Diana Rigg. TCM Overview.

TCM overview:

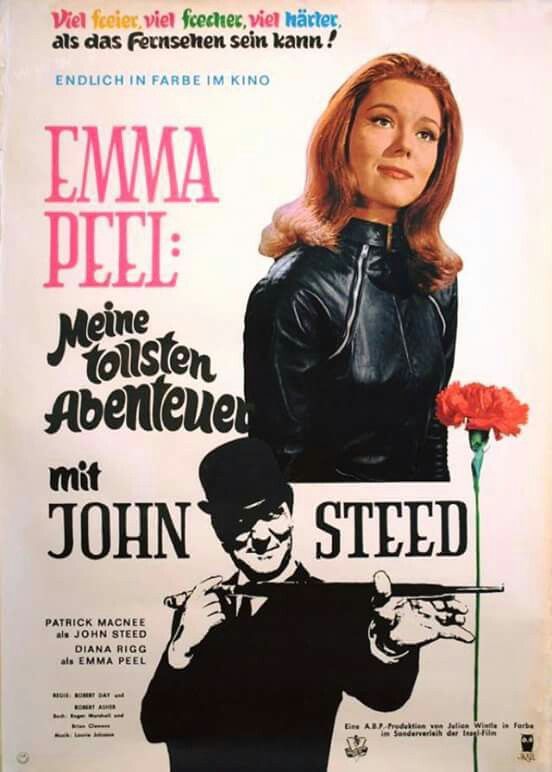

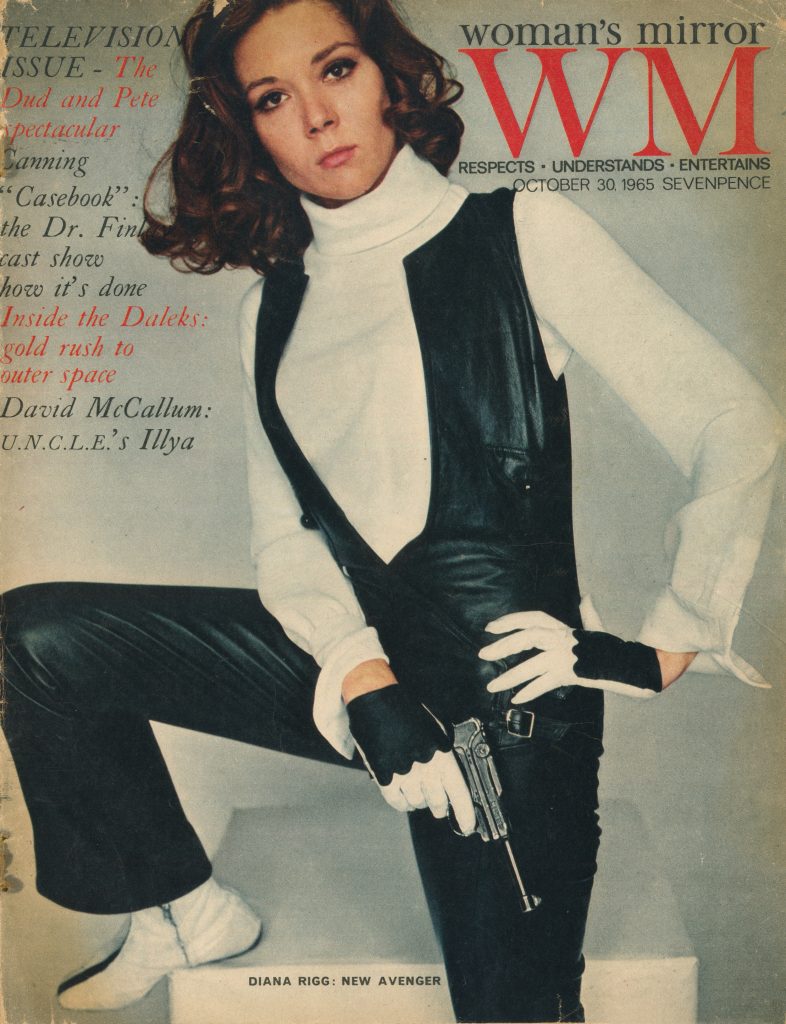

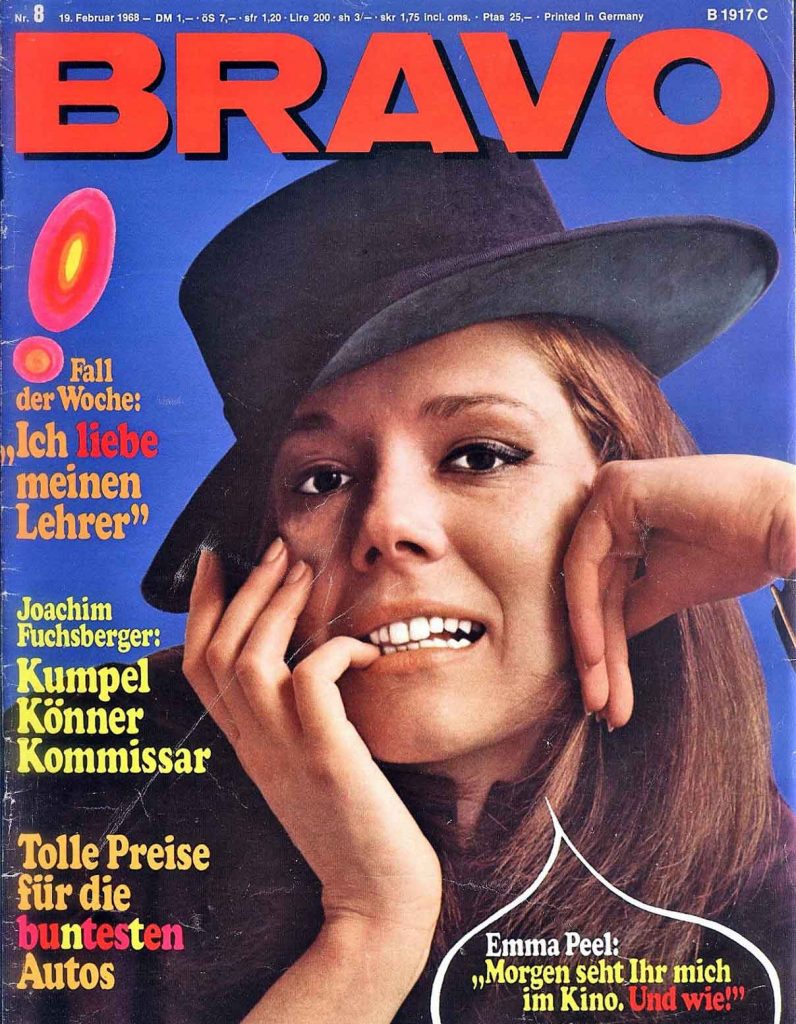

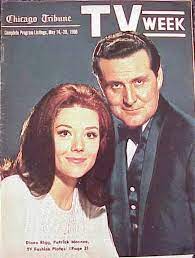

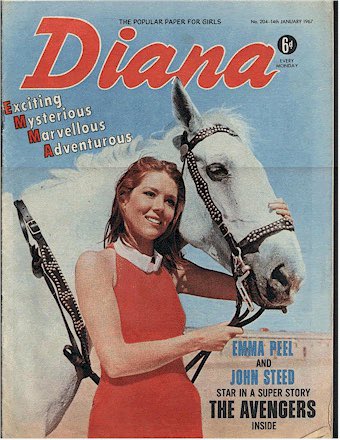

The poised, effortlessly versatile veteran of stage, film and television for over five decades, Dame Diana Rigg was a rara avis: a flawless interpreter of Shakespeare and other classical stage work, as well as a thinking man’s sex symbol as Mrs. Emma Peel, the catsuit-sporting crime fighter on “The Avengers” (ITV, 1961-69). Rigg’s cool beauty and knack for witty banter made her an idol among male viewers during the 1960s, but she struggled to overcome the character’s superhuman charms after leaving the show. She instead found lasting fame and respect on Broadway and television, where she netted Tony and Emmy awards as formidable figures like Medea and Mrs. Danvers in “Rebecca” (ITV, 1996). Though fondly remembered for “The Avengers” decades later, Rigg’s body of work made her one of the most accomplished and respected actresses in the business.

