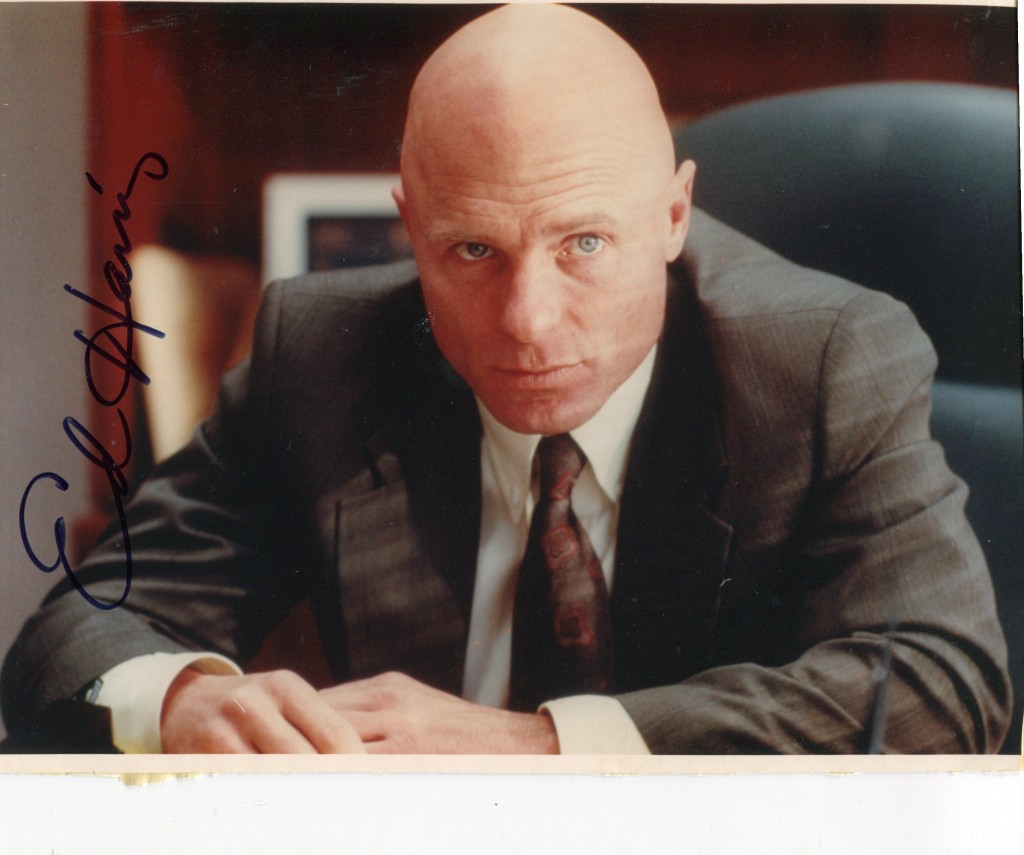

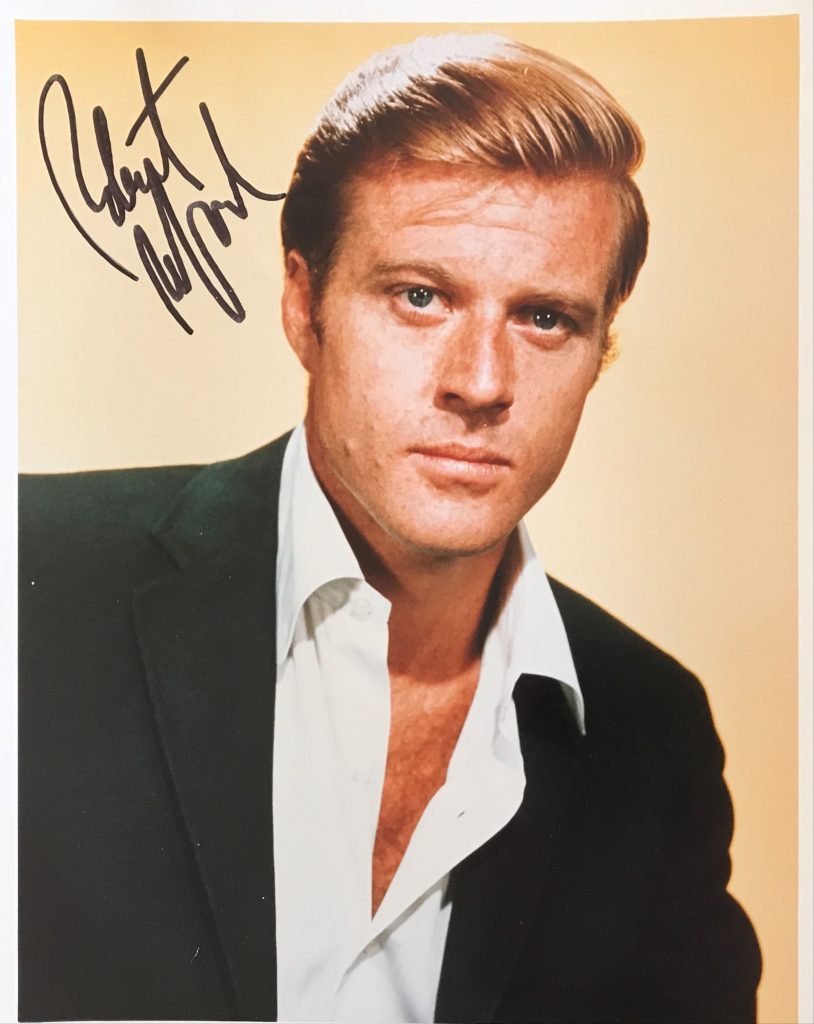

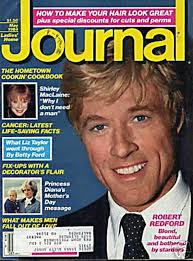

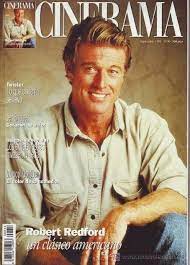

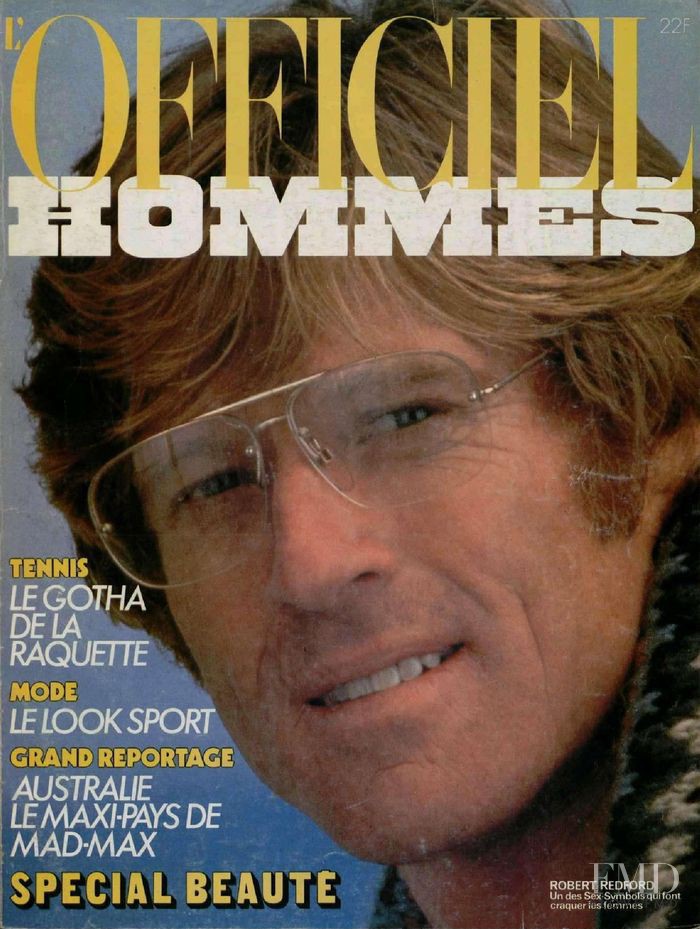

Robert Redford’s all-American blond good looks and subtle, sardonic sense of humor made him one of the most popular leading men of the late 1960s into the 1970s in features like “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969), “The Sting” (1973) and “All the President’s Men” (1976). Along with his peers Warren Beatty and Paul Newman, he was one of the rare movie icons who could balance being both a respected actor as well as undeniable sex symbol – seen most effectively with his heartfelt turn in “The Way We Were” (1973) – a timeless romance which caused many a female heart to flutter through the years. Growing into his age gracefully, he branched out, wisely parlaying his acting fame into an Oscar-winning career as a director, and becoming a patron saint of sorts to independent filmmakers by establishing the Sundance Film Festival and Sundance Institute, as well as numerous critically acclaimed projects that supported original moviemaking outside the Hollywood system.

