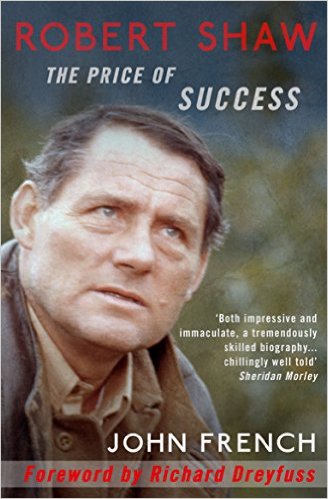

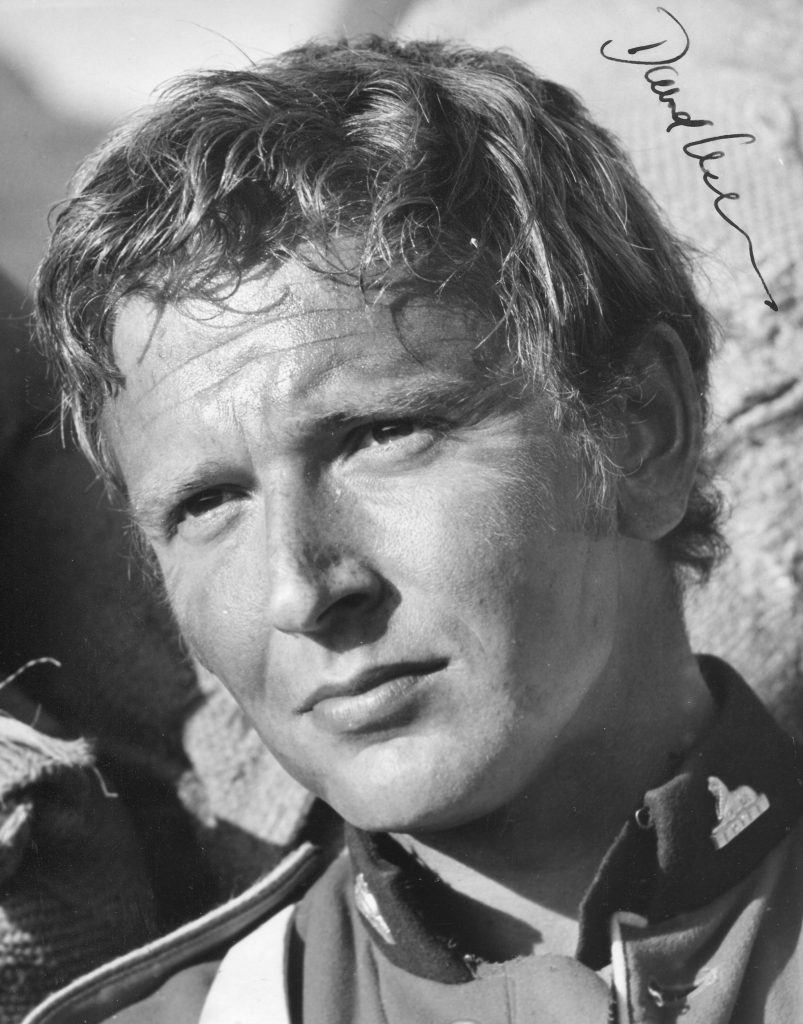

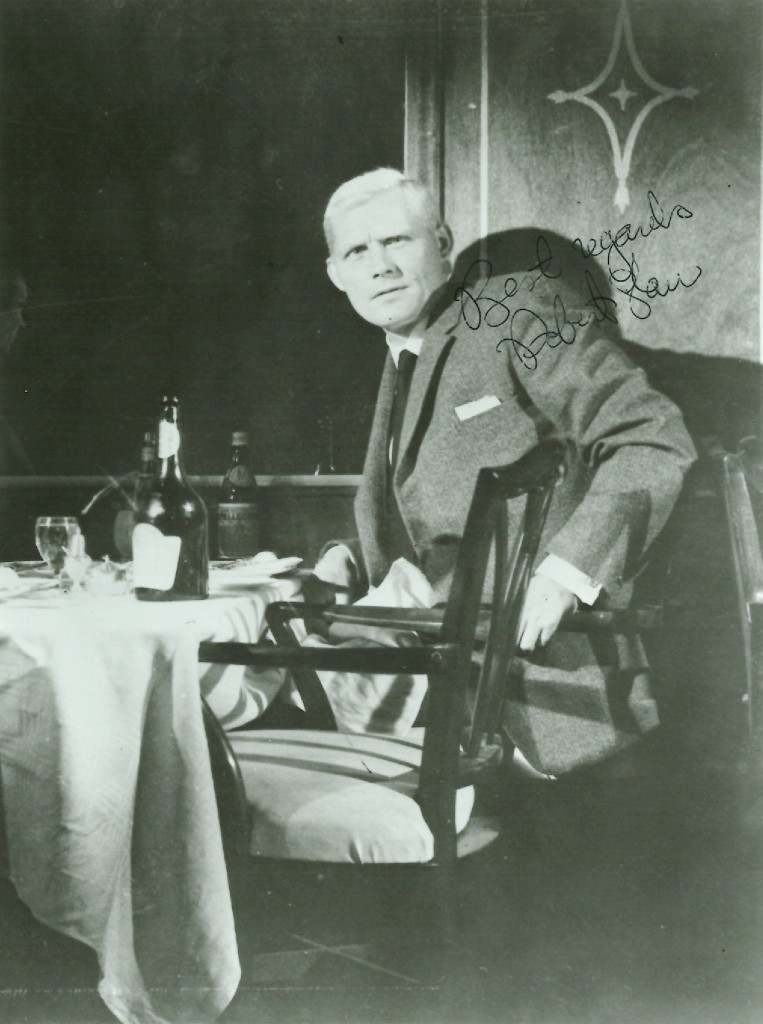

My favourite autograph and one of the rarest is of the brilliant actor Robert Shaw. He has starred in such magnificent movies as “Jaws”, “The Deep”, “The Sting”, “The Taking of Pelham 1…2…3..”, “A Man For All Seasons” and “From Russia With Love”. Sadly he died of a heart attack at his Irish home in Tourmakeady, Co Mayo in 1978 at the age of only 51. He was married to the beautiful Mary Ure(who starred in “Where Eagles Dare” with Clint Eastwood) who also died very young aged 42 in 1975.

TCM overview:

A rough-hewn British character actor who played more leading roles later in his career, Robert Shaw went from being typecast as tough-guy villains to proving his versatility in a wide range of performances. Shaw had his start on the stage in the late 1940s and quickly segued to the screen where he broke through as an assassin for SPECTRE in “From Russia with Love” (1963). But it was his Oscar-nominated turn as King Henry VIII in “A Man for All Seasons” (1966) that helped shed new light on the actor, leading to a variety of characters in films like “Battle of Britain” (1969), “A Town Called Hell” (1971) and “Young Winston” (1972). Shaw then entered his most fruitful period to play ruthless mob boss Doyle Lonnegan in “The Sting” (1973) and criminal mastermind Mr. Blue in “The Taking of Pelham One Two Three” (1974), which paved the way for his most iconic performance as salty Quint in Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws” (1975). From there, Shaw was a leading man in a number of major studio films like “Black Sunday” (1977), “Force 10 from Navarone” (1977) and “Avalanched Express” (1979). But at the height of his career, Shaw suffered a fatal heart attack. Whether on screen or as the author of award-winning novels, Shaw was a unique talent the likes of whom would not be seen again.

Born on Aug. 9, 1927 in Westhoughton, Lancashire, England, Shaw was raised by his father, Thomas, a physician, and his mother, Doreen, a former nurse. When he was seven years old, the family moved to Scotland and when he was 12, Shaw’s father – a manic depressive and alcoholic – committed suicide. As a result, the family moved to Cornwall where Shaw attended the independent Truro School and briefly taught school in Saltburn-by-the-Sea, before attending the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. In 1949, he made his stage debut with the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon and later in the year toured Australia with the Old Vic. Shaw soon made his London stage debut in a West End production of “Caro William” (1951) and a few years later, transitioned to the screen with minor supporting roles in “The Dam Busters” (1955) and “A Hill in Korea” (1956), before returning to the stage to star in his own play, “Off the Mainland” (1956). Following a turn in the British crime thriller “Man from Tangier” (1957), he spent 39 episodes as the lead pirate on the children-themed series “The Buccaneers” (ITV, 1956-57).