The Times obituary in 2020:

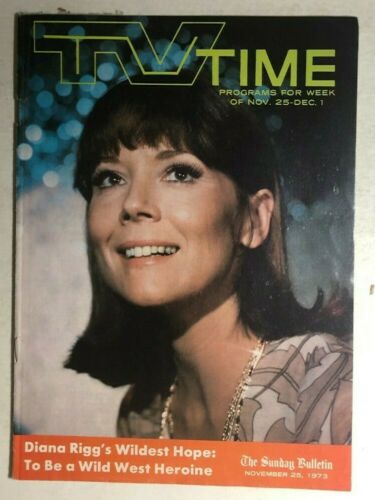

Becoming a sex symbol overnight was a shock to Diana Rigg, a classical actress with little experience of television. “I didn’t know how to handle it,” she recalled of the fame that came with playing Emma Peel, a secret agent in the Sixties television series The Avengers. As a dominatrix who sent the villains crashing to the ground with karate-chops and lethal kicks, she proved a perfect foil to the bowler-hatted John Steed, played by Patrick Macnee. That said, her shiny black leather catsuit was “a total nightmare”, taking 45 minutes to get unzipped and was “like struggling in and out of a wetsuit”.

Some of her fans were also a nightmare. On one occasion she had to hide from them in the lavatory at the Motor Show, and in Germany the police resorted to holding them back with batons. “I kept all the unopened fan mail in the boot of my car because I didn’t know how to respond and thought it was rude to throw it away,” she said. “Then my mother became my secretary and replied to the really inappropriate ones saying, ‘My daughter’s far too old for you. Go take a cold shower!’ ”

Rigg’s on-screen verbal wit may have been as quick as her physical prowess, yet she was no different off screen, holding out after her first series for a pay rise from £150 a week (about £3,500 today) to £450 (about £10,500). “Not one woman in the industry supported me when I demanded more money after finding out the cameraman on The Avengers was paid a lot more than me,” she told The Guardian last year. “I was painted as this mercenary creature by the press when all I wanted was equality.”https://imasdk.googleapis.com/js/core/bridge3.450.0_en.html#goog_540870088Play VideoDiana Rigg’s best roles

Yet she was far from the unfeeling battle axe that some made her out to be. “When I appeared nude in a play on Broadway in the early Seventies, a nasty little critic said I was built like a brick mausoleum with insufficient flying buttresses,” she said, recalling how devastated she was by the comment. “He should have seen me after the menopause, there was no shortfall then.”

