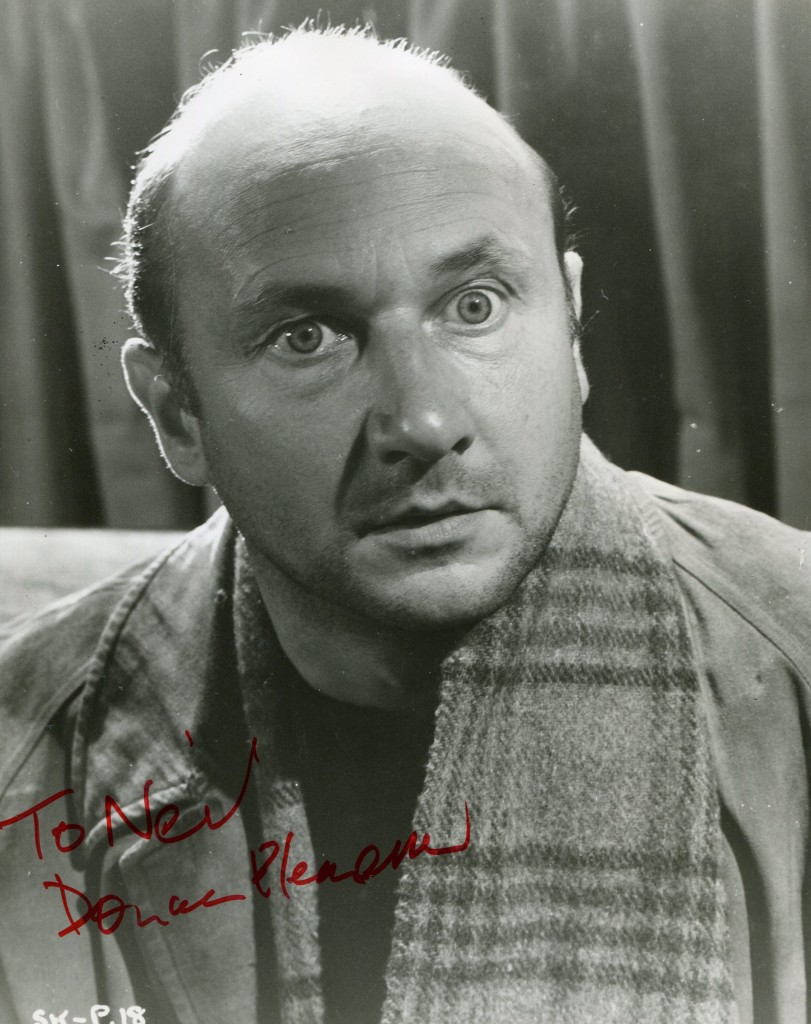

The odd man out: master of low cunning and of sinister poise, a threat to anyone’s peace of mind, his own as often as not. He specialised in conspicuous self-effacement. And if his roles happened not to be sinister or self-effacing he made them so. His acting was decisive, distinct, disconcerting and dreadful in the sense that he filled with fascinated fear those who watched him. Both on stage, and off.

He was odd the first time I ever saw him nearly half a century ago in the golden days of the Arts Theatre. It was a play by Jean-Paul Sartre, Huis Clos, done into English as Vicious Circle and acted by Alec Guinness. Beatrix Lehmann, Betty Ann Davies. Peter Brook, in his twenties, directed. Pleasence was the watcher, the bell-hop, a sort of Buttons. A tiny part and supposedly self-effacing but of course unforgettable, like most of his theatrical acting. The knack of being glaringly off-centre rarely failed to catch the imagination even if the knackgrew a touch predictable.

Pleasence could be pleasant. After spells in rep at Birmingham and Bristol he was charming for example as the timorous North Country shoemaker Willie Mossop in Hobson’s Choice (1952) – again at the then invaluable Arts – and after tiny parts in London and New York with Olivier’s company in Caesar and Cleopatra and Antony and Cleopatra had a play of his own, Ebb Tide (1952), acted at the Edinburgh Festival which was judged good enough to go to the Royal Court.

Pleasence went to Stratford-upon-Avon and turned up as Lepidus in the Redgrave-Ashcroft Antony and Cleopatra. He was the Dauphin to Dorothy Tutin’s Joan of Arc in another Brook production, Anouilh’s The Lark (1956); but the part that made him famous was the tramp in Pinter’s The Caretaker (1960), again at the Arts.

No one who saw him is likely to forget the cringing, whining wheedling, fearful and fearsome ambiguity of that tramp with his dreams of getting down to Sidcup. The cunning way in which he dealt with those two strange brothers in those seedy premises, andhis beady-eyed resolve to have things his way brought the play into sinister but comic focus.

Pleasence’s voice, at once incisive, rasping, calculated, cold, sounded like iron filings. When the play went to the West End and thence to Broadway he went with it. He had been perfect. He had made the oily, wily, anxious little character his own; and when the play was revived in 1990 there was no question that the actor who created the part should play it again. He did so superbly.

He loomed impressively in other West End plays. As Anouilh’s Poor Bitos (1967), solitary, self-pitying, eery, he sent shivers down most spines and as the Eichmann-type character in Robert Shaw’s The Man in The Glass Booth (1967, directed by Pinter) he went back to Broadway and won the London Variety Award for Stage Actor of the Year (1968).

