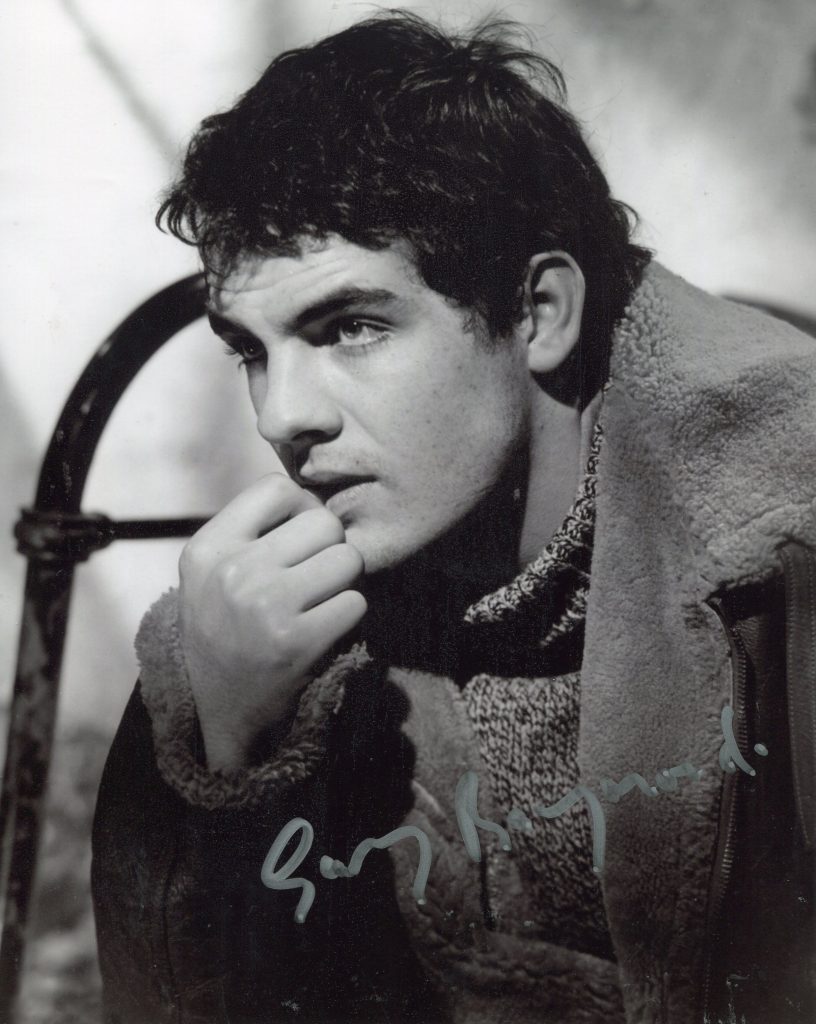

Michel Ray was born in 1944 in England to an English mother and a Brazilian father. He made his film debut in “The Divided Heart” in 1954. In 1956 he went to America to make “The Brave One” and “The Tin Star” amongst others. In 1962 he was featured in “Lawrence of Arabia”. He ceased acting in 1964 and became a stockbroker.

His IMDB entry:

He was born into a wealthy family having an English mother and a Brazilian father. He was educated in Switzerland where he learnt to ski. His parents were friends of producerMichael Balcon who was looking for a boy who could ski for his 1954 film The Divided Heart (1954). Young Michel fitted the part perfectly and started a film career which culminated in the role of Faraj in Lawrence of Arabia (1962).

This project took eighteen months and caused Michel to look at the affect film work was having on his education. He decided to quit acting. He subsequently attended Harvard where he read business studies. After university he joined White Weld & Co moving on to NM Rothschild and Credit Suisse First Boston. In his London city career in investment banking he made his first millions.

In 1995 he joined Nikko Securities and in 1998 became the first non-Japanese member of the main board. Meantime he had continued his passion for winter sports and was a member of the British Olympic ski team at the 1968 Winter games in Grenoble, France

He was in the team again in ’72 and ’76 competing on these occasions in the luge. He had also married a childhood friend Charlene, daughter of Alfred “Freddie” Heineken. Her mother was Lucille Cummins daughter of a Kentucky Bourbon maker.

Her father Freddie died in January 2002 and left his controlling interest, 50.05%, in the Heineken brewing empire to the couple. It is estimated at three billion pounds sterling or four point two billion dollars. Michel’s life story is more glamorous than many a Hollywood fiction.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Crombie

MailOnline” article on Michel Ray in 2012:

As a teenager, Michel de Carvalho was living every boy’s fantasy. While his friends sat in school, 17-year-old Michel was a movie star, with a coveted role in Sir David Lean’s epic, Lawrence Of Arabia.

