IMDB entry:

Brittish Actors

IMDB entry:

Simon Hattenstone’s “Guardian” article:

You want laddish? Russell Tovey‘s your man. In the beautifully observed TV sitcom Him & Her, he plays Steve, an unemployed procrastinator whose ambitions stretch to drinking, watching porn and shagging his girlfriend. As bewildered werewolf George Sands Junior in the supernatural drama Being Human, he makes his girlfriend pregnant but just wants to be one of the boys. In the new TV whodunnit What Remains, Tovey’s Michael is again preparing, reluctantly, to be a father. He tends to play boy-men who find themselves in grown-up situations against their better judgment. He often gets the girl, but you’re never sure why, or whether he’ll keep her. There are few actors who exude such irrepressible down-the-pub blokeishness. Tovey is also one of Britain’s few out gay actors.

We meet at a park in London’s Soho. Tovey is accompanied by his gorgeous French bulldog, Rocky, or the Rock if you know him well. There’s something instantly likable about both of them. Rocky introduces himself by giving me a thorough face wash, and Tovey starts telling me why he didn’t join his parents’ coach company (they own the Gatwick Flyer, which runs between Essex and Gatwick airport), how he got into trouble at school time and again, and how his ambition as a nine-year-old was to be a father by the time he was 14.

Tovey grew up in Billericay, Essex, to parents who worked all hours to build their business. He had one of the highest IQs in his year at school, but applied himself only to things that interested him. He was easily bored, and liked to make people laugh. That’s how he got into trouble. He never did anything really bad, just daft or disrespectful – like the time he called his French teacher sweetheart. “I got escorted by the head of PE and a security guard to the office of the deputy headmistress, Mrs Palmer.” Mrs Palmer asked if he would call her sweetheart, and he said, only if he knew her better. Tovey was suspended for two days. His next suspension was for eating cake. Well, if we’re being pedantic, for following girls into the toilet after they had refused to give him some of the cake they had made in Home Economics, and stealing it from them. “I turned round with a mouth full of victoria sponge and there was Mrs Palmer.”

Then there was the time he was thrown out of Barking & Dagenham College. He left school at 16, was doing a BTec in performing arts, and was due to be in the chorus of the college production of Rent when he was offered a part in a commercial. “They said, if you take this we’re not going to invite you back, and also if you leave you’ll never work again. Anyway, I left.” The college now cites him as one of its famous former students.

Tovey says he spent one school holiday just watching movies, and that was that. “Dead Poets Society was a big one, Home Alone, Stand By Me, Labyrinth, things like that. I thought the films were brilliant, but more than anything I wanted to be a part of them rather than just watching.”

His first part was as an extra in The Bill in the last year of junior school. He played a traveller who shouted “Oi” and threw a football at a police officer. It wasn’t much but he loved it. He started making money while at school, but says nobody noticed because most of the children had loaded parents anyway. Tovey’s mother always warned him not to show off about his work, so he kept quiet. “Mum said, if people ask you about it, it’s fine, but don’t boast, don’t talk about anything. So it’s always felt very private, what I do. If you’ve seen me, great, and if you want to talk about something, brilliant, but I’m not going to come in and say, ‘Did you see me on this, what did you think?’ That’s just not in my nature… Oh my God! Look at that, he’s trying to hump you!” His voice rises a couple of notches in shock. “Rocky! Don’t do that! What’s wrong with you?” He gives Rocky a severe talking to, apologises on his behalf, then tells me it’s not easy being a French bulldog. “If you’re human and you feel sexed up, you can do something about it. But if you’re a dog I don’t think you can, can you?” He looks at Rocky’s underbelly. “Rocky can’t reach his,” he says sympathetically.

A holidaying Brazilian family walk over and ask what breed Rocky is. It’s funny, Tovey says when they’ve gone, he worried that Rocky might make him more recognisable, but it’s worked the other way – strangers approach him all the time, ask about the dog, have a few strokes and toddle off without so much as a hint of, “Aren’t you …?”

From 11 onwards, Tovey acted regularly in professional productions. But it was only in his early 20s that he made his name with Alan Bennett’s The History Boys, alongside Dominic Cooper and James Corden. Tovey was already out, and Bennett could happily have cast him as Posner, an angsty gay boy infatuated with one of his fellow students. But somehow it didn’t seem right; Tovey was always going to be more convincing as sporty, plain-speaking Rudge, who is given the brilliant line: “How do I define history? It’s just one fuckin’ thing after another.”

In fact, Tovey auditioned for Dakin, the handsome smoothie eventually played by Cooper, even though he knew he was unlikely to get the part. “I had loads of spots, but I went in and said, look, I want to play this part. Dakin was meant to be the lead, lothario, sex object, and nobody was going to lust after me, this spotty, pasty, big-eared thing. But Alan Bennett really liked me and he thought, well, he obviously wants a bigger part, so he wrote up the part of Rudge for me.” Tovey’s skin problem almost led to him quitting the production. “My skin was so bad, I thought, I just want to leave. It was really affecting me psychologically. You go into makeup and they’d paint each spot. It was self-esteem-crushing. Horrible.”

Tovey has perfect skin today, but he has had to work at it with medication. “I still feel I’m going to wake up any moment and my skin’s going to break out all over. If I get one spot now, this absolute cloud comes over me.”

Despite this, he was never exactly lacking in confidence.”I thought I could charm people. I never felt I was attractive to women. I felt I was attractive to men when I was growing up. And even now, if a woman fancies me, I find that a bit alienating. A bit like, ‘You’re sure you’re not taking the piss?’ Because, having the skin, it always felt, I don’t know, not good enough. Whereas with men it was a bit like, it’s rough, it’s fine, don’t worry. Do you know what I mean? Growing up having sticky-out ears, pasty skin, then going through teenage years with spots.” Did he consider having his ears pinned back? He looks appalled. “No. I’ve never felt anything apart from love for my ears. My eldest nephew’s got them now, and he’s so proud of them because he’s got his uncle Russell’s ears. They’re my trademark.”

At school he always had girlfriends. It was only when he got into his mid-teens that he realised they didn’t do that much for him, that he was attracted to boys. “Looking back, I always knew. But you don’t reallyknow till you get to a point where you go, oh, that’s what makes me happier.” At 18, he came out to his family and his father tried to talk him out of it. “My dad was of that generation where it’s changeable if you get it early enough.”

How would he have changed you?

