Obituary from “The Guardian” 2011.

Anna Massey, who has died of cancer aged 73, made her name on the stage as a teenager in French-window froth. She then graduated, with effortless and extraordinary ease, to the classics and to the work of Samuel Beckett, Harold Pinter and David Hare. In later years, she became best known for her award-winning work in television and film. What constantly impressed was her fastidious intelligence and capacity for stillness: always the mark of a first-rate actor.

Born in Thakeham, West Sussex, she was bred into show business although, in personal terms, that proved something of a mixed blessing. Her father was Raymond Massey, a Canadian actor who achieved success in Hollywood; her mother was Adrianne Allen who had appeared in the original production of Noël Coward’s Private Lives. Anna’s godfather was the film director John Ford.

Since her father fled the family home when she was a child and her mother prided herself on being a lavish hostess, the young Anna relied heavily on the family nanny for emotional comfort. There was an air of resonant solitude about many of her best performances that may have stemmed from her childhood.

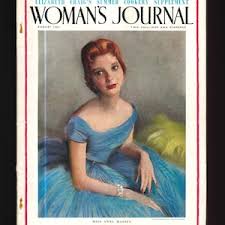

She had a privileged upbringing and a peripatetic education in Europe and the US. Although never formally trained as an actor, she made a strikingly confident debut at the age of 17 in a William Douglas-Home trifle, The Reluctant Debutante. Playing the obstinate, sweetly peevish daughter of troubled, upper-class parents (Celia Johnson and Wilfrid Hyde-White), she captured many of the notices and was praised by the critic Ivor Brown for displaying “a nice, down-to-earth determination”. The play had a long run at the Cambridge theatre in 1955 before moving to New

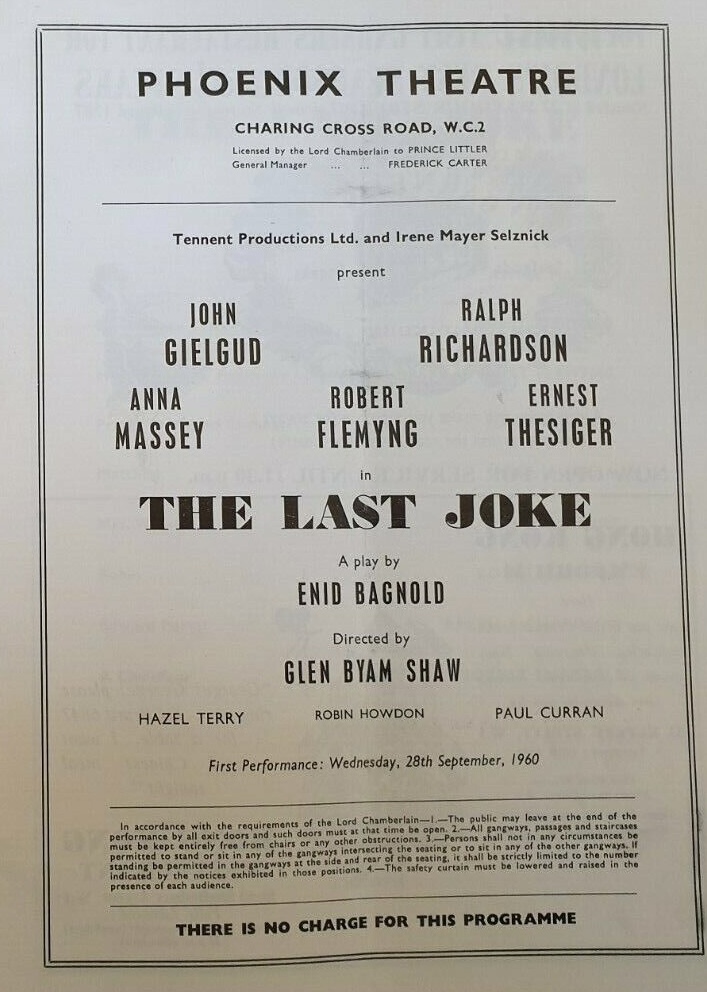

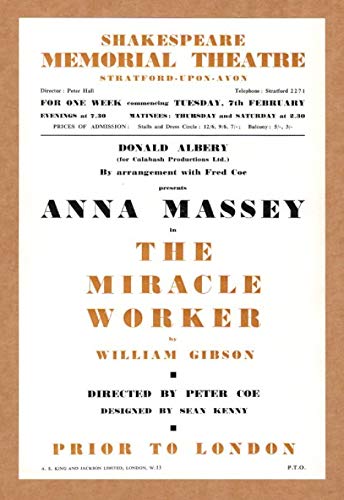

For a while it looked as if Massey would be trapped in a series of evanescent comedies. Returning to London from New York, she went straight into another lightweight piece, Dear Delinquent. But proof that Massey had set her sights somewhat higher came in 1958 when she appeared in TS Eliot’s classically influenced verse drama The Elder Statesman, prompting Kenneth Tynan to remark that “Anna Massey, of the beseeching face and shining eyes, is a first-rate stand-in for Antigone”. She demonstrated that she could carry a show when, in 1961, she played Annie Sullivan, the persistent and faintly sadistic teacher of an undisciplined, disabled girl in William Gibson’s The Miracle Worker.