Redford’s early years showed a distinct rebellious streak that carried well into adulthood. The son of a Standard Oil accountant, Charles Robert Redford, born Aug. 18, 1936, lost his mother while still in his teens, which spurred a rash of adolescent misdemeanors, as well as the loss of a baseball scholarship to the University of Colorado due to alcohol-related infractions. He departed the school in 1957 to attend the Pratt Institute of Art before taking a tour of Europe to explore his painterly side. He returned to the States and promptly decided on a career in acting, which he studied at the acclaimed American Academy of Dramatic Arts. In 1958, Redford married Lola Van Wagenen, with whom he had four children between 1959 and 1970 (the first, Scott, died from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in 1959).

Redford’s tall frame and physical appeal made him a natural for television and theater producers looking for upstanding young men, so he found himself working regularly on quality shows like “Playhouse 90” (CBS, 1956-1961), in which he appeared in the series’ finale episode, Rod Serling’s “In the Presence of Mine Enemies;” Sidney Lumet’s TV presentation of “The Iceman Cometh” (1960) with Jason Robards; as well as quick paychecks like the game show “Play Your Hunch” (NBC, 1960-1962). He also worked extensively on stage during this period, with his Broadway debut coming in 1959’s “Tall Story” (he also had an uncredited role in the 1960 film version) and he eventually worked his way up to major productions like Neil Simon’s “Barefoot in the Park” in 1963.

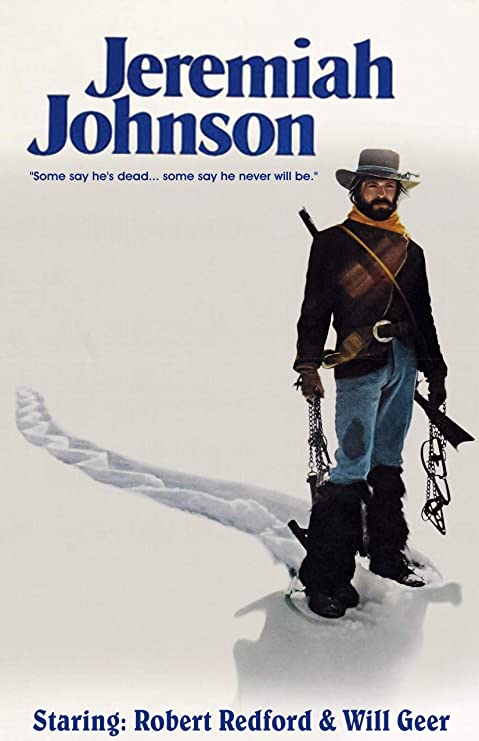

An Emmy nod for an episode of “Alcoa Premiere” (NBC, 1961-63) preceded his first substantial film role in “War Hunt” (1962), a Korean War drama about a psychotic soldier (John Saxon) in an Army platoon. Also making his debut in the project was future filmmaker Sydney Pollack, a longtime friend of Redford’s and his director on several projects, including “Jeremiah Johnson” (1972) and “The Way We Were.” More television followed – including three stints on “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” (NBC, 1955-1965); “The Twilight Zone” (CBS, 1959-1964) in a memorable turn as the Angel of Death; and “The Defenders” (CBS, 1961-65) – but he graduated to regular film work after his success in “Barefoot in the Park.” What followed was a string of roles in solid if unremarkable features that played up Redford’s looks rather than his talent. He was a ’30s-era movie star and closeted homosexual in “Inside Daisy Clover” (1965); a Southern prison escapee targeted by a conflicted sheriff (Marlon Brando) in Arthur Penn’s “The Chase” (1966); and a railway representative who falls for a flirtatious Natalie Wood in “This Property Is Condemned” (1966), with Francis Ford Coppola adapting the Tennessee Williams play for director Sydney Pollack.