“Hormone therapy or shock treatment, all of these horror things that you watch. You see, they had all this Aids thing. It was all, ‘Don’t die of ignorance.’ My nan thought being gay was a disease. It’s just a generational, educational thing. And Dad was like, ‘I wish you would have told us sooner because we would have done something about it.'”

Were you surprised by the reaction?

“No, I was prepared for it.”

Was it based on prejudice or fear?

“Not knowing. Not knowing anybody else who is gay, not experiencing it, hearing of people dying of Aids and seeing, say, Larry Grayson on TV and thinking, that’s it. Seeing gay men appear in stories in which they were miserable and sad. And I think he felt sad and worried for me, that I’d have a terrible life if I made this choice. And he thought it was a choice, because being straight is so natural, why would you want to be anything different from that?”

It’s touching how determined Tovey is to understand his family’s fears of his sexuality.

“You want your kids to be perfect and at that time it felt like it was an imperfection. Whereas now a lot of people are like [enthusiastic voice], ‘Are you? Cool! Well, make sure you look after yourself.’ It seems like it’s a different time. I sense that with younger generations, when they have after-school clubs where they talk about being gay. I meet a lot of kids who’ve come out at school, and I’m like, ‘What! You came out at school! Did you get bullied?’ ‘No!'”

He smiles. He’s just remembered something that amuses him. “My mum used to think it was the pill that made you gay. There was too much oestrogen in the water, and people started taking the pill in the 60s and it made everybody gay.”

On screen, Tovey is forever snogging girlfriends or flashing his bum. Does he enjoy his sex scenes? “I have quite enjoyed my sex scenes.” Hurrah! He’s the first actor I’ve ever heard admit that.

“I don’t get embarrassed by sexual parts. I want to protect the girl. Nine times out of 10, girls are more embarrassed.” He thinks about it. “You know what? Actually, if I was doing a gay sex scene, I’d probably feel really embarrassed.”

Do women playing his love interest see him as a challenge? “No, because most of my leading ladies are in relationships, and their partners are thrilled when I get cast with them in these intimate roles because I’m not a threat. I think if I’d been straight I would have slept with a lot of actresses by now and there’d be a lot of broken relationships.”

Really? He laughs. “Is that quite an egotistical thing to say? It’s just the leading man/leading lady thing, which happens again and again. You’re playing being in love and you fall in love.”

Tovey says he’s looking forward to his next part in What Remains because his character is a bit darker than normal. There’s also a new series of Him & Her coming up, which he loves. (“It feels very Pinteresque to me. If I wasn’t in it, I’d watch it religiously.”) And he’s busy writing: he’s written three plays so far, which have been read at the Soho theatre and National theatre studio but have yet to be performed. He describes them as being “about people in the margins”.

I ask Tovey if there was one thing he could change in the world, what it would be? “Right now? I feel, as a taxpayer who’s self-employed, I hate the fact that you have to pay on your projected earnings for the following year. Can’t we get rid of that? Let me earn it, then I’ll pay it back to you. Don’t say, well, you owe us half of what you might earn next year. That’s it. Haha!” Blimey, he sounds like a proper Tory Essex boy. “Tory? No, absolutely not. I was in the House of Lords recently for the whole debate about gay marriage. It was incredible, just sitting there watching all these really old white, middle-class, crusty men talking about how they thought it was wrong. They feel very removed from what is happening in the real world outside.”

It’s interesting that Tovey says it’s so much easier to come out today than when he was a boy. If anything, among actors, the opposite appears to be true. Whereas years ago the likes of Ian McKellen, Anthony Sher and Rupert Everett came out (admittedly in middle age or when already established), there are few openly gay stars of Tovey’s generation. “Well, there’s the guy who plays Spock in the new Star Trek film, Zachary Quinto.” He tries to think of others, but fails.

The fact that you can name only one gay actor in Hollywood suggests there is still a taboo, I say. What about well-known young British actors? He racks his brain. No, no one he can name – not publicly, anyway. “I assume there are a few. Whether they are out or not is not for me to say.” That is crazy, I say. “Well, I hope it’s changing… I’ve found out over the years that the conversation about casting me has come up: would it affect the show and the audience if I’m a gay man playing a straight character? These conversations are being had still.” Everett has said that coming out crippled his career, that now he’s largely restricted to playing gay. Perhaps the difference for Tovey is that he was out from the start, and because he didn’t make much fuss about it, nor did anybody else. As for the viewing public, he says they couldn’t care less. “You’ve got to remember that of the millions who watch TV, most people don’t give a fuck about your private life or know who you are.”

Tovey says he is keen to play a gay man, but there are very few good parts. “I really want to do it properly, with something that is clever and moving everything forward rather than covering old ground. Not someone who’s gay and miserable, dying of Aids, secluded, a bit weird. I want to play someone who’s normal and just happens to be gay.”

Shortly after I meet Tovey, the actor Ben Whishaw issues a statement saying he is gay and happily married. I contact Tovey to ask what he thinks. “I’m just happy he is a well-adjusted dude and out now, another good role model who isn’t defined professionally by who he wants to share his personal life with.”

Tovey has been with his boyfriend for four years. They live together, are very happy, and that’s all he wants to say because it’s private. He’s wearing a couple of rings. I ask about their history. The one on his middle finger, he says, is his father’s old ring and he never takes it off. And the other? He blushes. “It’s just another ring. It’s on that finger… which means something. I’m not married or anything. It’s just a symbol of commitment, I suppose.” Yes, he says, he would like to get married, and still fancies being a father.

Tovey says he always knew it was important for him to be open about his sexuality. Why? Simple, he says. “I love my personal life and having a social life. And I didn’t ever want to have to compromise. I could imagine being at this stage now and having skeletons in the closet, and you sitting here going, ‘So have you got a girlfriend?’ and me saying, ‘I’ve not got a girlfriend at the moment, I’ve not met the right girl, there’s a few people around.’ And in my head going, I’m going back home to my boyfriend in five minutes.” He pauses. “D’you know what I mean? I just can’t be arsed with that.”

The above “Guardian” article can also be accessed online here.

