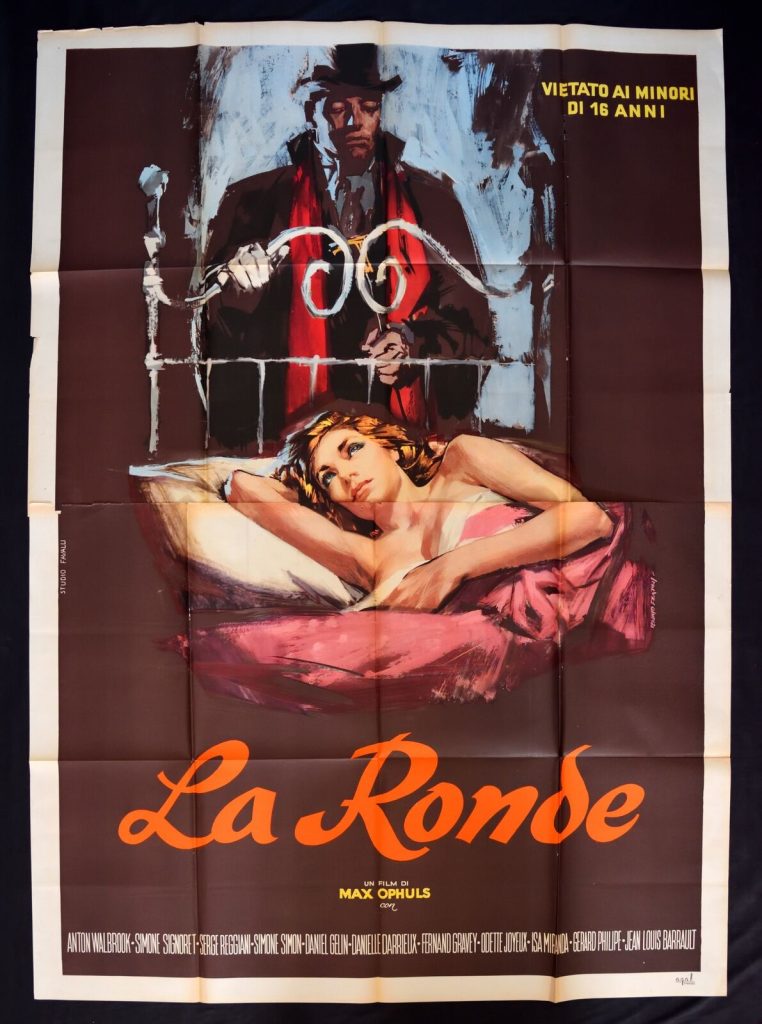

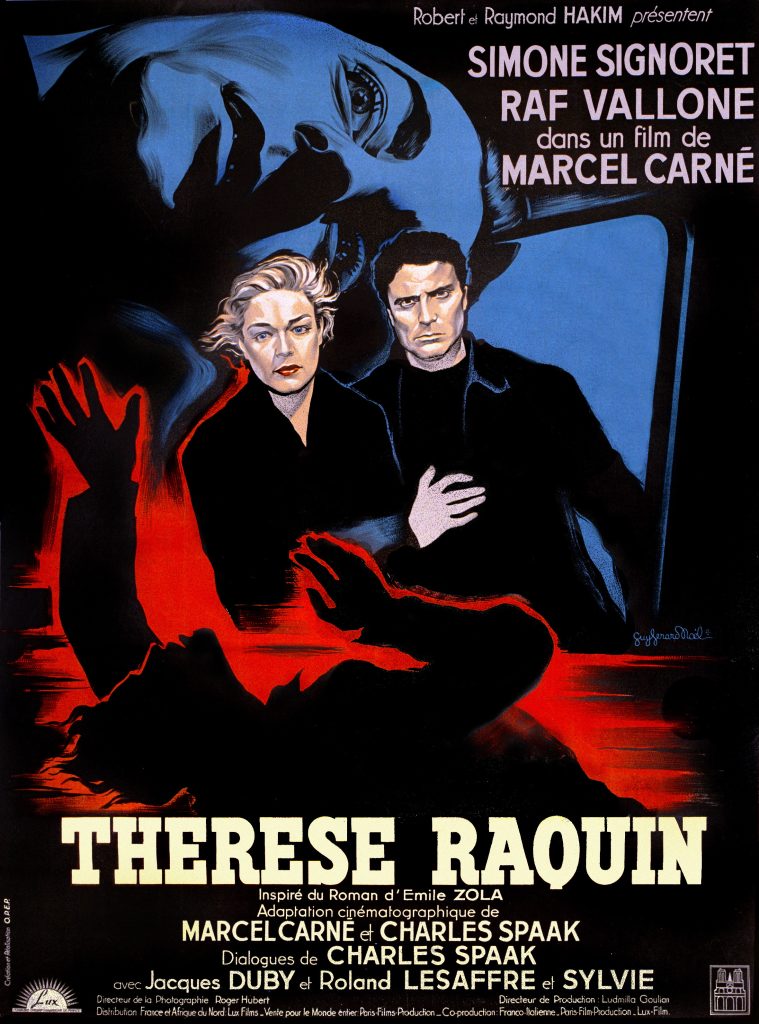

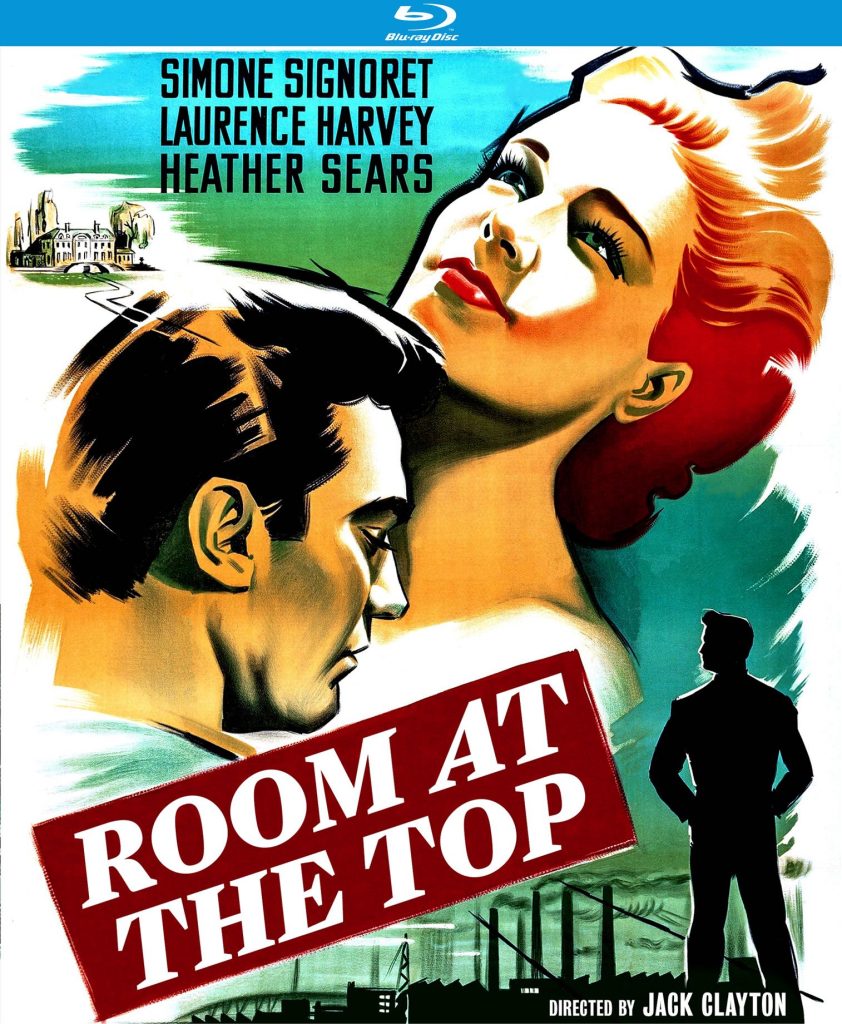

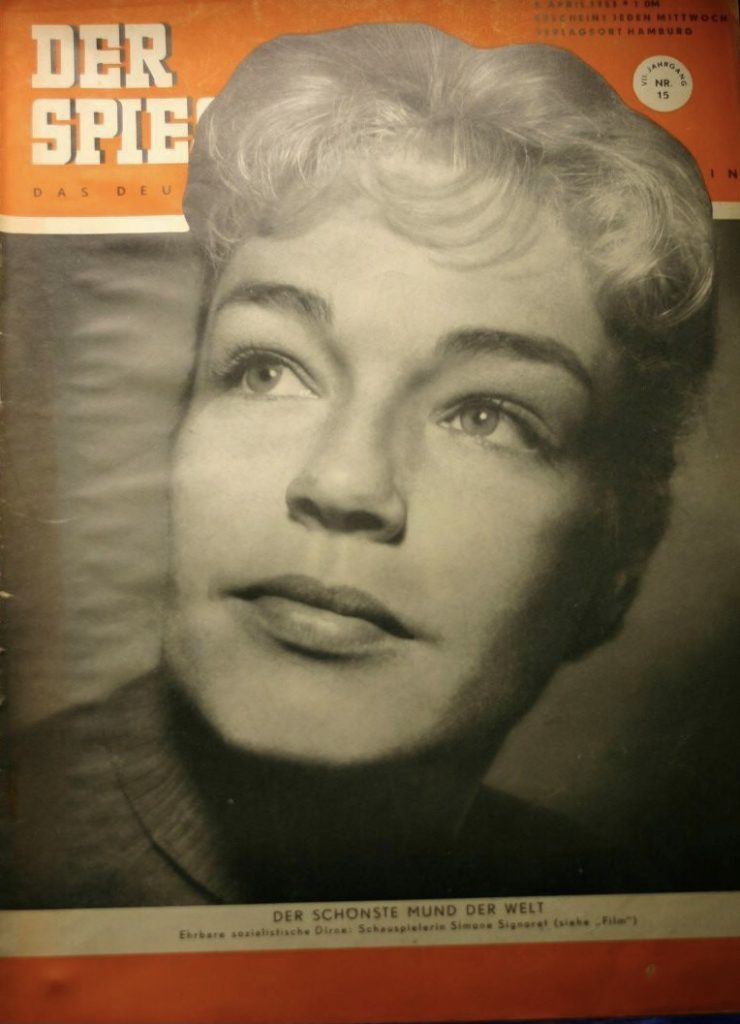

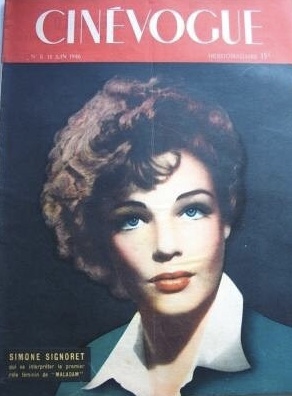

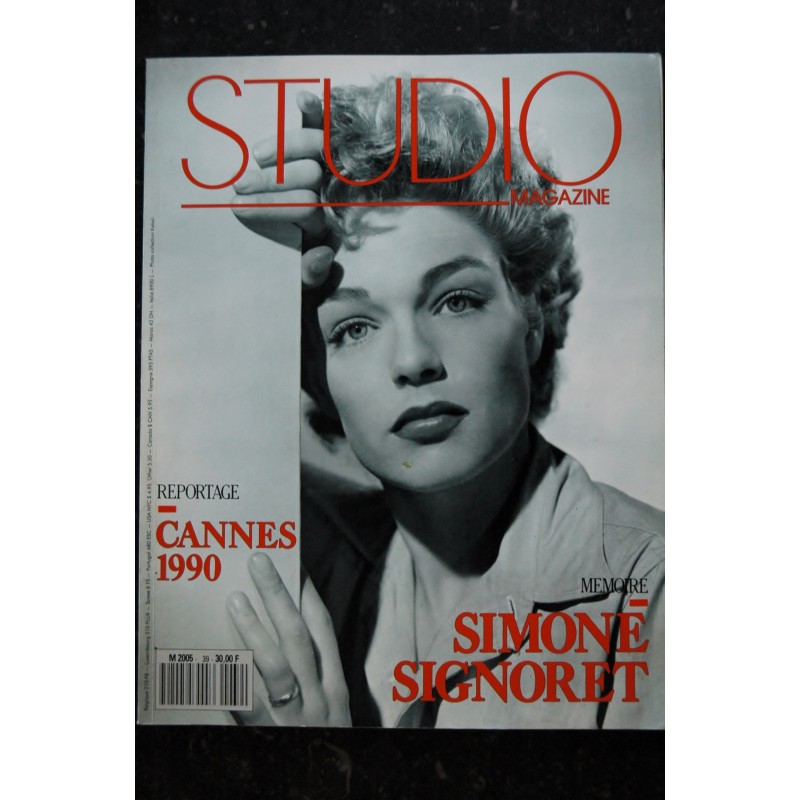

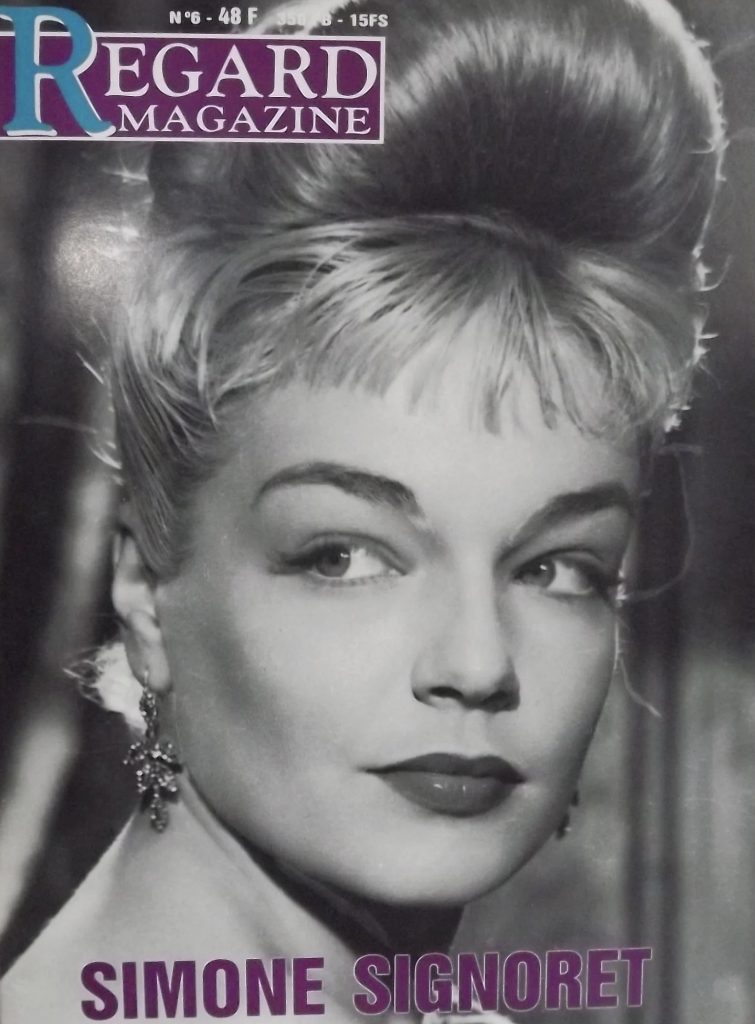

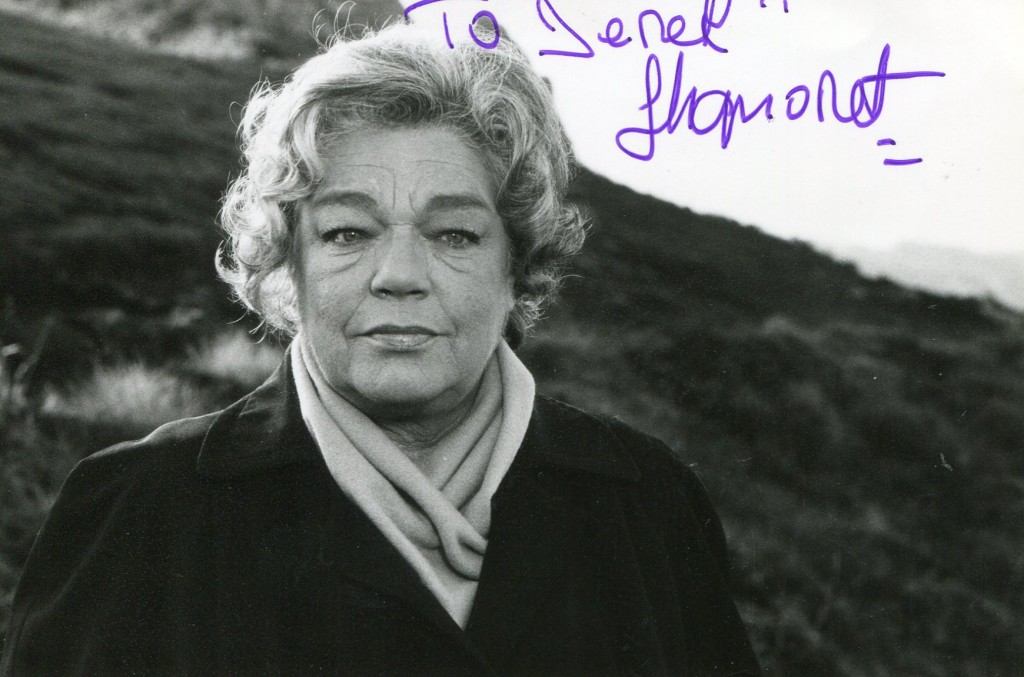

Simone Signoret was one of France’s greatest movie actors and the first French person to win an Oscar for acting – “Room At