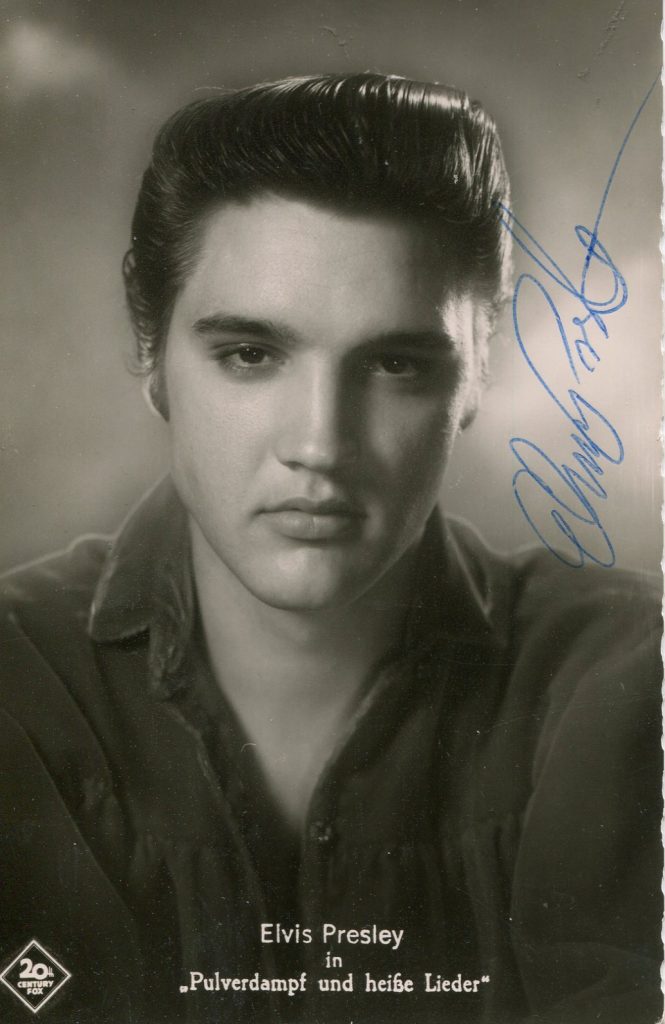

- Dubbed “The King of Rock n’ Roll,” Elvis Presley transcended multiple musical genres and entertainment mediums, ultimately becoming a global phenomenon – the 20th Century personification of America’s great potential, mirrored by its predisposition for self-destruction. As a teenager, Presley was discovered by Sam Phillips at Memphis’ famous Sun Studio, home of other future musical giants like Jerry Lee Lewis and Johnny Cash. A scant three years later, under the Svengali-like guidance of manager “Colonel” Tom Parker, the young singer exploded onto the national stage with a series of controversial TV appearances, culminating with three star-making guest spots on “The Ed Sullivan Show” (CBS, 1948-1971). The making of hit singles such as “Heartbreak Hotel” and movie roles in films like “Jailhouse Rock” (1957) were temporarily sidelined when the hip-shaking heartthrob was drafted into the U.S. Army for two years in 1958. After his triumphant return in 1960, Presley soon shifted his focus from music and live performances to his work in film. For almost 10 years, he would churn out nearly 30 films – which began a steady decline in quality by the mid-1960s – as his once prolific and groundbreaking recording career lost the relevance it had previously enjoyed. With his mesmerizing comeback in the televised special “Elvis” (NBC, 1968), Presley reinvented himself and rediscovered his passion for live performance. His historic globally broadcast live concert “Elvis: Aloha from Hawaii” (1973) would be the pinnacle of a career that had already exceeded existing perceptions of fame and success. Sadly, the years that followed saw Presley’s physical and emotional state deteriorate due to the shocking pharmacopeia he had for so long relied upon to meet the grueling demands of constant touring. When Presley died at the age of 42 in August of 1977, it was simultaneously the end of a career unlike anything the world had ever known and the beginning of a true cultural icon.