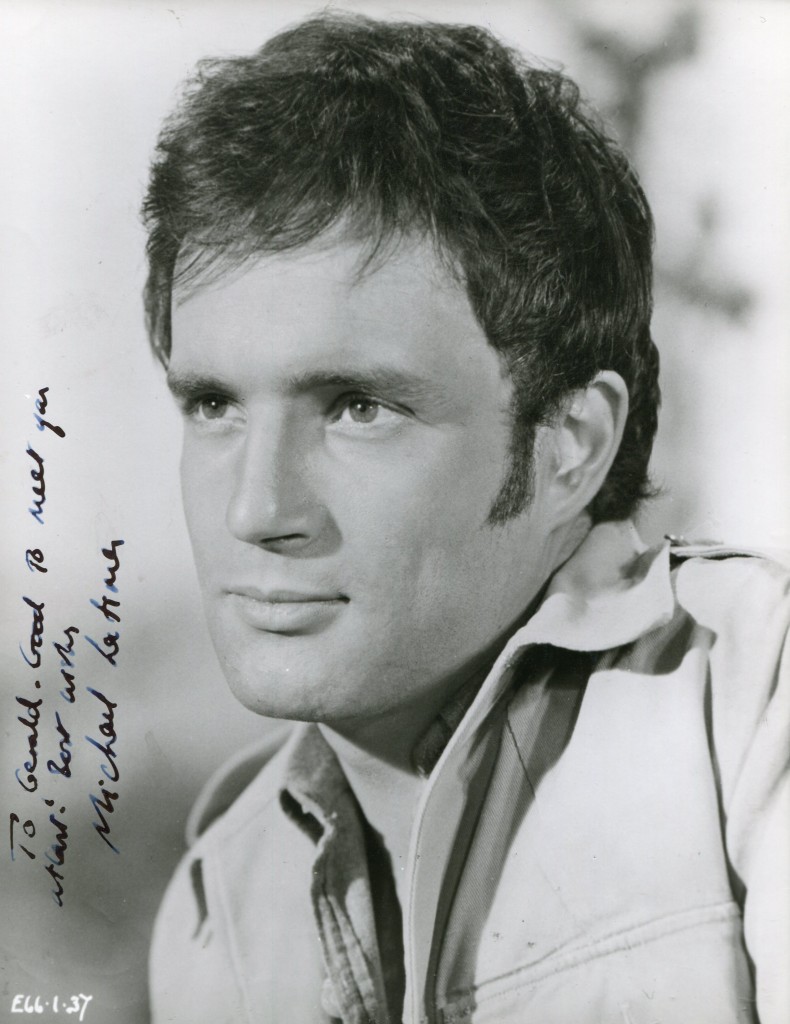

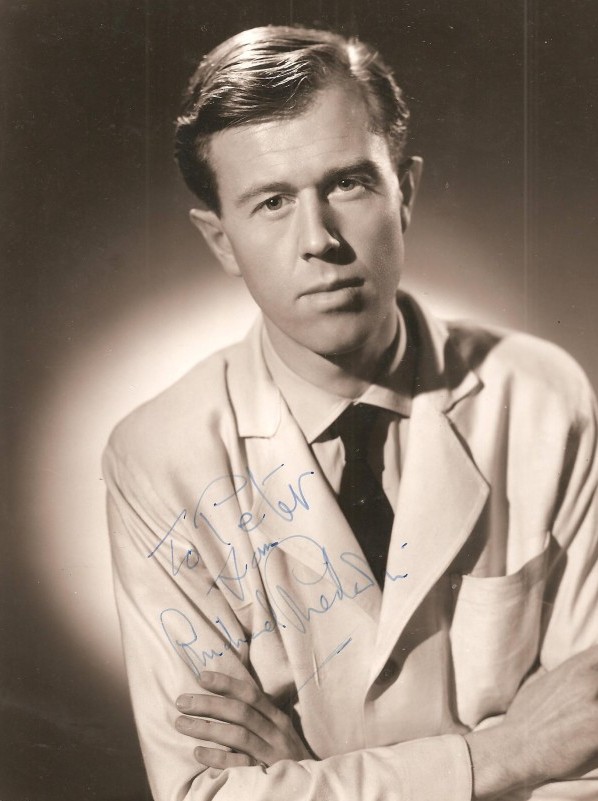

Michael Medwin was born on July 18, 1923 in London, England as Michael Hugh Medwin. He is an actor and producer, known for The Duchess (2008), Three Live Wires (1961) and Scrooge (1970).

Best known for countless character roles in films and as the wide-boy Corporal Springer in the highly acclaimed 1950s TV series The Army Game, the actor Michael Medwin, who has died aged 96, also enjoyed success in other areas of show business across seven decades.

He began his career in the theatre and co-scripted several of the films in which he appeared, including My Sister and I (1948), Children of Chance (1949) and the musical Scrooge (1970), in which he was nephew to a Scrooge played by Albert Finney. He founded a production company, Memorial, with Finney and produced several British classics, including Lindsay Anderson’s If… (1968).

Memorial’s first film, Charlie Bubbles (1968), directed by Finney, was a quirky comedy drama about a novelist returning to his northern roots. It featured a miscast Liza Minnelli and, because of its fragmented narrative, enjoyed only modest commercial success. However, it boasted fine technical and artistic credits that characterised the company’s subsequent productions.

They moved on to the spirited and subversive If…, co-produced and directed by Anderson. This powerful study of rebellious youth became a key movie of the decade and Memorial’s most significant production. Others included Bill Naughton’s Spring and Port Wine (1970), which had originated on radio, and Stephen Frears’s spoof thriller Gumshoe (1971), a stylish success that starred Finney as the eponymous detective.

Medwin again collaborated with Anderson on the satire O Lucky Man! (1973) and a year later worked in the US co-producing and playing a cameo in Ivan Passer’s uneven comedy, Law and Disorder. There was a gap until Memoirs of a Survivor (1981), an ambitious attempt at filming Doris Lessing’s novel. It failed commercially and proved to be Memorial’s swansong.

Medwin was born in London, and adopted by Dr Mary Jeremy and Ms Clopton-Edwards, whom he described as “two maiden aunts”. He was educated at Canford school, Dorset, before training for the theatre at the Italia Conti school in London, and made his acting debut in Where the Rainbow Ends at the New theatre in 1940.

After a busy period on stage, he had a couple of walk-on parts in the films Piccadilly Incident (1946) and The Root of All Evil (1947), before the director Herbert Wilcox cast him as Edward Courtney in the glamorous and highly successful The Courtneys of Curzon Street (also known as Katy’s Love Affair, 1947). Medwin was up and running in the heyday of postwar British cinema, notching up around 20 roles in five years.