Between breaks in filming, he caroused through the fleshpots of Beirut with Hollywood stars Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif, pursued by hordes of adoring females. The film won seven Oscars and would go down in cinema history. Michel, using the stage name Michel Ray, seemed destined for fame.

Many child actors would let the experience go to their heads and veer off the rails, eventually disappearing from view. But Buckinghamshire-born Michel has continued to thrive and enjoy life to the full.

Now aged 68, he is still living out a male fantasy – as a financier with a £5.5 billion fortune and limitless supplies of beer. He did it by deciding to abandon acting on the set of the classic film so that he could enrol at Harvard University.

He also went on to compete in two Winter Olympics as a skier and tobogganer. And he married the love of his life, Charlene Heineken, now 58, the daughter of the late brewery magnate Freddie Heineken. In 2002, the couple inherited the £4 billion controlling stake in the Heineken empire.

The shares have surged and with the recent acquisition of the Tiger beer brand the group’s value has increased by more than £1 billion.

Now chairman of Citi Private Bank’s business in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, Michel commutes between London, Washington and Holland. ‘I’ve always believed work hard, play hard,’ he says. ‘Life has never been boring – luckily.’

Approaching their 30th wedding anniversary, the couple undoubtedly lead an enviable life, but their lifestyle has never been ostentatious.

Their wealth eclipses that of Sir Philip Green and his wife Tina, as well as the Bransons and the Rausings, but the couple have never appeared in glossy photo spreads or hosted lavish public parties.’I partied in Beirut with the greatest actors of the age’

Instead, they concentrated on raising their five children in England, away from the glare of publicity. But later this month they may be tempted out for a rare appearance – to celebrate the re-release of the film that could so easily have launched Michel into a Hollywood career 50 years ago.

In the biopic of T. E. Lawrence, Michel played Farraj, one of the First World War hero’s two teenage followers. ‘They offered me the choice of the two roles – one dies in quicksand, the other is blown up,’ Michel recalls, speaking exclusively to The Mail on Sunday about his extraordinary life.

‘I said, ‘‘Which one lasts longer?’’ And they said the one that gets blown up by a detonator near the railway line. So I took that one, because it paid more.

‘Now whenever I tell anyone I was in Lawrence Of Arabia they say, “Oh, were you the one who went down in the quicksand?” And no one can ever remember the other one.’

Sands of time: As a child actor, Michel de Carvalho played the role of Arab boy Farraj opposite Peter O’Toole in the classic film Lawrence Of Arabia in 1962

In fact, Michel appears in one of the film’s most iconic scenes – as he and Lawrence stride into the officers’ mess in Cairo to announce the audacious capture of Aqaba. ‘We’re thirsty,’ Lawrence announces, dusty and dishevelled. ‘We want two large glasses of lemonade . . . there’s been a lot of killing, one way or another.’

During the 18-month shoot in 1961 and 1962 Michel became acquainted with some of the most talented actors of his age – as well as the countless women who pursued them. ‘The parties happened on rest and relaxation days in Beirut. Quite often I went with Peter O’Toole and Omar Sharif – and that was super fun,’ he says.’At school I got so much fan mail’

Camel-riding proved more of a challenge. ‘In the beginning it wasn’t pleasant,’ Michel says. ‘You are sitting mostly side-saddle, with the hump coming up in the middle and you’re not really supposed to grip it. On one occasion I was on a camel which suddenly saw its stable – and it bolted for home, which was terrifying.

‘Years later, friends of mine had a 50th birthday party in Egypt. We went up and down the Nile. On one day they organised a camel race. Needless to say, I won.’

‘We couldn’t possibly discuss the fun in an elegant Sunday newspaper… they were the superstars and I was the bag carrier. But even superstars can only handle so much. And then the bag carrier…’

Looking back, Michel appears incredulous at his teenage decision to give up acting on the set of one of the greatest movies. ‘I said – using a huge swear word – ‘‘What am I doing here in the Arabian desert with all these funny people, superstars, Anthony Quinn, Peter O’Toole, Omar Sharif, Jack Hawkins and the rest?’’ Where are my friends? This is a weird life. And then, almost simultaneously I became self- conscious about acting. And I just couldn’t get over my self-consciousness. It was the worst decision I ever made.

Multi-talented: Michel de Carvalho was part of the British Olympic luge team. Here he is pictured at Heathrow Airport before a flight to Japan, where he took part in the Winter Olympics at Sapporo

‘I never usually talk about Lawrence Of Arabia, but I was discussing it with someone last night and they said it wasn’t the worst decision because where would I be today? Some ageing B actor, looking for TV adverts.