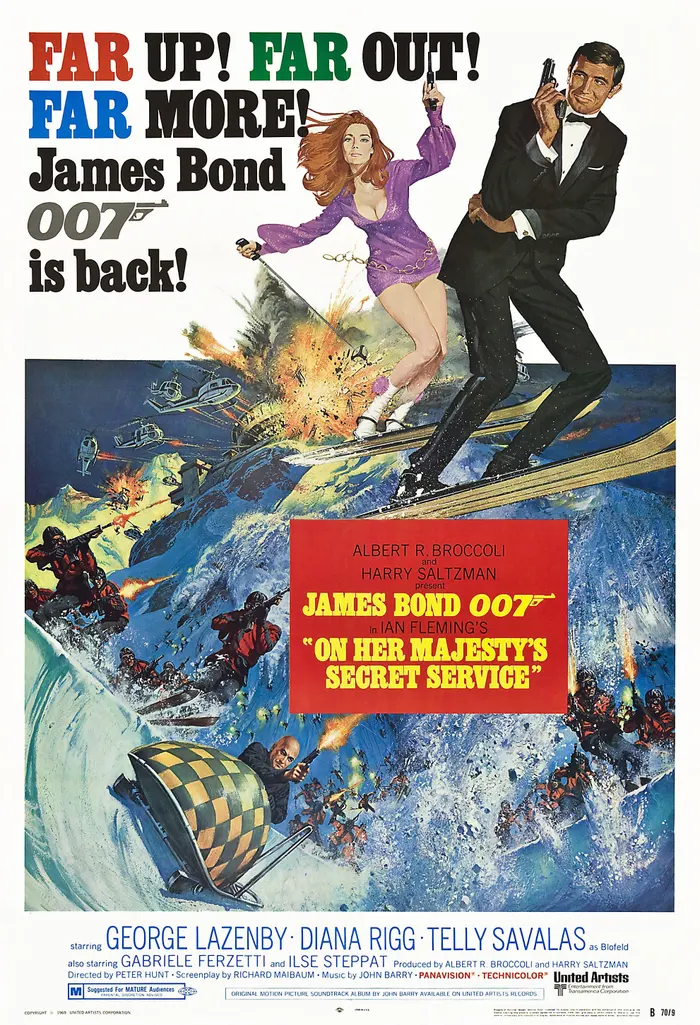

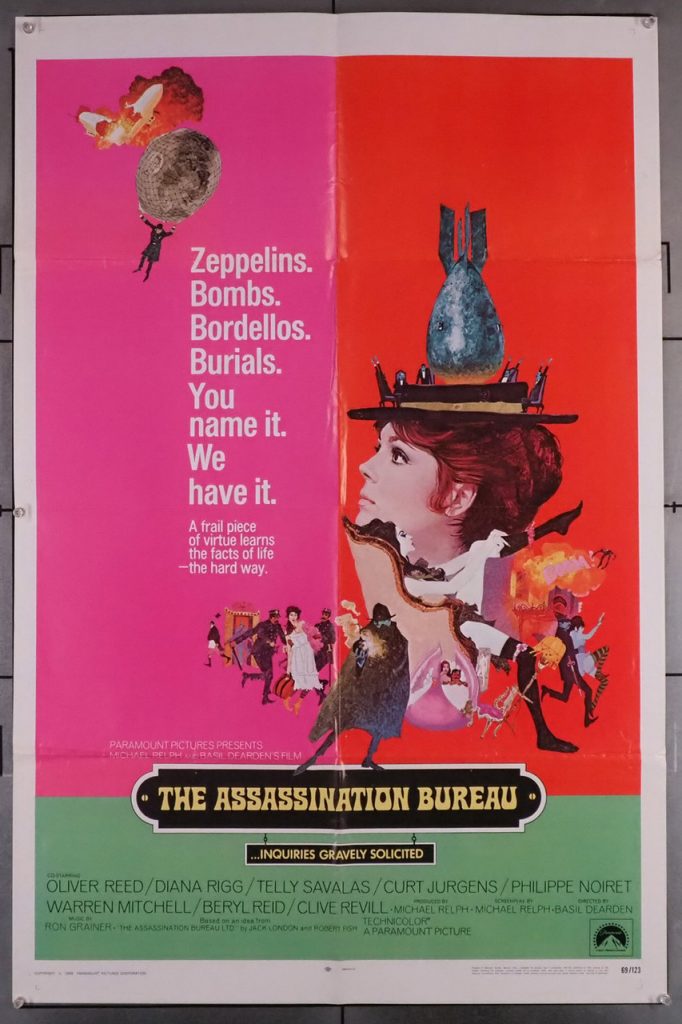

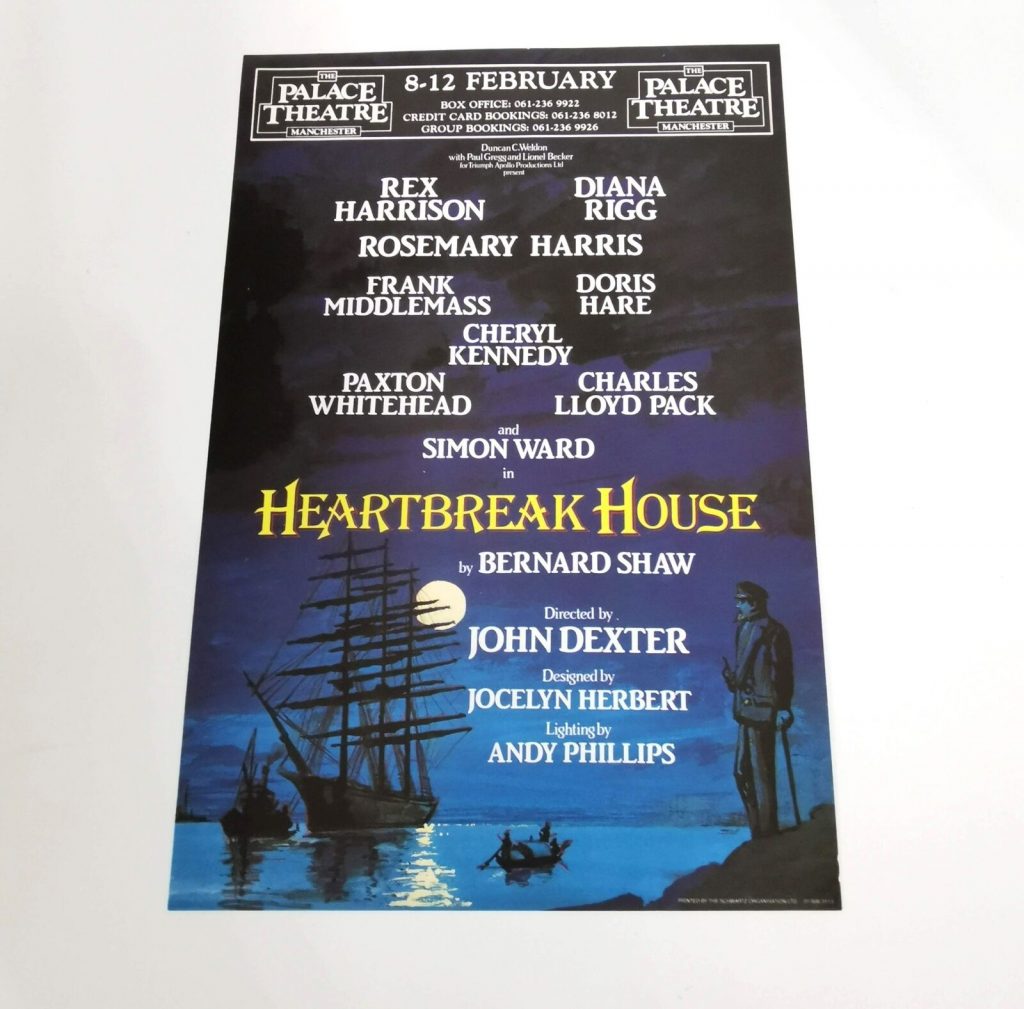

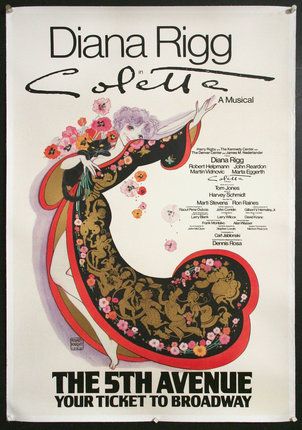

Although Rigg played an eclectic range of screen roles, including Tracy, the only character to marry James Bond (George Lazenby), in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), her heart lay in the theatre, where she got better and better as age gave her performances increasing depth and maturity. Tom Stoppard’s Jumpersat the National Theatre gave her intricate wordplay and nudity of a more playful kind as Dotty, the wayward wife of Michael Hordern’s troubled philosopher. She then began taking on great tragic heroines, from Lady Macbeth to Brecht’s Mother Courage and Racine’s Phaedra.