Born Elvis Aaron Presley on Jan. 8, 1935 in Tupelo, MS, Presley grew up an only child, his twin brother Jesse Garon having died at birth, a fact that was interpreted by mother Gladys as a divine omen foreshadowing her son’s destiny. When he was three, his father Vernon served an eight-month prison term for writing bad checks, and thereafter, the senior Presley’s erratic employment kept the family just above the poverty level. The Pentecostal services attended by the Presleys first exposed the young Elvis to music, and his fifth place finish at the Mississippi-Alabama Fair and Dairy Show for a rendition of Red Foley’s “Old Shep” was the first indication that singing would play a major role in his life. The family’s move to Memphis, TN in 1948 soon placed him in the ideal environment to forge his distinctive style. Hanging around the city’s historic Beale Street, Presley absorbed the blues and gospel music he heard at the all-night clubs and eventually bought clothes that reflected the milieu. Further influenced by his new surroundings, Presley grew out his hair in a slicked-back pompadour, presaging the rebel image he would be known for years later. While at Memphis’ L.C. Humes High School, he entered a student talent show and was buoyed by the enthusiastic response his performance generated. After graduating from high school, Presley worked for a period at a local machine shop. Later that summer he stopped by Sun Studio to record a demo of two songs, which he planned to give to his mother as a belated-birthday gift. Although Sun owner Sam Phillips was not present at this first recording, the two would meet several months later when Presley returned. Although unsure of what to do with his untrained performance style, Phillips was intrigued by what he saw and heard in the young man.

In the summer of 1954, Phillips teamed the young Presley with local musicians Scotty Moore on guitar, and Bill Black on bass, for a series of recording sessions. Although he was initially unimpressed by the results, Phillips took notice when the trio spontaneously launched into an improvisational, sped-up version of Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup’s “That’s All Right.” The song, accompanied by a rendition of “Blue Moon of Kentucky” would become the first of five singles for the Sun label. Throughout the remainder of the summer, Presley, Moore and Black toured locally throughout the South and their singles enjoyed moderate success. That fall, after a disappointing performance at the venerated Grand Ole Opry, Presley and his band mates began appearing on “The Louisiana Hayride” radio broadcasts out of Shreveport’s KWKH. It was during his association with Hayride that Elvis met “Colonel” Tom Parker, a promoter and manager for country music star Hank Snow. Gradually, over the course of that year’s touring schedule, Parker would become more and more involved with Elvis’ career. By the summer of 1955, the crafty Colonel had signed a deal that made him Presley’s sole manager – a position that, for better or worse, he would maintain until the star’s death. As Presley’s popularity grew, so too did the interest of major record labels in signing him. In October of that year, Parker brokered a deal that sold the singer’s Sun recording contract – and the rights to the previously recorded material at Sun – to RCA Victor for an unprecedented $40,000. Of the young artists at the forefront of the new “rockabilly” wave of music, Presley was by far the most charismatic and popular.

In January of 1956, Presley recorded his first album with RCA. Among the tracks laid down during the session was the future signature hit single “Heartbreak Hotel” – which would soon become the performer’s first gold record. Presley made his national TV debut on the Dorsey Brothers’ “Stage Show” (CBS) on Jan. 28, 1956, followed soon by six consecutive appearances on the series. With his self-titled debut album climbing the charts, Presley undertook a two-week engagement at the New Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas – an early engagement that was not well-received by the older, conservative crowd – prior to two appearances on “The Milton Berle Show” (NBC, 1948-1956) that summer. It was his second performance on the show, during which Presley launched into a wild pelvic gyration while performing his hit song “Hound Dog,” that sparked nationwide controversy and charges of lewdness by several entertainment critics. After that great arbiter of American good taste, Ed Sullivan, vowed never to have “Elvis the Pelvis” on his show, Presley took his act to Sullivan’s competition, “The Steve Allen Show” (NBC, 1956-1960). Although the singer did not appreciate being asked to sing his new hit song alongside an actual basset hound – dressed in a tuxedo, no less – Presley good-naturedly went along, and the performance drew huge ratings. By now Sullivan realized he had been scooped by Berle and Allen. In an about-face, he invited Presley to appear on “The Ed Sullivan Show” (CBS, 1948-1971) for three appearances, for which the singer received an astonishing $50,000. His first appearance on the variety show broke ratings records. When Presley returned to Tupelo to perform again at the Mississippi-Alabama Fair and Dairy Show, National Guardsmen were called in to assist with crowd control. In the fall of that year, Presley’s first film “Love Me Tender” (1956) premiered, with both the movie and corresponding soundtrack becoming certifiable hits. In January 1957, he made his third and final appearance on the Sullivan show, during which he was famously filmed only from the waist up. After the performance, Sullivan gave Presley his official seal of approval when he announced on air that Elvis was “a decent, fine boy.”

