“Just as the economic and social climate of Broadway produced the theatre enterprises known collectively as ‘off-Broadway’, so in the late 50s and 60s there grew up hat might be called ‘fringe Hollywood’ – not quite ‘underground’, but with a clear demarcation line between it’s product and that of the major studios. The films churned out were the Cinerellas of the industry though none of them went to the ball. They had in common only low budgets – some of them miniscule – with the usual concomitant, the desire for a quick buck. Some of them had ideas and energy, much of it misdirected. A few of them featured Jack Nicholson, the only major actor to emerge from the outer-stage into the bright Hollywood spotlight. As soon, indeed, as he appeared in ‘Easy Rider’, half-way through, there was no question that there was an authentic star- the noun might be wrong but this was a player of enormous charm and magnetism. As long as he was on screen, he diverted attention from the two leading players, Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper. They represtented, perhaps better than any, the new breed of Hollywood player and Nicholson willy-nilly represented the sort of personality we are stuck with until the day that all men are flat, alike and automated” – David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars- The Independent Years”. (1991).

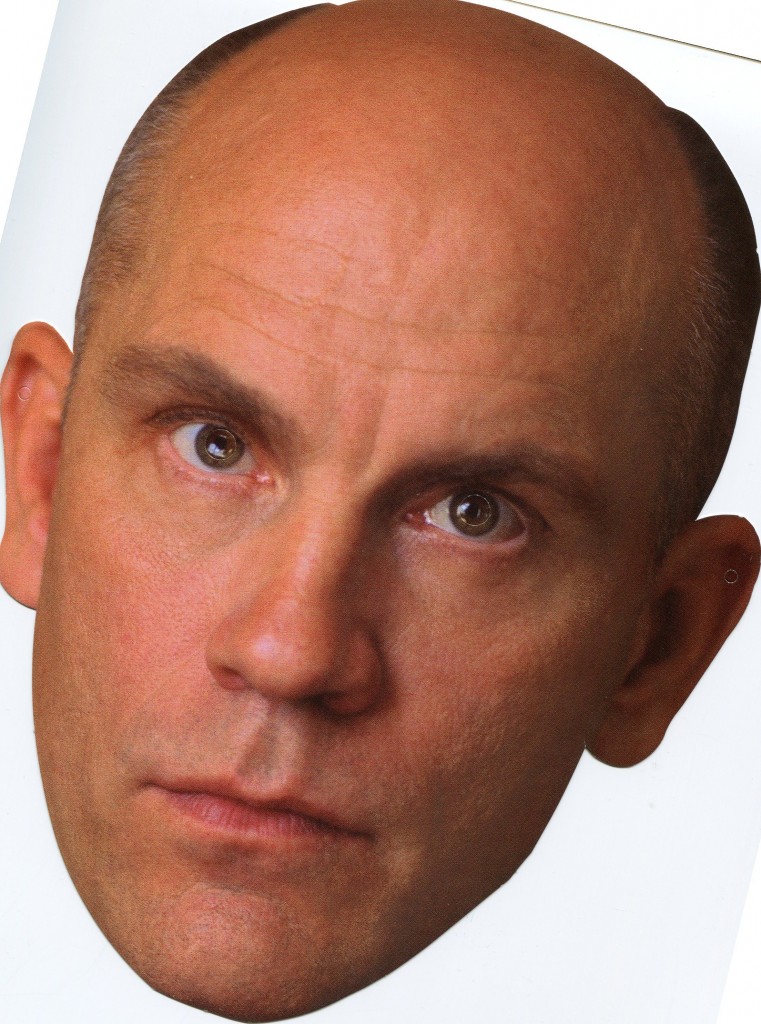

Jack Nicholson with his killer smile and drawling voice has become a true icon of American cinema. He has won Oscars in the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s. My own favourite of his movies are “Five Easy Pieces” where he plays the oil rig drifter Bobby Dupea and the private investigator J.J. Gittes in “Chinatown”.