The Top” in 1959. She was born in Germany but moved to France as a child. Her major French movies include “La Ronde” and “Therese Requin” in 1953 and “Les Diaboliques”. In 1964 she went to Hollywood to make “Ship of Fools” with Oskar Werner, Vivien Leigh and Lee Marvin. Her husband was Yves Montand. She died in 1985.

TCM overview:

An iconic figure in the history of 20th century French cinema, Simone Signoret was an Oscar-winning actress whose sensuous and sensitive performances in such films as “Casque d’Or” (1952), “Les Diaboliques” (1955), “Room at the Top” (1957) and “Ship of Fools” (1965) drew critical acclaim for nearly four decades. She began in bit parts during the 1940s, eventually working her way up to supporting turns as tragic seductresses in “Dédée d’Anvers” (1948), among others. By the 1950s, she was showing exceptional depth in a wide variety of arthouse classics, including “Diaboliques,” an enduring chiller that solidified her screen persona as a complex, even dangerous woman. In 1957, she became the first foreign actress to win an Academy Award for her turn as an unhappy wife in “Room at the Top,” but surprised many by favoring continental productions over Hollywood. The decision was a shrewd one, as it gave her some of her best features, including “Army of Shadows” (1969), “Le Chat” (1971) and “Madame Rosa” (1977). A childhood spent under the shadow of Nazi Germany made her a dedicated supporter of human rights throughout her life, which culminated in the 1985 documentary “Terrorists in Retirement,” about Eastern European Jews who fought in the French Resistance. It would be her final grand accomplishment before her death that year from cancer. Critics and audiences around the world mourned the passing of an actress whose bravery, honesty and commitment to cinema remained of the highest order.

