Fredric March obituary in “Los Angeles Times” in 1976.

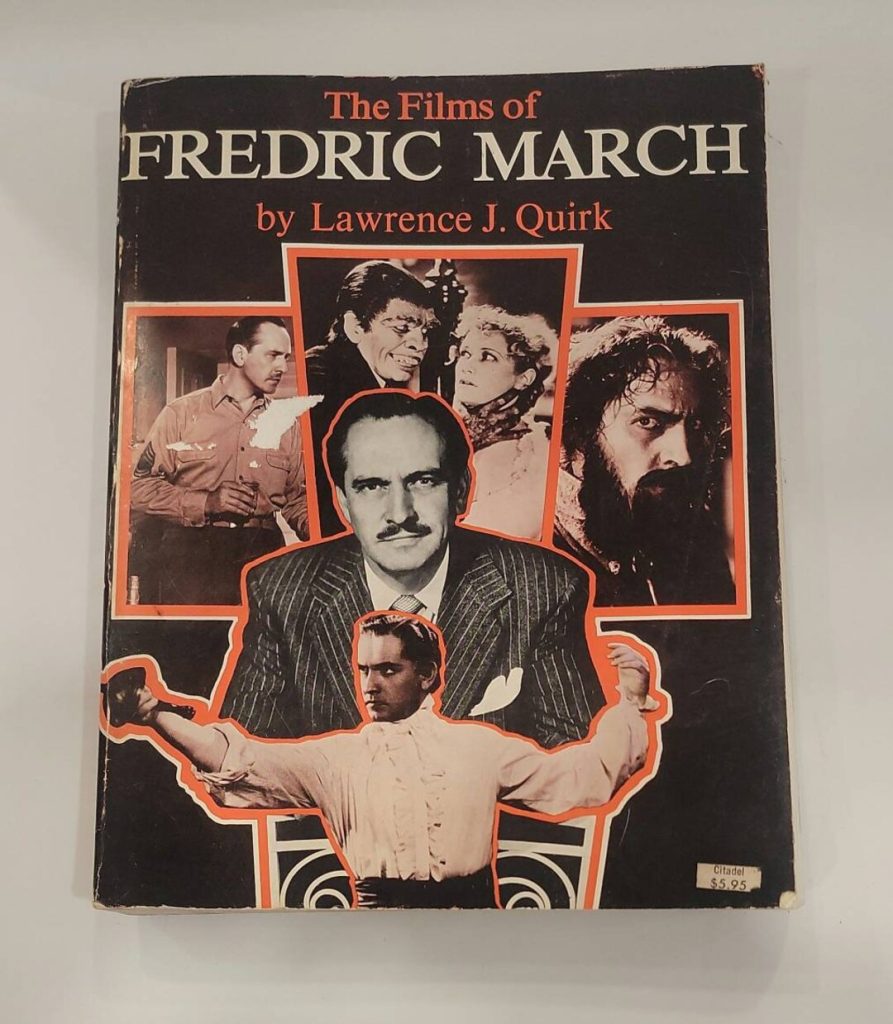

Fredric March, a two-time Academy Award winner whose stage and film acting career spanned more than half a century, died Monday at Mt. Sinai Hospital.

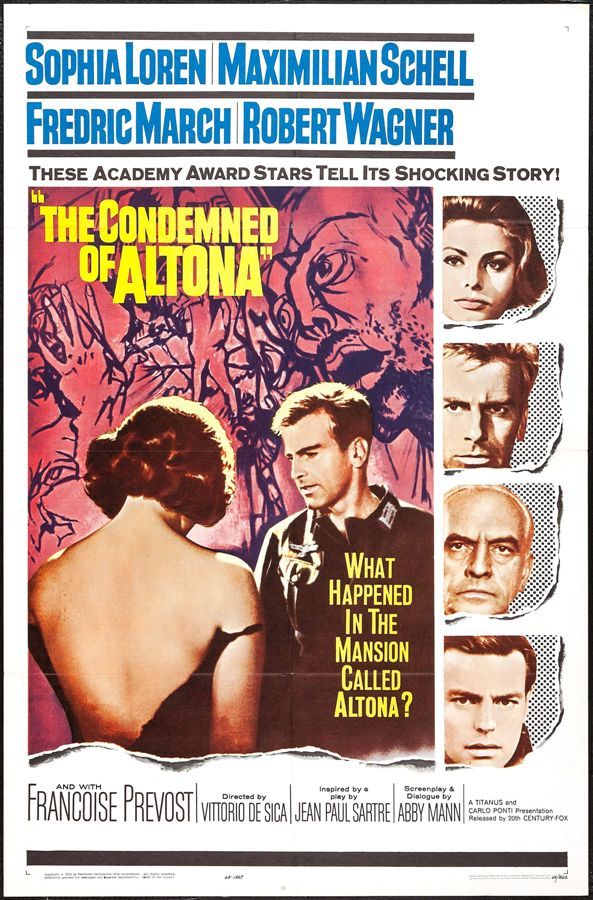

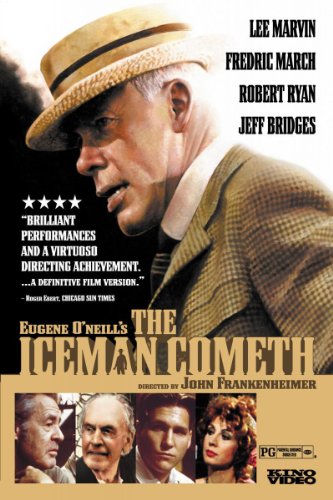

March was 77 and had been in semi-retirement for several years. His agent, Phil Gersh, said the cause of death was cancer, for which March had been under treatment since his last motion picture appearance in Eugene O’Neill’s “The Iceman Cometh” two years ago.

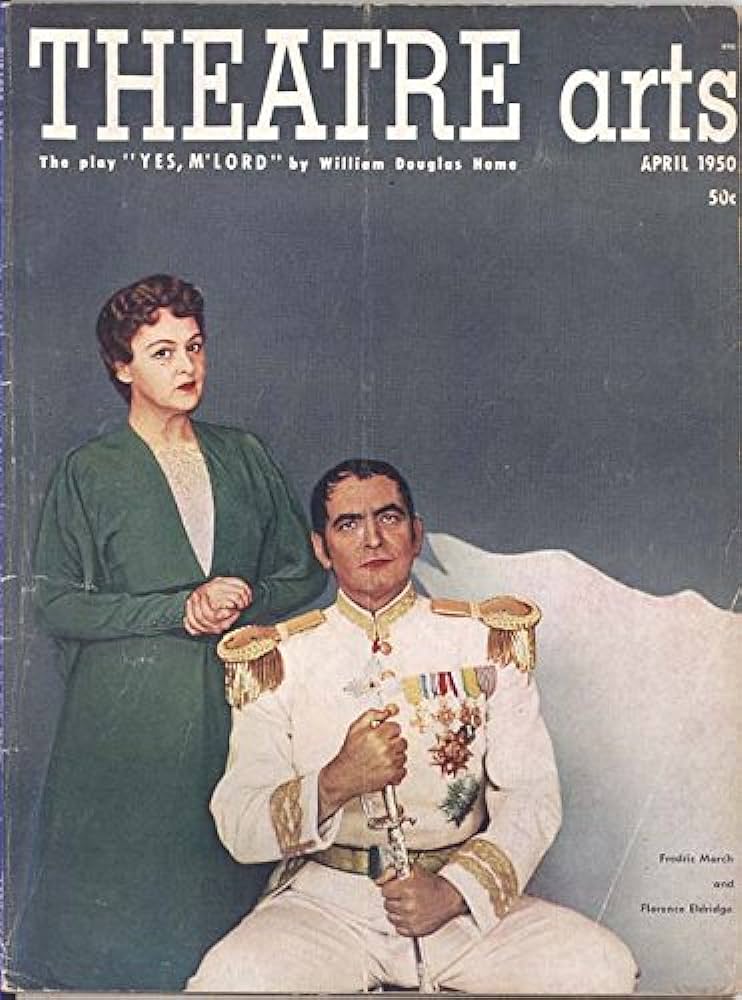

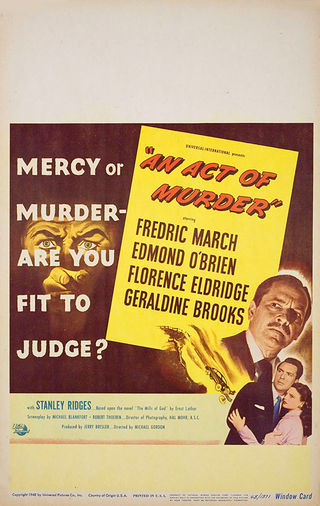

Florence Eldridge, March’s frequent stage and film costar and wife of 47 years, was at his bedside when he died.