Elvis mania was in full bloom, not only across America, but as far abroad as the Soviet Union, where rumors began to circulate that Presley’s records were being sold on the black market. His first three singles released in early 1957 all went to No. 1, as he completed filming his second feature film “Loving You” (1957), and continued to perform live for throngs of increasingly hysterical teenage girls. In the spring of that year, Presley purchased Graceland manor in Memphis, in which he and his parents would reside. His third film, “Jailhouse Rock” (1957) – featuring the iconic cellblock title song performance that would be the precursor for MTV music videos some 30 years later – went on to become an even bigger box-office success than “Loving You,” with the EP for the title song also reaching No. 1 on the charts. Rioting at Presley’s concerts was now commonplace, drawing the derision of such established musical luminaries as Frank Sinatra over rock-and-roll in general. Near the end of the year, he received his official draft notice from the U.S. Army; something he and his family knew had been inevitable for some time. Given a deferment before being inducted, Presley filmed and recorded the soundtrack for his fourth film, “Kid Creole” (1958), a movie that would become largely regarded as the singer’s most accomplished and promising cinematic performance. In March 1958, he began basic training at Fort Hood, TX, after a much publicized induction process during which he was photographed getting his famous pompadour buzzed. Despite his fears that his time away from the entertainment industry would damage his career, Presley committed to fulfill his duty as a regular enlisted soldier, and without preferential treatment.

In August of that year, while still in basic training, Presley was dealt a devastating blow when his beloved mother, Gladys, died after a bout of acute hepatitis. In the fall he and his company set sail to Germany aboard an Army transport ship, where he was stationed for the next 18 months. During this time Presley was introduced to karate and amphetamines, both of which remained constants throughout the remainder of his life. He was also introduced to 14-year-old Priscilla Beaulieu, the step-daughter of an Air Force Captain stationed nearby. Having planned ahead, Parker had arranged for Presley to record a number of songs before leaving for the Army, and during his stint abroad, he still managed to have a total of 10 hits in the Top Ten. In March of 1960, Sergeant Elvis Aaron Presley was formally discharged from the Army, and returned stateside to be greeted by hordes of jubilant fans. Immediately, he set about recording the homecoming album appropriately titled Elvis is Back!, which went on to spawn several hit singles, including the operatic “It’s Now or Never” and the ballad “Are You Lonesome Tonight?” In May, Elvis appeared on “The Frank Sinatra Timex Special” (ABC, 1960). Known more popularly as the “Welcome Home, Elvis!” special, it was ironic, considering Sinatra’s unflattering assessment of Presley and his music in the press barely two years prior. In the fall, his fifth film, “G.I. Blues” (1960), was released and performed exceptionally well at the box-office.