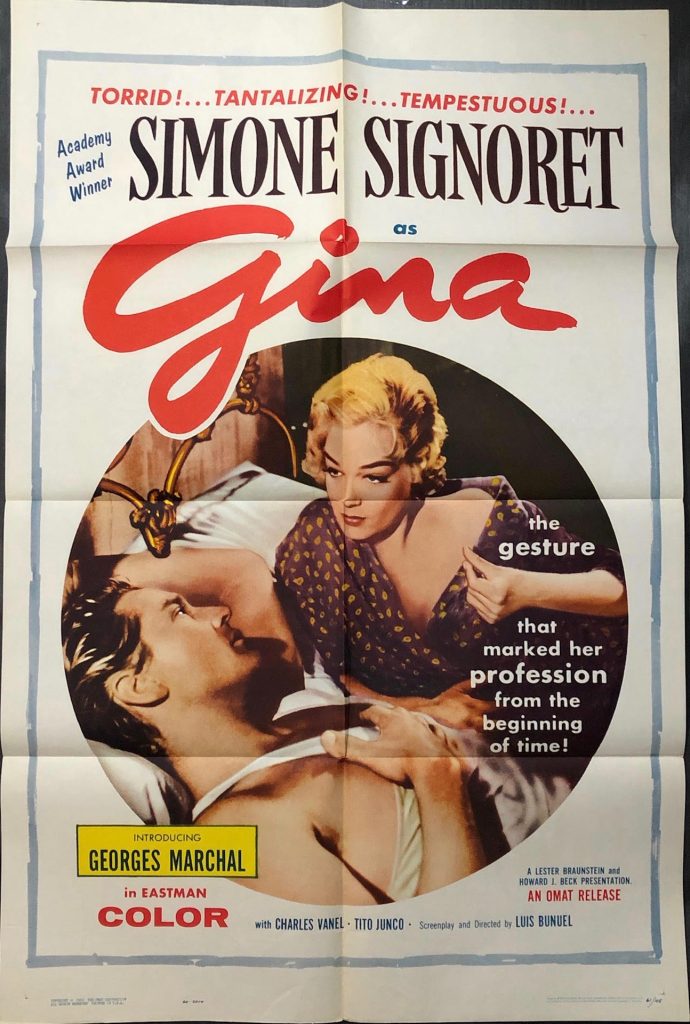

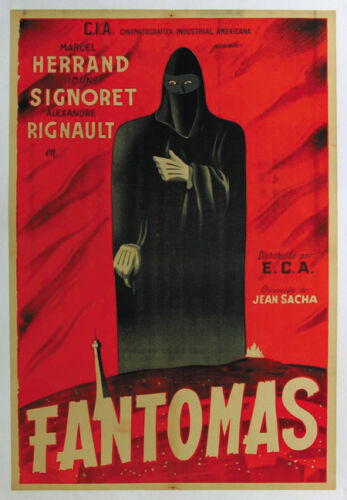

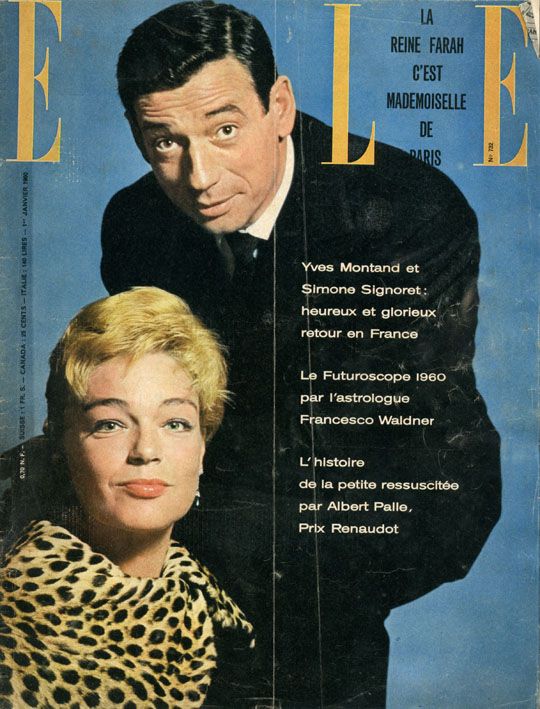

Born Simone Henriette Charlotte Kaminker in Wiesbaden, Germany on March 25, 1921, she was the eldest of three children by André Kaminker, an Army officer and linguist, and his wife, Georgette Signoret. The family later moved to the Parisian suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine, where Signoret learned and eventually taught English. As a young woman, she moved with an intellectual, politically informed crowd at the Café de Flore in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés quarter that would have a profound influence on her own commitments to political and social causes. The German occupation of France in 1940 forced Signoret’s father, a Polish-Austrian Jew, to flee the country and join General Charles de Gaulle’s opposition in England. In need of a means to provide for her mother and younger brothers, Signoret began working as a movie extra. Billed with her mother’s maiden name to avoid Nazi scrutiny, she worked steadily in bit roles that frequently hinged on her earthy sensuality – dancers, call girls and the like. In 1944, she caught the attention of director Yves Allegrét, who cast her in her breakout film, “Dédée d’Anvers” (1948) as a prostitute in love with a young Italian soldier. He also became her first husband and father of her only child, future actress Catherine Allegrét. Their union would run its course by the release of their second screen collaboration, “Manèges” (“The Cheat”) (1950), but by then, Signoret had become a star in her own right. She had also forged what would become her most enduring personal relationship with actor Yves Montand, who became her second husband in 1950, as well as her most devoted supporter.