Perhaps no other actor of his generation made more of a lasting impression than Jack Nicholson. Over the course of several decades, Nicholson delivered one sterling performance after another in films that have long been considered as being some of the greatest ever made. Though he got his start with low-budget king Roger Corman in the late-1950s, the actor eventually made his mark with a memorable supporting role in the iconic counterculture road film, “Easy Rider” (1969). Thanks to that Oscar-nominated performance, Nicholson embarked on a fruitful decade of work that ultimately cemented his place in cinematic history, starting with a shaded portrayal of a man searching for what went wrong with his life in “Five Easy Pieces” (1970). But it was his performance as the dogged private detective Jake Gittes in “Chinatown” (1974) that turned the already successful actor into a legend, which he followed with perhaps his most enduring film, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975). From there, Nicholson became noted for his bombastic and over-the-top performances, which sometimes hampered the actor into being confined to “Jack” roles that limited his choices, as happened in “The Shining” (1980). This persona was put to excellent use in both “The Witches of Eastwick” (1987) and “Batman” (1990), while he managed to balance out such roles with a return to finer, more nuanced performances in “Terms of Endearment” (1987) and “As Good As It Gets” (1997), all of which underscored Nicholson’s place in at the top of the Hollywood pantheon.

Born on Apr. 22, 1937 in Neptune, NJ (or New York, NY or Manasquan, NJ – sources differ) Nicholson was raised in a broken home that later proved to be not all that it seemed. Nicholson grew up believing that his grandmother, Ethel, was in fact his mother; around 1975, Nicholson learned that his alleged sister, June, was actually his mother – she was a chorus girl in New York who became pregnant with him in a time and place where having a child so young would have shamed the family. Why and how the rouse was maintained until after both had died remained a mystery to Nicholson, who later claimed to have been relieved when he found out. Meanwhile, he never knew for certain who his father was – showman Donald Furcillo and June’s manager Eddie King eventually surfaced as candidates, but Nicholson was content to decline pursuing confirmation. Despite his complicated domestic situation, Nicholson grew up in a modest and stable home. He attended Manasquan High School, where he was voted class clown, and later both a theater and drama award were named after him.

Upon graduating high school, Nicholson rejected an engineering scholarship and went to Los Angeles, where June had relocated, staying after landing a job as a mail room gofer for Hanna-Barbera at MGM. He also began taking acting classes with Jeff Corey, where he met fellow up-and-coming actors Sally Kellerman, James Coburn and Robert Towne, future scribe of “Chinatown.” He soon made his film debut in the Roger Corman-produced crime thriller, “Cry Baby Killer” (1958), playing a young delinquent who kills a thug out to do him harm, who then flees to a local drive-in where he takes hostages and eventually creates a media firestorm. He continued his collaboration with Corman, who directed him in three early horror films, including “The Little Shop of Horrors” (1961), “The Raven” (1963) and “The Terror” (1963) – the latter two being filmed within days of each other, and using the same sets. Not content with just acting, Nicholson shared his first screenwriting credit with Don Devlin on Jack Leewood’s political thriller “Thunder Island” (1963). Nicholson returned to acting in Monte Hellman’s World War II actioner “Back Door to Hell” (1964), then scripted the director’s Philippine adventure yarn about two divergent men surviving the jungle after a plane crash in “Flight to Fury” (1966).

Journeying to the Utah desert to make back-to-back films, Nicholson starred in a pair Hellman’s existential Westerns “The Shooting” (1966) and “Ride the Whirlwind” (1966), the latter of which he also co-wrote and served as a producer on. Though not yet a household name, the actor was fast becoming a prominent force both in front of and behind the camera. After he wrote Corman’s psychedelic odyssey, “The Trip” (1967), a psychological drama about a commercial director who ingests LSD, he teamed up with first-time director Bob Rafelson to produce and co-write “Head” (1968), a plotless, but nonetheless visually interesting satirical look at the music industry as seen by The Monkees. But it was his supporting role as George Hanson, a hard-drinking Southern lawyer, in the iconic road movie “Easy Rider” (1969) that earned Nicholson widespread attention. Replacing actor Rip Torn – who abandoned the part written for him after a heated argument with director-star Dennis Hopper that ended with a the latter allegedly drawing a knife – Nicholson firmly established himself as an actor of caliber with a performance that earned several critic’s awards and a nomination for Best Supporting Actor at the Academy Awards.