From early in his career, Presley had envisioned a serious pursuit of acting in films and by 1961 Parker had set in motion an assembly line of formulaic productions for Elvis to star in. Initially, the performer had pushed for more dramatic roles, with less emphasis on musical numbers. However, when the two follow-up efforts – the Don Siegel directed “Flaming Star” (1960) and “Wild in the Country” (1961), written by famed playwright Clifford Odets – failed to live up to expectations, Presley reluctantly agreed to revert to the tried-and-true recipe of exotic locales, musical interludes, and loads of pretty girls. Critically panned, the films were nonetheless profitable, and for the remainder of the decade he would churn out nearly 30 more pictures. In the early half of the 1960s, many of the films produced hit soundtrack albums, including the LP for “Blue Hawaii” (1961), which yielded the No. 2 single “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” a song destined to become a Presley classic. During his Hollywood sojourn, Presley enjoyed only one non-soundtrack No. 1, “Good Luck Charm” in 1962. One of the few bright spots of the movie cycle was “Viva Las Vegas” (1964), which despite the usual lackluster plot, paired Elvis with Ann-Margret – possibly the only film in which Presley’s co-star exuded nearly as much charisma and sexual energy as the King himself. Such was their onscreen chemistry that rumors of an affair soon circulated, as did similar stories of Colonel Parker being unhappy with the talented starlet potentially upstaging his client. As Parker and Presley ground out movie after movie in this fashion, the singer’s musical reputation was undeniably damaged, while acts like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan, supplanted Elvis’ place in the pop-culture zeitgeist.

After more than seven years of a relationship largely kept under wraps due to her young age, Presley married the now legal Priscilla Beaulieu a small ceremony at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas in May of 1967. Barely nine months later, Priscilla gave birth to their first and only child, Lisa Marie Presley. When the soundtrack for Presley’s latest movie effort “Clambake” (1967) failed to climb past the 40th position on the charts, Parker set his sights on television as a means to resurrect his client’s suffering musical reputation. Originally envisioned as a gimmicky Christmas special, “Elvis” (NBC, 1968) would serve as the resurrection of the rock-n-roll icon and consummate performer, and would later be popularly referred to as “The ’68 Comeback Special.” Clad entirely in black leather with his guitar slung across his shoulder, Presley enthralled with an energetic, yet informal jam session, surrounded by his longtime band mates. It was as if the 33-year-old musician were unleashing nearly a decade’s worth of pent up artistic energy in a performance that floored audiences and critics alike. By the time Presley, in an elegant two-piece white suit, performed the inspirational ballad “If I Can Dream,” he was a man reborn, both in the eyes of his fans and his own. The program went on to become NBC’s highest rated of the year, and put to rest any fears that Presley’s artistic prowess had lessened during Tinseltown exile. He immediately entered the American Sound Studio in Memphis and began recording. These sessions would produce such late-career hits as “In the Ghetto,” “Suspicious Minds,” and “Kentucky Rain.”

Hungry to return to concert performances – something he had not done in years – Presley began a series of 57 performances at Las Vegas’ new International Hotel in the summer of 1969. Whereas his earlier stint in Sin City had proved one of the most embarrassing of his career, his return was a triumph, breaking previous Las Vegas attendance records and spawning his first live album, Elvis in Person at the International Hotel. It was around this time that he began wearing his signature high-collared, karate uniform-inspired outfits, the precursors to the sequined, one-piece jumpsuits he would later be known for. That same year, “Change of Habit” (1969), co-starring Mary Tyler Moore, was released, marking his final appearance as an actor in a film. Presley’s renewed popularity continued to grow through his concert appearances, recordings, and two documentaries, “Elvis: That’s the Way It Is” (1970) and “Elvis on Tour” (1972). Unfortunately, Presley’s constant touring – and rumored infidelities – took its toll on his marriage with Priscilla, and by August of 1972 the couple had filed for divorce. In January of the following year, Presley made television history with “Elvis: Aloha from Hawaii” (1973). A massive benefit concert for the Kui Lee Cancer Fund, it became the first program to be broadcast live via satellite around the world. When the show was aired again on NBC in April of that same year, it broke records by garnering a full 57 percent share of the American viewing audience. Although Elvis appeared to be at the top of his game, all was not well behind the scenes. After more than a decade of escalating pharmaceutical drug abuse, he was deteriorating physically as well as emotionally.