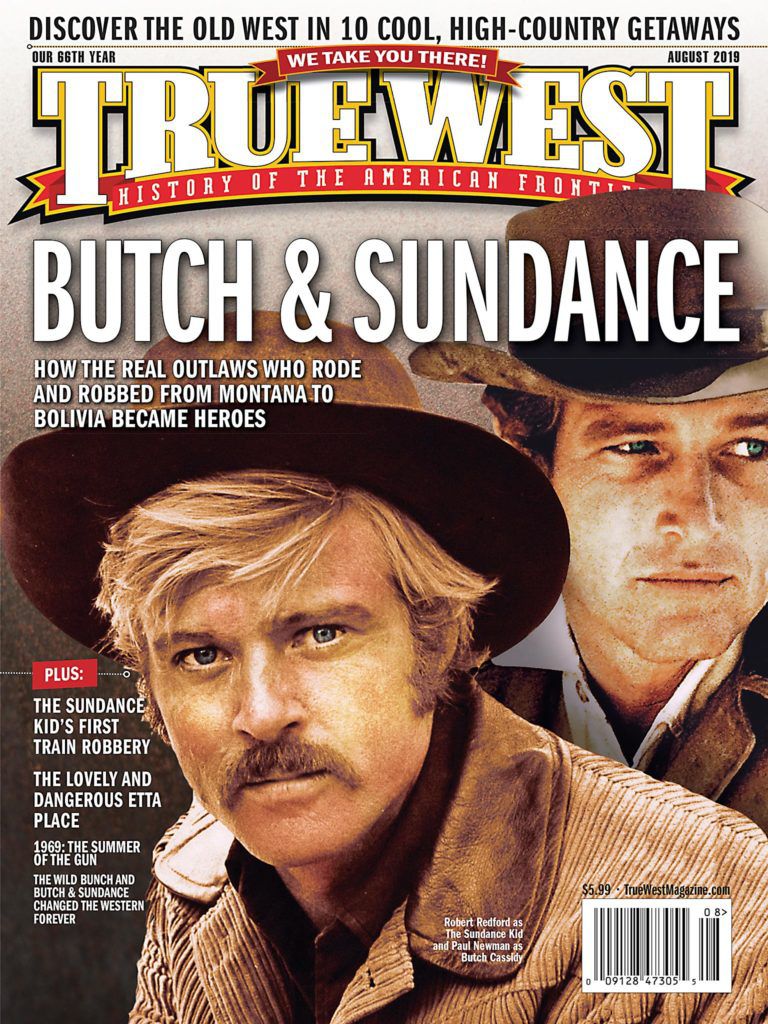

Sensing that his career was heading into stagnant waters, Redford decided to pass on projects like “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” (1966) and “The Graduate” (1967) – both of which would have perpetuated his streak of bland leading men; Redford was holding out for something more substantial. His deliverance came in the form of George Roy Hill’s Western adventure, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969), which partnered him with Paul Newman as the rowdy title outlaws. Redford was not favored for the role by 20th Century Fox, but Hill was adamant about him in the role of the Sundance Kid. The result was a blockbuster hit and a multiple Oscar winner, as well as the second act of Redford’s career. His turn as the breezy, death-defying Kid redefined his screen persona, and gave him a name on which to hang many of his future endeavors.

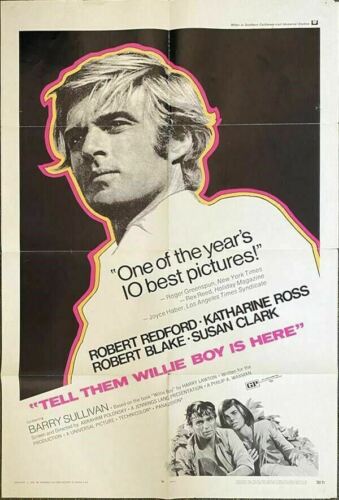

After “Sundance,” Redford embarked on a personal crusade to participate in projects that emphasized quality over concept and star power. His efforts to this end, while not always successful at the box office, were a remarkable string of mature and involving dramas, including “Downhill Racer” (1969), with Redford as an egotistical skier who clashes with coach Gene Hackman (Redford also served as executive producer); “Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here” (1969), with Redford as a sheriff on the trail of Indian Robert Blake, who has killed his white lover’s father; and “Little Fauss and Big Halsey” (1970), with Redford and Michael J. Pollard as motorcycle racers. “The Hot Rock” (1972) was a breezy comedy based on a Donald Westlake novel, with Redford leading an inept team of jewel thieves, but it failed to score with audiences. More successful was “Jeremiah Johnson,” a fact-based Western for Sydney Pollack about a vengeful mountain man (Redford) hunting the Indian tribe that butchered his family, and “The Candidate” (1972), a darkly comic political satire about a lawyer (Redford) corralled into running for a senatorial seat by a savvy campaign expert (Peter Boyle). In each case, Redford stepped as far away from his previous Hollywood image as possible, succeeding in winning both critical and moviegoer praise for these risky moves.