Following his triumph with “Easy Rider,” Nicholson entered the 1970s poised to become a major star. Arguably the best decade of his career, Nicholson embarked on a series of iconic films that forever cemented him in the pantheon of Hollywood’s finest actors. He started with “Five Easy Pieces” (1970), a low-budget, European-style psychological drama that depicted Nicholson as a former musical prodigy-turned-oil rig worker who goes on a journey of self-discovery by traveling with his needy girlfriend (Karen Black) to his father’s house after learning he has fallen ill. Nicholson delivered one of his finest and most nuanced performances of his career in playing a disaffected and emotionless man frustrated with life’s responsibilities, earning himself his first Oscar nomination for Best Leading Actor. Most importantly, the film connected with a large audience, becoming a substantial hit and turning Nicholson into a star. He followed with “Carnal Knowledge” (1971), Mike Nichols’ sex comedy of errors about two lifelong friends (Nicholson and Art Garfunkel) and their romantic relationships over the course of a 25-year period that spans their college days in the 1940s to middle-adulthood in the early 1970s.

In between “Five Easy Pieces” and “Carnal Knowledge,” Nicholson directed his first film, “Drive, He Said” (1971), an examination of a sexually-promiscuous college basketball star (William Tepper) who likes to explore his prowess both on the court and in the bedroom; particularly the latter with his professor’s wife (Karen Black). Despite several fine performances, critics knocked his directorial debut for being dated and too confusing. Back to acting, a surprisingly introverted Nicholson starred in “The King of Marvin Gardens” (1972), playing a late-night radio talk show host in Philadelphia whose brother (Bruce Dern) calls out of the blue to inform him of his plan to open a Hawaiian resort, which ultimately leads to disillusionment and alienation. Nicholson then gave another sterling performance, this time playing “Badass” Buddusky in “The Last Detail” (1973), Hal Ashby’s darkly comic tale about Navy lifers (Nicholson and Otis Young) whose job transporting a military prisoner (Randy Quaid) turns into a week-long object lesson in fighting, drinking and getting laid. Nicholson’s raucous performance as the foul-mouthed Buddusky earned him a second Oscar nod for Best Leading Actor.