At the very pinnacle of superstardom, Presley threw himself into a hectic schedule of touring, punctuated by sporadic recording sessions in Memphis. By October 1973, Priscilla’s divorce from Elvis was granted. She would later claim that once the couple consummated their relationship on their wedding night, Presley lost interest in her sexually. Regardless of their unorthodox, slightly suspect relationship, they couple remained in love with one another even post-divorce. Presley finished the year having performed in upwards of 168 live shows, and made plans to increase the number in 1974. In order to maintain the unforgiving regimen, the rock icon relied more and more on an astounding array of pharmaceuticals supplied to him by a cadre of doctors, some of whom tried, however ineffectually, to moderate his intake more than others. Twice in the previous year Presley had overdosed on barbiturates, lapsing into a coma in his hotel room for three days on the first occasion, and being admitted to a hospital in a semi-comatose condition on the second. Longtime friends – those who dared to speak out – begged him to take a break from touring and focus on his health, to no avail. The next few years saw Presley’s weight balloon alarmingly as his concerts became marred by slurred lyrics, abbreviated performances, or outright cancellations. He became increasingly paranoid and spent days at a time holed up in his hotel room or in his bedroom at Graceland. Presley’s distrust of those closest to him was only exacerbated after the release of the tell-all book Elvis: What Happened?. Co-written by three of his ex-bodyguards, it was the first public disclosure of Presley’s abuse of prescription drugs and erratic behavior. However, despite his infrequent recording sessions and the concerns of RCA, Presley nonetheless managed to release several albums during this period, including Promised Land and Moody Blue.

In November of 1976, Presley, who had been touring almost non-stop for nearly two years, broke up with girlfriend Linda Thompson, a woman he had been with since his separation from Priscilla. Within weeks, he began dating Ginger Alden, a former beauty queen, half his age. In the spring of 1977, Presley, whose health was in a precipitous decline, was hospitalized and the remainder of a planned tour was canceled. When he returned to the stage that summer, Presley’s final live performances were captured on film for a planned TV special “Elvis in Concert” (CBS, 1977). The footage revealed a shocking image of the once vibrant, quintessential showman reduced to a bloated, sweaty caricature of his former self. After a nearly two-month break, Presley prepared to go back on the road, beginning with a first appearance in Portland, ME. After spending time with family and friends on the morning of August 16, he retired to his master suite at Graceland. Hours later, Alden discovered an unconscious Presley collapsed on his bathroom floor. Attempts to revive him failed, and he was pronounced dead later that afternoon, setting off a tidal wave of disbelief and anguish from Elvis fans across the world. Two days later, Presley’s funeral was held at Graceland, attracting massive media attention, and a processional of devotees numbering approximately 80,000 people. Elvis Aaron Presley was just 42 years old.

The King, however, would never truly die in the hearts of fans. Almost immediately after his death, so-called sightings of a very much alive Elvis proliferated across the globe and Presley impersonating grew into a cottage industry for devoted fans and frustrated crooners everywhere. His only child, Lisa Marie, grew up under the watchful, often intrusive, eye of the tabloid press who reported her every move. Scores of books detailing every aspect of his life have been written, accompanied by a myriad of documentaries and biopics, including “Elvis” (ABC, 1979), directed by John Carpenter and starring Kurt Russell in a convincing portrayal of Presley. Even relatively minor events in Presley’s life were meticulously recreated in works such as “Elvis Meets Nixon” (Showtime, 1997), which chronicled the real-life weekend encounter between the performer and scandal-plagued former president. More pervasive was Presley’s music, which continued to sell records decades after his passing, and was used in hundreds of film and television projects over the years. Notably, the George Clooney/Brad Pitt heist movie “Ocean’s Eleven” (2001) made wonderful use of a remixed version of Presley’s “A Little Less Conversation” – a song that had not even been a hit during the singer’s lifetime. Even the horror comedy “Bubba Ho-Tep” (2002), starring Bruce Campbell as a decrepit Elvis who, along with an elderly black man claiming to be JFK (Ozzie Davis), battles a soul-devouring mummy was a bizarre homage to the King of Rock-n-Roll. Nearly 40 years after his death, the continued public fascination with Elvis Presley remained as strong as ever.

This TCM overview can also be accessed online here