They varied from the guileless Just William’s Luck (1948) and Woman Hater (1948) to Cavalcanti’s formidable For Them That Trespass (1949) and Thorold Dickinson’s The Queen of Spades (also 1949). Medwin played a spiv in Night Beat (1947), a cabby in Forbidden (1949), an elderly doctor in Anna Karenina (1948) and, alongside his fellow youngsters Roger Moore and Christopher Lee, was a marquis in Trottie True (also known as The Gay Lady, 1949).

Despite specialising in brash roles, he proved exceptionally versatile, and Michael Caine, who appeared with him in the war movie A Hill in Korea (1956), wrote: “I was amazed when I met him to discover that he had a very upper-crust accent. Cockney is a hard accent to do and he did it brilliantly.” By the time that film came out, Medwin was playing leading roles, but his attitude to work remained modest and he said later: “I’ve never been ambitious. Being a character actor in a high-risk business can be difficult, so it was a joy to be employed. I had no Everest to climb.”

The parts grew better, including one as the sparky British soldier in Four in a Jeep (1951), an intriguing portrait of the “four-way divide” in postwar Vienna. He was the title character in the spy story The Teckman Mystery (1954), and landed the best role of his career in The Intruder (1953), adapted by Robin Maugham from his novel Line on Ginger. Medwin was Ginger, a former soldier caught by his commanding officer (Jack Hawkins) while burgling the officer’s home. It was an intelligent snapshot of postwar Britain, with Medwin brilliant as the sympathetic, yet gutsy, unemployed “villain”, and a precursor to the social movies with which he and Finney would later be involved.

Until then, Medwin remained busy, acting in the thriller Bang, You’re Dead (AKA Game of Danger, 1954) and Joseph Losey’s bizarre short A Man on the Beach (1956), and giving valuable support to Max Bygraves in Charley Moon (1956), Frankie Vaughan in The Heart of a Man (1959) and Tommy Steele in The Duke Wore Jeans (1958). He was also on call for the Doctor and Carry On series and ubiquitous war films.

He had made his television debut as a boxer in Kid Flanagan (1948). In The Army Game (1957-58), he was Springer, the ringleader to four privates who regard national service as a licence for anarchy. In the series The Love of Mike (1960) he starred as the jazz musician Mike Lane, and in Shoestring (1979-80), he was the radio station boss Don Satchley to Trevor Eve’s phone-in detective Eddie Shoestring. He was in the Mel Smith comedy series Colin’s Sandwich (1988), the spy miniseries The Endless Game (1989), which starred Finney, and played the Red King in a TV version of Alice Through the Looking Glass (1998).

Later film roles included a theatre surgeon in Anderson’s Britannia Hospital (1982), a doctor in the Bond saga Never Say Never Again (1983), a producer in Hôtel du Paradis (1986) and a speechmaker in The Duchess (2008).

He had appeared in many theatre productions, including Man and Superman, Joe Orton’s What the Butler Saw and Noises Off. In 2010, playing Paris, he was the oldest cast member of a Bristol Old Vic production of Romeo and Juliet that starred the 76-year-old Siân Phillips as Juliet and Michael Byrne, in his late 60s, as Romeo. In 1988 he was a co-founder of David Pugh Ltd, a London and Broadway theatre production company and he remained a director well after announcing his retirement from acting in 2008.

He was appointed OBE in 2005 for services to drama.

His marriage to Sunny Sheila Back ended in divorce in 1971.

• Michael Hugh Medwin, actor and producer, born 18 July 1923; died 26 February 2020