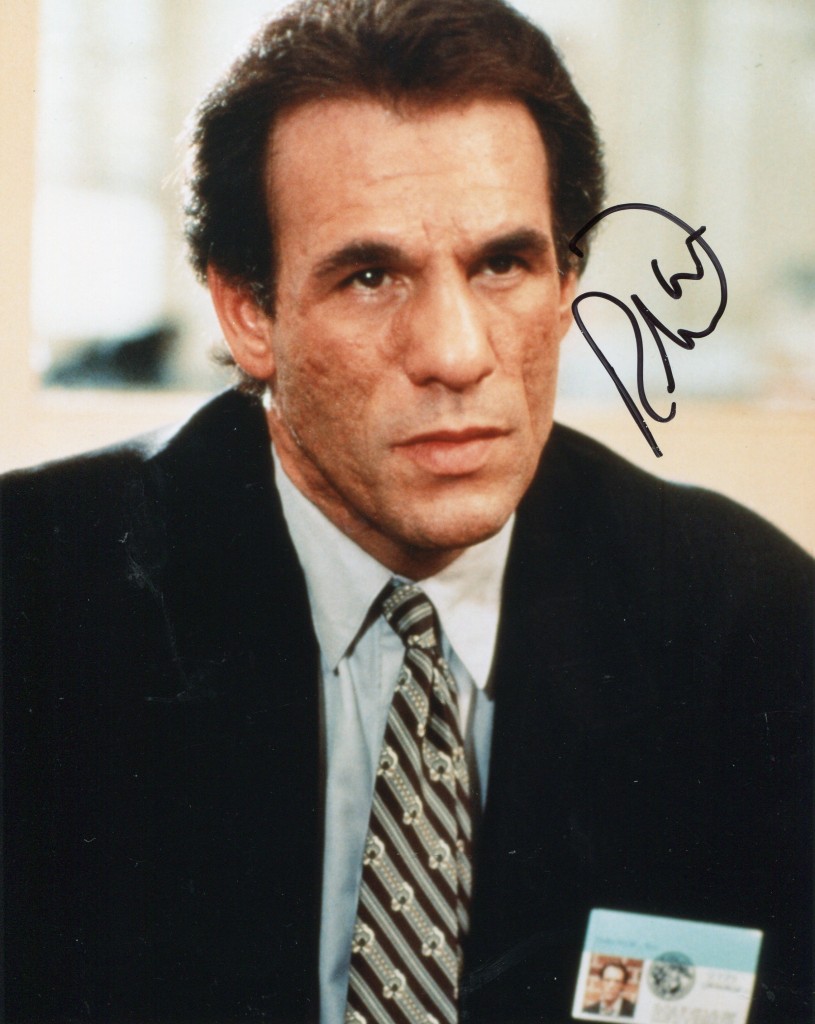

Perhaps no other role in Nicholson’s career was more revered or referenced than his portrayal of the Chandleresque gumshoe, Jake Gittes, in Roman Polanski’s ode to film noir, “Chinatown” (1974). In the director’s lush, cynical and serpentine story set in 1930s Los Angeles, Nicholson’s portrayal of a dogged private dick who hunts down the murderer of a water department official was a complex, deeply-nuanced turn that cemented the actor as one of Hollywood’s top actors. Nicholson’s Gittes is hired by a woman claiming to be the wife of the chief engineer with L.A.’s water department, who turns up dead in a water runoff pipe. When the real wife, Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway), suddenly shows up, however, Gittes is pulled into much darker and more sordid scandal that he could ever have imagined. Written for him by longtime friend Robert Towne, the Gittes character incorporated the collective Nicholson and elevated it to a fever pitch, allowing Polanski to use him as the straw to stir a very heady mix that also included director John Huston. The fact that Nicholson had recently begun seeing Huston’s daughter, Anjelica, added subtext menace when, as Noah Cross, Huston ominously slurred, “Are you sleeping with her?” A spicy combination of fact and fiction, “Chinatown” recalled the swindles and corruption that helped transform small town Los Angeles into a modern metropolis, while earning numerous awards and nominations, including another Best Actor nod for Nicholson at the Academy Awards.

Though not honored by the Academy for his portrayal of Gittes, Nicholson finally won an Oscar for starring in Milos Forman’s superb ensemble showcase, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975), based on author Ken Kesey’s acclaimed novel of the same name. Nicholson played R.P. McMurphy, an unruly convict sent to a mental institution, where his pranksterish antics endear him to a cadre of depressed patients while he also runs afoul with the authoritarian Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher). As an allegory for societal oppression upon man’s natural inclination towards freedom, “Cuckoo’s Nest” served as a sharp indictment of the Establishment’s unending need for conformity, with the rebellious McMurphy waging an ultimately futile battle, though he manages to pass on his message of escape to another prisoner (Will Sampson), assuring that his spirit will never die. Earlier that year, Nicholson starred in Michelangelo Antonioni’s “The Passenger” (1975), the actor’s only European movie, in which he played an alienated journalist in North Africa who – while desiring another life – assumes the identity of a dead man he stumbles upon, only find himself embroiled in gun-running on behalf of a terrorist group.

As the 1970s began winding down, Nicholson began abandoning his more subtle shadings for over-the top ham-handedness and occasionally even self-parody. But buried beneath such excesses, one always found signs of what had made him a great actor. He teamed with Marlon Brando – also at the time suffering from the same malady – for the disastrous “Missouri Breaks” (1976), an eclectic Western that veered from broad comedy one minute and unrelenting violence in the next, creating an uneven and ultimately convoluted take on a steadfast genre. Then in 1977, the actor’s name was dragged through the mud when friend and collaborator Roman Polanski was arrested for statutory rape of a 13-year-old girl, which occurred at Nicholson’s Mulholland Drive home. But like any other negative press that came his way, Nicholson was able to avoid any permanent scars. Meanwhile, after playing a horse thief saved from the noose by marrying a frontierswoman (Mary Steenburgen) in “Goin’ South” (1978), Nicholson returned to form in “The Shining” (1980), Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of Stephen King’s famed horror novel. As the rapidly diminishing Jack Torrence, an unsuccessful writer who takes on the job of caretaker at the remote Overlook Hotel with his wife (Shelley Duvall) and son (Danny Lloyd), Nicholson delivered one of his more over-the-top performances as a man whose isolation and frustrations descend into violence. Though no awards were forthcoming, Nicholson was nonetheless memorable in a role that spawned the infamous line, “Here’s Johnny!”