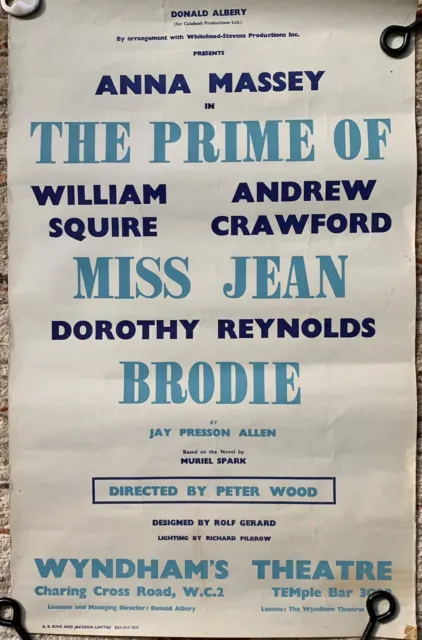

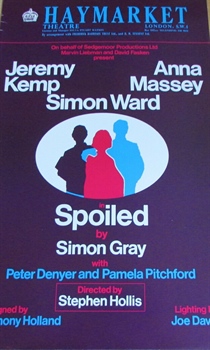

After that the lead roles came pouring in. She was Lady Teazle in John Gielgud’s elegant, starry Haymarket revival of The School for Scandal in 1962, in which her brother, Daniel, also appeared. She returned to the same theatre in 1963 to play Jennifer Dubedat in George Bernard Shaw’s The Doctor’s Dilemma and again in 1965 to play the fragile Laura Wingfield in Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie. In 1966, she took over from Vanessa Redgrave as Muriel Spark’s mind-bending dominie in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie at Wyndham’s theatre.

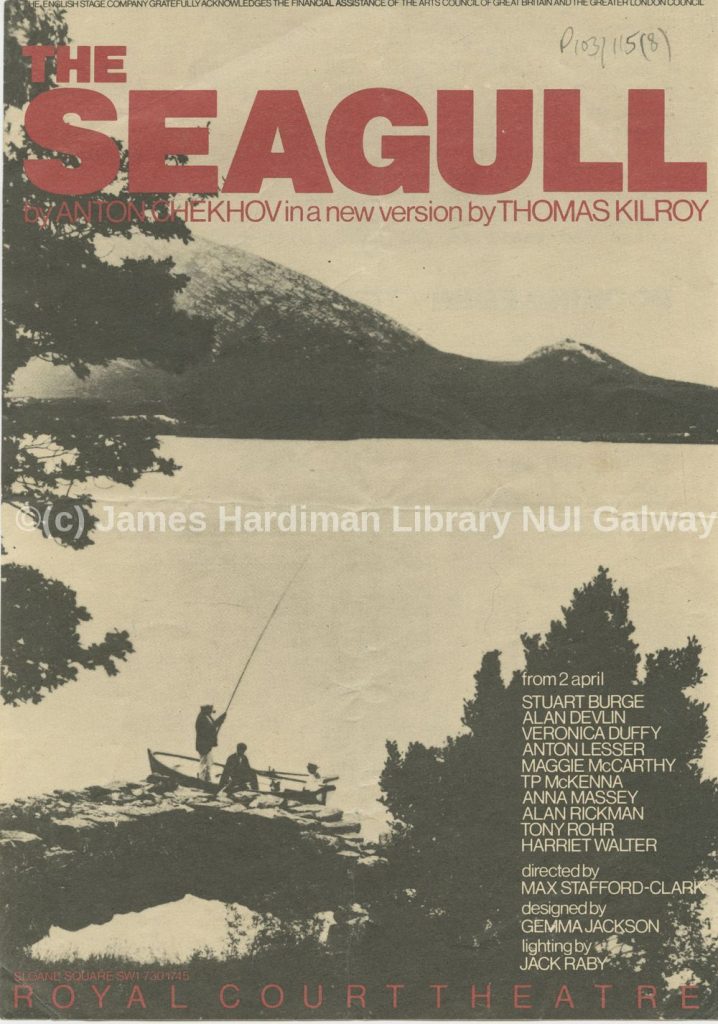

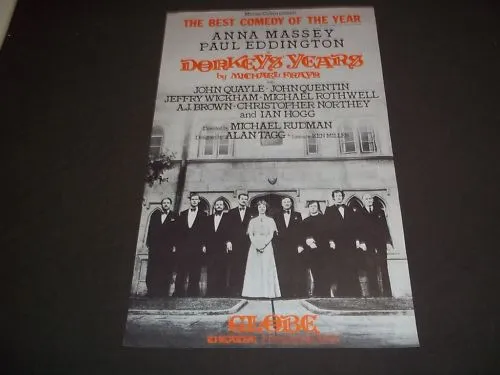

Combining delicate beauty with a hint of inner steel, she could have continued as an archetypal West End leading lady. But a major shift in her career occurred in 1971 when she went to the Royal Court to appear in David Hare’s Slag, which showed three female teachers resolving to abstain from sex: as the eldest of the three, full of old school ties and sporting inclinations, she was unnervingly funny. She was equally good as the arrogantly colonialist Lady Utterword in Shaw’s Heartbreak House at the Old Vic in 1975, and even appeared, heroically, as one of three figures encased in urns in Beckett’s Play at the Royal Court in 1976.

