Tcm overview

“‘I guess I’m not a real movie star, in the sense of being a personality’ said Al Pacino once. ‘People hardly ever recognize me in public – or at other times’ he admitted ruefully, they mistook him for Dustin Hoffman. He is less puckish, more soulful than Hoffman but consequently we tend to lose him – which has been a distinct advantage in the best films that he has made, ‘Serpico’ and ‘Dog Day Afternoon’. Both were based on actual events and both were directed by Sidney Lumet on New York locations. Both took what seemed to be a documentary approach to their subjects, so that the people rather like us – not movie people, but the people you ride with on the subway. It helped too that Pacino did not seem to be acting but one left the cinema with the impression of a first-rate talent. – David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars – The Independent Years”. (1991).

Al Pacino first established himself on the cinema screen in a major way in his role of Michael Corleone in “The Godfather” in 1971. He is one of the most interesting actor in U.S. cinema and even now as he approaches his seventies he is a force to be reckoned with. His most intriguing role as far as I am concerned is “Sea of Love”.

TCM overview:

Arguably the greatest and most accomplished actor of his generation, Al Pacino became a cultural icon thanks to revered performances in a wide range of classic films, including “The Godfather” (1972), “Scarface” (1983) and “Glengarry Glen Ross” (1992). Coming to prominence during the 1970s – a period commonly regarded as Hollywood’s last Golden Age – he possessed none of the classic features of leading men from Tinseltown’s previous heyday, but nonetheless, enthralled audiences with absorbing performances on screens both large and small. As a Method actor, Pacino revealed the dark complexities of characters like Frank Serpico, Sonny Wortzik and Colonel Frank Slade. But in life, the actor remained an elusive figure, preferring to avoid disclosing anything of a personal nature. Despite such reluctance to open up about his life, Pacino maintained a long, prominent career in which he accomplished acting’s rarest of feats – winning Oscar, Emmy and Tony awards.

Born on April 25, 1940 in South Bronx, NY, he was raised by his mother, Rose, and maternal grandparents, after his father, Salvatore, an insurance salesman and restaurateur, abandoned the family when Pacino was two years old. Thanks to being exposed to theater and movies through his mother, he alleviated loneliness and shyness by acting out scenes from “The Lost Weekend” to wh ver would pay attention. Pacino later attended The School of Performing Arts, but dropped out when he was 17; instead studying at HB Studio and apprenticing at such avant-garde off-off-Broadway venues as Elaine Stewart’s Cafe LaMaMa and Julian Beck and Judith Malina’s Living Theatre. In one of those life changing events that seemed innocuous at the time, Pacino was cast in August Strindberg’s “Creditors,” directed by Charlie Laughton – the two went on to be lifelong friends – an experience that convinced him that he could be an actor. Pacino moved on to train at the fabled Actors Studio under Lee Strasberg, acquiring the Method acting intensity that propelled him to stardom.

Pacino first made his mark with an OBIE-winning performance as Murph, one of two men terrorizing an Indian (John Cazale) in Israel Horovitz’s “The Indian Wants the Bronx” (1968). The following year, he won his first Tony Award playing Bickham, a drug-addled psychotic in Don Petersen’s “D s the Tiger Wear a Necktie?” After making his feature debut in “Me, Natalie” (1969), Pacino landed his first leading role – as another drug addict – in “Panic in Needle Park” (1971). His bravura performance in that quirky film grabbed the attention of director Francis Ford Coppola, who persuaded a skeptical Paramount Studios to accept the actor as the dark and brooding mob boss Michael Corleone in “The Godfather.” Though Marlon Brando and Robert De Niro won Oscars for portraying Vito Corleone in the compelling original and even better sequel, “The Godfather, Part II” (1974), it was Pacino’s Michael that dominated both films, maturing from a cherubic war hero to cold-blooded mobster, who coolly orders executions, including one on his own brother (Cazale). Pacino was the right actor at the right time to play the lonely tyrant – his finely calibrated, dark volatility perfectly embodying the alienation and moral tumult of the decade.