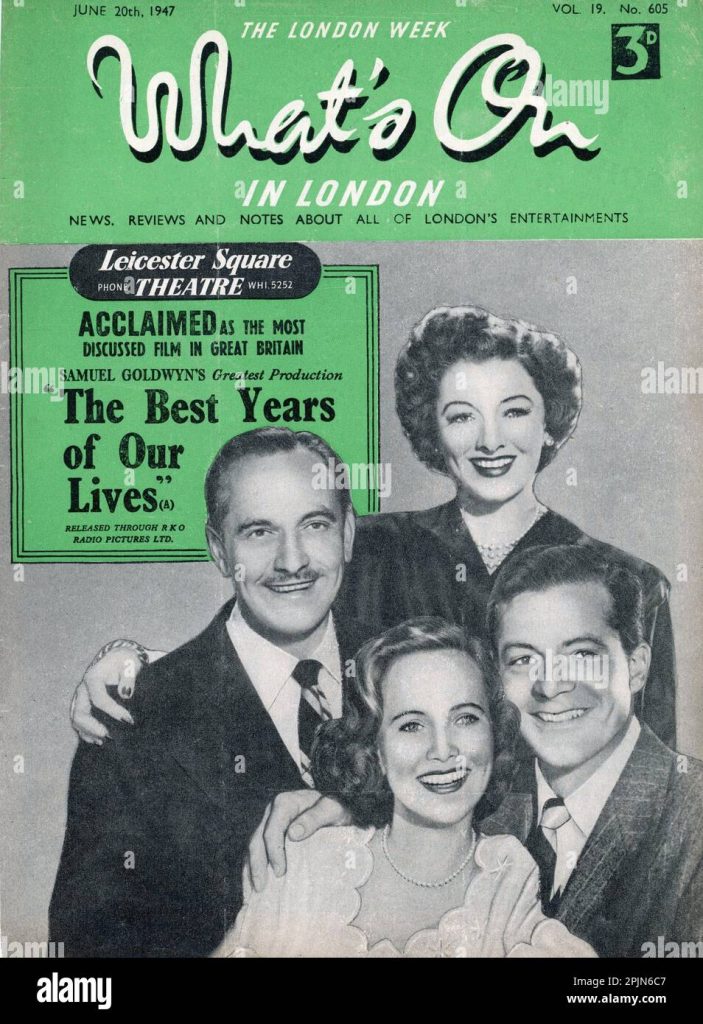

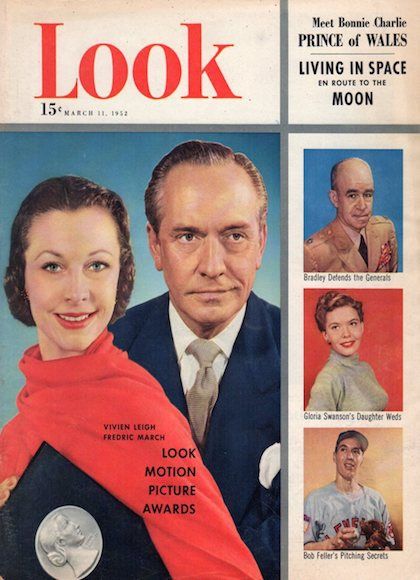

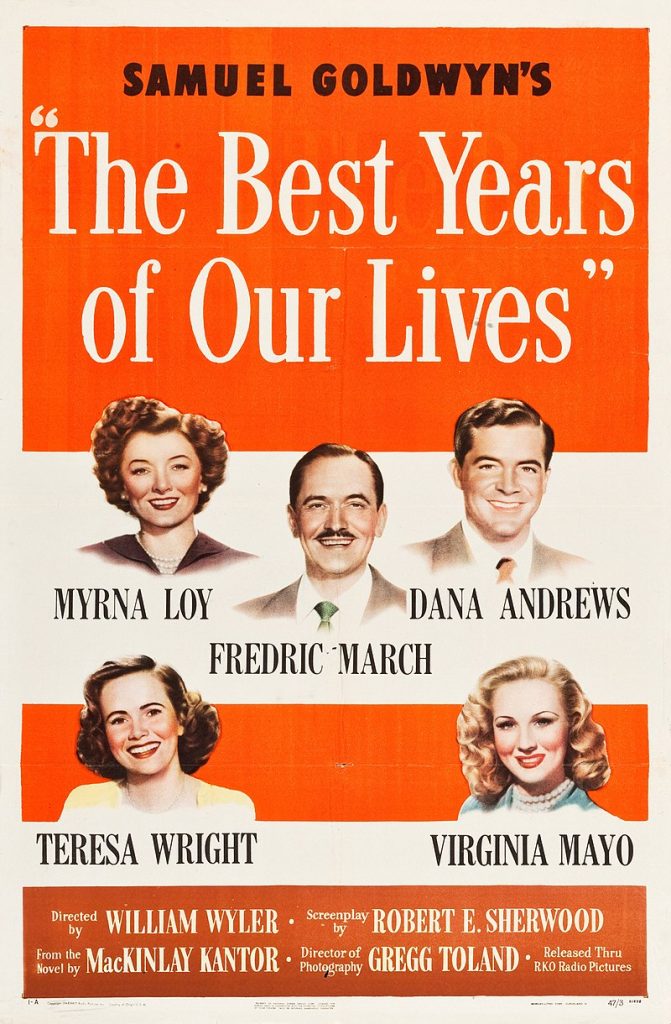

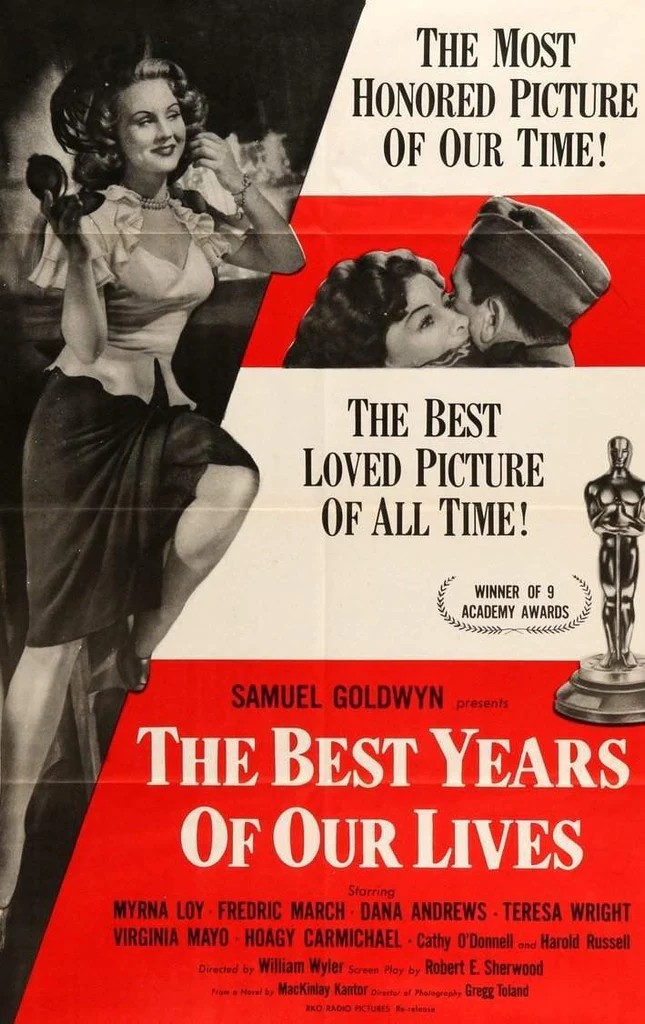

One of the world’s most respected and honored performers, March won Oscars for his 1932 title role in “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde,” splitting the award on a tie vote with Wallace Beery in “The Champ,” and again for his 1946 characterization of a middle-aged banker returning from World War II in “The Best Years of Our Lives.”

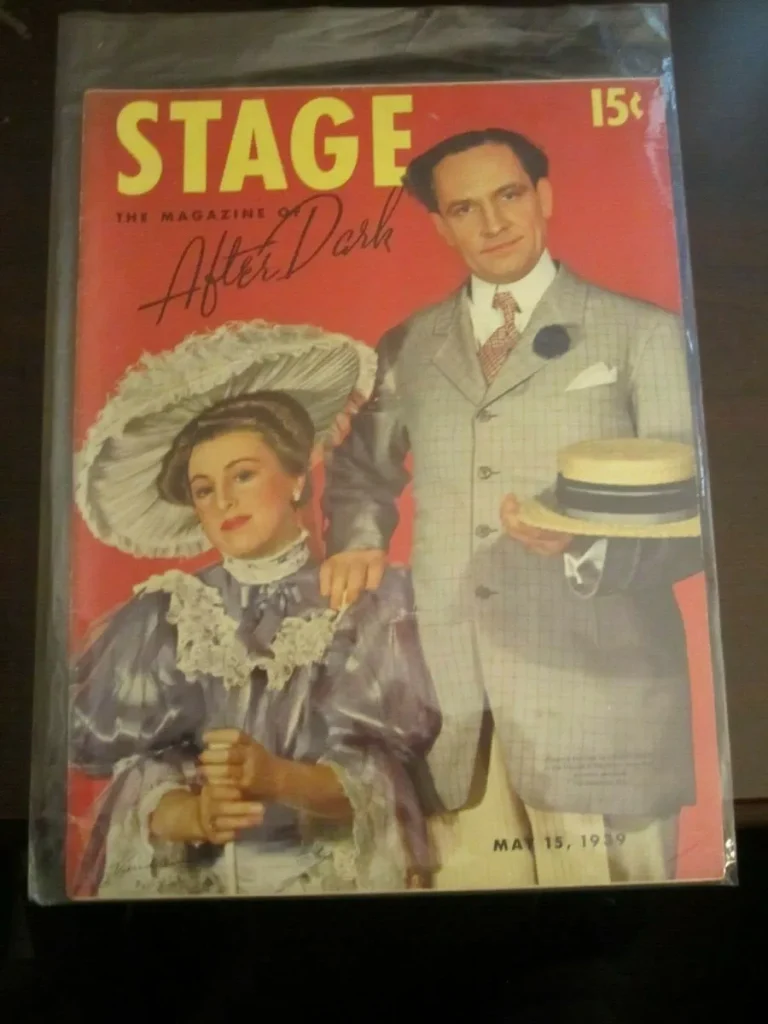

Although both he and Miss Eldridge had “officially” retired from acting more than two decades ago, March had been repeatedly lured back to the stage and films by roles he liked and wanted.

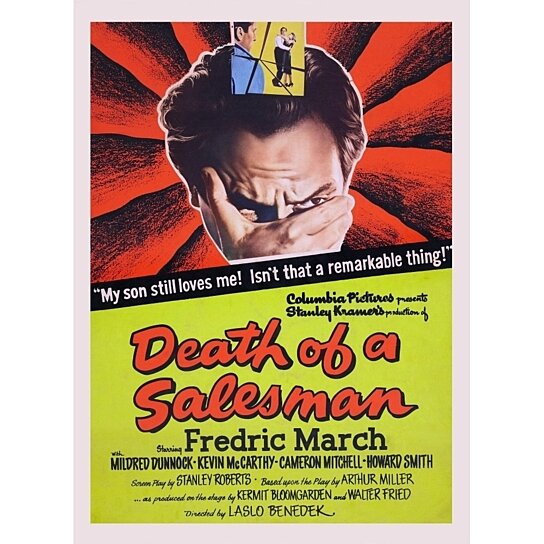

He won a Golden Globe award in 1952 for screen performance as the bemused and empty Willie Loman in the screen version of “Death of a Salesman.”

Born Frederick McIntyre Bickel, Aug. 31, 1897, in Racine, Wis., March was the son of a manufacturer and had always been intended for a banker’s career.

He was president of his graduating class at Winslow Grammer School in Racine and president of the senior class at Racine High School, where he graduated at 16. He had begun working as a part-time teller when World War I intervened.

Discharged in 1920 as a second lieutenant of artillery, March obtained his bachelor’s degree at the University of Wisconsin—where he was again elected senior class president—and was working at a New York City bank when an attack of appendicitis put him in bed for a month.

“It was,” he said later in life, “the luckiest illness of a lifetime. It gave me a while to think.”

What he thought about was acting. He had appeared in college and high school dramatics and had produced amateur shows in Racine since he was eight years old.

As soon as he was able to leave his bed he also left the banking profession (“You could say I returned to it briefly in ‘Best Years of Our Lives.’ ” he mused later) and began to haunt the New York theaters.

Again, luck was with him. In less than two months he had a job; he was part of a mob scene in the David Belasco production of “Deburau,” and by the end of the play’s run had become assistant stage manager and understudy to the star.