The banner year 1973 marked the beginning of Redford’s reign as Hollywood’s top audience draw with back-to-back blockbusters. “The Way We Were” reunited him with Pollack for a tear-jerking period romance between WASPy collegian Redford and a political activist (Barbra Streisand). The film yielded a massive chart hit with Streisand’s theme song, and set a new standard for Hollywood romances to follow. Redford then paired again with Hill and Newman for “The Sting,” a sparkling caper comedy about two con men who aspire to fleece a mob boss (Robert Shaw). The picture, which touched off a modest revival of the music of jazz era composer Scott Joplin, pulled in $160 million at the box office and gave Redford his sole Oscar nomination for acting.

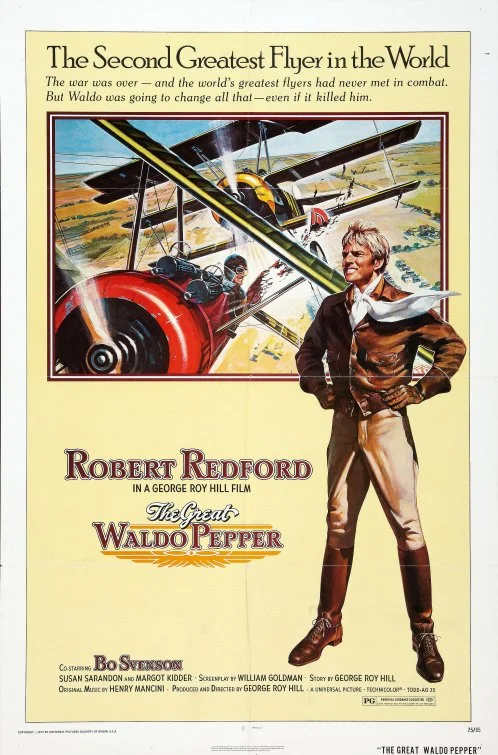

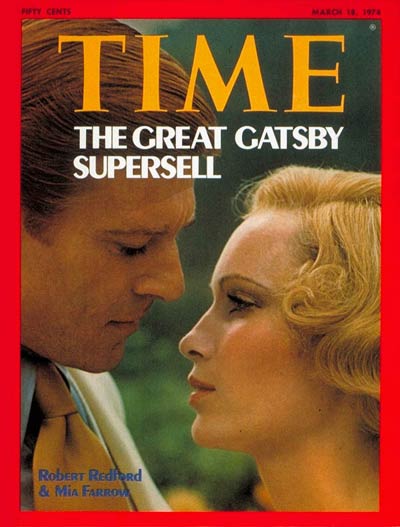

After a slight stumble as Jay Gatsby in Jack Clayton’s flawed “The Great Gatsby” (1974) and as a barnstorming trick pilot in George Roy Hill’s “The Great Waldo Pepper” (1975), Redford enjoyed a second two-fer of hits with “Three Days of the Condor” (1975) and “All the President’s Men” (1976). The former was a tense spy thriller from Sydney Pollack about a CIA operative (Redford) on the run from his own agency, while the latter was a superior political drama based on the investigation of The Washington Post reporters Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) and Bob Woodward (Redford) into the Watergate break-in, which eventually lead to the ousting of President Richard Nixon. The film earned several Academy Awards and yielded a substantial hit for Redford’s production company, Wildwood films, which helped bring the picture to the screen. After a supporting role in Richard Attenborough’s massive, all-star World War II drama “A Bridge Too Far” (1977), Redford ended the 1970s on a high note with Sydney Pollack’s “The Electric Horseman” (1979), an engaging hit about a failed rodeo champion searching for dignity.