Trading on the moody romanticism of his sad, sunken eyes, Pacino become a major star of the 70s, enjoying a four-year career roll practically unmatched in film history. In one searing performance after another, his brooding, anti-authoritarian, streetwise figures reflected the cynical mood of the times. After crossing to the other side of the law to portray the tightly-wound hippie cop of Sidney Lumet’s “Serpico” (1973), he continued to establish his tragic, hair-trigger persona as Sonny, the bungling bisexual bank robber exposed to the glare of the media as he holds hostages in Lumet’s “Dog Day Afternoon” (1975). Tucked amidst these career-making turns was an underrated turn in “Scarecrow” (1973), a road movie co-starring Gene Hackman, which removed the actor from his typical inner city environs. His breakdown after hearing from the bitter wife he abandoned that his son is dead – though the audience knows better – was one of his finest moments on screen.

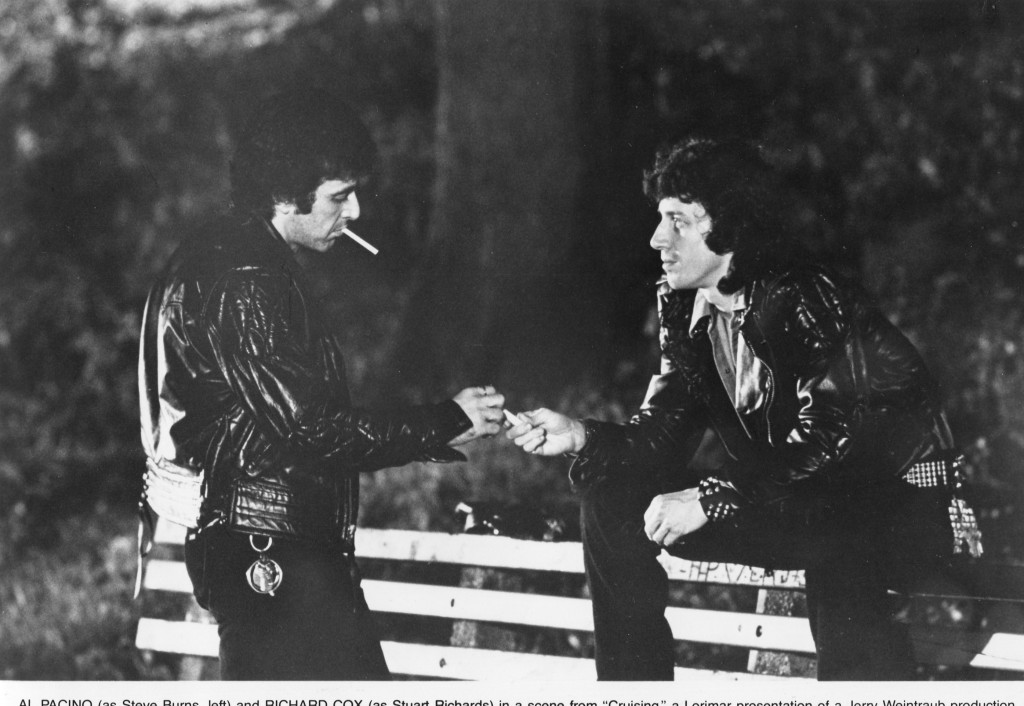

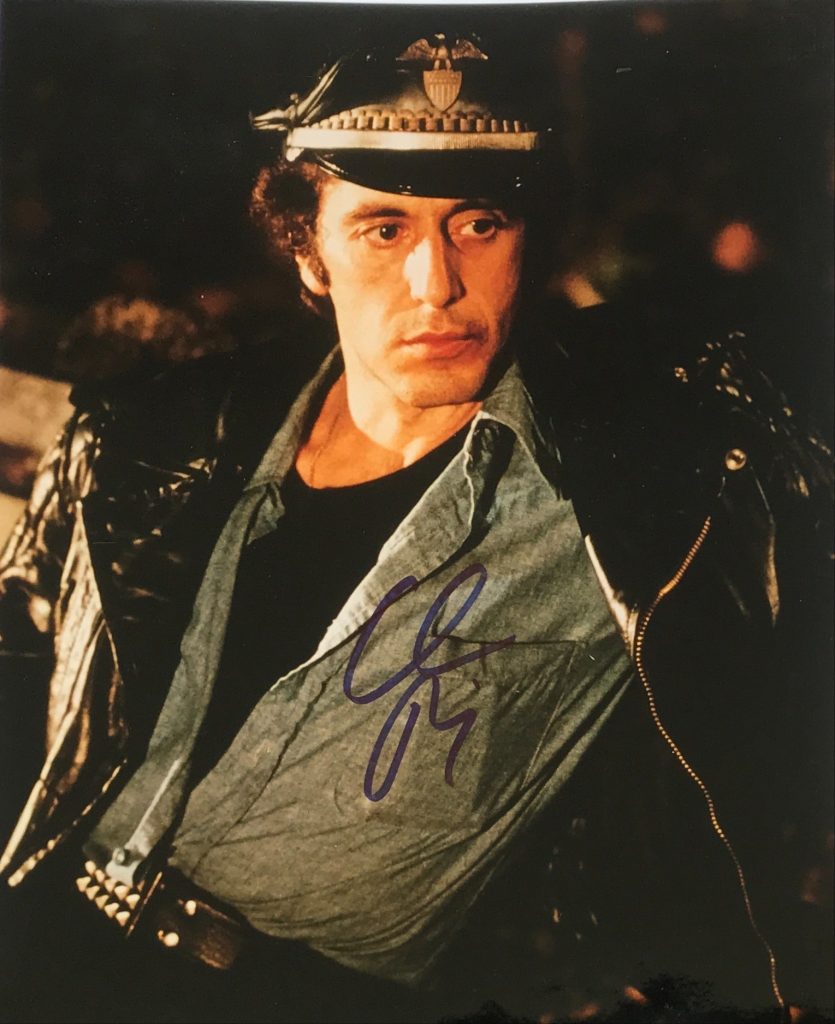

Pacino went on to make a series of false steps, starting with “Bobby Deerfield” (1977), which cast him as a sports car racer involved in a maundering romance with Marthe Keller. In “…And Justice for All” (1979) – which seemed like a move back to solid ground – Pacino displayed lots of angry flash, but little complexity or soul. His next film “Cruising” (1980), elicited either scorn or outrage from audiences and critics for its ridiculous, simplistic and hateful story of an undercover cop who infiltrates New York’s gay scene to find a killer and ends up being turned to the other side. “Author! Author!” (1982), Pacino’s first outright