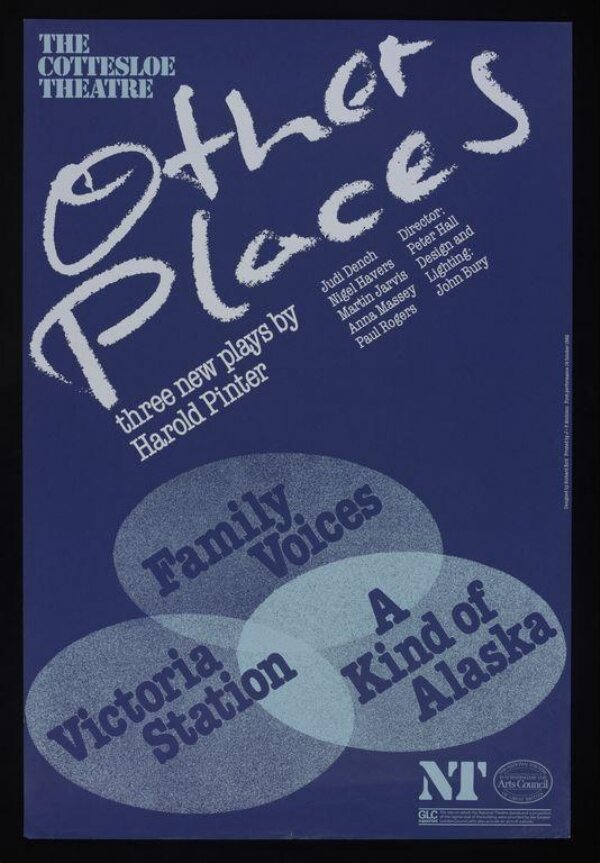

She had come a long way from the boulevard divertissements of her youth. And if, in later years, her stage appearances became regrettably fewer, they were all memorable. I have never forgotten how, in Pinter’s A Kind of Alaska at the National in 1982, she and Paul Rogers reacted to the reawakening of Judi Dench’s victim of sleeping sickness with an amazed, compassionate stillness.

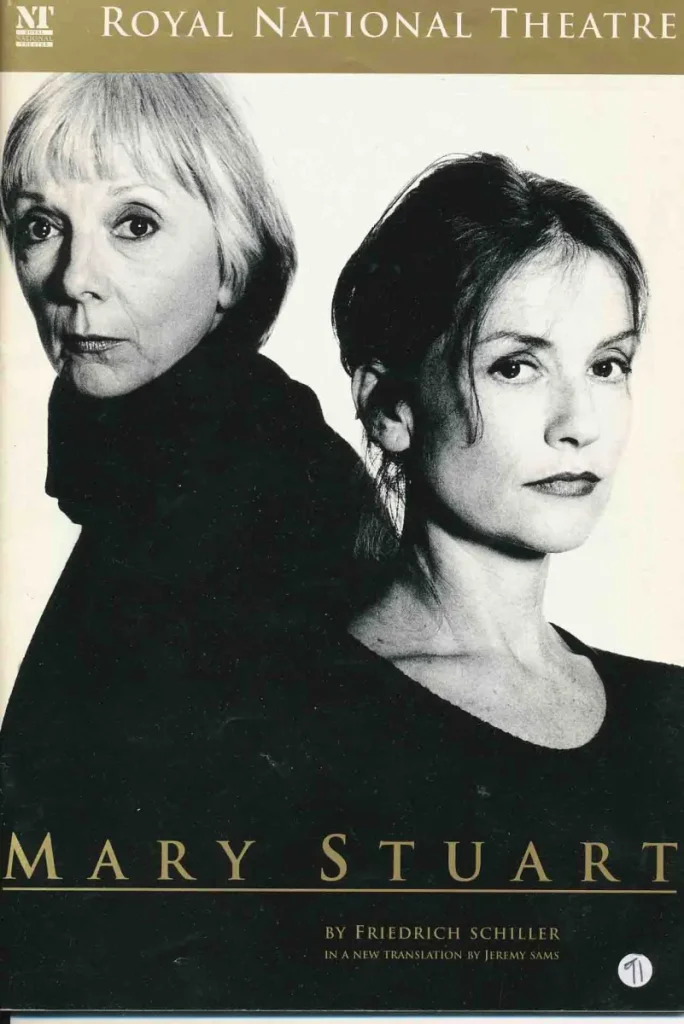

No less treasurable was her performance as Bel in Pinter’s Moonlight at the Almeida in 1993. Patiently tolerant with her raging husband, she registered pure hollow-eyed despair when her estranged sons rejected her pleading telephone call. When she played Elizabeth I to Isabelle Huppert’s Mary Stuart in Friedrich Schiller’s historical drama at the National in 1996, she was flawless in her aching sense of regal solitude.