Redford made his directorial debut in 1980 with “Ordinary People,” a gripping drama about a family struggling to come to grips with their son’s depression and guilt over the death of a sibling. Redford drew remarkable performances from his cast, especially Mary Tyler Moore as a brittle grieving mother, and earned an Oscar for Best Director. The following year, he founded The Sundance Institute, a non-profit organization built to assist aspiring filmmakers and theater artists in developing their talent. Located in Park City, UT, near where he had maintained a home since the early ’60s, Redford soon expanded the institute’s influence to the Utah/U.S. Film Festival, which was transformed into the Sundance Film Festival in 1985 and became one of the leading film events for independent filmmakers in America. Years later, a cable channel and chain of theaters – all bearing the Sundance brand – were launched in 1996 and 2005, respectively.

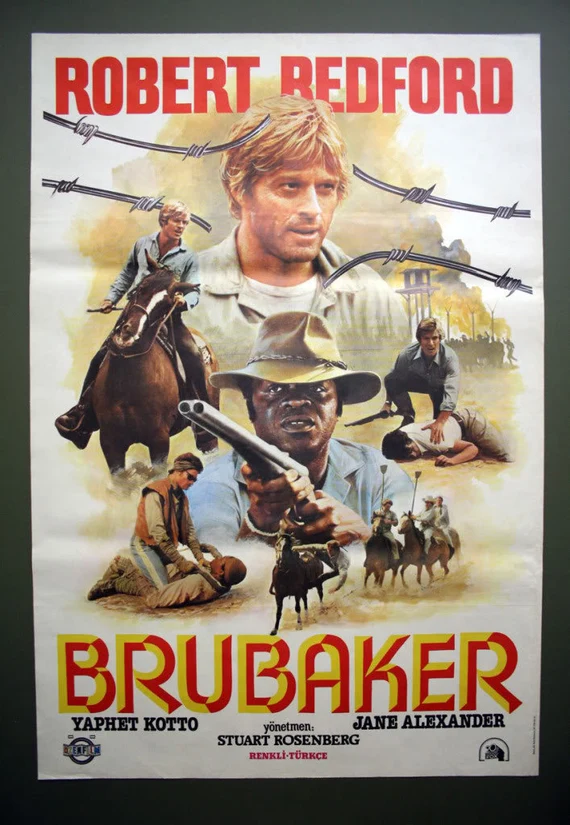

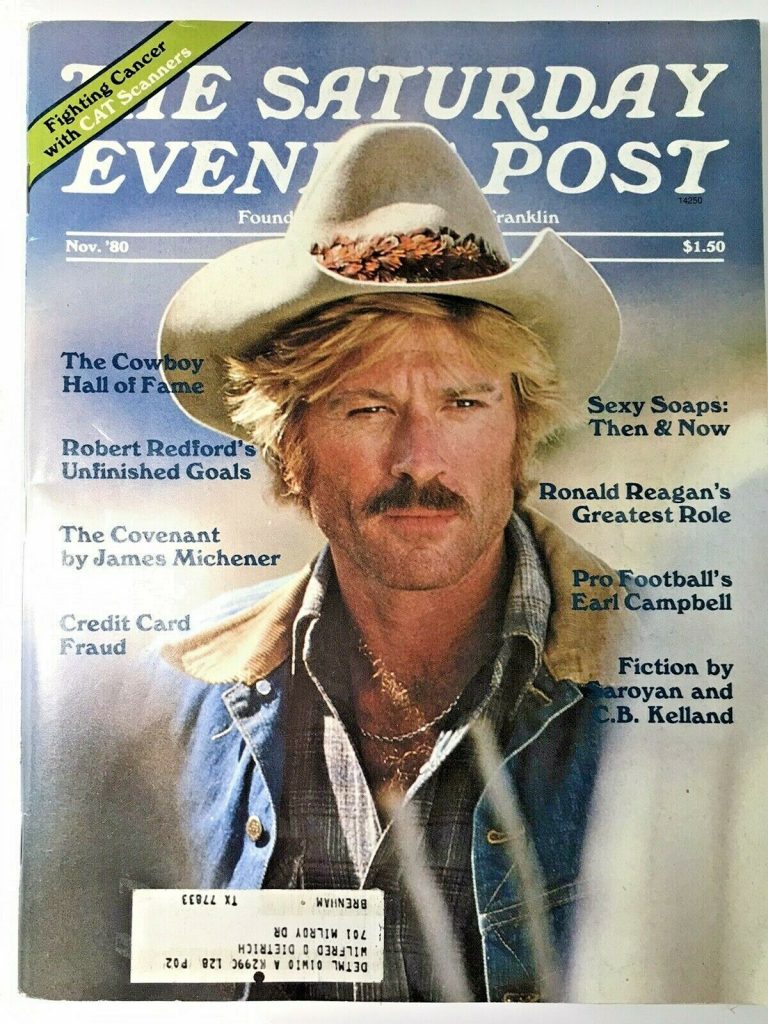

Redford continued to act throughout the 1980s, though the quality of his pictures waxed and waned throughout the decade. Hits included “Brubaker” (1980), a tough drama about a prison warden who impersonates an inmate to investigate the conditions in his own facility; Barry Levinson’s entrancing baseball fantasy “The Natural” (1984), with Redford as a former golden boy player who returns to the majors to give hope to a struggling team; and Sydney Pollack’s sweeping, Oscar-winning period romance “Out of Africa” (1985), with Redford as a big-game hunter in Africa who romances Danish author Karen Blixen (Meryl Streep). Less successful were Ivan Reitman’s comedy “Legal Eagles” (1985), which