comedy, was a mildly enjoyable attempt to channel his intensity and energy in a new direction. But he returned to form – however outrageously – with his performance in Brian DePalma’s remake of “Scarface” (1983). Like the film itself, Pacino was deliciously over-the-top, but undeniably potent. Regardless of the negative criticism the film received, “Scarface” marked another seminal moment in the actor’s long career. Unfortunately, he followed up with the incredibly dull saga set in 1776, “Revolution” (1985). The nadir of his film career, “Revolution” forced Pacino to reassess his work onscreen.

Unlike many stage-trained actors who abandoned the theater when their movie stardom went into ascent, Pacino was never far from the footlights, often citing the thrill of working on stage by remarking to in 1999, “When you walk the wire in a movie, it’s not easy to walk, but it’s painted on the floor. But when you walk it on the stage, it’s 100 feet high without a net.” He won his second Tony Award for “The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel” (1977), reprising the starring role he had played in a Boston production earlier in the decade. Several times Pacino had essayed numerous Shakespearean roles, including the villainous Richard III and vengeance-minded soldier Marc Antony in a 1988 production of “Julius Caesar.” He also enjoyed a long association with David Mamet’s “American Buffalo,” playing Walter ‘Teach’ Cole from 1980-83 in a variety of venues, both off- and on Broadway. Though asked to revive the role in the 1996 film version, his loyalty to others previously connected to the project resulted in Dustin Hoffman assuming his signature role instead.