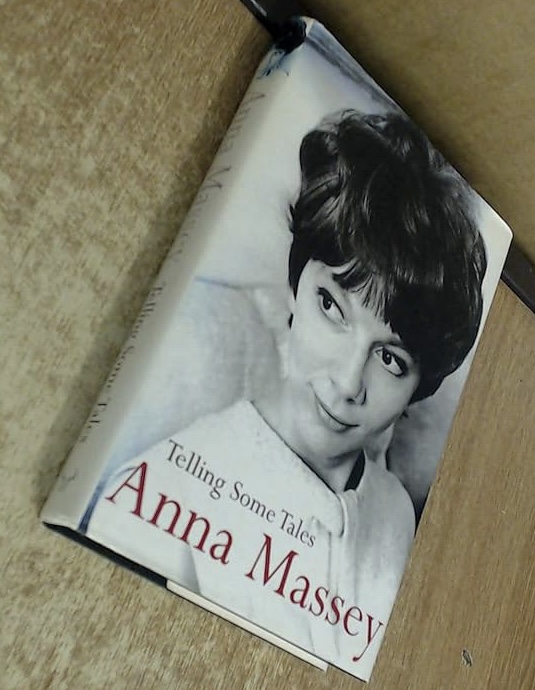

She was appointed CBE for services to drama in 2005 and, in the following year, published an autobiography, Telling Some Tales. Massey was a consummate actor and, in my one brief encounter with her, sitting next to her at a Canadian ambassadorial dinner, a delightful woman. I remember we spent much of the evening discussing her passion for televised snooker. That seemed to symbolise the fact that, in her career as well as her life, she was always capable of the unexpected.

She married the actor Jeremy Brett in 1958. The marriage was dissolved in 1963. In 1988 she married Uri Andres, a Russian metallurgist at London’s Imperial College. She is survived by Uri; her son, David, from her first marriage; and two grandchildren.

Ronald Bergan writes: Michael Powell’s lurid Peeping Tom (1960) provided Anna Massey with her second, and most significant, film role in a 50-year career on screen. Massey gave a wonderfully sympathetic performance as the naive downstairs neighbour of a psychotic landlord (Karlheinz Böhm) whom she finds both repellent and attractive. More often, Massey, with her cut-glass English accent, conveyed a cold and repressed character on screen.