‘But I should have stretched out the acting career a bit – maybe until 30.’ Born to a Brazilian diplomat father and an English mother in Gerrards Cross, Buckinghamshire, in 1944, Michel fell into acting at the age of ten. His father had died when he was very young and his mother married again, to a wealthy leather merchant.

The family entertained many illustrious figures to dinner in their London home – one was the famous producer Sir Michael Balcon, who needed a young boy who could ski, to star in his film, The Divided Heart. Initially Michel’s mother, Annie, was opposed to the idea of her son appearing on screen. He recalls: ‘But Sir Michael said it was only three months and who knows what will happen – this door has opened, why would you close it?’

Michel was a hit and film offers flooded in. Using his two Christian names as a stage name, Michel Ray was the Daniel Radcliffe of his day – going on to great acclaim in films such as The Brave One and The Tin Star.

Between films, Michel attended a boarding school in Switzerland, honing a gift for languages and developing his passion for skiing.

Rich lives: Michel de Carvalho with his wife Charlene, the Heineken heiress

Aged 17, his star reached a peak with Lawrence Of Arabia. ‘I had massive attention at school,’ he says. ‘I got so much fan mail. I never get that any more – as a banker, you get hate mail.’

Five years after he walked away from acting, just as he was about to take up a graduate place at Harvard Business School, his life took another twist when he was offered the chance to become a member of the British ski team at the 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble, France.

‘It wasn’t so much for my skill as for my ability to pay the plane fare,’ says Michel modestly.

His mother was not keen on the idea. She had been relieved when he gave up acting and wanted him to get serious about making a living. ‘I wish I had kept the telegram she sent,’ he says. ‘Every second word was “bum”. It said, “From film bum to ski bum – if you make this totally stupid decision, you will be completely cut off.” So I made the completely stupid decision.’

He delayed taking up his place at Harvard to compete. ‘I told a huge porkie pie to Harvard – I can’t tell you what it was in case they take away my diploma.’

His mother need not have worried. He duly graduated from Harvard and embarked on a career in banking. But he had just begun his second job, at NM Rothschild, when he was asked to join the 1972 GB Olympic team once again – this time in the luge, the fastest and most dangerous style of tobogganing. Nervously, he asked his new boss for time off to compete in Japan. ‘I was sitting at my desk and the internal phone rang. A voice said, “Will you pop up?’’ It was Eddie Rothschild, the chairman of the bank.

‘I went upstairs and Eddie rummaged in his pockets, pulled out £200 – which was my weekly salary – and said, “Let me remind you, young man, in this bank, England comes first.” ’

Michel competed in the luge with his best friend Jeremy Palmer-Tomkinson – the uncle of socialite Tara Palmer- Tomkinson. ‘In the first week of training, my entire body was dark blue,’ he said. ‘When you are in the double luge you really are just fodder – I was the little guy and Jeremy was the big heavy guy on top. In the Japan Olympics, we were really just clowns.’

In 1983, when he was in his late 30s, Michel married Charlene Heineken. ‘Our families both had houses in St Moritz,’ he says. ‘I was ten years older than her so it wasn’t what you would call love at first sight – certainly not on her side.’I met the girl of my dreams, complete with free beer’

‘I always drank Heineken. But the problem was Heineken was the most expensive beer. So when I met my wife I thought, “This is fantastic, I’ll have free beer.” I didn’t realise then that marriage is not just about free beer.’

The couple honeymooned in the Caribbean but suffered a shock on their return. In November 1983, Charlene’s father was kidnapped in Amsterdam and held for ransom for three weeks.

‘It was a baptism of fire,’ says Michel. ‘I was just not prepared for something like that. My father-in-law had no other family but my mother-in-law, my wife and me. Luckily, it all ended well. The ransom was paid and the kidnappers all went to jail.’

In 2002, Freddie Heineken died and Charlene inherited her father’s stake in the family business – which transformed her and Michel, overnight, into one of Britain’s wealthiest couples. Today, Charlene and Michel still play a key role in the business.

Sitting in the desert with Peter O’Toole, Michel could little have dreamt how his life would turn out. ‘I never planned my life,’ he says. ‘The good lord has been kind. If you have a bit of luck, you can do quite a lot. But looking back, it was probably a mistake quitting acting.

‘ Looking back, someone should have said to me, “No, stay with that.” ’

The 50th Anniversary 4K Restoration of Lawrence Of Arabia is in cinemas across the UK from November 23. The Empire Leicester Square will have special preview screenings from next Saturday

Publicity portrait of Glynis Johns for Mad About Men (1954) © Group Film Productions. Preserved by the BFI National Archive

Publicity portrait of Glynis Johns for Mad About Men (1954) © Group Film Productions. Preserved by the BFI National Archive