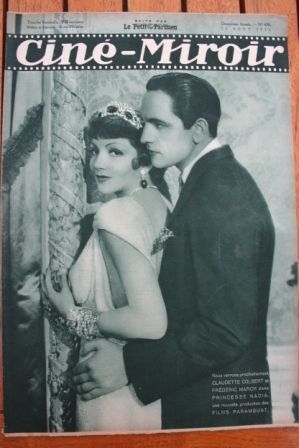

A handsome 6-footer with a winning smile, March found he could augment his slim acting income by posing for commercial artists and photographers, capitalizing a bit on his much-remarked resemblance to matinee idol John Barrymore.

“But I knew I wasn’t a trained actor,” he said. “And when I was given a chance to join a stock company in the West, I took it.”

The decision was fortunate in more than one way: he gained invaluable experience, performing everything from juvenile leads to old men—and he met Miss Eldridge. They were married in Mexico May 30, 1927.

Another lucky chance, according to March, was his decision to join the touring company of “The Royal Family” instead of accepting a somewhat more financially attractive Broadway offer the following year.

Los Angeles was on the show’s tour schedule, and March got his first film role, a bit part in the silent film “Paying The Piper,” and then another in “The Dummy.”

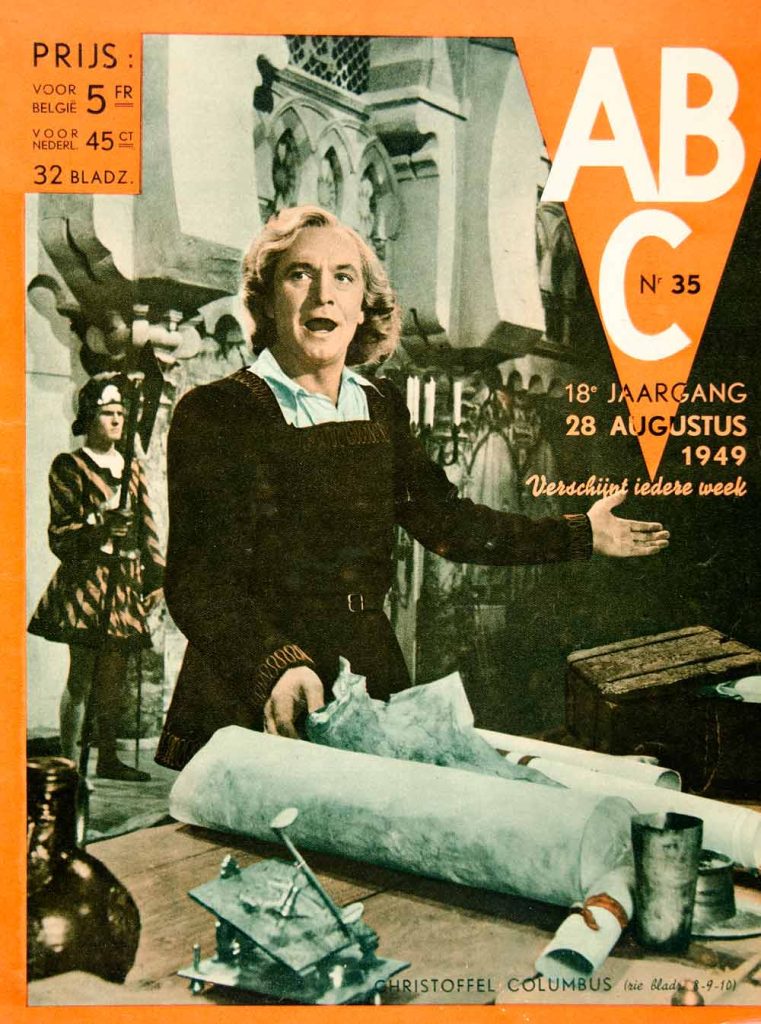

It was the advent of talking pictures, however, that finally brought him back to Hollywood in 1928 to begin his climb to international fame. He was in the film version of “The Royal Family” in 1928.

“I was lucky,” he recalled. “I got a five-year contract because someone had the notion that only stage actors could talk. It was the biggest break of all, maybe . . .”

In less than a decade, he was one of the top-earning actors of the era with an annual income of more than $300,000.

He also had made Hollywood history by turning down Darryl Zanuck when the studio chief proposed that he sign another five-year contract. March said he wanted to make his own deals from then on—and wanted to do some stage acting, too.

“When I left Zanuck,” he said, “he told me I couldn’t get anywhere without a big studio behind me. On the whole, though, I think I proved my point.”

He did. But not without a little trouble. He had co-financed his first post-studio production, a stage play that flopped because the juvenile lead came down with measles.

“That was Montgomery Clift,” March said. “He was a wonderful actor, even then. But, heaven help us, he was only about 15 or 16! When his mother called and said he was down with measles on opening night, we almost died. And the whole show did a week later.

“Monty had exposed everyone, and half the cast was sick.”