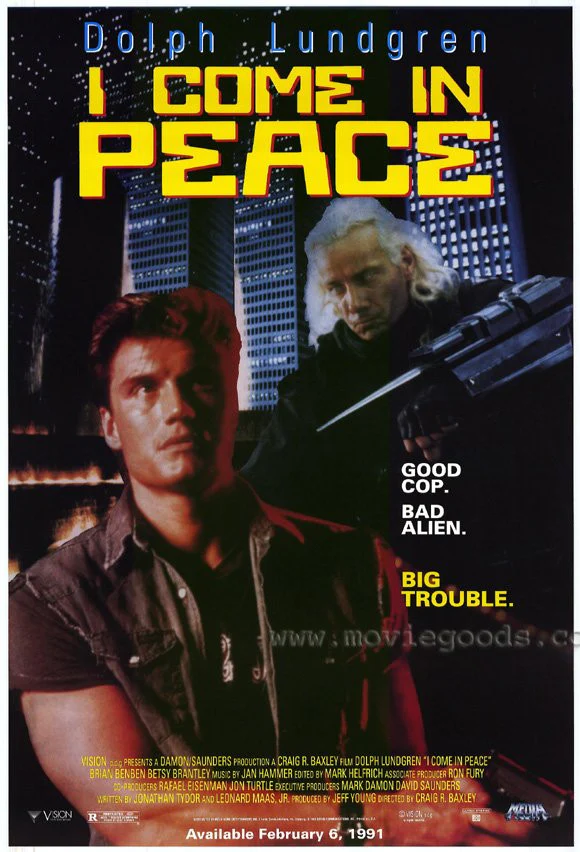

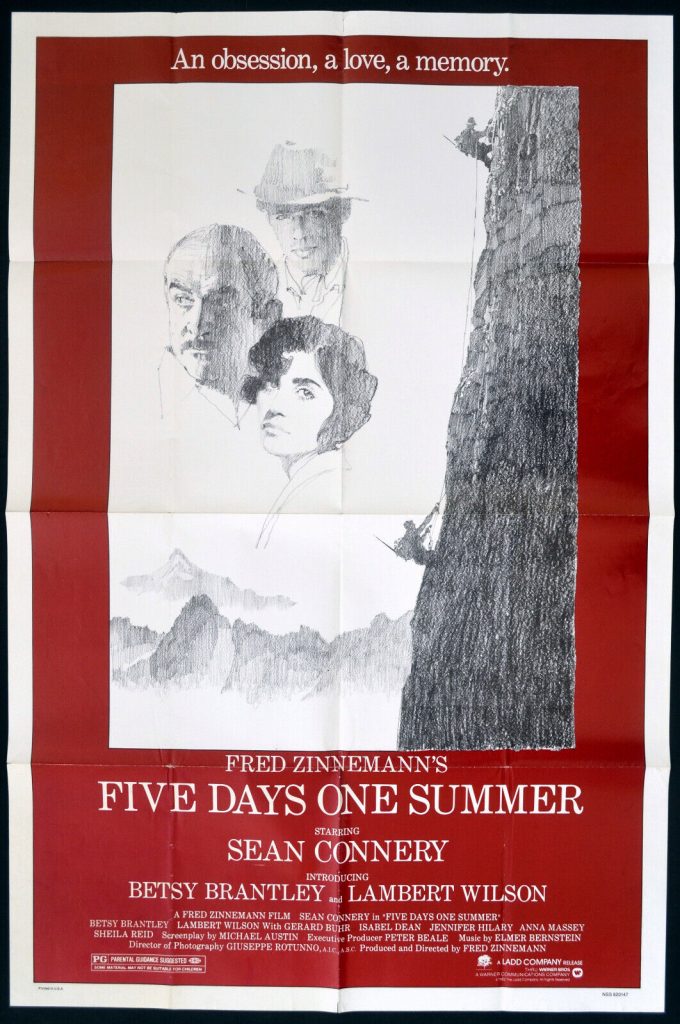

Betsy Brantley was born in 1955 in North Carolina. She studied acting in London and made her movie debut in a major role opposite Sean Connery in “Five Days, One Summer” directed by Fred Zinneman in 1982. The film was not a success though. Her other movies include “Another Country” and “The Princess Bride”.

IMDB entry:

Brian Croucher was born on January 23rd 1942. He started work as an apprentice printer and did a stint as a redcoat at Butlin’s holiday camp before applying to train as an actor at LAMDA. Throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s he appeared at London’s Royal Court Theatre in several plays by controversial writers and has also worked with the National Theatre as well as playing Fagin at the Marlowe Theatre,Canterbury,having had an early,uncredited role in the 1968 film version. On television he tested for the role of Blake in ‘Blake’s 7’, but ended up playing Travis instead and also appeared in children’s cult Sci-Fi serial ‘The Jensen Code’,though in the mid-1990s he was best known as Ted Hills in the soap ‘Eastenders’. He has appeared in most of the populist police TV series,his build and voice frequently getting him cast as a heavy,a role he plays in the 2012 film ‘Coolio’. Married to writer Christina Balit – whose plays he has directed for the stage – they have two children.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: don @ minifie-1

The above IMDB entry can also be accessed online here.

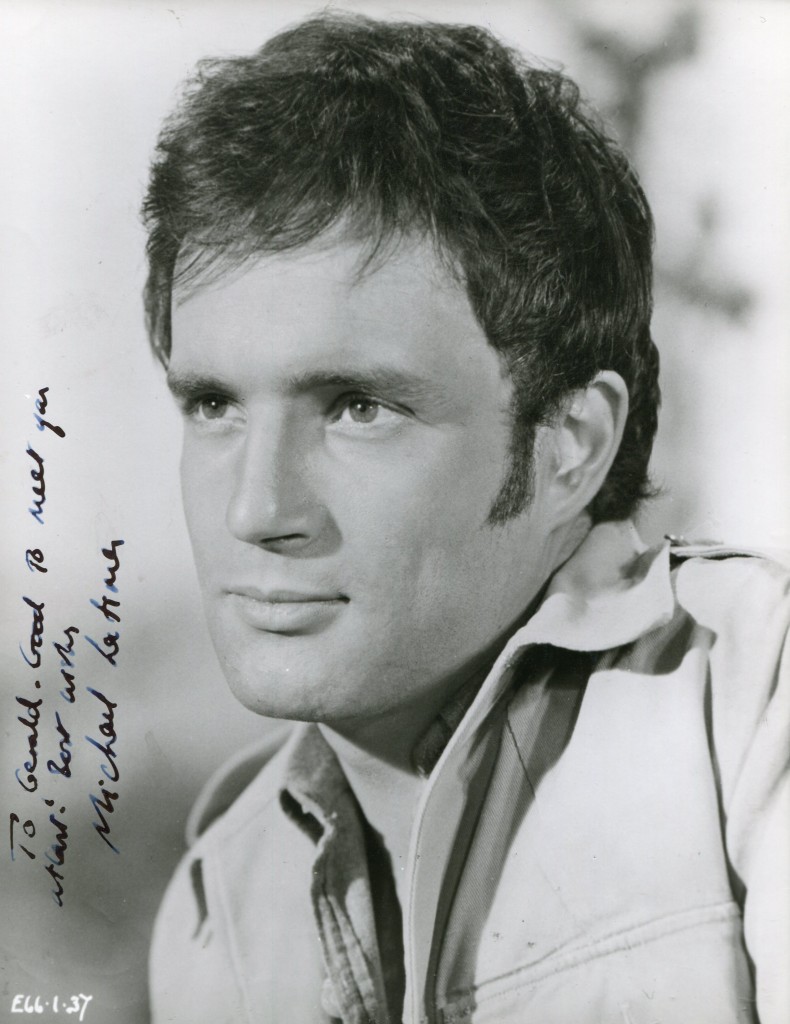

Basil Hoskins was born in 1929. He trained at RADA in London. He spent five seasons with the Shakespeare Memorial Company at Stratford. He played opposite Lauren Bacall in “Applause” in London’s West End in 1971. His movies include “Ice Cold In Alex” in 1958 and “North West Frontier” in 1959. He died in 2005.

His obituary from The Telegraph :

Basil Hoskins, who has died aged 75, was a character actor in the romantic mould and dedicated his career, which spanned nearly half a century, to the theatre.

Alternating between the classics and musical comedy, Hoskins had the height, looks, carriage and voice to range from suitors and flirts, deceived husbands and anxious lovers, to sardonic men of the world. Heartthrobs were an early speciality.

To earn a living he had, somewhat against his will, to work in television. In Emergency Ward 10, Hoskins was the flirtatious Dr Lane-Russell; and, when he wanted to return to the theatre, it proved difficult to write him out.

Lane-Russell had already been up before the General Medical Council, so the scriptwriters had him propose to a staff nurse who turned him down, driving him to find work in a public health department.

Hoskins did, though, still appear in television dramas, among them The Prisoner, Clayhanger, New Avengers, The Return of Sherlock Holmes, The Blackheath Poisonings and Cold Comfort Farm. His film credits included Ice Cold in Alex, The Millionairess, North-West Frontier, Lost in London and Heidi.