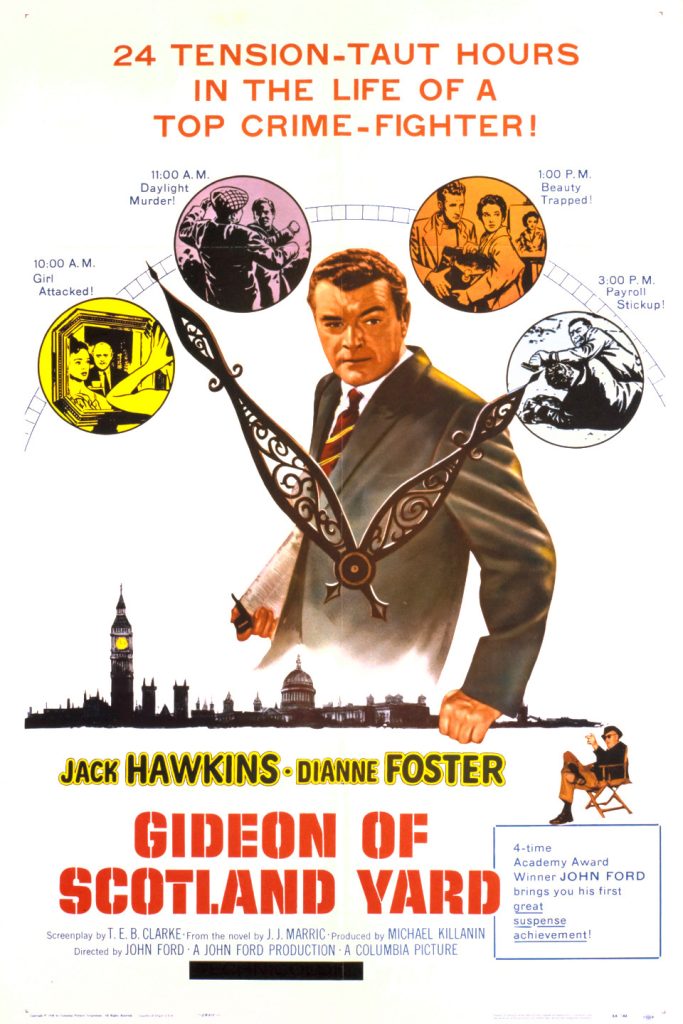

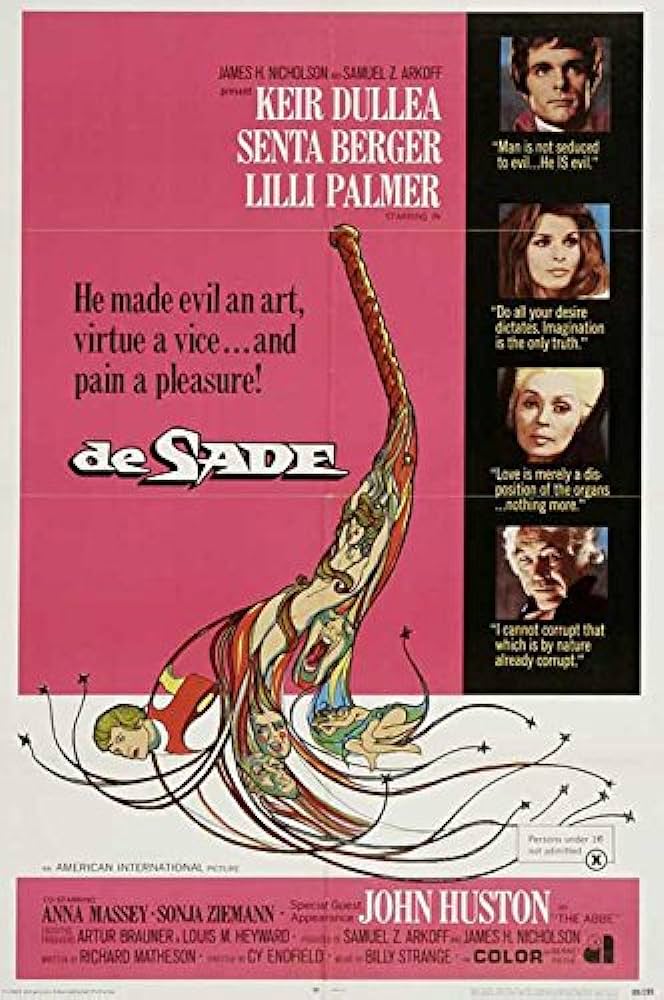

She had made her feature film debut aged 21 in Ford’s uncharacteristic Gideon’s Day (1958) as the daughter of a Scotland Yard inspector played by Jack Hawkins. In Otto Preminger’s Bunny Lake Is Missing (1965), she was a nervous teacher. In 1969, she seemed content to play Anthony Hopkins’s frustrated wife in The Looking Glass War and, in De Sade, a plain-looking woman married to the naughty marquis (Keir Dullea), while he romps around with her sexy sister.

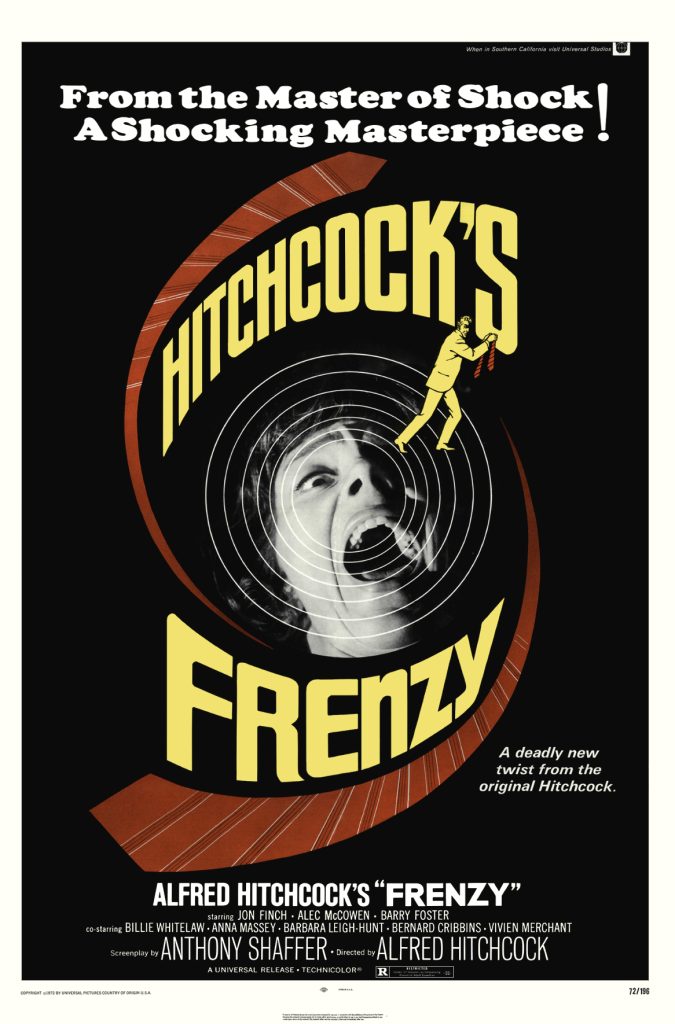

In Alfred Hitchcock’s Frenzy (1972), she was strangled by the “Neck-Tie Murderer”, bundled into a sack full of potatoes and thrown on to a moving truck. Somehow it was as if Hitch wanted to make amends for her being spared from death in Peeping Tom.