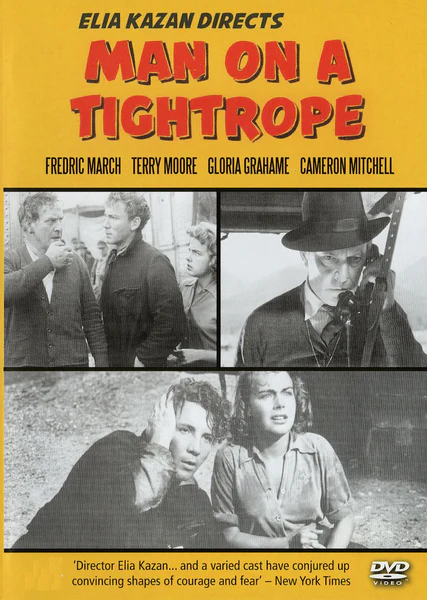

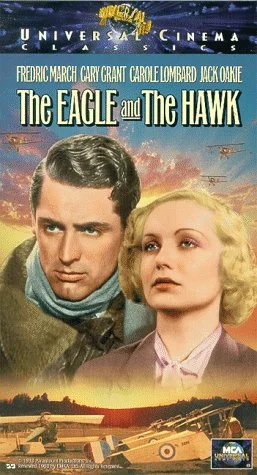

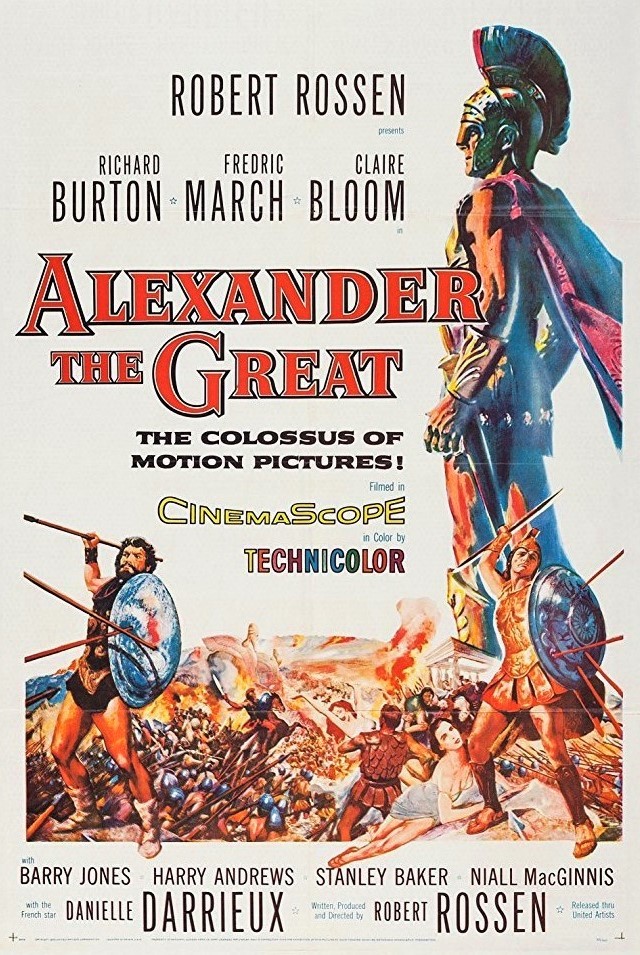

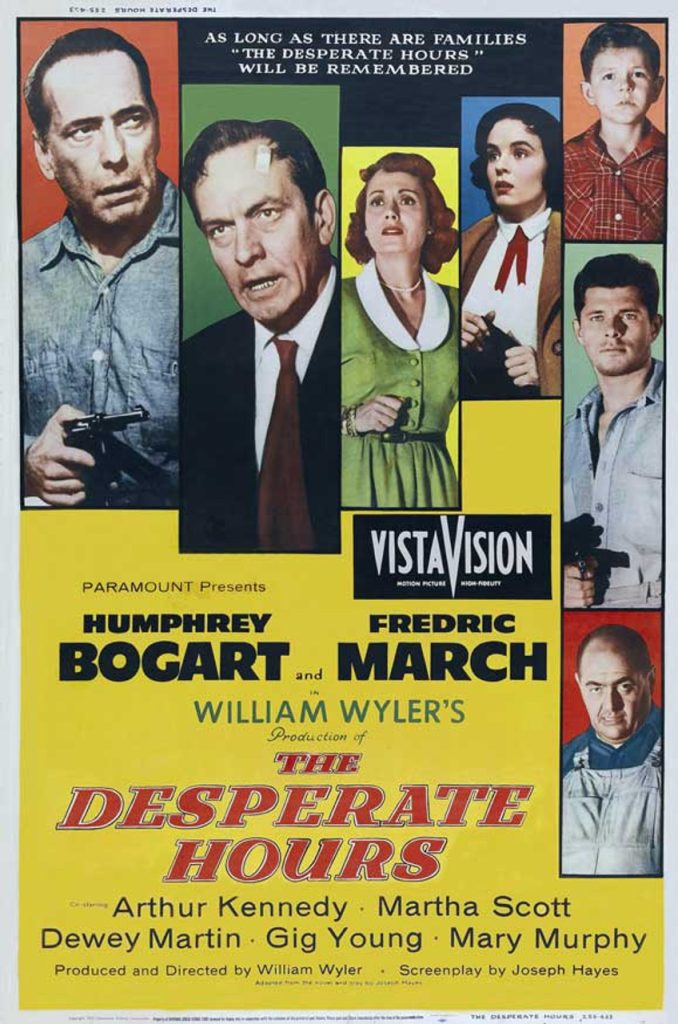

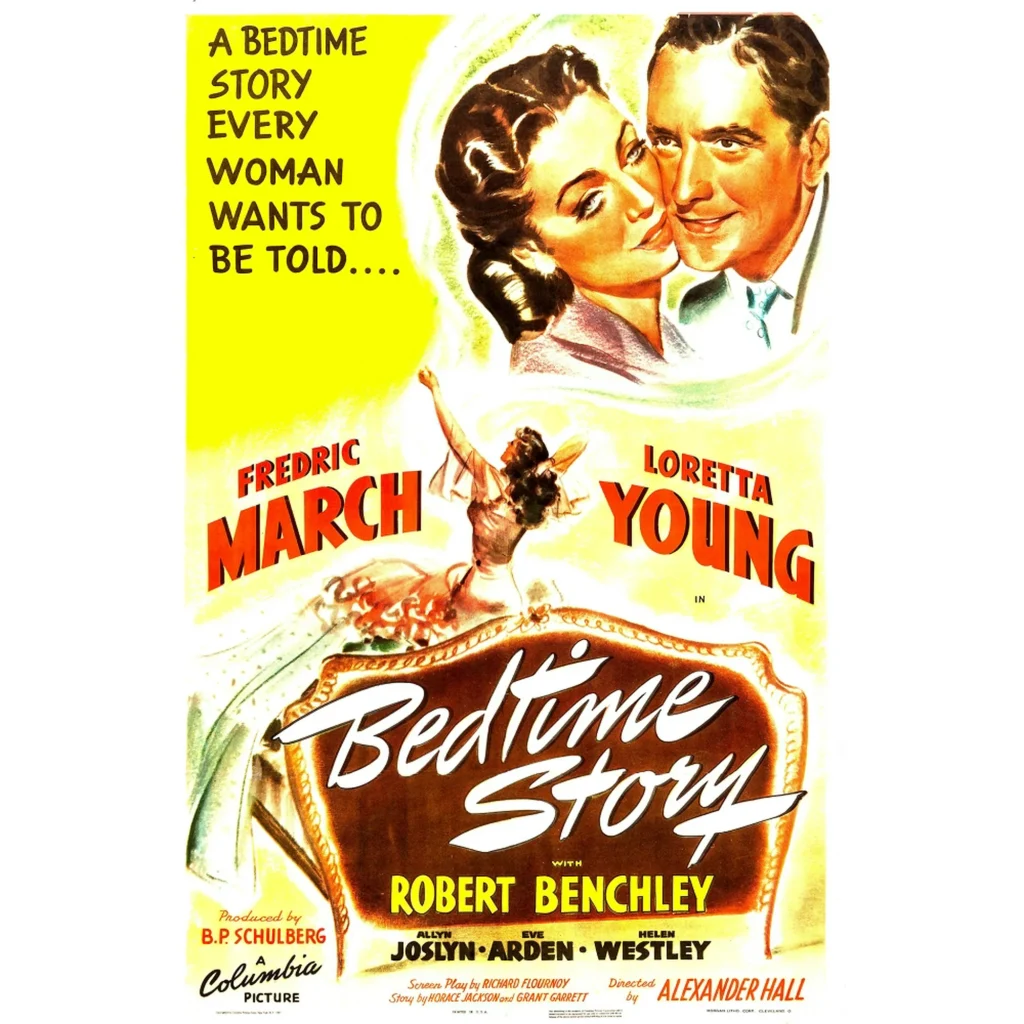

Undaunted, March returned to Hollywood for more starring roles, making an average of one picture a year and spending the rest of his time in stage work.

