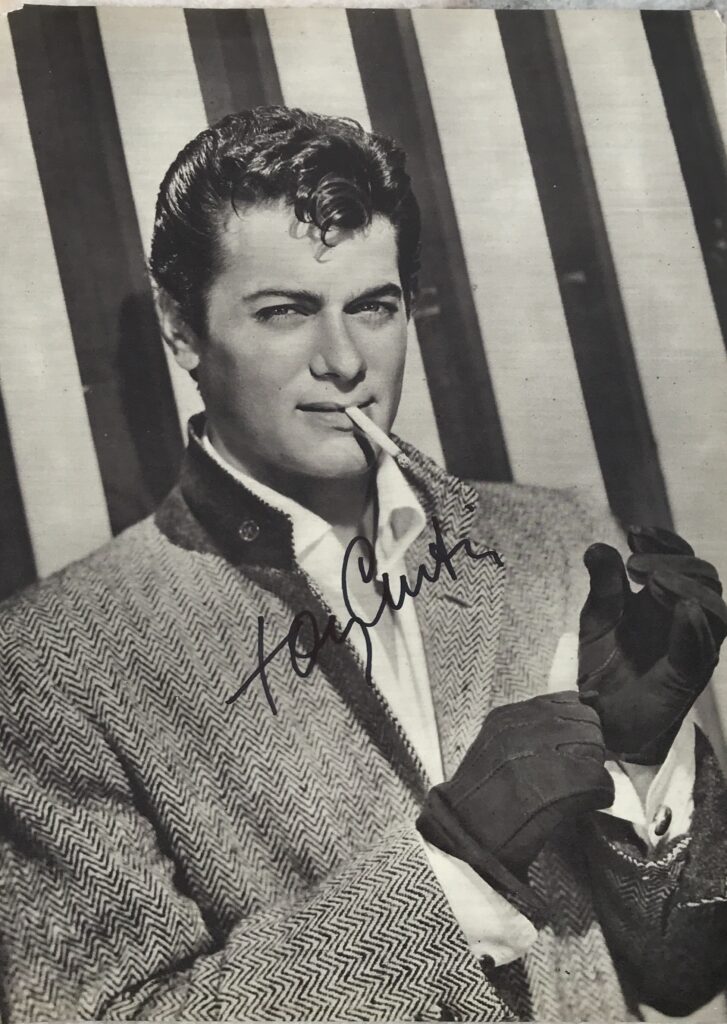

Tony Curtis was born 1925 in New York City. He was one of the giants of Hollywood cinema during the 1950’s and early 1960’s. He was under contract to Universal Studios alongside Rock Hudson and Clint Eastwood. Eastwood took a lot longer to break through into film than Curtis and Hudson. Among Tony Curtis’s many fine films are “Some Like it Hot”, “The Great Race”, “Houdini”, The Vikings”, “The Defiant Ones” and “Taras Bulba”, Tony Curtis died in 2010.

His “Guardian” obituary by Brian Baxter:

Born into a family of Hungarian Jews who had emigrated to the US, Bernard Schwartz – the boy who became the actor Tony Curtis – could scarcely have dreamed of the wealth, fame and rollercoaster life that awaited him. Curtis, who has died aged 85, starred in several of the best films of the 1950s, including Sweet Smell of Success (1957), The Defiant Ones (1958) and Some Like It Hot (1959). He enjoyed a long career thanks to his toughness and resilience (despite insecurities that demanded years of therapy).

He grew up in the Bronx, New York, the eldest of three sons. As a child, he was ill-treated by his mother, Helen, and spent time in an orphanage. One of his brothers, Robert, was a schizophrenic and the other, Julius, was killed in a traffic accident when Tony was 12. At school he became a member of a gang involved in petty crime, but he escaped into the Scouts. He endured poverty and the Depression and, in 1943, joined the US navy, serving as a signalman in the second world war.

He emerged, aged 20, into a world of opportunities – the first being postwar government funding for GIs to train for a career. He decided on acting (his father, Emanuel, had been an actor before becoming a tailor) and entered the Dramatic Workshop in New York. He took the lead in a Greenwich Village revival of Golden Boy, written by Clifford Odets, and was spotted by a studio talent scout and offered a contract by Universal. He first chose Anthony Adverse as his professional name, inspired by the eponymous hero of a novel by Hervey Allen. A casting director persuaded him otherwise, so he kept “Anthony” and added “Curtis”, anglicising a common Hungarian surname.

Like the far grander MGM, or the Rank Organisation’s “charm school” in the UK, Universal had a policy of training promising talent. The prerequisites were good looks and ambition. Curtis had both in abundance. He made his uncredited film debut in Robert Siodmak’s Criss Cross (1949), as a gigolo who dances with Yvonne de Carlo, watched by the male lead, Burt Lancaster, who later played a significant part in Curtis’s career.%

After this 30-second screen exposure, he notched up 10 appearances in two years, including the westerns Sierra and Winchester 73 (both 1950). He later said that the performances were “guided by testosterone, not talent”. He and the other Universal proteges, including Rock Hudson, were trained in acting, fencing, riding and dancing. By 1951 he was considered ready for the lead in a swashbuckler, The Prince Who Was a Thief, and was married to the starlet Janet Leigh, who later appeared alongside him in films including The Vikings (1958).

