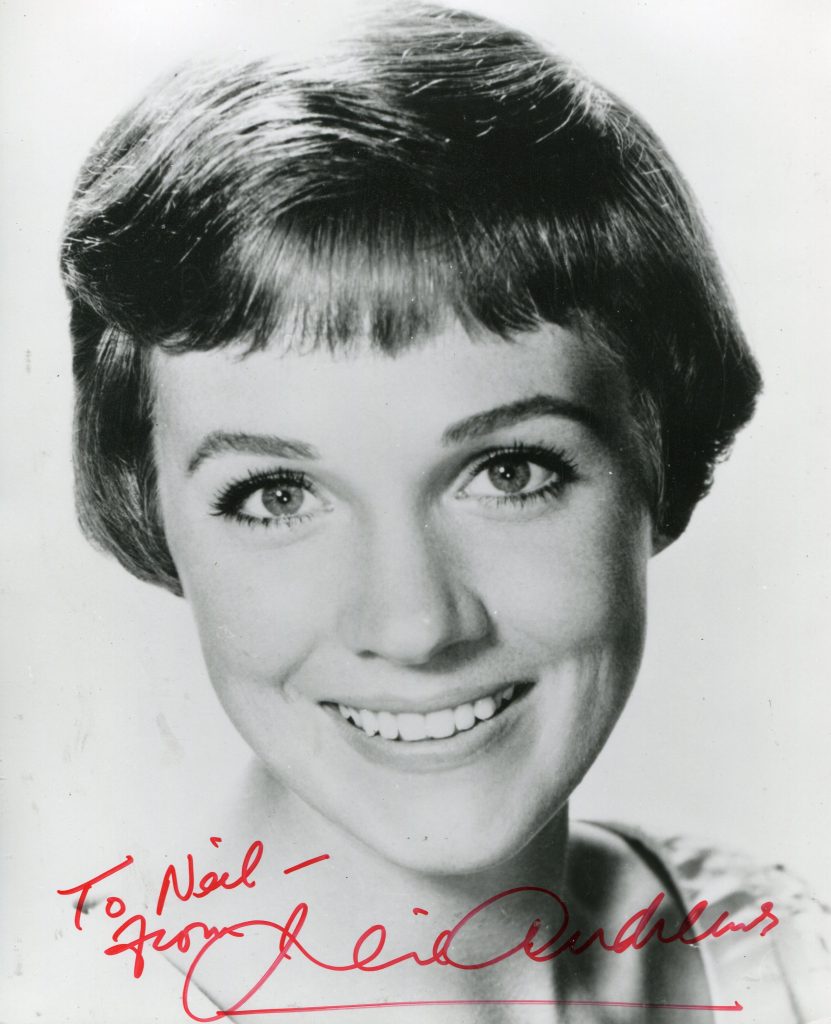

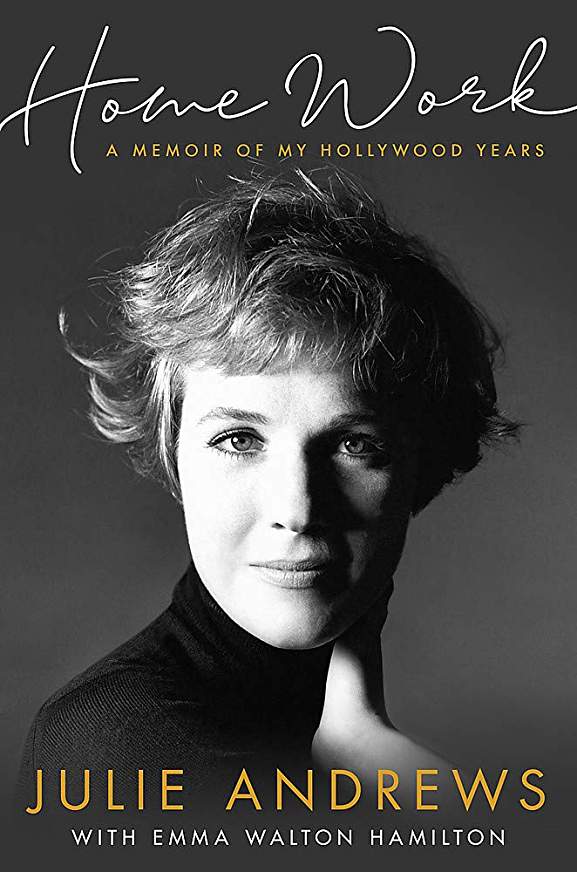

“When Julie Andres cam along there was only a handful of female stars with any appeal at all. Most of the others were the same tired hopefuls, manufactured if not by the studios, by their own PR firms. With Julie, the genuine thing was back and everyone knew it. She embodied some of the best qualities of the great stars of the 30s, on the surface the same common sense, underneath the hint of other things – the gaiety of Irene Dunne, the independence of Hepburn, the irreverence of Carole Lombard, the vulnerability of Margaret Sullavan. And what they had and she has is style and discipline. She knows instinctively what to do, what she can do. She is what she seems to be” by David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars- The International Years. (1972)

Singer-actress Julie Andrews came from humble beginnings on the English vaudeville circuit before going on to become one of the showbiz’s brightest talents, and ultimately, one of entertainment’s greatest living treasures. After a string of hit productions on Broadway – and being denied the opportunity to reprise her roles on film – Hollywood at last opened its doors to Andrews when she landed the lead in Walt Disney’s “Mary Poppins” (1964). Her enchanting performance, combined with a stunning four-octave vocal range, won her an Oscar. Andrews followed with her career-making turn as the embodiment of kindness and sincerity, Maria Von Trapp, in “The Sound of Music” (1965). The record breaking film would remain one of the most successful and beloved movies of all time, gaining legions of fans for generations to come. As the Sixties came to a close, Andrews’ professional output waned, although her personal life flourished with a marriage