Nicholson entered the 1980s a different actor than the one who emerged onto the scene with subtle, nuanced performances like he gave in “Five Easy Pieces” and “Easy Rider.” In its place was a new Nicholson who enjoyed mugging for the camera with arched eyebrows, as he did playing a simpleminded and selfish murderer in Bob Rafelson’s disappointing noir “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (1981). He did, however, craft a fine portrayal as the cynically romantic playwright Eugene O’Neill in “Reds” (1981), actor-director Warren Beatty’s landmark epic about the true-to-life romance between journalist and revolutionary Jack Reed (Beatty) and writer-artist Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton), set against the backdrop of World War I and the Russian Revolution. Nicholson delivered his finest – and most underappreciated – performances of the decade, earning another Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor. After playing a border guard who accepts payoffs to allow illegal immigrants to cross from Mexico in “The Border” (1982), Nicholson was a boisterous and boozy ex-astronaut who doggedly pursues his widowed neighbor (Shirley MacLaine) in “Terms of Endearment” (1983). Eschewing bombastic theatrics, Nicholson once again delivered the kind of performance that had catapulted him to stardom, earning him his second Oscar as Best Supporting Actor.

Nicholson’s win for “Terms of Endearment” was a high-water mark in a string of Academy Award nominations he received in the 1980s – in fact, it was his only win of the decade in four tries. He was nominated again for Best Actor when he played a not-so-honorable Mafia hit man in “Prizzi’s Honor” (1985), one of director John Huston’s final films. Following a not very memorable leading turn in the Mike Nichols romantic comedy, “Heartburn” (1986), Nicholson found himself in the Oscar running once again for his performances as a washed-up baseball player wallowing in misery and alcohol in the acclaimed period drama, “Ironweed” (1987). In “The Witches of Eastwick” (1987), Nicholson delivered one of his more deliriously over-the-top performances playing the mysterious Darrell Van Horn, who uses his strange allure to seduce three female friends (Cher, Michelle Pfeiffer and Susan Sarandon). His frenzied theatrics were put to good use as The Joker in Tim Burton’s version of “Batman” (1990). Nicholson’s lighter take on the Joker dominated the film, which served as the perfect backdrop for his perpetually posturing and leering psychotic villain always fond of a dark, twisted joke.

After 16 years since the release of “Chinatown,” Nicholson stepped behind the camera for a third time to direct “The Two Jakes” (1990), the sequel to the first film that depicted a more subdued and beaten-down Jake Gittes who becomes involved in a murder and conspiracy scheme stemming from a real estate deal that was part of the original film’s story. Nicholson and writer Robert Towne attempted a sequel in the mid-1980s, but failed to get the project off the ground. When they finally did, the long friendship shared between the two collaborators suffered, causing irreparable harm. Prior to filming “The Two Jakes,” Nicholson subverted his relationship with Anjelica Huston when she discovered that he had impregnated actress and model Rebecca Broussard, ending what ultimately proved to be the actor’s longest romantic entanglement. Back to acting, Nicholson was in top form as the commanding officer covering up a murder on his Cuban military base in Rob Reiner’s “A Few Good Men” (1992). Nicholson’s famed line, “You can’t handle the truth!” helped him earn yet another Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor. Despite a valiant effort, Nicholson failed to save Danny De Vito’s unnecessarily convoluted biopic, “Hoffa” (1992), which traced the rise and mysterious fall of the controversial founder of the Teamsters Union.

Nicholson’s next turn, playing a book editor who gradually evolves into a werewolf in Mike Nichols’ “Wolf” (1994), served as a metaphor for confronting mid-life crises. At the start of the film, before the wolf bites him, he is weak-willed and passive, but his transformation into the wolfman brings virility and growing confidence. Not surprisingly, Nicholson called into play many of his trademark mannerisms, offering a wry, sly commentary on his star power, proving once again there was no limit to how long he could get away with such hokum. Meanwhile, he made further headlines that year when he was involved in a road rage incident in which he allegedly smashed another driver’s windshield with a golf club. Once again, he averted public embarrassment by quietly reconciling the situation. Then in Sean Penn’s “The Crossing Guard” (1995), Nicholson once again essayed a bitter man confronting the wounds of the past. As a jeweler whose daughter has been killed by a hit-and-run driver, he delivered a nuanced portrait that was equal parts guilt and grief, while the scenes shared with real-life former lover Anjelica Huston – who played his ex-wife – mined an understandably rich vein of remembered feeling.