Pacino rediscovered his zest for film by co-directing and producing “The Local Stigmatic,” a pet project – adapted from a play he had once acted in – which he occasionally showed privately and continued to tinker with over the years. Harold Becker’s sexy, urban thriller “Sea of Love” (1989), provided the perfect comeback role – that of a streetwise cop-on-the-edge who falls for a murder suspect (Ellen Barkin at her most sizzling). Aided by an excellent, witty script by Richard Price, Pacino brought great depth to his loner, clutching at a second chance with the femme fatale – his impassioned reaction when one particular twist seemed to clearly indict Barkin – ranked high amongst his best work on screen. After an amusing parody of his previous gangster roles with an outlandish turn as Big Boy Caprice in “Dick Tracy,” he dusted off Michael Corleone one more time for the mediocre “The Godfather, Part III” (both 1990). He then poignantly played a short order cook recently released from prison opposite a game (albeit miscast) Michelle Pfeiffer in Garry Marshall’s “Frankie and Johnny” (1991).

Pacino was in top form in the 1992 adaptation of Mamet’s blistering “Glengarry Glen Ross,” picking up an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor for Ricky Roma, a hotshot real estate salesman competing with an office occupied by a bunch of down-and-out losers. That same year, he finally copped the elusive Oscar after eight nominations for his bravura star turn as the unabashed, “hoo-hahing” blind veteran cutting loose on the town in “Scent of a Woman,” a slight story ennobled by his electrifying portrayal. Similarly, his prison-sprung drug lord in “Carlito’s Way” (1993) showed his way with gutter-tough poetry, while his talent for various ethnic characterizations could be as riveting as ever. In Michael Mann’s “Heat” (1995), Pacino was finally paired opposite Robert De Niro, marking their first and long-anticipated appearance on screen together. Though both received high marks from reviewers, the lion’s share of the praise went to writer-director Mann for directing a tense, but rich crime thriller. That year also saw him age himself to beautifully render the grandfather in “Two Bits,” a Depression-era family drama too slow and delicate to realize its full potential.

Former NYC deputy mayor Ken Lipper scripted “City Hall” (1996), which cast childhood friend Pacino as a compassionate mayor embroiled in a corruption scandal, teaming him for the first time with another Bronx native, Danny Aiello. Though a descent into implausible melodrama compromised its compelling beginning, “City Hall” proved to be another that stood out as one of Pacino’s more intriguing films. Meanwhile, Pacino finished work after four years on “Looking for Richard” (1996), which he finally unveiled to great acclaim. Whittled down to two hours from more than 80 of raw footage, this documentary followed the actor-director in an exploration of Shakespeare’s first great tragedy,Richard III, while examining the relevance of The Bard to people in every walk of life. Pacino was back on Broadway as director and star of Eugene O’Neill’s “Hughie” in 1996 – his first visit to the NYC boards since his 1992 performances in “Salome” and “Chinese Coffee” – the latter of which became his next pet project as filmmaker. He finished shooting in 1997, but waited until 2000 to show “Chinese Coffee” at festivals.

If the 1980s had been inimical to Pacino’s talents, the 1990s turned out to be his most prolific. He delivered an atypical, introspective turn as a low-level gangster in Mike Newell’s “Donnie Brasc ” (1997), a tremendous story of two men who grow to admire one another. As far removed from Michael Corleone as one can get in the mob food chain, Pacino’s world-weary Lefty was tragic and pathetic, but also intensely human and real, inspiring the audience’s understanding and sympathy. The always fine Johnny Depp, in the title role, raised his acting level a notch in keeping with the high standards set by his co-star. Pacino returned to his old scenery-chewing tricks as a lawyer who happens to be Satan in “The Devil’s Advocate” (also 1997), proving yet again that it can be great fun watching a master pulling out the stops. Pacino toned it down for his next performance – one that depicted him at his intense best – playing rabble-rousing “60 Minutes” producer Lowell Bergman in Michael Mann’s “The Insider” (1999), an ambitious and intriguing drama that examined the state of journalism in the age of corporate malfeasance. Pacino closed out the decade in Oliver Stone’s “Any Given Sunday” (1999), playing a world-weary professional football coach battling younger players more enamored by money and fame than in playing the game.