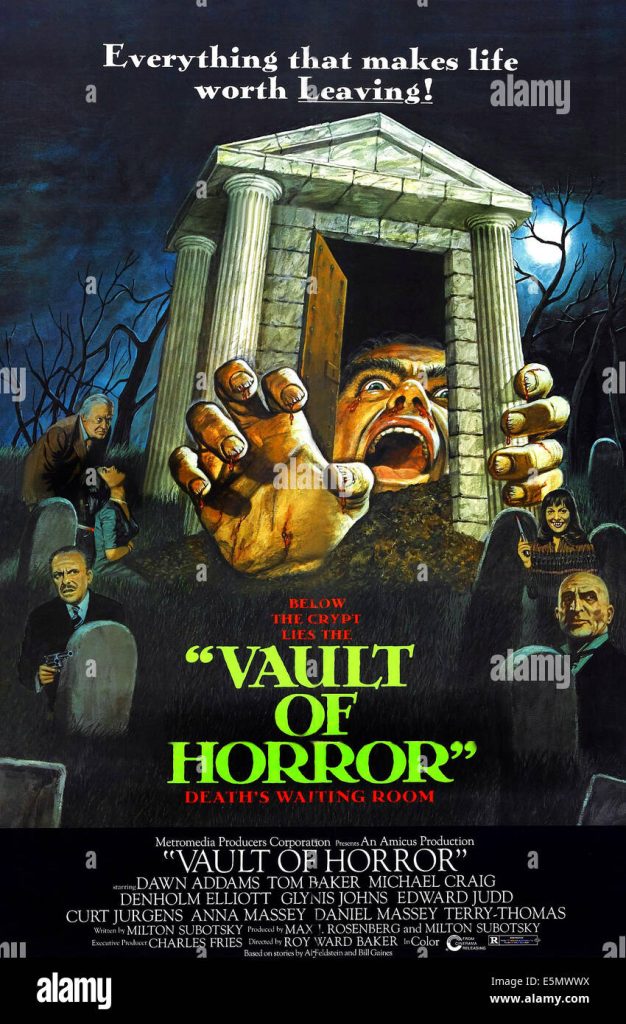

The following year, in an episode entitled Midnight Mess from the portmanteau film Vault of Horror (1973), she was murdered by her brother (played by her real-life sibling Daniel) for her inheritance, although she turns out to be a vampire who serves her murderer tomato juice in a restaurant which happens to be his blood. By way of contrast, she also appeared that year, with Hopkins and Claire Bloom, in A Doll’s House, adapted from Henrik Ibsen’s play.