Curtis went on to star in a slew of second-grade movies, such as Son of Ali Baba (1952) and Houdini (1953). His big break into A-features came when Lancaster chose him as his co-star in Trapeze (1956). They made a convincing pair of high flyers, and the glossy movie, directed by Carol Reed, was an international hit.

After playing the lead in Blake Edwards’s Mister Cory (1957), Curtis joined Lancaster again in Sweet Smell of Success, produced by Lancaster’s company. A superb screenplay, co-written by Odets, was the launchpad for Alexander Mackendrick’s vividly achieved portrait of obsession and betrayal. Lancaster played the reptilian, all-powerful, New York columnist besotted with his sister. Curtis was Sidney Falco, an unprincipled press agent in thrall to (and fear of) the man who could make him king of the jungle, and willing to sell his pride and soul for the title. It gave Curtis the reviews and credibility for which he had yearned.

Routine movies followed until The Defiant Ones gave him his first and only Oscar nomination, for best actor. This modestly liberal story – an archetypal Stanley Kramer film – proved important for Curtis, who insisted that his black co-star Sidney Poitier share top billing. It was significant as a commercially successful film, making a plea for racial tolerance, directed and acted with force and integrity. Although he did not get the Oscar (which went to David Niven for Separate Tables), Curtis was soon to receive a greater prize – the second great movie of his career, Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot.

After this movie, Curtis’s career declined in quality, if not quantity. Edwards capitalised on his two best roles and cast him opposite his hero Grant in the bright and funny Operation Petticoat (1959), where he played a jokey variation of Sidney Falco. The following year he was in heady if duller company in Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus, playing Antoninus, the handsome slave who flees from the overtures of his master, Laurence Olivier.

Appearing alongside Jack Lemmon and – less happily – a difficult Marilyn Monroe, Curtis enjoyed three sublime manifestations in the film. First, as one of two jazz musicians who flee from gangsters after witnessing the St Valentine’s Day massacre in Chicago in 1929. Second, in drag as a member of the all-girl band which provides his camouflage. And last as a fake oil millionaire – out to seduce Marilyn – played as a wonderful homage to Cary Grant. “Marilyn was an enigma,” he later said. “She was very difficult to read. Marilyn and I were lovers in 1949, 1950, 1951 … It was an important relationship for me.”

He then made two films with the director Robert Mulligan – The Rat Race (1960) and The Great Impostor (1961) – and starred in The Outsider (1961) as Ira Hayes, the Native American hero of the battle of Iwo Jima during the second world war. As Curtis’s career progressed, his marriage to Leigh – who had sacrificed her work for him and their children, Jamie Lee and Kelly – began to disintegrate. They divorced in 1962, and the following year he married the actor Christine Kaufmann, with whom he had two daughters, Alexandra and Allegra. He had some success with Jerry Lewis in the comedy Boeing Boeing (1965) and rejoined Edwards on The Great Race (1965), parodying his charismatic persona with a cocky grin and effortless charm

He had less success with Mackendrick’s Don’t Make Waves (1967), a slow-burn comedy which suffered from studio interference. He then made a strenuous effort for critical acclaim with his role as the serial killer Albert DeSalvo in The Boston Strangler (1968), flashily directed with use of a split screen. More routine films, and a lucrative two-year stint in the television series The Persuaders (1971-72), kept him busy, as did his increased interest in his painting, art collecting and writing. He married the model Leslie Allen in 1968 (having divorced Kaufmann the year before) and dedicated his frantic, exhausting novel, Kid Andrew Cody and Julie Sparrow (1977), to her. He had two sons with Allen, Nicholas and Benjamin.

Occasional meaty parts continued to come his way, including the eponymous gangster in Lepke (1975) and the fading, impotent movie star in the lugubrious The Last Tycoon (1976). He returned to the stage in the 1979 Los Angeles run of Neil Simon’s play I Ought to Be in Pictures. His best work on television was in The Scarlett O’Hara War (1980), as the producer David O Selznick, and the series Vega$ (1978-81). But he had lost his comic lightness of touch and decent parts were rare, although he relished his role as the Senator in Nicolas Roeg’s Insignificance (1985). He was admitted to the Betty Ford clinic for treatment for his alcohol and drug abuse, and his other 80s credits, such as Lobster Man from Mars (1989), revealed his diminishing standing.

Curtis and Allen had divorced in 1982, and he married the lawyer Lisa Deutsch in 1993. They divorced the following year. Curtis talked of quitting show business to open an art gallery in Europe. There were also rumours of a return to the stage opposite Lemmon and of a second novel. In the event, he returned to big and small screens in a desire not to earn money but to keep working. His autobiography was published in 1993, and in the mid-90s he suffered personal trauma as he underwent heart surgery and his son Nicholas died of a heroin overdose.

He married Jill VandenBerg, more than 40 years his junior, in 1998, and said he had never been happier. Curtis relished being remembered for the Mackendrick movies above all, and for his quirky cameos (often uncredited) in numerous films – not least as the “voice” in Rosemary’s Baby (1968). But he remained bitter about the lack of official recognition for his best work, convinced that he lost out on an Oscar for The Defiant Ones because of his “pretty boy” image. On the occasions I met him at his London home in Chester Square, Belgravia, he was always interested in showing his work as an artist. His paintings have been exhibited in Europe and the US, at galleries including the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Curtis is survived by Jill, his daughters Jamie Lee, Kelly and Allegra (who all became actors), another daughter, Alexandra, and his son Benjamin.

• Tony Curtis (Bernard Schwartz), actor, born 3 June 1925; died 29 September