Basil William Hoskins was born on June 10 1929, and trained at Rada. A devotee of Shakespeare from the beginning, he joined the old Nottingham Playhouse company as Duncan for the revival of John Harrison’s production of Macbeth in 1951; after a stint in Victorian music hall he moved to Robert Atkins’s Open Air Theatre in Regent’s Park.

According to The Daily Telegraph, as Orlando to Mary Kerridge’s Rosalind Hoskins covered “the vast distances of the grassy stage with a good stride” and put on a wrestling match “in which necks seemed likely to be broken at any moment”.

Hoskins then spent five seasons with the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre Company at Stratford-on-Avon. He appeared as Bassanio in The Merchant of Venice; Demetrius in A Midsummer Night’s Dream; Fortinbras in Hamlet; Ferdinand to Geraldine McEwan’s Princess in Peter Hall’s first Stratford production, Love’s Labour’s Lost; and as Lucius to Laurence Olivier’s Titus Andronicus (with Vivien Leigh and directed by Peter Brook).

Touring Australia with the Old Vic in the 1950s, Hoskins played Bassanio opposite Katharine Hepburn’s Portia in The Merchant of Venice.

Hoskins’s first West End lead came opposite Vivien Leigh in Jean Louis-Barrault’s production of Jean Giraudoux’s last play, Duel of Angels (Apollo, 1958). Opposite Alec Guinness in Terence Rattigan’s Ross (Haymarket, 1960), Hoskins appeared as a Turkish Captain; and three years later he enjoyed himself as Worthy, a lady-killer, in Virtue in Danger (Mermaid), Paul Dehn’s musical version of Vanbrugh’s Restoration comedy, The Relapse.

With Robert Tannitch’s Highly Confidential (Cambridge, 1969), Hoskins launched the first of a series of manly admirers of star actresses; three years later he had a similar part in the American musical Applause (Her Majesty’s) opposite Lauren Bacall.

After touring in Stephen Sondheim’s Little Night Music, Hoskins found himself again singing an actress’s praises – this time Noele Gordon’s – in Irving Berlin’s Call Me Madam (Victoria Palace, 1983). He continued to appear in musicals in London into the 1990s, and also did much fine work out of London.

Basil Hoskins never married; for many years he was the companion of the late Harry Andrews.

The Telegraph original obituary can be accessed here.

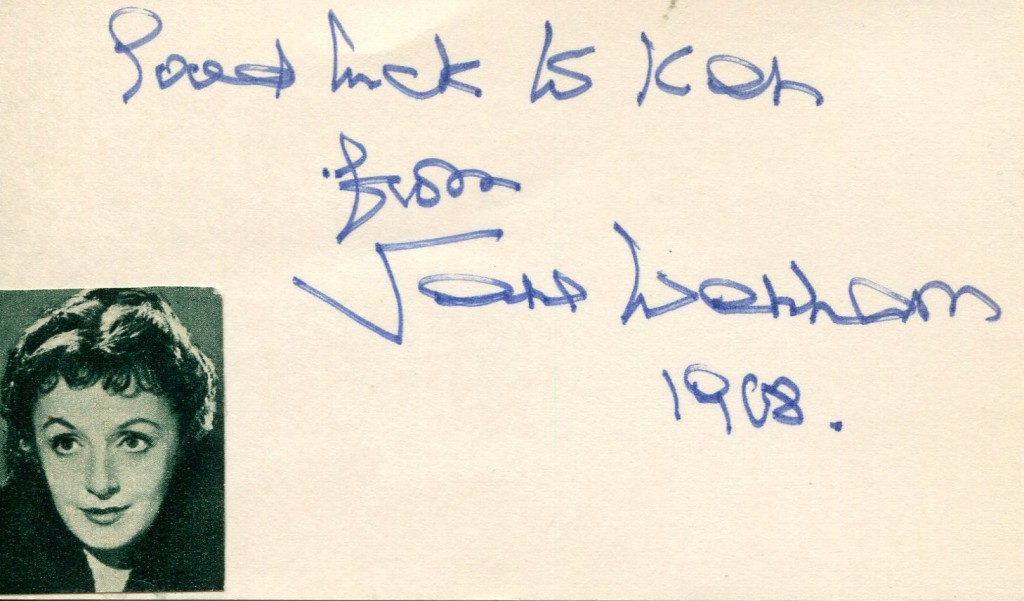

Jane Wenham was born in 1927 in Southampton. She made her film debut in “An Inspector Calls” in 1954. Her other films include “The Teckman Mystery” and “Make Me An Offer”. She has a son Simon from her marriage to Albert Finney. Ms Wenham died in 2018.

The actor Jane Wenham, who has died aged 90, brought a delightful stage presence to work that ranged from Shakespeare to the musical Salad Days and even to pantomime. In fact, Wenham seemed ready for anything.

At the Bristol Old Vic in 1947, her Desdemona in Othello was compared to Peggy Ashcroft’s opposite Paul Robeson 17 years earlier by the critic of the London Evening Standard. When first Wenham opened her mouth to sing, in Julian Slade’s Old Vic version of The Duenna in 1952, in which she later appeared at the Westminster theatre, her soprano voice was rated “the great success of the evening”.

She served her time as Jane, the jolly university undergraduate in Slade’s long-running hit Salad Days; and went on to gather plaudits in such West End shows as Wild Thyme (St Martin’s, 1955), a musical version of Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors (Arts, 1956), Grab Me a Gondola (Lyric, 1956) and Virtue in Danger (Mermaid and Strand, 1963).

Jane Wenham leaning out of a train carriage as she and the rest of the Old Vic theatre company prepared to tour South Africa in 1952. Photograph: Central Press/Getty Images

The daughter of Dorothy (nee Wenham) and Arthur Figgins, she was born in Southampton and adopted her mother’s maiden name for the theatre. She trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama in London before making her West End debut in 1945 in the great Old Vic revival of Henry IV Part I at the New theatre, with Ralph Richardson as Falstaff. That year she also appeared in a film of the 1943 stage success Pink String and Sealing Wax.Advertisementhttps://4409f2364d31f3e4b6c3748210922e0e.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-37/html/container.html

After visiting New York with the Old Vic company, she returned to London as Gladys in Thornton Wilder’s history of the world in comic strip, The Skin of Our Teeth (1946), but realised that rep training was more important than the West End, so she joined the Bristol Old Vic. Within a few weeks she was praised for the finest Desdemona (to William Devlin’s Othello) for 17 years; and as Ophelia to Robert Eddison’s Hamlet, she transferred to the St James’s theatre in London in 1948.