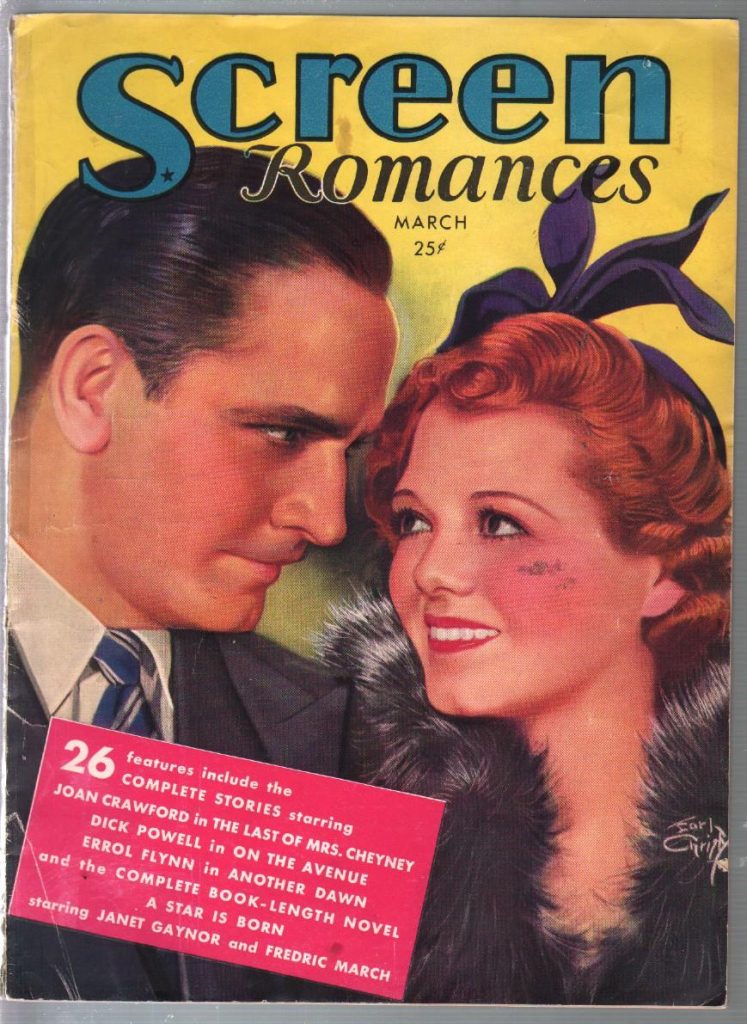

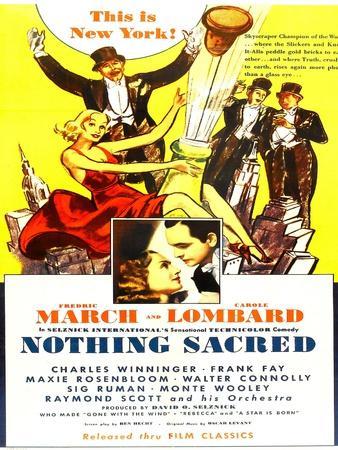

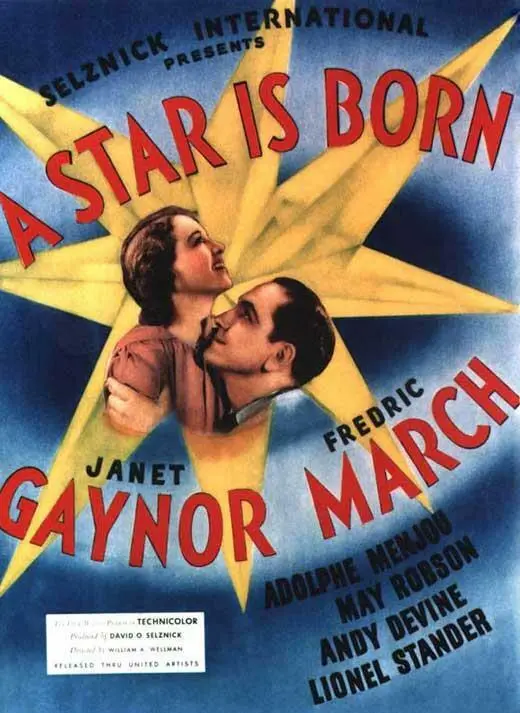

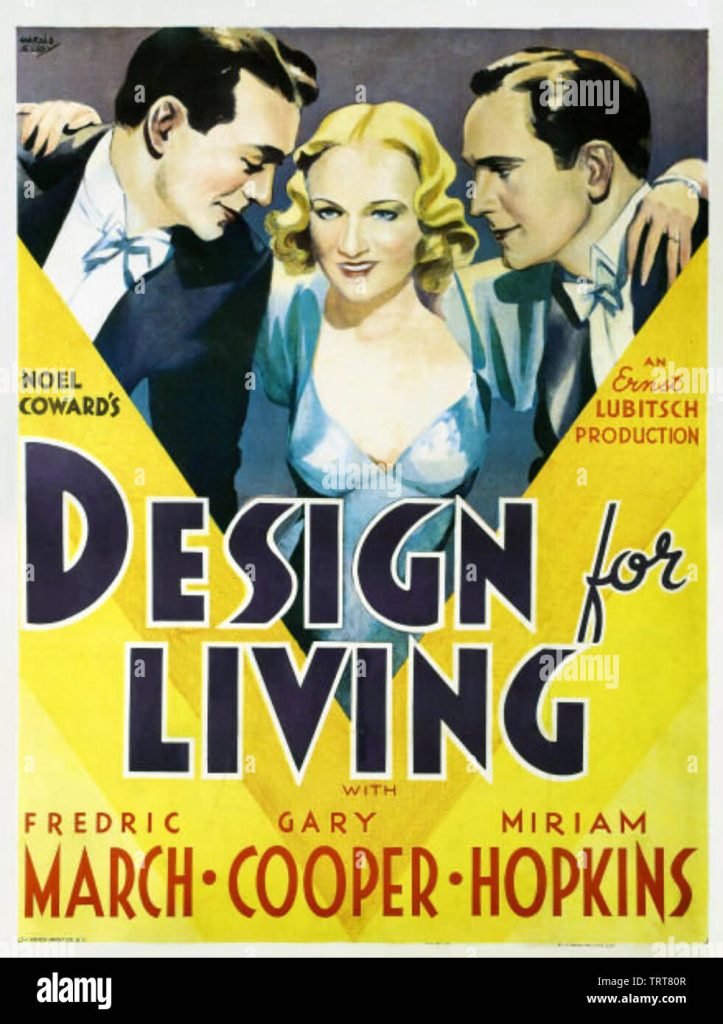

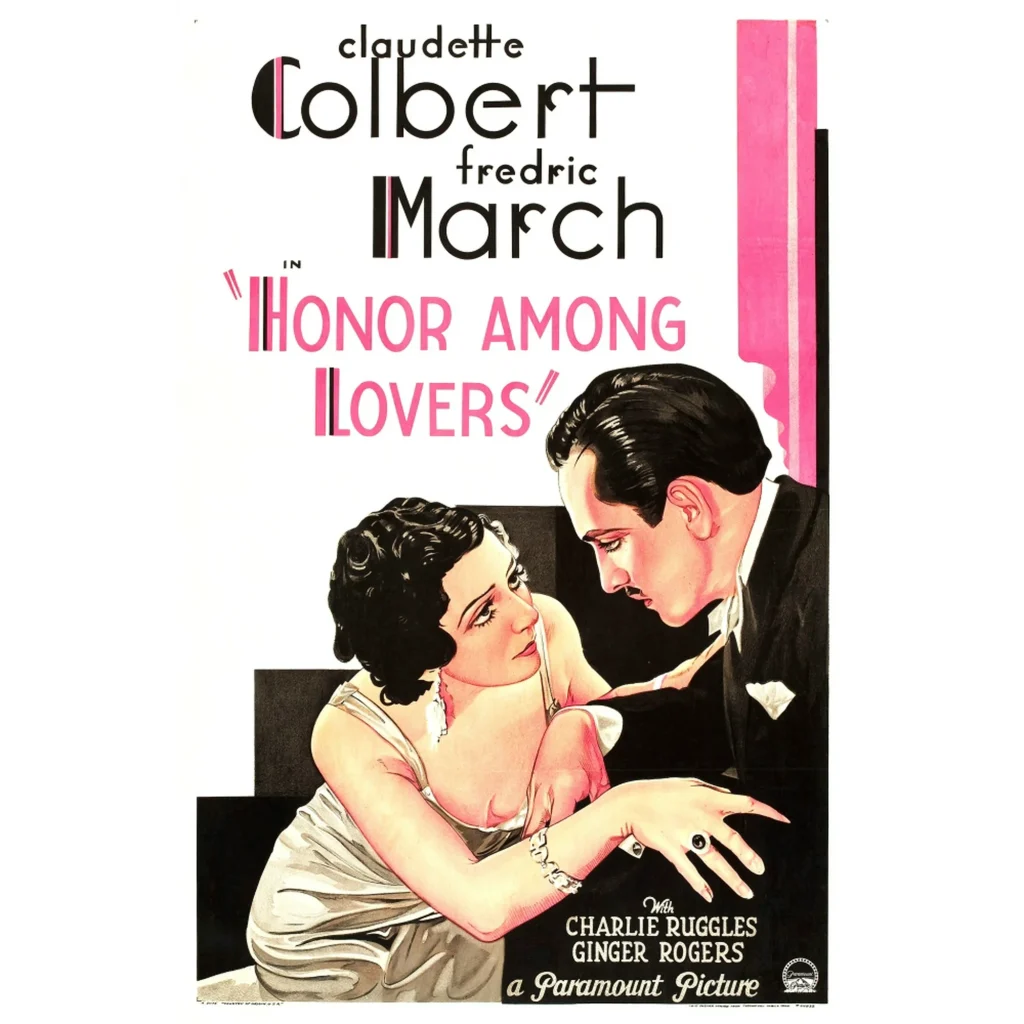

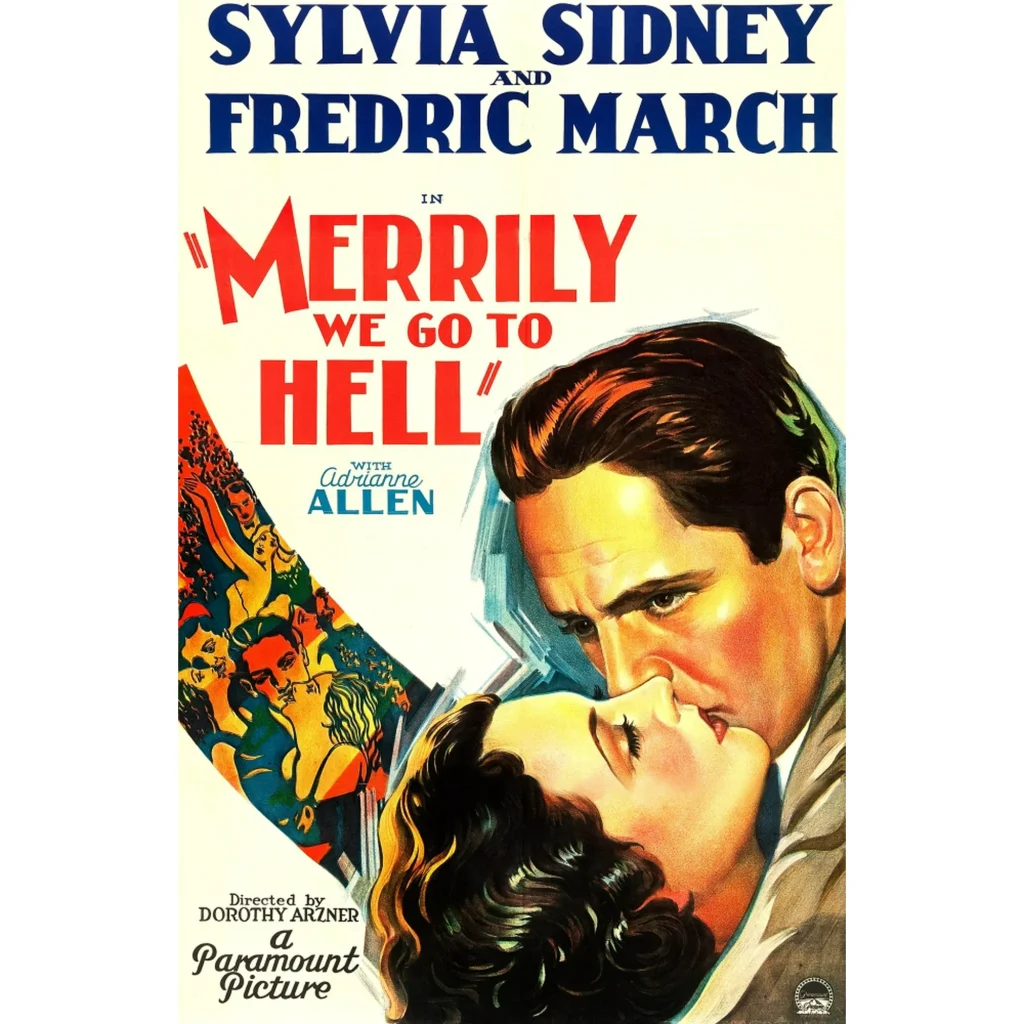

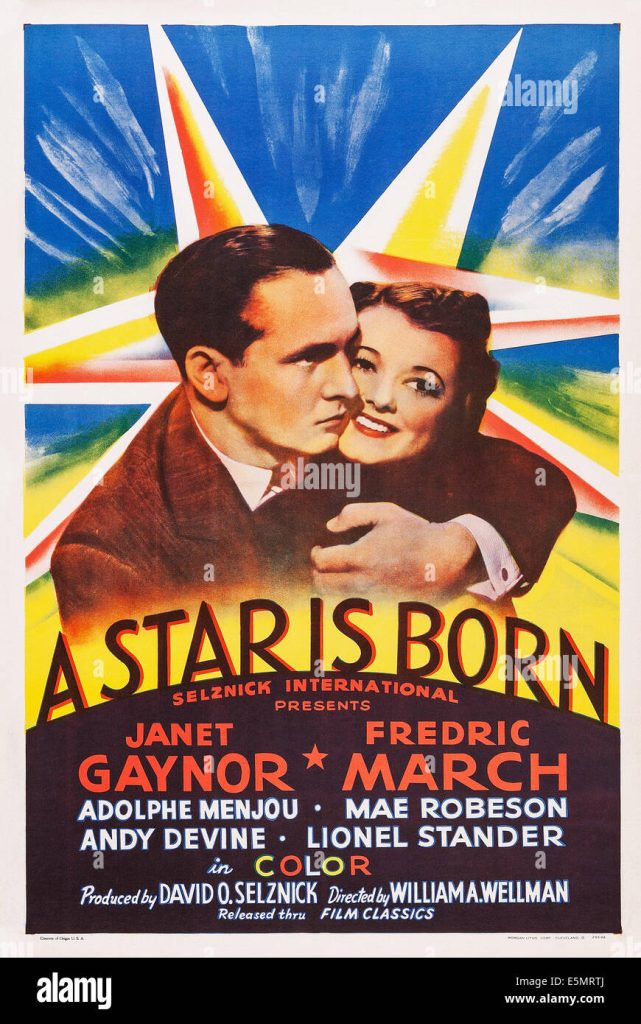

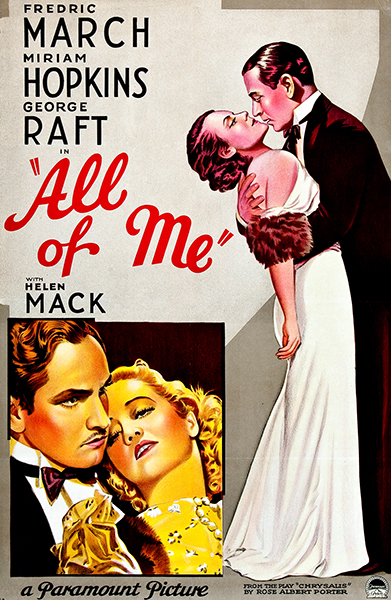

In films, he was originally confined to roles as suave leading men in romantic comedies. But he broke with tradition to win his first Oscar as the diabolical Mr. Hyde and defied standard casting techniques to play the alcoholic husband of Janet Gaynor in “A Star Is Born.”

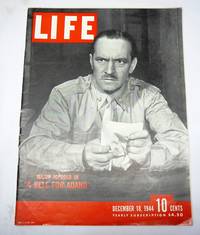

By the 1940s, his forte was more serious portrayals—such as the father in Thornton Wilder’s “The Skin of Our Teeth” (Again with Montgomery Clift) and stage roles in “Years Ago,” “A Bell for Adano,” and “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep.”