Pacino’s next major role was as the sleep-deprived Detective Will Dormer in the crime thriller feature “Insomnia” (2002), writer-director Christopher Nolan’s English-language remake of Erik Skojdbjaerg’s 1997 Norwegian film, costarring Robin Williams and Hilary Swank. While the film received mixed reviews, the actors were roundly praised for their performances. Less appreciated was the Hollywood send-up “Simone” (2002), with Pacino playing a washed-up director who revitalizes his career by secretly creating a digital actress that perfectly executes his every command and becomes a major star. Not only was the movie’s fable-style tale wafer-thin, Pacino appeared out at sea with the material, giving one of his least memorable performances. Next up was “The Recruit” (2003) which saw him play a manipulative CIA instructor who recruits a young agent (Colin Farrell) to root out a mole inside The Company. Pacino followed with a supporting role in the dismal Ben Affleck-Jennifer Lopez comedy dud, “Gigli” (2003), reuniting with “Scent of a Woman” director Brest to play a federal prosecutor whose mentally disabled younger brother gets kidnapped.

Pacino rebounded with a stellar turn as Roy Cohn in HBO’s acclaimed adaptation of “Angels In America” (2003), a performance that earned him a Golden Globe for Best Performance by an Actor in a Miniseries or a Motion Picture Made-for-Television and an Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Miniseries or a Movie. In 2004, Pacino was able to bring one of his favorite Shakespeare plays to the big screen with director Michael Radford, playing the comically bitter Shylock in “The Merchant of Venice.” Although the anti-Semitic overtones of the play made it difficult to perform in modern times, Pacino effectively portrayed the moneylender’s claim for his pound of flesh, as driven by a realistic anger over the loss of his daughter to a Christian man. Pacino returned to his scenery-chewing ways in “Two For the Money” (2005), playing Walter Abraham, a sports wagering consultant who takes a former college basketball star (Matthew McConaughey) under his wing after learning that he has a knack for predicting games. After sitting out for much of 2006, sans a rare extensive interview on the long-running series “Inside the Actors Studio” (Bravo, 1995- ), Pacino joined the ensemble cast for “Ocean’s 13” (2007), playing a ruthless Las Vegas casino owner whose double-crossing of Danny Ocean (George Clooney) and company leads to his downfall.

Pacino kept a relatively low profile over the next couple of years, choosing to star in lower-budget movies that offered the actor more interesting opportunities. He first starred in “88 Minutes” (2008), a much-maligned thriller in which he played Dr. Jack Gramm, a forensic psychiatrist whose testimony against a convicted serial killer comes under question when new victims pop up on the eve of the convict’s execution. With just 88 minutes to live, Gramm hurries to find a copycat killer among a series of suspects. Almost universally panned by critics, the movie also flopped heavily at the box office. He next reteamed with Robert De Niro in “Righteous Kill” (2008), with both playing aging cops trying to hunt down a vigilante serial killer. Once again, Pacino suffered another critical and box office bomb. But the actor recovered nicely from the two debacles with “You Don’t Know Jack” (HBO, 2010), a well-received biopic in which he played the notorious Dr. Jack Kevorkian, a pathologist and right-to-die activist who was imprisoned for assisting upwards of 130 terminal patients to die with dignity. For his efforts, Pacino swept the Emmy, Golden Globe and Screen Actors Guild awards, winning all three trophies for Best Performance by an Actor in a Miniseries or Television Movie