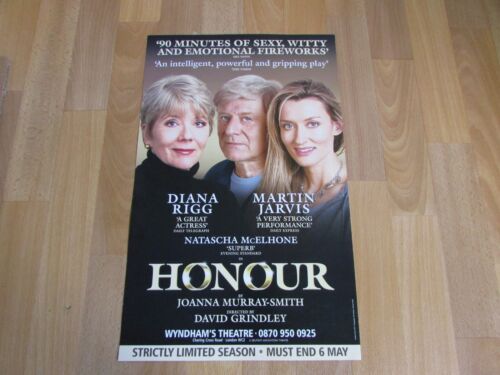

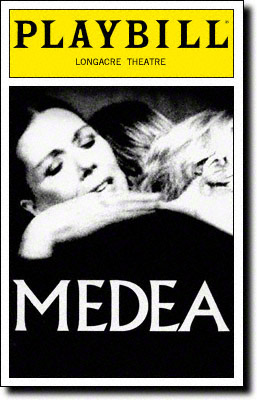

She regarded her Medea, first tackled in 1992 when she was in her mid-fifties, as her supreme achievement. The performance was forged in the modest environment of the Almeida Theatre in Islington, north London, and the cast, who rehearsed in a draughty church hall, were paid the Equity minimum wage. Even after a chorus of critical acclaim, the production struggled to find a West End theatre, but it eventually did and from there went on to New York, with more plaudits for Rigg and a Tony award.

Yet Rigg was never one to take herself or her profession too seriously. Although she served both with intense dedication and great skill, she happily camped it up with Morecambe and Wise, playing Nell Gwyn to Ernie Wise’s Samuel Pepys and Eric Morecambe’s King Charles II on their 1975 Christmas show.

Diana Rigg starred opposite George Lazenby in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service as Tracy, the only character to marry BondKOBAL COLLECTION

Enid Diana Elizabeth Rigg was born in Doncaster in 1938, the younger of two children of Louis Rigg, a railway engineer whom she lovingly recalled reading to her as a small child, and his wife, Beryl (née Helliwell). Her elder brother, Hugh, became a squadron leader in the RAF. She was two months old when her father’s work took the family to Bikaner, in northwest India, and she grew up speaking Hindi as a second language.

At seven she was sent to a boarding school in Buckinghamshire, which she hated, and later attended Fulneck School in Pudsey, West Yorkshire. “Yorkshire really formed my character,” she said. “I get straight to the point and say what I feel. I can’t help it, it’s genetic.” Yet the school discouraged any thoughts of a stage career. “I might as well have said I wanted to go on the game when I told the headmistress I wanted to be an actress,” she recalled. However, she was encouraged by her elocution teacher and at 16 auditioned successfully for the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

Her first stage appearance was in a Rada production of The Caucasian Chalk Circle at the Theatre Royal, York, in 1957. Two years later, after spells modelling clothes and in repertory, she joined the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon, soon to become the Royal Shakespeare Company under Peter Hall. “I was, literally, a spear-carrier,” she said. “I had a walk-on part and watched the likes of Dame Edith Evans and Laurence Olivier who were in the company. What a training.” It was there that she took up playing bridge while waiting in the wings, recalling: “I can’t tell you how many entrances I missed because of it.”

She graduated to the middle-ranking Shakespearean roles, bringing to them a force and intelligence that came partly from her voice but also a physical presence, a natural beauty enhanced with large, expressive eyes. The 1962 Stratford season was particularly busy. She was Helena in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Bianca in The Taming of the Shrew, Lady Macduff in Macbeth, Adriana in The Comedy of Errors and, most notably, Cordelia in Peter Brook’s production of King Lear, with Paul Scofield as the king. She repeated Cordelia and Adriana for a British Council tour of Europe, the Soviet Union and the US, making her New York debut in 1964.

Then came the abrupt change of career to ITV’s stylish adventure series The Avengers, which, having established its off-beat, sometimes surreal humour, needed a new leading lady after Honor Blackman’s departure for the cinema. Rigg left in 1968, having done some 50 episodes and fearing that she would be typecast. Yet Emma Peel was not forgotten and on the strength of it Rigg was voted the sexiest television star of all time by an American magazine in 1999.

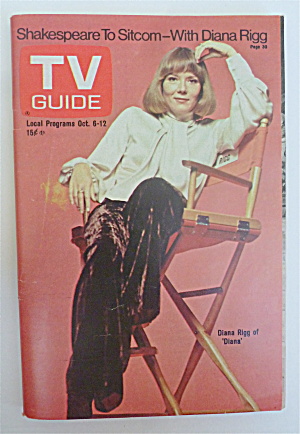

Thereafter her television appearances were spasmodic, though invariably watchable. In an attempt to break from The Avengers she accepted an invitation from NBC in the US to star in her own sitcom, Diana, playing an English divorcée in New York. The show was too bland to make much of an impact, but she was happier in a British sketch series, Three Piece Suite (1977), the material for which was supplied by the cream of television comedy writers including Jilly Cooper, Alan Coren and Keith Waterhouse.