In two seasons at Bristol, her singing voice caught attention as Aladdin, as Sherah in James Bridie’s Tobias and the Angel and as Cinderella, suggesting “the wistfulness and helplessness of the character”. In Sheridan’s The Rivals, her “piquant and tiny” Lucy won further praise; and after a Vera in Turgenev’s A Month in the Country – “a touching picture of young girlhood shattered in the very act of emerging into womanhood” – in Romeo and Juliet she showed a “wistful, affecting quality which accentuated Juliet’s child-like vulnerability”. As the Times put it: “Even the potion scene she nearly brings off by playing much of it down, as if its terrors were almost too great for her to put into words.”

Wenham in 1949 rejoined the Old Vic at the New theatre in London. Her successes continued in 1950 as a dirty and décolleté Pimple, one of Hogarth’s gin addicts, in She Stoops to Conquer; as a lively, cherry-lipped and bedazzled Katya in A Month in the Country; and as Marianne in Molière’s The Miser. When the company returned to the bomb-damaged Old Vic, she offered a small, fiery and compact Hermia in A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1951; and in 1953 made “a wise and merry” Nerissa in The Merchant of Venice.

Following a detour to the lyric stage with The Duenna, Wild Thyme and Grab Me a Gondola, it was back to straight Shakespeare. During the 1957 season at Stratford-upon-Avon, she was Celia in As You Like It, Calphurnia in Julius Caesar and Iris in The Tempest. That year she married Albert Finney in Birmingham, where he was appearing in Henry V.

After a stint as Mrs Elvsted to Joan Greenwood’s Hedda Gabler (Arts and St Martin’s, 1964), Wenham returned to Bristol in 1968 for two major roles – as Sister Jeanne in a revival of John Whiting’s The Devils and then as Maggie in Iris Murdoch’s The Italian Girl, which transferred to the West End (at Wyndham’s).

Then she settled down for a long spell with the National Theatre, leaving in 1972 for the Young Vic to play Jocasta in Oedipus, but returning in 1974 to take over (from Jeanne Watts) as Dora Strang in Peter Shaffer’s Equus, at the Old Vic, continuing at the Albery until 1977.

She was unable to resist two even fatter parts at the Northcott theatre, Exeter, in 1978 – the title role in Hugh Whitemore’s Stevie, and Catherine of Braganza in Shaw’s Good King Charles’s Golden Days. Wenham returned to the West End (the Queen’s) as Her Ladyship in Ronald Harwood’s The Dresser in 1980.

Her feature films included An Inspector Calls (1954) and Make Me an Offer (1955), but Wenham was better known for her television roles. She appeared in favourites such as Porridge, Bergerac, Last of the Summer Wine, The Darling Buds of May and Inspector Morse, was Mrs Brittain in the 1979 miniseries Testament of Youth and had a small role in the first series of Downton Abbey (2010), as Mrs Bates, mother of Lord Grantham’s valet.

Wenham is survived by a son, Simon, from her marriage to Finney, which ended in divorce in 1961.

• Jane Wenham, actor and singer, born 26 November 1927; died 15 November 2018

• Eric Shorter died in January this year

Alan Badel was born in 1923 in Manchester. He first came to attention for his performance as ‘Romeo’ opposite Claire Bloom in “Romeo and Juliet” at the Old Vic in 1950. He had a major stage career and also gave terrific performances on television in “Bill Brand” and “The Woman in White”. Surprisingly he did not become a major movie star despite getting a lead role in Hollywood in 1953 opposite Rita Hayworth in “Salome”. His other films include “Magic Fire” and “This Sporting Life”. He died at the age of 58. His daughter is the actress Sarah Badel.

“Wikipedia” entry:

He was an English stage actor who also appeared frequently in the cinema, radio and television and was noted for his richly textured voice which was once described as “the sound of tears”.

Badel was born in Rusholme, Manchester and educated at Burnage High School. He fought with the French Resistance during theSecond World War.

In his early career, he played leading parts, including Romeo and Hamlet, with the Old Vic and Stratford companies

Badel’s most notable early screen role was as John the Baptist in the Rita Hayworth version of Salome (1953), a version in which the story was altered to make Salome a Christian convert who dances for Herod in order to save John rather than have him condemned to death.

Badel portrayed Richard Wagner in Magic Fire (1955), a biopic about the composer, and Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg in theParamount film Nijinsky (1980).

He also played the role of Karl Denny, the impresario, in the film Bitter Harvest (1963) based on the novel 20,000 Streets Under the Sky by the author and playwright Patrick Hamilton. In the film he engages a young Welsh girl called Jennie Jones who, under his control, becomes a high class prostitute who commits suicide. The film starred Janet Munro in the lead part of Jennie Jones.

The film also starred a number of character actors who went on the make numerous film and television roles, namely, John Stride, William Lucas, Norman Bird, Allan Cuthbertson, Anne Cunningham and Francis Matthews. The landlady of John Stride’s character, Joe, was played by Thora Hird who received no opening or closing credit in the film.

Also in 1963 he played opposite Vivien Merchant in the TV production of Harold Pinter‘s play The Lover.

He also played the French Interior Minister in The Day of the Jackal (1973), a political thriller about the attempted assassination of President Charles de Gaulle. Badel also played the villainous sunglasses-wearing Najim Beshraavi in Arabesque (1966) with Gregory Peck and Sophia Loren. One of Badel’s most noted roles was that of Edmond Dantès in the 1964 BBC television adaptation of The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas, which also starred Michael Gough. He appeared in television adaptations of The Moonstoneand The Woman in White by Wilkie Collins.[citation needed]

Badel married the actress Yvonne Owen in 1942 and they remained married until his sudden death in Chichester, aged 58. Their daughter Sarah Badel is an actress

Mervyn Johns was born in Pembroke, Wales in 1899. His film debut was in “Lady in Danger” in 1944. He was a busy character actor in British films including “Convoy”, “Pink String and Ceiling Wax”, “A Christmas Carol” and “The Sundowners”. He died in 1992. His daughter is the actress Glynis Johns.