Following the show, Shaw went back to the big screen for small roles in “Sea Fury” (1958) and “Libel” (1959), before landing episodes of British series like “The Four Just Men” (ITV, 1959-1960) and “Danger Man” (ITV, 1960-68). After playing Leontes in the feature adaptation of “The Winter’s Tale” (1961), he played cunning SPECTRE assassin Red Grant in “From Russia with Love” (1963). At this point, Shaw became a published author with The Hiding Place (1960) and The Sun Doctor, the latter of which won the 1962 Hawthornden Prize. He next played King Claudius in Grigori Kozintsev’s adaptation of “Hamlet” (1964), the Ghost of Christmas Future in “Carol for Another Christmas” (1964), and a fictional colonel fighting in “Battle of the Bulge” (1965), an epic war film about the famed World War II battle starring Henry Fonda, Robert Ryan, Telly Savalas and Charles Bronson. In “A Man for All Seasons” (1966), Shaw was King Henry VIII to Paul Scofield’s Sir Thomas More and Orson Welles’ Cardinal Wolsey, a performance that earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor – the only such honor of his career.

Shaw went on to portray Gen. George Armstrong Custer in the critically derided Western “Custer of the West” (1967), before starring in William Friedkin’s adaptation of Harold Pinter’s “The Birthday Party” (1968). In the “Battle of Britain” (1969), Shaw was cast alongside British heavyweights like Laurence Olivier, Trevor Howard, Christopher Plummer, Michael Caine and Susannah York for this epic and surprisingly historically accurate depiction of England’s fight to stop the Luftwaffe from bombing Britain back to the Stone Age. That same year, he starred opposite Plummer in the historical drama “The Royal Hunt of the Sun” (1969), while the following year he had his first screenwriting credit with “Figures in a Landscape” (1970), wherein he played an escaped convict alongside Malcolm McDowell who try to escape from the secret police of an unidentified totalitarian country. Following a leading performance in the little known Western “A Town Called Hell” (1971), he was Lord Randolph Churchill, father to Winston Churchill (Simon Ward) in “Young Winston” (1972), a British-made biopic about the early years of the future prime minister.

Though a well-known actor both in Britain and America, Shaw had yet to hit his most fertile period, which commenced with his turn as ruthless Irish mob boss Doyle Lonnegan in “The Sting” (1973), who becomes the target of a long con by two confidence men (Paul Newman and Robert Redford) after he kills their friend and mentor (Robert Earl Jones). Shaw’s performance as the barely contained Lonnegan was a terrific counterpoint to Newman’s devil-may-care turn as expert con artist Henry Gondorff, which was perfectly exemplified in a card game where Lonnegan is out-cheated by Gondoff – one of the more memorable scenes of this multi-Oscar winning film. Shaw next played Mr. Blue, a criminal mastermind who leads a gang of thieves into a New York subway to steal $1 million in the commercial and critical action hit “The Taking of Pelham One Two Three” (1974). Standing in Mr. Blue’s way is a gruff, but determined transit cop (Walter Matthau), who contends with the chaos of multiple city agencies and a reluctant mayor (Lee Wallace) while trying to figure out just how the gang plans to escape the subway tunnel while surrounded by police.

The following year, Shaw delivered his most iconic performance in Steven Spielberg’s “Jaws” (1975) playing Quint, a salty old shark fisherman who hunts down a killer great white with a landlubber police chief (Roy Scheider) and a know-it-all marine biologist (Richard Dreyfuss). Shaw’s turn as the grizzled seafarer was the film’s most memorable, particularly in his confrontations with Dreyfuss’ bookish biologist and in his haunting recount of the sinking of the doomed U.S.S. Indianapolis. The movie was a monster hit and the highest-grossing film ever made at the time, making “Jaws” Shaw’s most successful film on all fronts. From there, Shaw starred alongside James Earl Jones as two pirates in “Swashbuckler” (1976) and played the Sheriff of Nottingham to Sean Connery’s Robin Hood in “Robin and Marian” (1976). He went on to search for sunken treasure with Nick Nolte and Jacqueline Bisset in “The Deep” (1977) and was an Israeli military officer trying to thwart a crazed Vietnam vet (Bruce Dern) from blowing up the Super Bowl in “Black Sunday” (1977). Shaw next starred in the sequel “Force 10 From Navarone” (1977), taking over the Gregory Peck role as the leader of a special forces group that tries to blow up a bridge with a traitor in their midst. After completing the filming of “Avalanche Express” (1979), where he played a Russian general who defects to the United States, Shaw suffered a sudden heart attack while home in Tourmakeady, County Mayo, Ireland. He was only 51 years old.

By Shawn Dwyer