, Shivaun did not realise at first that her father was anything special. She fondly remembers the constant clack-clack of his typewriter and him singing out loud when things were going well. She would then go into his room, where he often greeted her with the words, “would you like a piece of fudge?” At the age of eight she listened to Juno and the Paycock on the radio and felt “very nervous that perhaps I wouldn’t like it. Fortunately, I thought it was wonderful”.

When Shivaun decided she wanted to be an actress herself, Sean was not particularly keen. “He said it was a thankless profession and I should be a scene designer instead, because then at least you’ve got something to hang on the wall.”ADVERTISEMENT

She defied his advice and later enjoyed success as a director, too, co-founding the O’Casey Theatre Company that staged classic Irish plays around this country and the US.

Shortly before Sean’s death in 1964, John Ford began directing a wildly romantic and inaccurate film about his early life called Young Cassidy. Although Shivaun herself had a cameo role as Lady Gregory’s maid, she claims never to have actually watched it. “I just didn’t think much of the script. It gave such a wrong impression of life in the Dublin tenements, with chickens running about and people throwing chamber pots out the window. I’ve got a copy at home, but I could never get past the first 10 minutes – isn’t that awful?”

Shivaun made a documentary about her father in 2005 and is currently working on a memoir based around the family’s correspondence. She is also looking forward to visiting Dublin again, where her granddaughter is a drama student at the Lir Academy. She keeps a close eye on Irish current affairs and is fervently hoping for a Yes vote in next month’s abortion referendum.

The Plough and the Stars still endures, she believes, because it has a timeless message about the suffering of ordinary people in conflict situations.

“When I directed the play in 1997, it felt relevant due to the war in Bosnia. Today it’s Syria. If Sean was here today, he’d be delighted by the progress Ireland has made. But he’d also be writing about the things that still need to change.”