Variety? Pleasence’s talents as an actor “did not that way tend”; but so what? His line was unrivalled in its nervy disclosure of fearful imaginings and private suffering, unrelieved solitude and sweaty suspicion. Small wonder if Pinter chose him againfor a double bill of his plays, The Basement and Tea Party in 1970 at the Duchess, where The Caretaker had thrived a decade earlier.

When however Pleasence had the misfortune to experience in Simon Gray’s Wise Child the kind of swift failure in which Broadway specialises – he played the transvestite role of Mrs Artminster created in London by Alec Guinness – he turned more and more totelevision and the cinema. He always dreaded being out of work.

Having settled for the screen, big or small, he might not have got the kicks which the theatre brought him (and us) but his nightmare of unemployment receded. His love of the stage had once or twice cost him dear. Had he not turned down a fortune from a film offer to play the title role in The Caretaker? Had he not gone on to film it for nothing when more Hollywood gold had beckoned?

Still, his re-creation of his original role on stage five years ago in a revival of The Caretaker showed that at 70 he had lost none of that indefinably eery power to give us the shivers with a blue-eyed stare. Had it come from art alone or from his wartime experiences?

Having registered as a conscientious objector, he joined the RAF when he saw how fellow-pacifists regarded without apparent emotion or guilt the Nazi bombing of London; and as a member of a bomber’s crew he flew 60 missions over Germany before being shotdown and imprisoned.

Adam Benedick Well-known as a star of the cinema screen, giving menacing performances in the title role of Dr Crippen (1962) and as the psychiatrist Sam Loomis in the Halloween series of supernatural chillers, Donald Pleasance also brought his sinister looks to television in a variety of productions, from a controversial Fifties version of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four to appearances in Armchair Mystery Theatre and The Falklands Factor, writes Anthony Hayward. His piercing, psychotic stare, hushed voiceand bald head were his trademarks, in almost 200 films and as many television programmes over half a century.

Born in Worksop, Nottinghamshire, the son of a station master, Pleasance followed his father into the railways on leaving school by becoming clerk-in-charge at Swinton station, in south Yorkshire, but his ambition was to be an actor. When the chance came, with Jersey Rep in 1939, he started as an assistant stage manager, before making his debut as Hareton in Wuthering Heights. His first London stage appearance was as Valentine in Twelfth Night, three years later.

Shortly afterwards, he joined the RAF for war service as a radio operator and, after being shot down, was a prisoner-of-war from 1944 until 1946, when he returned to the theatre. After his successful stage work with Laurence Olivier in New York and at the Royal Court, London, and Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, Pleasence made his name as a film actor.

He made his big-screen debut as Tromp in the 1954 picture The Beachcomber and followed it with such notable films as Look Back in Anger (1959), The Flesh and the Fiends (1960, as a 19th-century grave-robber), Spare the Rod (1961, as an embittered headmaster with a penchant for corporal punishment), Dr Crippen (which established him as a brilliant player of evil roles), The Great Escape (1963, as Blythe, the forger of visas and other documents) and The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965).

However, his prolific screen appearances – which in some years meant he starred in half-a-dozen pictures – were not all successful. “I make films for money,” he once said. “I never, ever watch them.” In the James Bond feature You Only Live Twice (1967),he played the badly scarred, wonky-eyed arch-villain Ernest Blofeld, the evil boss of SPECTRE, although he was subsequently considered not ideal for the role and replace by Telly Savalas and Charles Gray, who dispensed with the facial disfigurement.

Pleasence was back on top form in Henry VIII and his Six Wives (1972), in the role of Thomas Cromwell, gleefully weeding out opponents to the King’s divorce. He appeared alongside Michael Caine in both Kidnapped (1971, playing the niggardly Uncle Ebenezer in the Robert Louis Stevenson classic) and the spy thriller The Black Windmill (1974, as the twitchy paymaster). Pleasence was given a new lease of life as Dr Sam Loomis, the psychiatrist haunted by evil, in the Halloween series of supernatural horror films, starting in 1978, and later appeared in Woody Allen’s Shadows and Fog (1991).

Although his television appearances were infrequent after he gained film stardom, they were many and usually made their mark. He made his debut as early as 1946, in I Want to Be A Doctor, and eight years later won acclaim for his performances in the BBC’s 1984, alongside Peter Cushing. The adaptation, by Nigel Kneale, author of the Quatermass Experiment, caused an outcry among viewers because it was screened on a Sunday evening, a time when they were used to enjoying more sedate dramas.

Later Pleasence became known as the presenter and producer of Armchair Mystery Theatre for several years (starting in 1960), also acting in some episodes. He went on to perform on American and Canadian television. appearing in episodes of The Twilight Zone, Orson Welles’s Great Mysteries and Columbo. He also appeared in Centennial (1978-79), as Samuel Purchase in the series based on James Michener’s epic novel, Dennis Potter’s Blade on the Feather (1980), as an ageing Establishment figure suddenly exposed as a homosexual and Soviet spy – in the wake of the Anthony Blunt scandal – The Barchester Chronicles (1982), in which he gave a touching performance as the Rev Septimus Harding in a seven-part adaptation of Trollope, The Falkland s Factor (1983), DonShaw’s controversial Play for Today that featured him as Dr Samuel Johnson, who opposed a Falklands war in 1770 when the Spanish attempted to invade the islands and oust the British.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.