floundered at the box office and arrived on syndicated television with a completely different ending, and Redford’s sophomore directorial effort, “The Milagro Beanfield War” (1988), which earned mixed reviews and middling box office returns. Redford also divorced his wife in 1985 and courted several notable women, including his “Milagro” star Sonia Braga, before settling into a long term relationship with German artist Sibylle Szaggars in 1996.

The 1990s saw Redford balancing acting with behind-the-camera work on a regular basis, as well as maintaining his growing Sundance empire. “Havana” (1990) was a failed period drama, with Redford as an American gambler who is drawn into the Cuban revolution of 1960, while “Sneakers” (1992) was an entertaining comedy/drama with Redford as the leader of a team of rogue security operatives – including Sidney Poitier, Ben Kingsley, River Phoenix and Dan Aykroyd – who tangle with nefarious government types. “Indecent Proposal” (1993) was perhaps the most dreadful film on Redford’s CV – directed by Adrian Lyne, it was exploitation tricked out as a concept movie, with Redford as an amoral millionaire who offers a money-strapped couple (Demi Moore and Woody Harrelson) a fortune if he can sleep with the wife for one night. “Up Close and Personal” (1996) was a glossy and fictionalized take on the life of news reporter Jessica Savitch with a script by Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne. The former film made a mint; the latter film was memorable only for spawning the Celine Dion soundtrack single, “Because I loved You” – certainly not for any chemistry or lack thereof between the veteran Redford and the much younger Michelle Pfeiffer.