In 1996, Nicholson found himself reprising his Oscar-winning turn as Garrett Breedlove opposite Shirley MacLaine in “Evening Star,” then played the dual role of the U.S. President and a sleazy Las Vegas promoter in Tim Burton’s “Mars Attacks!” (1996), an ode to 1950s sci-fi flicks that delivered cheesy comedy perfect for the broad strokes of the vaunted Nicholson caricature. Meanwhile, he reunited again with Bob Rafelson for the competent thriller “Blood and Wine” (1997), which proved to be compelling to the few people that actually saw the film. Nicholson then reunited with James L. Brooks in an Oscar-winning turn as a curmudgeonly, obsessive compulsive and homophobic author who falls for a single mother (Helen Hunt) struggling to make ends meet as a waitress, while eventually developing a grudging friendship with his gay neighbor (Greg Kinnear) in the richly appealing dramatic comedy, “As Good as It Gets” (1997). For his undeniably sharp performance, Nicholson earned the third Academy Award of his career.

After a three year hiatus, Nicholson returned to the big screen as Jerry Black in the thriller feature “The Pledge” (2001), another harrowing directorial effort from his friend Sean Penn, in which Nicholson delivered a performance that was widely hailed by critics in an otherwise bleak film. In 2002, Nicholson made another comeback, teaming with writer-director Alexander Payne for “About Schmidt,” an introspective, serio-comic about Warren Schmidt, an unhappy and retired salesman reflecting on his life, making a cross country trek to attend the wedding of his estranged daughter after the sudden death of his wife. His fresh, unexpected and surprisingly understated performance was rewarded with several award nominations and trophies, including the Golden Globe for Best Actor in a Motion Picture Drama and an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor, the twelfth nomination of his career, breaking his own record as the most nominated male actor in Oscar history.

Balancing his penchant for top-level acting with a bid for another major commercial success, Nicholson next teamed with popular comedy star Adam Sandler for “Anger Management” (2003), with both stars contributing to the screenplay. Taking his charismatic devilishness into uncharted territory, Nicholson played an unconventional anger management therapist who exacerbates – rather than cures – the rage of his patient (Sandler). The actor then took on another late-career-defining role when he starred opposite Diane Keaton in the romantic comedy “Something’s Got to Give” (2003), playing an aging womanizer with a penchant for much-younger women who surprises himself by taking up with the mother (Keaton) of one of his beautiful dates (Amanda Peet) following a heart attack in her beach house. Although the film was uneven in the early and late stretches, at the heart of the story Nicholson and Keaton displayed a remarkable romantic chemistry buoyed by comedic frisson, making for a crowd-pleasing hit that earned the actor yet another Golden Globe nomination for Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture Musical or Comedy.

After another brief hiatus from the big screen, Nicholson returned to join an all-star cast that included Leonardo DiCaprio, Matt Damon and Mark Wahlberg for “The Departed” (2006), a slick cop thriller directed by Martin Scorsese – marking the first collaboration of the two legends – and loosely based on the excellent Hong Kong actioner “Infernal Affairs” (2002). Nicholson played the nefarious and sexually deviant Frank Costello, a mob boss whose syndicate is infiltrated by an undercover cop (Leonardo DiCaprio). But Costello has his own mole (Matt Damon) inside the South Boston police department, pitting the two institutions against each other in a cat-and-mouse game that seeks to undermine the other’s operations while the two moles fight to expose each other. Nicholson then starred opposite Morgan Freeman in “The Bucket List” (2007), a comedy directed by Rob Reiner about two terminally ill men who break out of the hospital’s cancer ward and go on a road trip to fulfill their wishes before they kick the bucket. Despite mixed reviews, the film proved itself to be an exceptional winner at the box office.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online

here.

.