TCM overview:

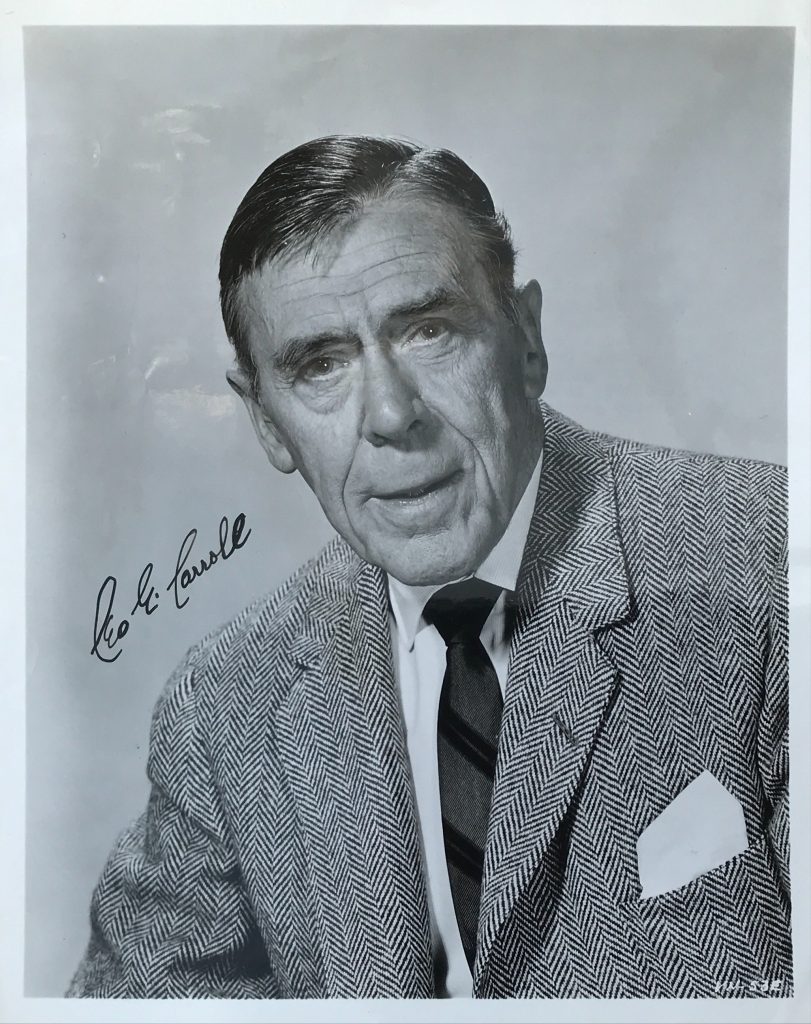

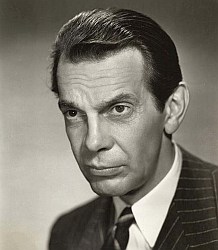

Exceptionally tall, with distinctive, unconventional features and a commanding presence, actor Raymond Massey built an impressive career out of playing reassuring authority figures and scheming villains equally well. The Canadian-born actor first honed his craft on the stages of the U.K. for nearly 10 years before venturing across the Atlantic to appear on Broadway as “Hamlet” and in early sound pictures like “The Speckled Band” (1931), in the role of Sherlock Holmes. Massey demonstrated his versatility with venomous characters in films like “The Prisoner of Zenda” (1937) juxtaposed against his career-defining portrayal of the 16th U.S. president in “Abe Lincoln in Illinois” (1940), based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning play written with him in mind. Massey became the stuff of Hollywood legend when the aftermath of his divorce from actress Adrianne Allen inspired the beloved Tracy-Hepburn comedy “Adam’s Rib” (1949). As an actor, Massey continually impressed with is ability to make difficult characters sympathetic in such films as “The Fountainhead” (1949), opposite Gary Cooper, and as James Dean’s emotionally unavailable father in “East of Eden” (1955). A younger generation of fans came to appreciate his later work as Richard Chamberlain’s authoritative mentor Dr. Gillespie on “Dr. Kildare” (NBC, 1961-66). Even as his half-century career neared its end, Massey continued to make memorable contributions to such big-budget Hollywood offerings as the Western “Mackenna’s Gold” (1969). One of the first and best examples of a “working actor” in film, Massey never failed to elevate the integrity of any project.

Raymond Hart Massey was born in Toronto, Ontario, Canada on Aug. 30, 1896. He was the son of Ann and Chester Daniel Massey, whose family roots could be traced back to pre-Revolutionary War America. Although Raymond participated in a few school productions while attending the Appleby School in Oakville, Ontario, the assumption was that he would eventually enter into his well-to-do family’s farm equipment business upon completing his education. As a member of the Canadian Officer’s Training Corps while attending the University of Toronto when World War I began, he was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Canadian Army. Massey served with a field artillery unit at France’s Western Front until he was wounded at Ypres in 1916. Hospitalized for several months and diagnosed with shell shock, he was later sent to the U.S., where he served as an artillery instructor for a time before rejoining the Canadian Expeditionary Forces in 1918 and being sent to Siberia in the wake of the Russian Communist Revolution. While stationed at Vladivostok, Massey was put in charge of entertainment for the troops, for whom he mounted several theatrical productions. In later years, the venerable actor related that it was then that the performing bug truly bit him, once and for all.