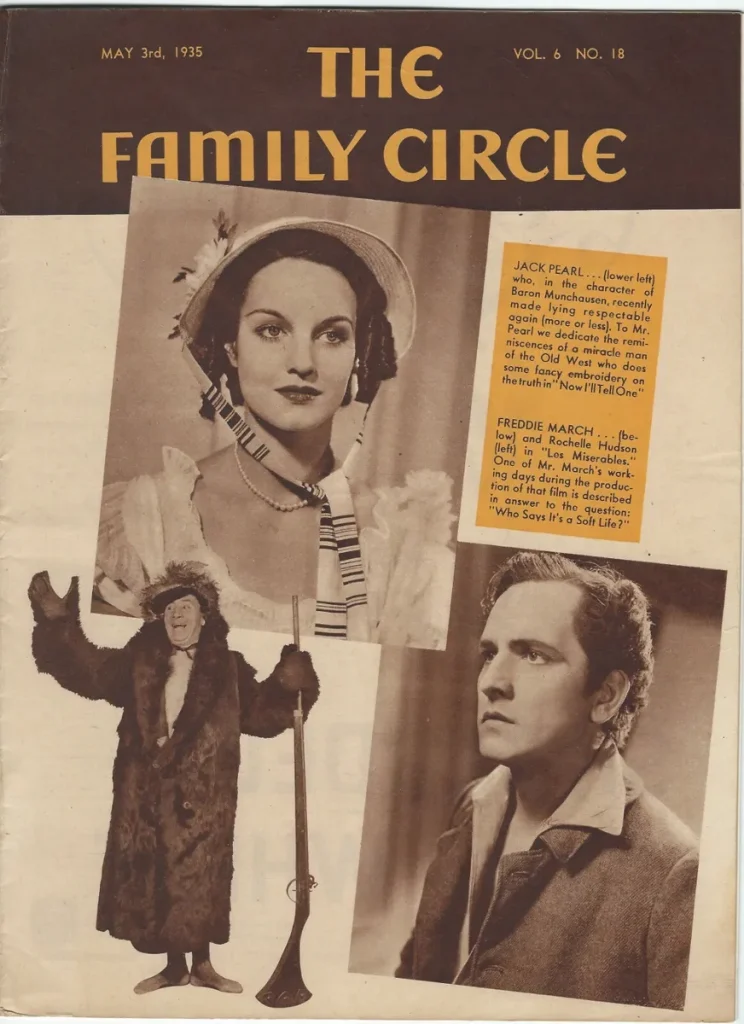

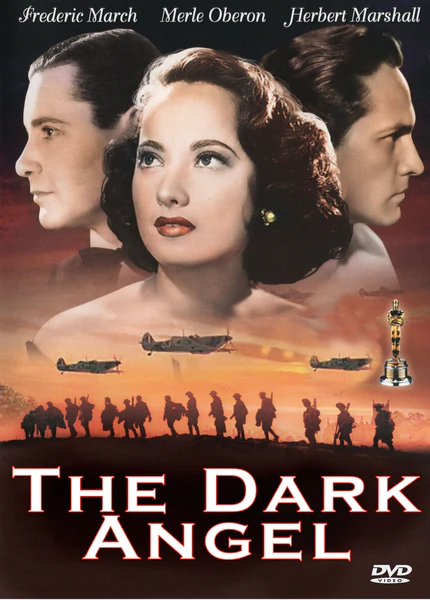

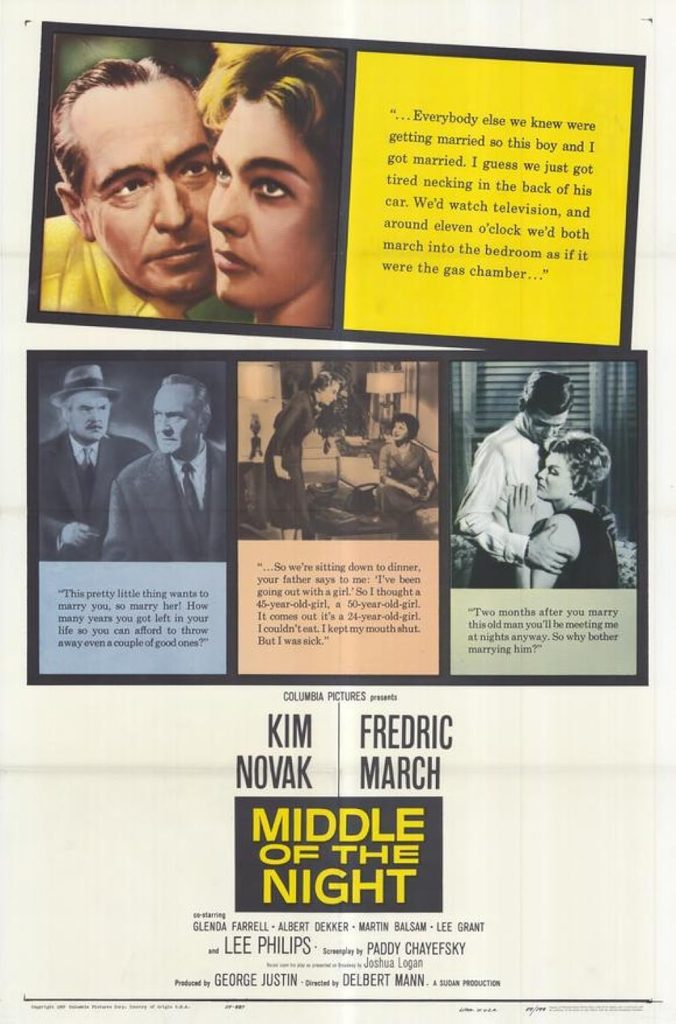

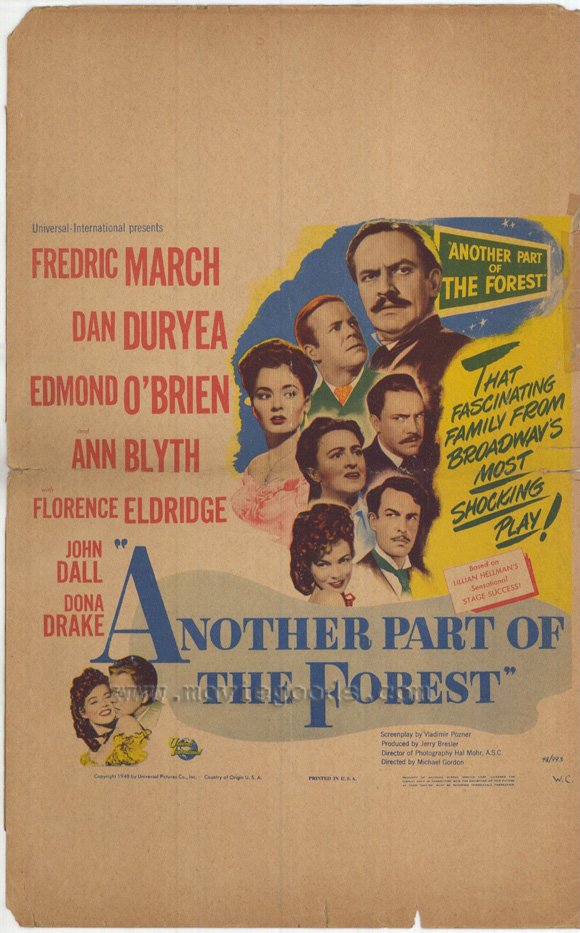

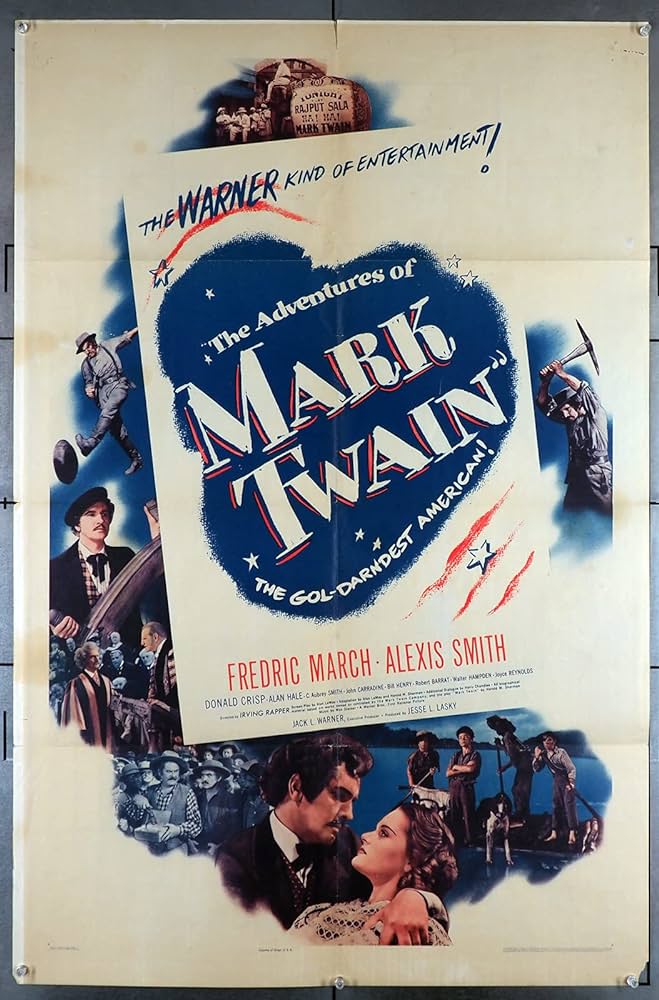

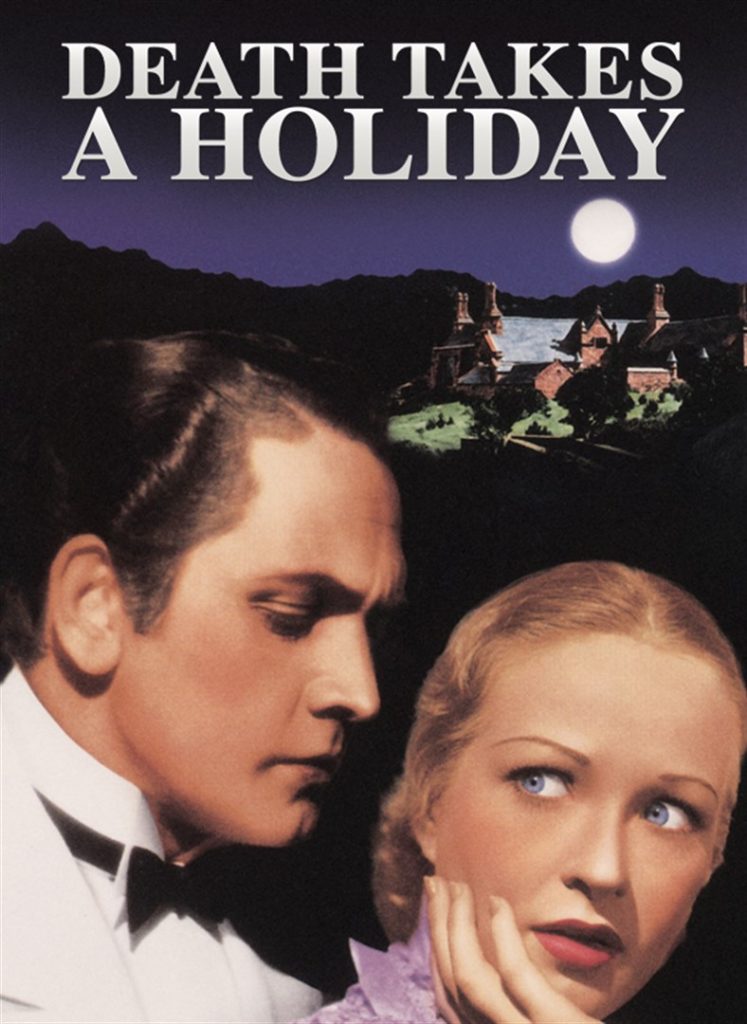

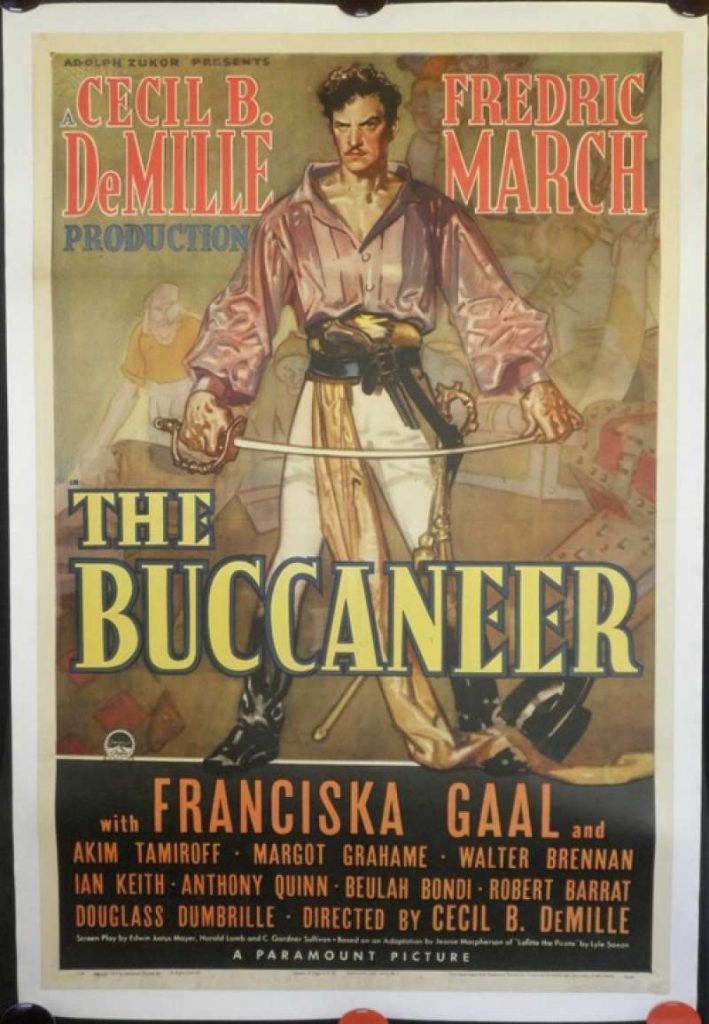

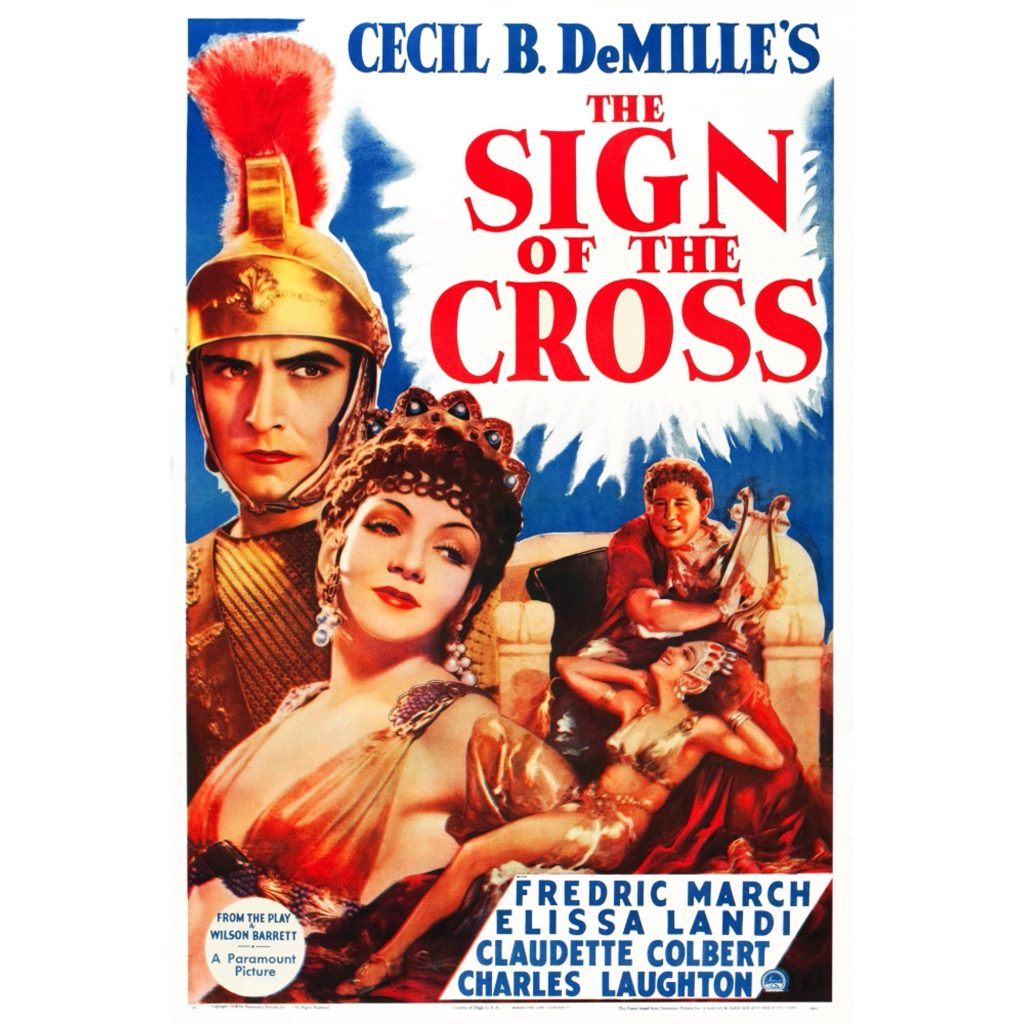

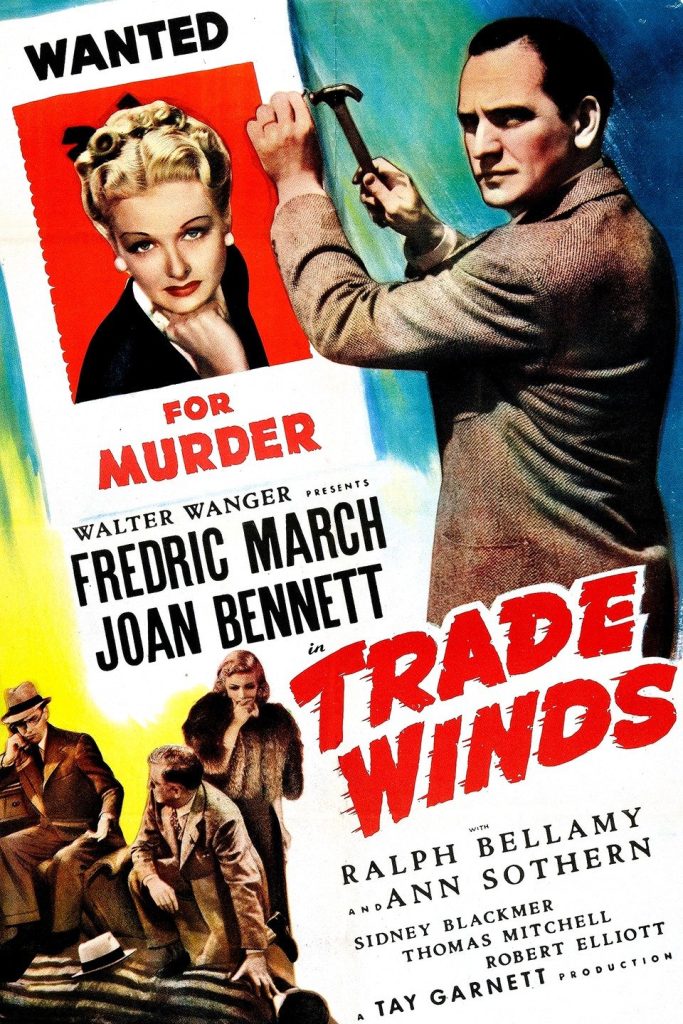

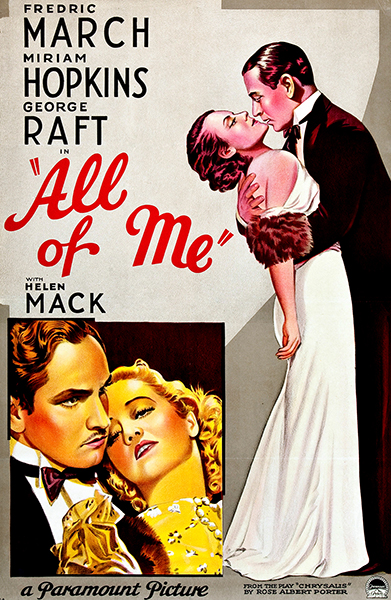

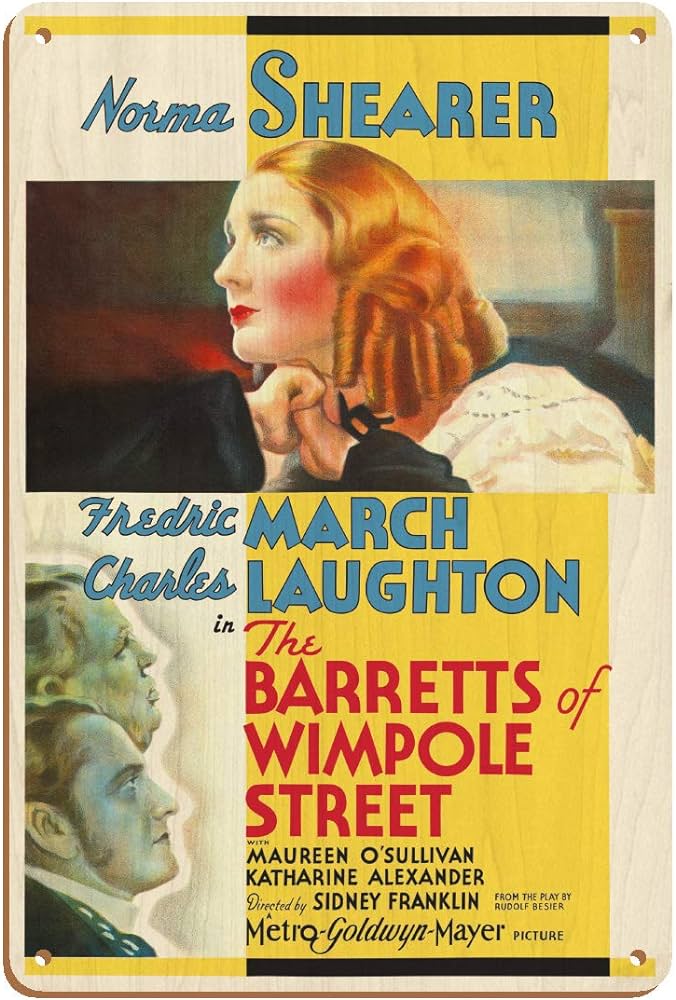

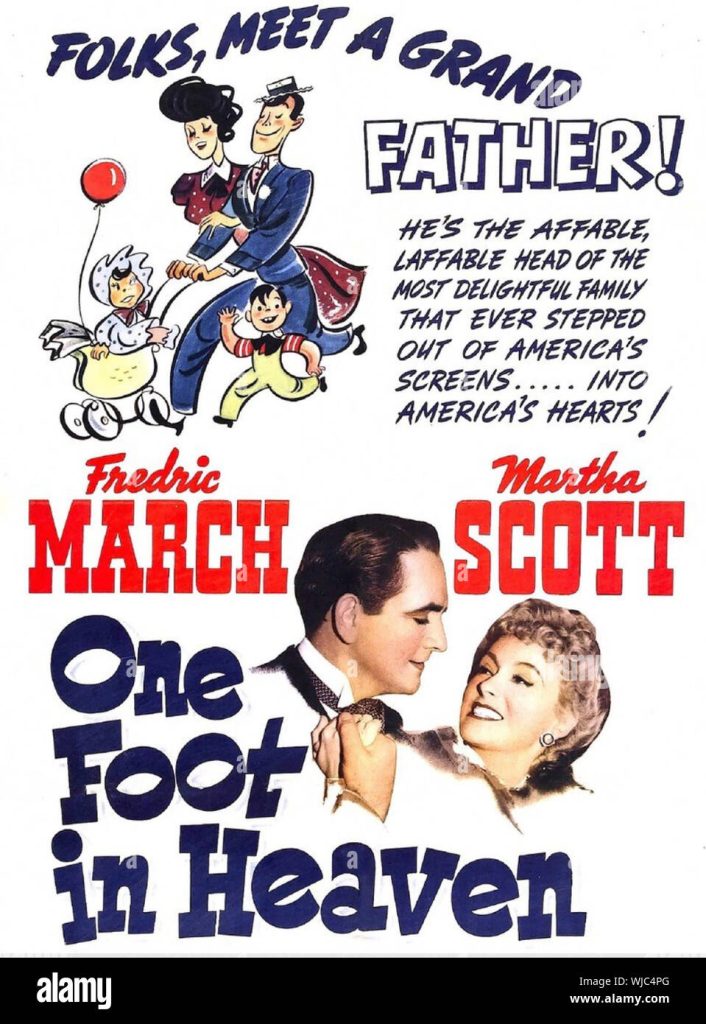

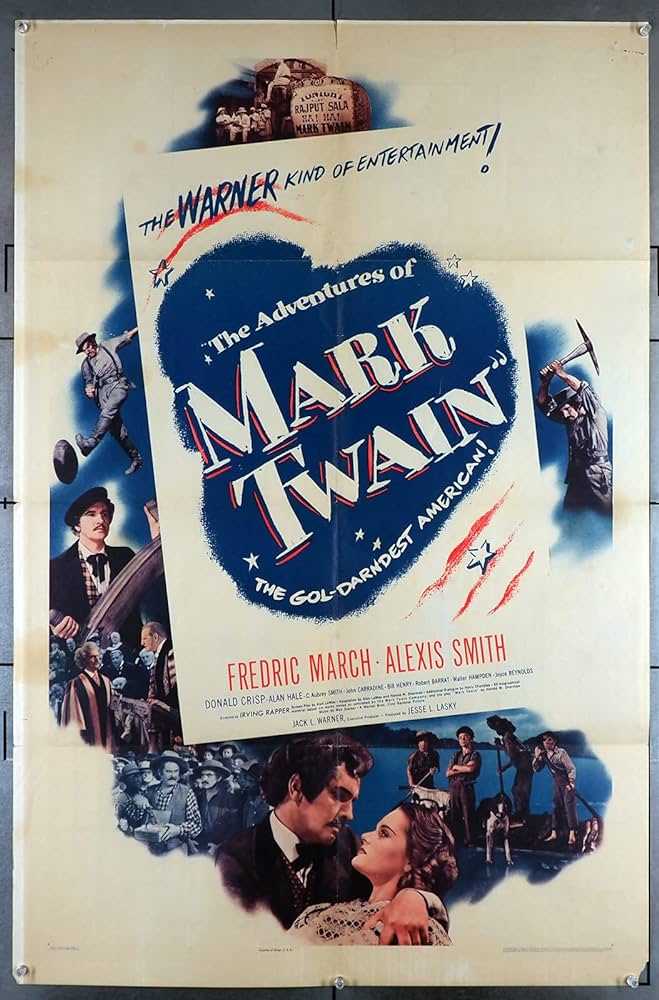

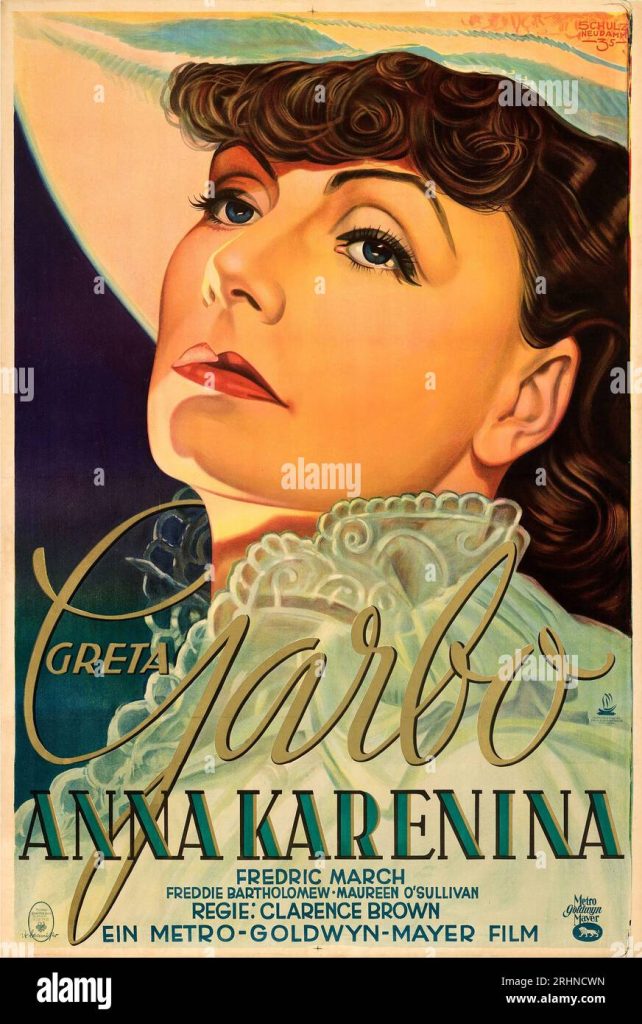

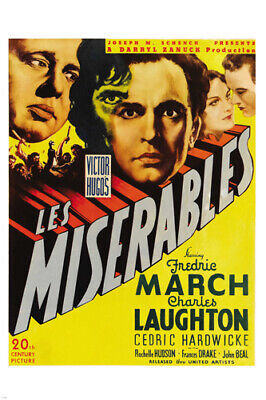

In addition, he appeared in such film successes as “The Sign of the Cross,” “Anthony Adverse,” “Les Miserables,” “The Barretts of Wimpole Street,” “Death Takes a Holiday,” “Tomorrow, the World!” “The Dark Angel,” “The Adventures of Mark Twain” and “The Middle of the Night.”

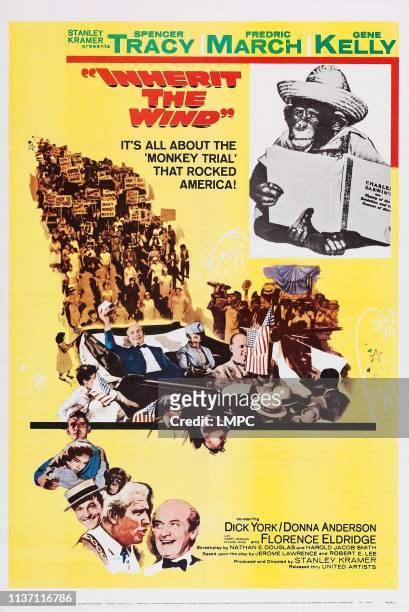

One of his favorite roles was as the aging and opinionated William Jennings Bryan opposite his old friend Spencer Tracy, in “Inherit the Wind.”