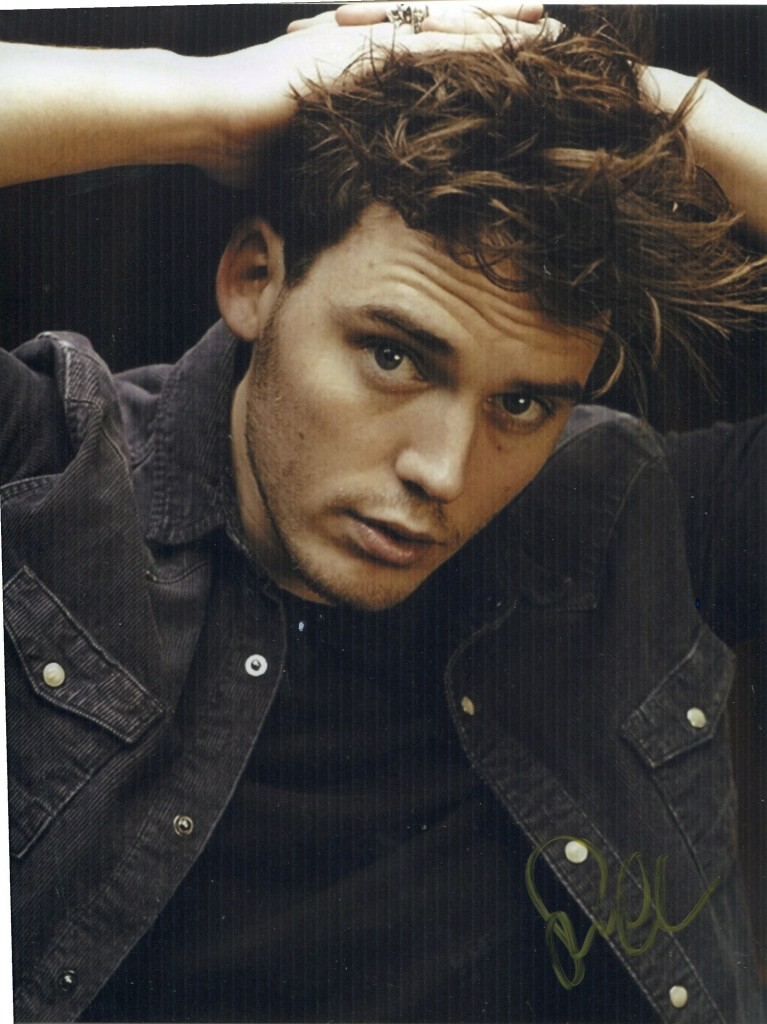

Redford’s efforts as director and producer during this period were more rewarding to audiences and to his own career. Redford directed, produced, and narrated, “A River Runs Through It” (1992) a moving period drama about two young men (Brad Pitt and Craig Sheffer) coming of age during the first World War and Great Depression. Exceptionally well performed by its cast, it earned an Oscar for Best Cinematography, as well as a director nomination for Redford. He followed this with “Quiz Show” (1994), a fascinating drama about the participants in the infamous cheating scandal that rocked the TV game show boom of the 1950s. Though the film struggled to find a substantial audience, it was lauded for its dramatic quality and received four Oscar nominations, including Best Director for Redford and Best Adapted screenplay for Paul Attanasio. And 1998’s “The Horse Whisperer” marked the first time Redford directed, produced and starred in the same picture. The film, about a horse trainer (Redford) who helps a young rider (Scarlett Johansson) recover from a traumatic injury, received mixed reviews but scored major ticket sales. Redford also served as producer for numerous independent features during the 1990s, including Michael Apted’s documentary “Incident at Oglala” (1992), which he also narrated; Edward Burns’ “She’s the One” (1996); the HBO Native American series “Grand Avenue” (1996); and “Slums of Beverly Hills” (1998). The ’90s also saw him bring home a flurry of awards, including the Cecil B. DeMille Award in 1994 and the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Screen Actors Guild in 1996.

Redford’s next directorial effort, “The Legend of Bagger Vance” (2000), starred Will Smith as a mystical golf caddy who aides a struggling duffer (Matt Damon) to recover his game and his self-confidence. The film performed well at the box office, due mainly to its two leads’ star appeal, but received middling reviews. Redford himself made sporadic film appearances in Tony Scott’s action hit “Spy Game” (2001) and “The Last Castle” (2001) – the latter of which tanked despite the presence of James Gandolfini and Mark Ruffalo. More successful was “The Motorcycle Diaries” (2004), which Redford produced, as well as several TV-movie adaptations of Tony Hillerman’s Native American mysteries – including “Skinwalkers” (2002), “Coyote Waits” (2003), and “A Thief of Time” (2004), which aired on PBS. For his numerous contributions to independent cinema, Redford was given an honorary Oscar in 2002. In 2005, Redford was honored alongside Tony Bennett, actress Julie Harris, and Tina Turner by the Kennedy Center.

Redford’s turns as a leading man continued into the 21st century, though they became harder to find. The well-received thriller “The Clearing” (2004) barely saw a theatrical release, and while Lasse Hallstrom’s “An Unfinished Life” gave Redford a plum role as a cantankerous rancher who is forced to reconcile with his daughter-in-law (Jennifer Lopez), the film vanished at the box office due to the restructuring of its distributor, Miramax. He later lent his gravelly tones to the horse Ike in the live-action/CGI remake of “Charlotte’s Web” (2006) and returned to directing with the politically-charged drama “Lions for Lambs” (2007), co-starring Meryl Streep and Tom Cruise (who also produced under his new shingle at United Artists). The picture opened to moderate business and less-than-enthusiastic reviews. Redford worked both sides of the camera in the sociopolitical drama “The Company You Keep” (2013), directing a script by Lem Dobbs (“The Limey”) and starring as a former member of a 1960s radical group in hiding whose new identity is threatened with exposure by a young investigative journalist (Shia LeBeouf). He followed that with the claustrophobic “All Is Lost” (2013), in which he played an unnamed man whose solo ocean voyage becomes a fight for survival.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.