Upon being discharged, Massey attended Britain’s Balliol College, Oxford. The stay at Oxford was not a long one, however, and before long he was back home in Canada, where he attempted to make a go of it in the family business. But the thrill of the theater still called to Massey, who, upon the advice of renowned thespian John Drew and after pleading for permission from his patriarchal Methodist father, returned to England to pursue a career on the stage. Eventually the determined actor landed his first professional role in a 1922 production of Eugene O’Neill’s “In the Zone” and from that point forward, there was no looking back. Within four years, Massey was established on the stages of London as both an actor and director, and in less than a decade, he made trip back across the Atlantic for his Broadway debut as the star of a revival of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” in 1931.

Although he had made a pair of brief, uncredited screen appearances two years prior, Massey’s first major film role was as Sherlock Holmes in the mystery “The Speckled Band” (1931), the first talkie to depict the exploits of the great detective. Other leading roles soon came in films like director James Whale’s superb “The Old Dark House” (1932), opposite Boris Karloff. Massey’s imposing features also allowed him to adapt easily to more villainous roles, such as the slithering Chauvelin in “The Scarlet Pimpernel” (1935). Massey had far from abandoned work on the stage, though, appearing on Broadway many times over the next two decades and earning accolades for such portrayals as “Ethan Frome” in 1936. Back on screen, he showed his bad side twice more as Black Michael opposite David Niven’s “The Prisoner of Zenda” (1937) and as the conniving Prince Ghul in the British Empire epic, “The Drum” (1938). At 6’3″ tall, Massey was perfectly suited to play the legendarily lanky commander-in-chief in the Pulitzer Prize-winning Broadway play “Abe Lincoln in Illinois” (1938) which was written specifically with the actor in mind by playwright Robert Sherwood.

Massey’s personal life took a decidedly truth-is-stranger-than-fiction turn in 1939 when he and his wife of 10 years, actress Adrianne Allen, entered into divorce proceedings. Massey and Allen were each represented by one-half of the husband and wife legal team of William and Dorothy Whitney. With the divorce finalized, the attorneys quickly divorced each other and went on to marry their respective famous clients – Massey and Allen. The bizarre turn of events later inspired husband and wife screenwriting team of Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin to pen the classic 1949 battle of the sexes comedy “Adam’s Rib,” starring Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn. During their time as a couple, Massey and Allen had two children, Daniel and Anna, both of whom went on to enjoy acting careers of their own.

The following year, Massey reprised his most famous stage persona in the film version of “Abe Lincoln in Illinois” (1940), for which he received an Academy Award nomination. He took on another historical figure that year with a wild-eyed, unsympathetic portrayal of the radical abolitionist John Brown in “Santa Fe Trail” (1940), starring Errol Flynn as Confederate Civil War hero J.E.B. Stuart. Working steadily throughout the war years, Massey took over the role his “Old Dark House” co-star Boris Karloff had originated on stage for director Frank Capra’s film adaptation of the play “Arsenic and Old Lace” (1944), then lent his intimidating visage to the role of a stern prosecutor in the Heaven-set sequences of the imaginative Michael Powell-Emeric Pressburger fantasy, “A Matter of Life and Death” (1945). Maintaining his ties to the stage, the actor returned to Broadway to play Professor Henry Higgins in the 1945 production of “Pygmalion.”

Other notable work of the period included a performance as General Ezra Mannon – an updated version of Greek King Agamemnon – in “Mourning Becomes Electra” (1947), the screen adaptation of O’Neill’s epic reinterpretation of “The Oresteia,” a trilogy of Greek tragedies by Aeschylus. He was sympathetic as the well-meaning but weak-willed newspaper magnate Gail Wynand in director King Vidor’s adaptation of author Ayn Rand’s treatise on individuality, “The Fountainhead” (1949), starring Gary Cooper as visionary architect Howard Roark. Still at the height of his powers, Massey was excellent years later as the proud and emotionally distant patriarch Adam Trask opposite James Dean in the filmed version of Steinbeck’s “East of Eden” (1955) and delivered a far more balanced portrayal in his second outing as John Brown in the under-appreciated “Seven Angry Men” (1955).

By the second half of the decade, Massey transitioned more predominantly into the burgeoning medium of television, appearing in guest spots on many of the popular anthology series of the day, such as “General Electric Theater” (CBS, 1953-1962). The venerable stage and film star became widely known by a new generation of audience as the gruff but caring Dr. Gillespie on the popular medical-drama “Dr. Kildare” (NBC, 1961-66), featuring a fresh-faced Richard Chamberlain in the title role. Fans of his work as the stern taskmaster Gillespie may not have been surprised when Massey made his personal politics known by actively campaigning for Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater during the 1964 race against incumbent Lyndon B. Johnson.

Long established as an elder statesman of screens both large and small, Massey continued to appear in projects, albeit with less frequency as the ’60s drew to a close. His final performance in a feature film was as a fortune-hunting preacher in the Gregory Peck Western “Mackenna’s Gold” (1969). This was followed a few years later by his last television appearances in the political-thriller “The President’s Plane is Missing” (ABC, 1973) and the family film “My Darling Daughter’s Anniversary” (ABC, 1973), starring one of his contemporaries, Robert Young. After battling a case of pneumonia for nearly a month, Massey died at Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles on July 29, 1983, just weeks shy of his 87th birthday. Somewhat overshadowing the sad event was the passing of actor David Niven, Massey’s “Prisoner of Zenda” co-star, who died that same day.

By Bryce Coleman

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

.jpg)