During the Sixties Rigg enjoyed a bohemian and sexually liberated existence, vowing that she would never marry. For eight years she lived with the film producer Philip Saville, “the first man I really loved”. However, in 1973 she married Menachem Gueffen, an Israeli painter, but the relationship quickly foundered. “Menachem and I should never have got married,” she told the Daily Mirror amid reports of belongings being thrown from windows. “I’m extremely angry with myself for making such an idiotic mistake.”

Her second marriage in 1982 was to Archibald Stirling, a Scottish landowner, and cast her for a time as a conventional lady of the manor, but it was dissolved after he had an affair with the actress Joely Richardson. Rigg is survived by their daughter, Rachael Stirling, an actress who starred in Tipping the Velvet and with whom Rigg appeared in a 2013 episode of Doctor Who entitled The CrimsonHorror.

On Her Majesty’s Secret ServiceALAMY

Her later work included Victoria, in which she played the Duchess of Buccleuch, the role of Lady Olenna Tyrell in Game of Thrones, a television adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, for which she won an Emmy award as Mrs Danvers, and the BBC mini-series Mother Love, which brought her a Bafta award for best actress as Helena Vesey, an obsessive and controlling mother.

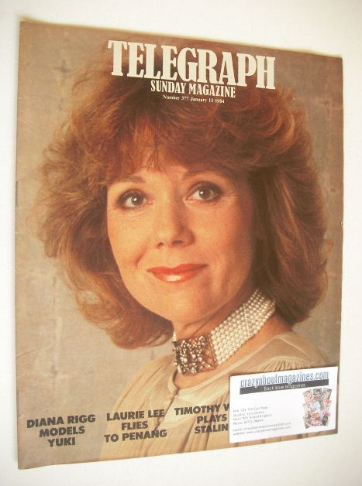

Although Rigg had not been to university, she had some compensation in her early sixties when she became visiting professor of contemporary theatre at Oxford University and was elected chancellor of Stirling University. She edited a collection of hostile theatre reviews entitled No Turn Unstoned (1982) and an anthology of English country lyric poetry, So to the Land (1994).

Rigg was a tall, broad-shouldered woman with a straight spine and a thick bob of hair, retroussé nose, high cheekbones and down-turned eyes and mouth. In her seventies she was still driving a Mercedes sports car, smoking 20 a day and partial to Bloody Marys and bottles of Merlot. She turned 80 while playing Mrs Higgins in My Fair Lady on Broadway, recalling: “I gave a huge party and invented my own cocktail called Diana’s Dynamite, prosecco with Cointreau, which got everyone hammered.”

In Cannes last yearJOEL SAGET/GETTY IMAGES

She freely admitted having a dark side, adding: “Doesn’t everyone?” She continued: “I’ve played a lot of evil, ball-breaking women. And, if you’re honest, you’ll just drag up from the depths all the times you’ve hated or felt passionately about something and play it.” In her free time she enjoyed escaping to her château, southeast of Bordeaux. “Well, it calls itself a château. I would call it a manor house,” she told The Sunday Times last year, adding that it only had one tower whereas “really self-respecting châteaux have two”. There she would cook for friends, read, listen to music and swim naked in her pool.

At night she listened to the owls before turning in with a “red before bed”, adding that a £3.99 bottle of Chilean merlot gives you the best night’s sleep in the world. “It’s like being hit over the head,” she told one journalist, adding that she would wake up ten hours later feeling like a spring lamb. At home in London she had a macaw called Chrome; his favourite line was: “F*** off, f*** off, f*** off.”

There was no shaking off the legacy of The Avengers, as synonymous with the Sixties as the Mini and the Beatles. “I’m on a mouse pad and a screensaver,” she mused. “Am I supposed to be flattered? All these old images of me floating across the screen, the terrible chasm of what you were and what you are. The Avengers bores me now. I was grateful because it catapulted me into stage stardom. It was good. I’m not ashamed of it. But I only did it for two years