He also performed in television, moving to the new medium with a role as Scrooge in “A Christmas Carol,” one of the first big network color telecasts.

He recent years, despite his occasional emergences to work on stage or screen, March spent increasing time at his farm in New Milford, Conn., where he liked to perform the farm chores and clear land himself.

“I’m not really great with an ax,” he told a friend recently. “But I’m energetic.”

In addition to his wife, March leaves two adopted children, Penelope March Fantacci of Florence, Italy, and Anthony March of Texas.

March’s business manager said no funeral service is planned.

Florence Eldridge. Wikipedia.

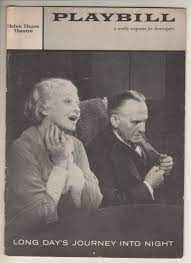

Florence Eldridge was born on September 5, 1901, in Brooklyn, New York – August 1, 1988, in Long Beach, California) was an American actress. She was nominated for the Tony Award for Best Lead Actress in Play in 1957 for her performance in Long Day’s Journey into Night.

The daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Charles J. McKechnie, Eldridge was born Florence McKechnie in Brooklyn. She attended public schools, including P.S. 85 and Girls’ High School.

Eldridge made her Broadway debut at age 17 as a chorus member of Rock-a-Bye Baby at the Astor Theatre. The reference book American Theatre: A Chronicle of Comedy and Drama, 1930-1969 noted, “In the 1920s she won major attention in such plays as The Cat and the Canary and Six Characters in Search of an Author.”[5]

In 1965, husband Fredric March and she did a world tour under the auspices of the U.S. State Department. Eldridge wrote that they were “experimenting to see if an acting couple doing excerpts from plays on a bare stage could reach and appeal to a worldwide audience.”[6]

On March 19, 1921, Eldridge married Howard Rumsey, who owned the Empire Theater and the Knickerbocker Players (both in Syracuse) and the Manhattan Players of Rochester. They were wed at her aunt’s home in Maplewood, New Jersey.

She was married to Fredric March from 1927 until his death in 1975, and appeared alongside him on stage and in films. Like her husband, she was a liberal Democrat.

She died of a heart attack aged 86. She was buried alongside her husband at the March Estate in New Milford, Connecticut.