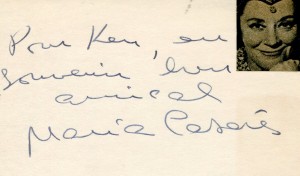

Unlike her seniors Edwige Feuillere and Madeleine Renaud, she brought an atavistic and foreboding sense of tragic destiny to her performances that made her unsuitable for comedy and the lighter theatre. She carried on the tradition of Sarah Bernhardt in performing the great roles of Greek tragedy and of the French classical theatre, Phedre being one of her most outstanding performances, but she also played a multiplicity of parts in plays by Ibsen and early moderns and by contemporary playwrights including Brecht, Genet, Anouilh, Sartre, Camus, Claudel and Edward Bond among others. She introduced J.M. Synge to the French public with a legendary production of Deirdre of the Sorrows in 1942 under the German occupation and shortly afterwards made her screen debut as Dubureau’s wife Nathalie in Marcel Carne’s great film Les Enfants du Paradis (1943). She was 21 at the time.

Although she made many films and her electrifying presence, with its dark beauty, innate smouldering passion and controlled violence – and most unforgettably of all her expressive eyes – made her an instant star, ideally suited to the cinema, she was happier and more at home in the theatre. No one could portray evil, especially evil destiny, better than she – Medea and Lady Macbeth were only two of the parts that gave her such opportunities – but she is well remembered, and still can be seen, in Jean Cocteau’s classic films, Orphee (1949) and Le Testament d’Orphee (1959), where she played Death.

The timeless quality of her mythological roles was unique. She was an actress of great intelligence and her autobiography, Residente privilegiee (referring to the words on her French identity card), published in 1980, testifies to her intellectual breadth, political commitment and literary skill. Like Proust she was able to bring her past, especially her early Spanish experiences, into the present, through an association of objects, places, people and allusions, so that her book is a series of fragments linked by memory.

Her knowledge and sense of history helped her to understand the events and motivations that lay behind so many of the roles she played, and she became a real avatar of her characters on stage and screen. During the Spanish Civil War she had been, at the age of 14, a voluntary nurse in Madrid hospitals, working to exhaustion tending the wounded, aware of real tragedy hourly before her eyes, and of the particularly Spanish stoic courage and mordant humour displayed by the suffering and dying Republican defendants of the city. Her father, Santiago Casares Quiroga, was a member of the Republican government, and in 1936 he and the whole family just managed to flee to France before the border was closed.

The next six years were difficult for the family, staying in cheap hotels with little money, but Maria Casares learned French and on her 20th birthday, in the Theatre des Mathurins, she opened in Deirdre of the Sorrows, her first part, to immediate fame; and thereafter never looked back.

Her incredible eyes, that could express anger, scorn, hatred or the menace of eternity, but also love and incandescent passion, her noble bearing, which made her so suitable for the great female dramatic parts, and her deep expressive voice attracted all the major playwrights of the day, and she was in constant demand both for modern plays and by the great state-funded drama companies, the Comedie-Francaise and Jean Vilar’s Theatre National Populaire (TNP), to play the classics. She was with the former company from 1952 to 1954, and opened the first seasons of the Avignon Festival with Vilar, which introduced her to many Shakespeare parts.

She subsequently joined the TNP where she starred with Gerard Philipe in Le Cid and in many other plays, touring America and Europe as well as playing in Paris. She appeared many times with the Renaud-Barrault company in their seasons at the Odeon and during Jean-Louis Barrault’s later odyssies in improvised theatrical spaces, after de Gaulle removed the subsidy in 1968.

Maria Casares was a private person who liked to return to her house in the country to prepare her parts, think and read. She married another actor, “Dade” Schlesser, in 1978, with whom she had played together on the stage for many years, especially at the TNP, where he was only junior to Vilar; he was an Alsatian of gypsy origin. His sardonic sense of humour – during the war he was imprisoned for five days for saying to a German officer with a straight face that he had never heard of Adolf Hitler – and philosophical bent, exactly matched her own, and he became the companion of her later years. She was on the stage until only a few months before her death.

John Calder

Maria Casares, actress: born La Coruna, Spain 21 November 1922; married 1978 Dade Schlesser; died Paris 22 November 1996.