Adam Benedick’s “Independent” obituary:

Mervyn Johns was one of the soundest and most sincere of character actors. His gallery of mostly mild-mannered, lugubrious, amusing, sometimes moving ‘little men’ stretched back through scores of films and plays and television series – victims usually, quiet always, and never less than authentic: petty crooks, modest bank clerks, henpecked husbands, diffident clerics – almost all Welsh and as obliging and as true as can be.

This was Johns’s great and sometimes touching quality. He seemed never to be acting. He was himself short of build, but the secret of his acting was not so much a matter of height as of depth – of being able to get under the skin of a character. He could also muster, when required, an other-worldly air of almost celestial feyness, or dreamy intuition. But his acting did not always fall into such gentle categories.

Half a century ago it was quite different. If few remember him in 1936 at The Embassy, Swiss Cottage (now the Central School), as Sir John Brute in the Restoration comedy The Provok’d Wife, he provoked the best judge of acting of the day – James Agate – to hail him as ‘blazingly good’. Trying not to declare that this new young actor whom the critic was seeing for the first time was another David Garrick, Agate had nothing but superlatives – ‘a magnificent performance which would have warmed the heart’s cockles of the old playgoers . . . In this actor’s hands, Sir John is a brute indeed, not a pewling mooncalf, but a roaring bull. Mr Johns lets us see the pleasure he is taking in the fellow’s brutish gusto. There are actors who could make the man as unbearable to an audience as he was to his own circle. Mr Johns, by lifting a corner of the brute’s mind to show us his own, is right with Garrick.’

Johns had been on the stage for 13 years before that production, soundly trained for eight of them in rep at Bristol after an eventful youth, first as a medical student, then with the Royal Flying Corps in the First World War (‘I don’t think there was a single second when I was not scared to death’) and finally RADA, where he gained a gold medal.

He had a natural gift for playing frightened men, but before typecasting overtook him – so that it became hard to imagine what Agate meant with that comparison with Garrick, especially the talk about gusto – Johns not only showed a relish for Restoration comedy, but was also rated a ‘quintessential’ Priestley and Shavian actor in such shows as Time and the Conways (1937), The Doctor’s Dilemma (1939), Heartbreak House (1943), in which he replaced Robert Donat as Captain Shotover, and as Dolittle in Pygmalion (1947); though even before the Second World War he provoked another critic to dub his performance a masterpiece as a ‘brave little miner, irascible but warm’ in Jack Jones’s violent and very Welsh play Rhondda Roundabout.

And indeed Johns brought a masterly touch to scores of other roles, especially, for example, his architect whose dreaded dreams came true in Dead of Night (1945), opposite Michael Redgrave, whom he had followed in that strange play, The Duke of Darkness, a few years earlier; or as Lester in the melodrama Tobacco Road (1949), or the infinitely pious parent in Gwyn Thomas’s fountain of Welshness The Keep (Royal Court, 1961). He was unforgettable as a slow-dying sailor in the film San Demetrio, London.

But what if the Second World War had not turned the London theatre topsy-turvy? Might we not have seen more of the roaring bull and the brutish gusto? Might he have escaped typecasting?

His daughter Glynis Johns was already a star when his own stardom – if one dares to call it that for an actor who played so many supporting roles in the last half of his career – was on the wane; but he rarely gave a bad performance, however bad his material, which is more than can be said of many stars.

His Friar Laurence, for example, in Renato Castellani’s supposedly all-star Anglo-Italian Romeo and Juliet (1954) was just about the best thing in it; and television viewers will always be grateful for his work in Kilvert’s Diary and The New Avengers.

Nor should one forget that amid the modesty of his demeanour and reticence of temperament, his talent for looking so eloquently and so silently into outer space. This gaze was singularly penetrative, eerie and sometimes haunting; it needed no script, and could both chill and cheer. It was one of the most cheering aspects of his later life that in 1976, while in retirement at Denville Hall, at Northwood, in Middlesex, he married the widowed actress Diana Churchill, also in retirement.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.

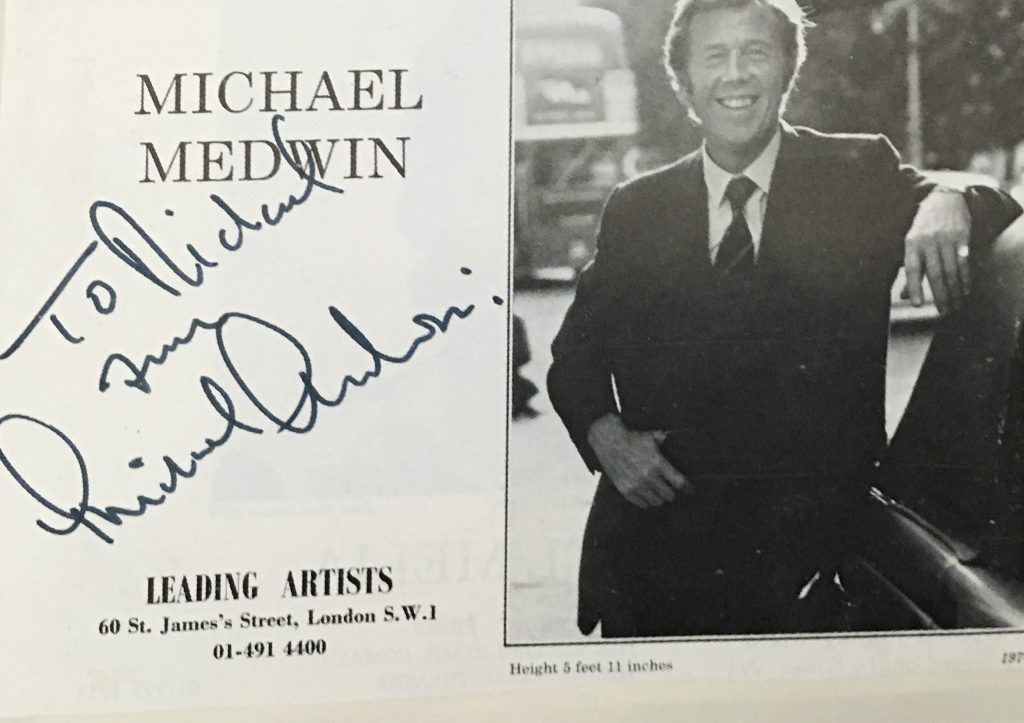

Anyone who knows me are aware that I am a bit of a movie buff. Over the past few years I have been collecting signed photographs of my favourite actors. Since I like movies so much there are many actors whose work I like.