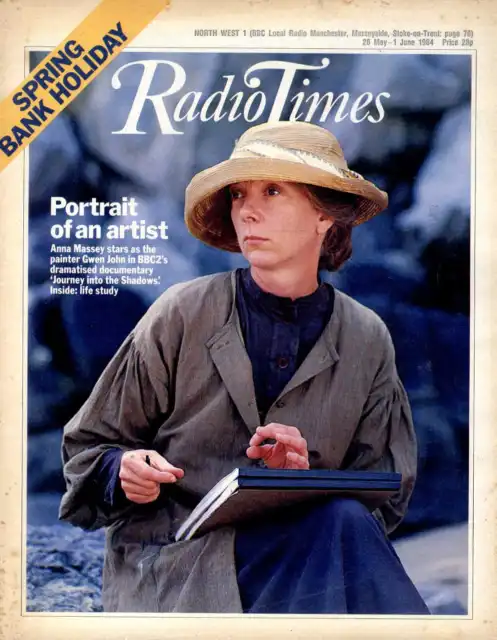

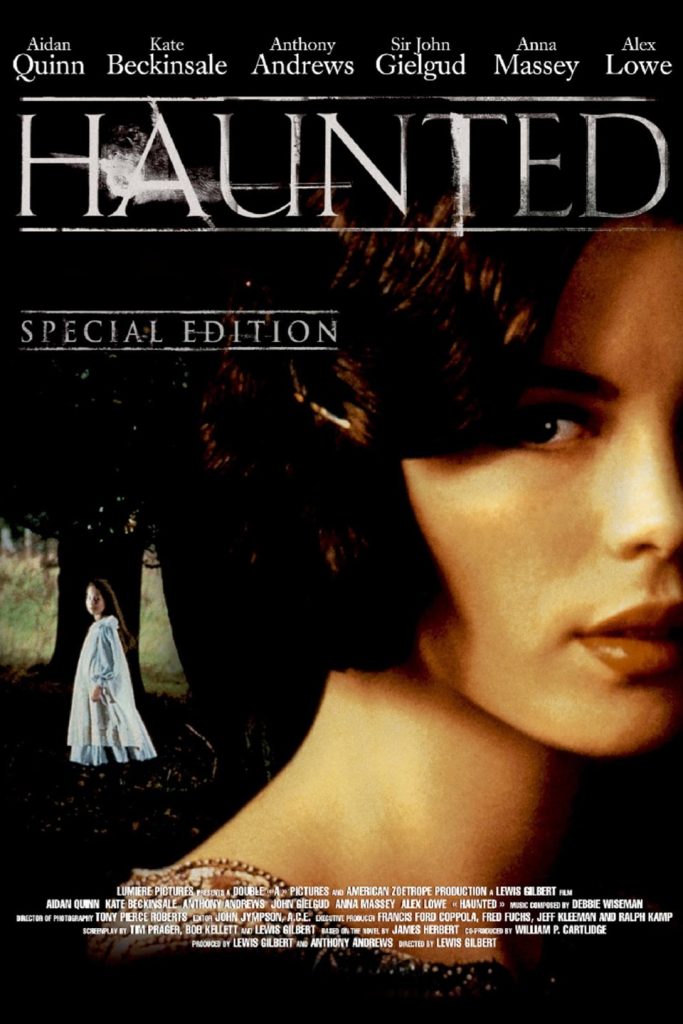

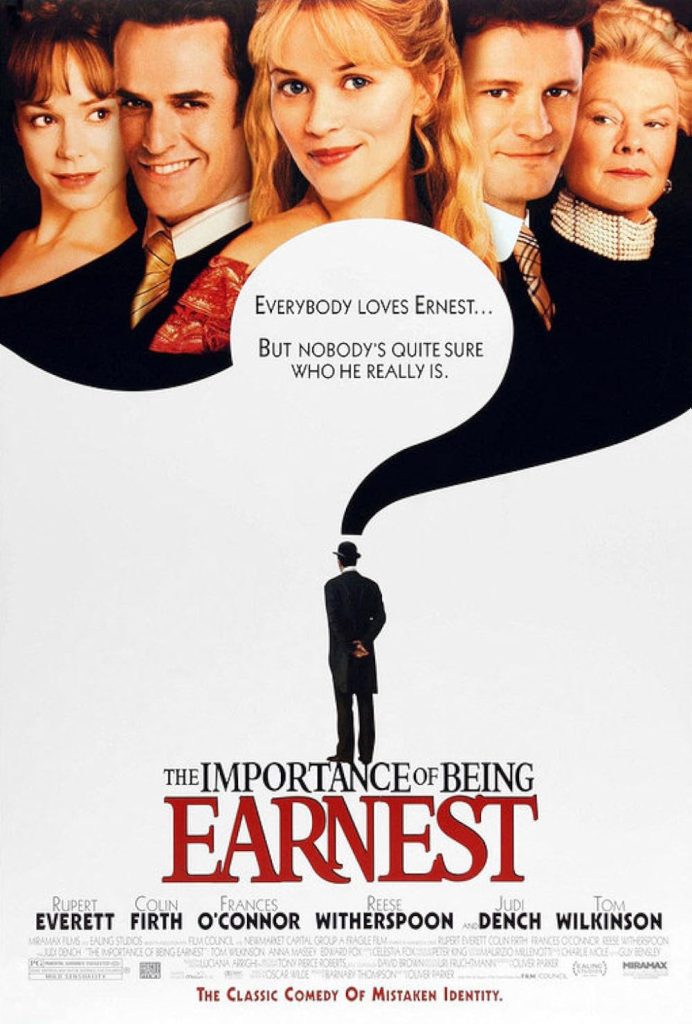

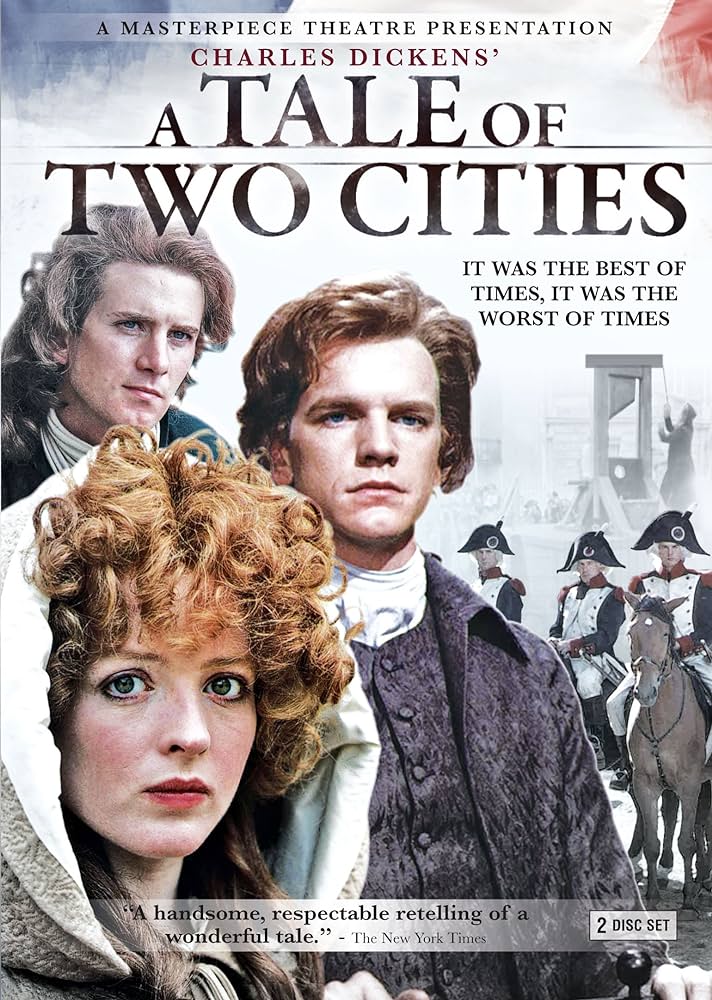

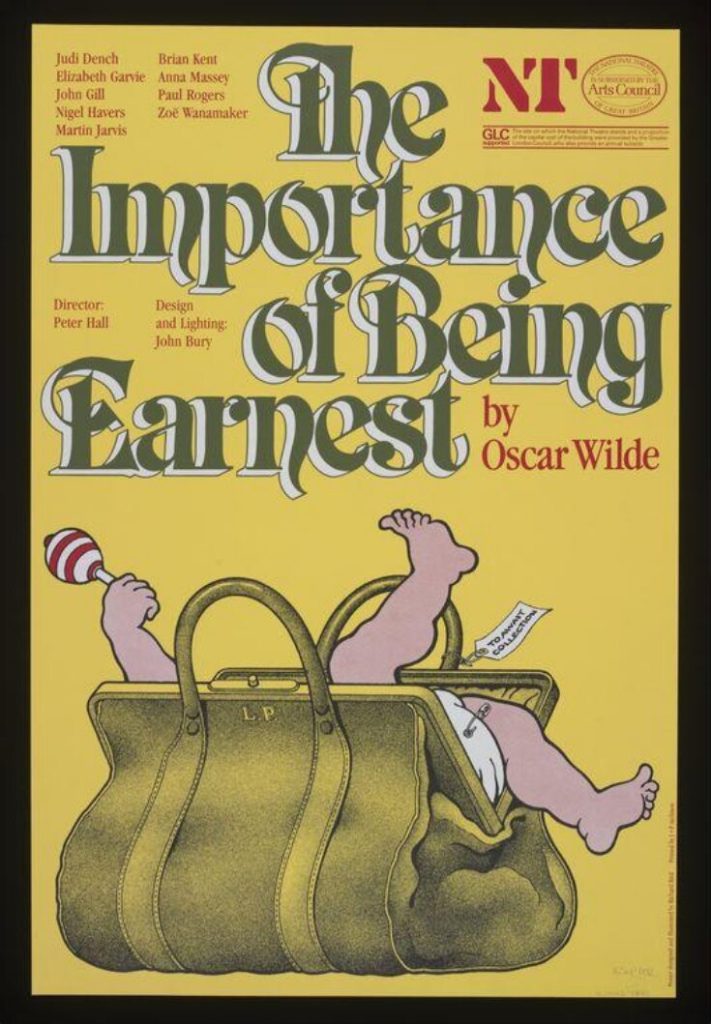

Variously cast in roles such as nannies, nuns and nurses, Massey starred in dozens of British and American films, including The Importance of Being Earnest (as Miss Prism, 2002) and Possession (2002) and, in particular, television productions, which were far more rewarding. The most prominent of these were literary adaptations which offered roles such as Titania in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1964), Lucetta in The Mayor of Casterbridge (1978), a creepy Mrs Danvers in Rebecca (1979), Aunt Norris in Mansfield Park (1983) and Miss Pross in A Tale of Two Cities (1989). Massey also had parts in the TV series The Pallisers (1974), Couples (1976), The Diamond Brothers (1991) and Midsomer Murders (1998, 2009) and as Lady Thatcher, opposite Derek Jacobi, in Pinochet in Suburbia (2006).

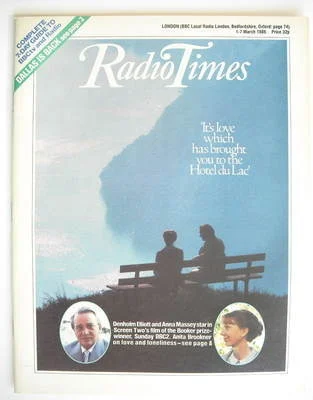

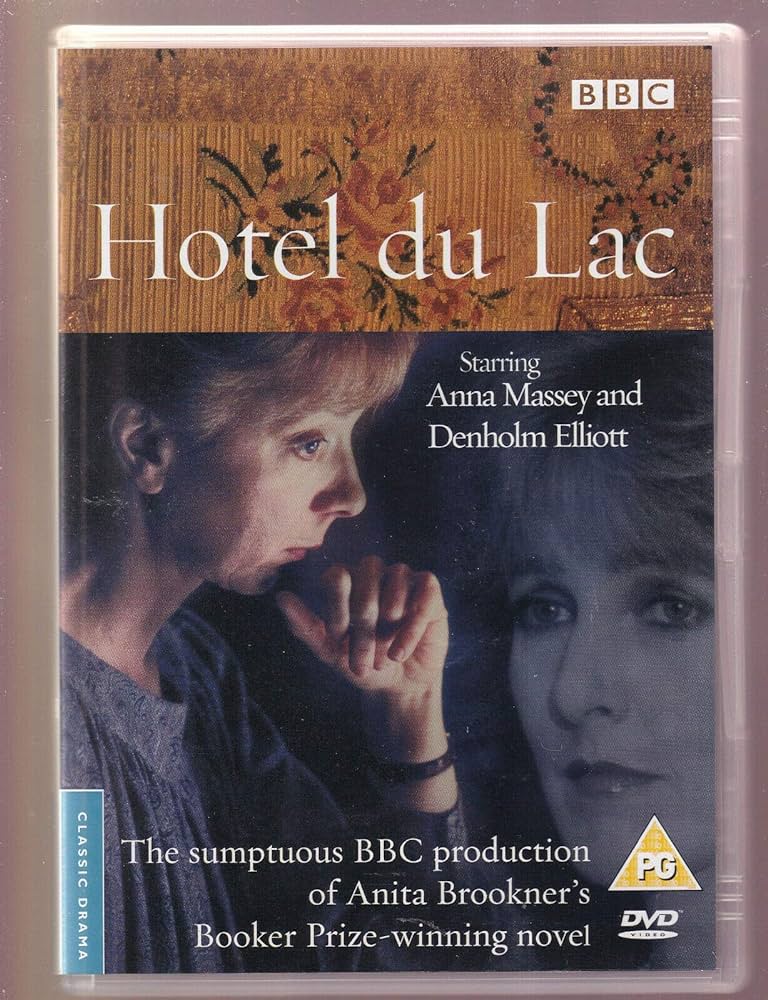

Perhaps her greatest triumph on television was her Bafta-winning performance as the lonely writer of romantic fiction on holiday in Switzerland in Hotel du Lac (1986), Christopher Hampton’s adaptation of Anita Brookner’s novel. It was the sort of role in which Massey was supreme: placid on the surface, with passion deep within her