to director Blake Edwards. Andrews went on to score more cinematic hits with her director husband including “10” (1979) and “Victor/Victoria” (1982), as well as enjoy a respectable career as a children’s book author. In a tragic bit of irony, the angelic-voiced actress would lose her instrument after a botched throat operation in 1998. However, this did not prevent Andrews from winning over new audiences with turns in projects like “The Princess Diaries” (2001), or lending her still regal voice to the animated fairy tale romp, “Shrek 2” (2004). Through the years, Andrews came to epitomize the concepts of dignity, grace and rare talent – traits that endeared her to fans the world over for nearly 50 years.

Born on Oct. 1, 1935 in Walton-on-Thames, England, Andrews joined her mother Barbara and stepfather Ted Andrews’ touring vaudeville act at the age of 12. In her first major appearance – in “Starlight Waltz” (1947) – Andrews brought the house down at the Hippodrome with her amazing vocal prowess. She quickly graduated to top billing, becoming the family’s primary breadwinner on the strength of her several octave-range soprano and continued to tour once her parents retired, traveling with a tutor until she was 15. Title roles in pantomime productions of “Humpty Dumpty” (1948), “Red Riding Hood” (1950) and “Cinderella” (1953) preceded her Broadway debut as Polly in Sandy Wilson’s 1920s pastiche, “The Boyfriend” (1954). Two years later, she was starring on the Great White Way as Eliza Doolittle in a production of “Pygmalion,” and in Lerner and Loewe’s “My Fair Lady,” which earned her a Tony nomination. After a four-year run, Andrews landed another plum role, playing Guinevere to Richard Burton’s King Arthur in Lerner and Loewe’s “Camelot.” A second Tony nomination soon followed.

Though her lilting, sweet soprano and prim British charm had earned her kudos as a Broadway musical star, Andrews was slow to win Hollywood over and would lose all three roles she had created on Broadway to non-singers in their film incarnations. She did impress Walt Disney enough, however, to be offered the title role of “Mary Poppins” (1964), although she kept him waiting until it was definite that Eliza Doolittle would be played by Audrey Hepburn. A truly wonderful amalgam of live-action, animation and Oscar-winning music, “Mary Poppins” earned her an Academy Award for Best Actress. That same year, she displayed her non-musical abilities opposite James Garner in “The Americanization of Emily” before reaching greater heights as Maria in the blockbuster film version of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “The Sound of Music” (1965), which became the highest-grossing movie of all time until “Jaws” knocked it from its perch a decade later. The incredible success of that film chiseled her wholesomeness in granite, while the musical “Thoroughly Modern Millie” (1967) reinforced her as a sweet thing with terminal cuteness. Hoping to repeat the success of their initial teaming on “The Sound of Music,” director Robert Wise cast Andrews as stage legend Gertrude Lawrence in “Star!” (1968), but the actress failed to come across in that razzle-dazzle biopic-cum-musical. Nevertheless, Andrews acquitted herself in the production numbers, but was hampered by the script’s take on Lawrence.

Attempts to break away from her goody-two-shoes stereotyping by appearing in less wholesome, non-musical fare – e.g., Hitchcock’s “Torn Curtain” (1966) – were ineffectual, and it would take frequent collaborations with second husband Blake Edwards – including roles in “The Tamarind Seed” (1974), “10” (1979) and “That’s Life” (1986) – for her to finally prove herself a deft comedienne and a warm dramatic actress. In his glib Movieland satire “S.O.B” (1981), Andrews played an actress baring her breasts for financial reasons, and since she was still trying to shed her virginal image at the time, her going buff made the film a parody of itself. One of her most significant big screen successes was Edwards’ gender-bending, often hilarious “Victor/Victoria” (1982), which earned her a third Best Actress Oscar nomination. Over a decade later, she reprised its woman playing a man playing a woman for the Broadway version. Andrews created a flap when she declined her Tony nomination in protest because no one else associated with the production received a nod. A televised version of the 1995 production was aired as part of the Bravo cable series “Broadway on Bravo.”

In 1998, Andrews underwent throat surgery that went horribly awry and subsequently robbed her of her crystalline, perfectly pitched singing voice. In 2000, her malpractice suit against the doctors who allegedly botched her surgery was settled for an undisclosed sum, estimated at $30 million. After some counseling to help her deal with the trauma of the loss of her most treasured asset, Andrews also engaged in therapy that helped her regain some of her vocal range. In the meantime, she stayed busy as an actress, appearing as the awkward fledgling royal Anne Hathaway’s oh-so-regal grandmother in Garry Marshall’s surprise hit film, “The Princess Diaries” (2001), a role she reprised for the sequel “The Princess Diaries 2: Royal Engagement” (2004). She also provided the voice of Queen Lillian, mother of Princess Fiona (Cameron Diaz) in the animated sequels, “Shrek 2” (2004) and “Shrek the Third” (2007). That same year, Andrews provided narration for Disney’s spot-on self-parody of the fairy tale genre it helped create with “Enchanted” (2007), one the studio’s most successful live action features in years. Less worthy of the famous Andrews charm was the Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson vehicle “Tooth Fairy” (2010), in which she played the head tooth fairy, Lily. She again voiced the Queen in “Shrek Forever After” (2010), in addition to voicing the mother of super villain extraordinaire, Gru, in Dreamworks’ animated feature, “Despicable Me” (2010).

As if the multi-faceted entertainer did not have enough feathers in her cap, Andrews authored several children’s books – something she had actually been doing for years – including The Very Fairy Princess written with her daughter, Emma Walton Hamilton. The mother-daughter team collaborated once again on a personally-selected anthology, Julie Andrews’ Collection of Poems, Songs, and Lullabies. The illustrated book was accompanied by four CDs featuring Andrews introducing the selections, and giving dramatic readings of the material along with Hamilton. In November 2010, Andrews’ most revered film made headlines once more, when its core cast reunited for the 45th anniversary of “The Sound of Music” on the “Oprah Winfrey Show.” The studio audience was ecstatic, as cast members like Christopher Plummer regaled them with anecdotes from the production. Sadly, the year would end on a supremely tragic note, when on December 15, Andrews’ husband, collaborator and friend, Blake Edwards, died of complications due to pneumonia. The actress and their five children were at Edwards’ hospital bedside when he passed.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online

here.