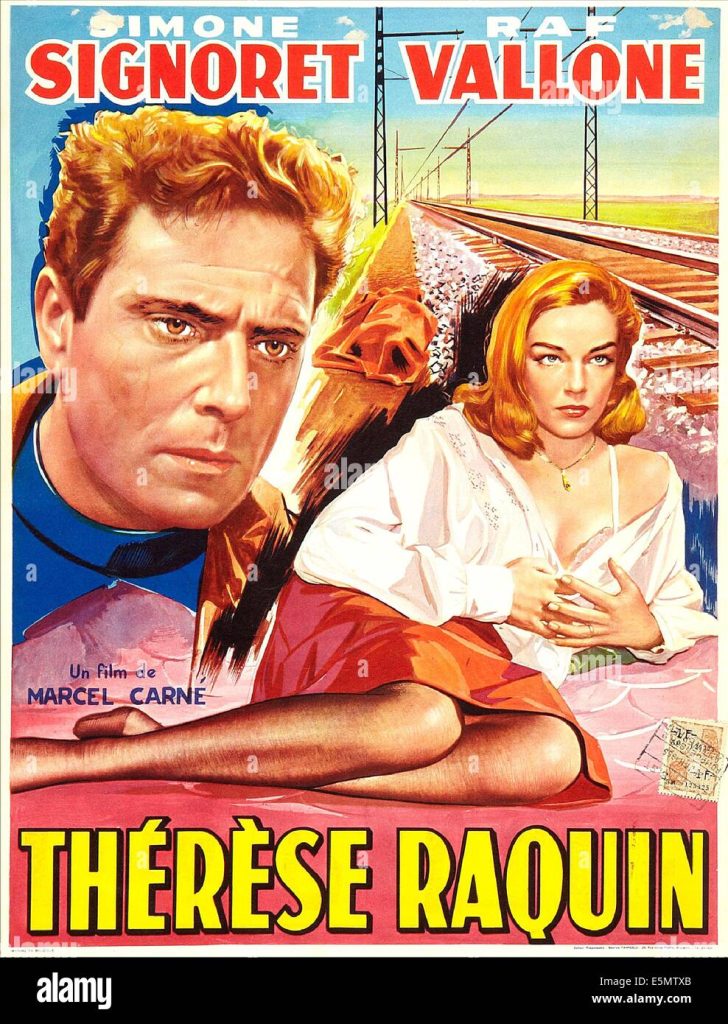

The 1950s were the high point of Signoret’s career and personal life, but also one of her most turbulent decades. She became one of France’s most acclaimed actresses with a series of acclaimed portrayals of women in the grip of turbulent love affairs; in Jacques Becker’s “Casque d’Or” (1952), her underworld moll unwittingly launched a chain of violence in her attempt to seek a loving relationship, while Marcel Carné’s “Thérèse Raquin” (“The Adulteress”) (1953) put her at the center of a love triangle with a thoughtless husband (Jacques Duby) and a handsome truck driver (Raf Vallone). Her most enduring film from this period was undoubtedly “Les Diaboliques” (“Diabolique”) (1955), a harrowing thriller from Henri-Georges Clouzot, with Signoret and Vera Clouzot as the mistress and wife, respectively, of a cruel schoolmaster who became the target of their complex murder scheme. The film’s success established Signoret as one of France’s biggest stars, and she parlayed her fame into drawing attention to various political causes.

With Montand by her side, she openly voiced her opposition to Russia’s involvement in Hungary, the U.S. in Vietnam, and her own country in Algiers. She was also vehemently opposed to the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on espionage charges in 1953, which spurred her and Montand to star in a French-West German film version of “The Crucible” (1957). For a period, her allegiances prevented her from gaining a visa into the United States, but she and Montand would eventually visit the play’s author, Arthur Miller, in America prior to making the film, during which time Montand had a well-publicized affair with the playwright’s then-wife, Marilyn Monroe. With typical European aplomb, she dismissed the incident, stating that she found no fault in Monroe’s infidelity, as it confirmed Signoret’s own good taste in lovers.

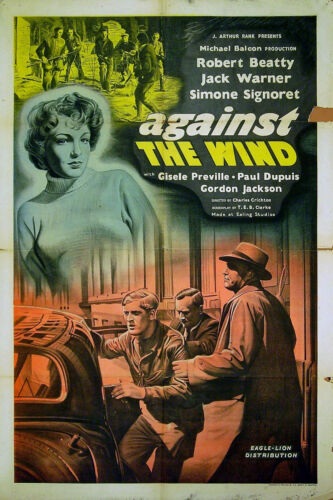

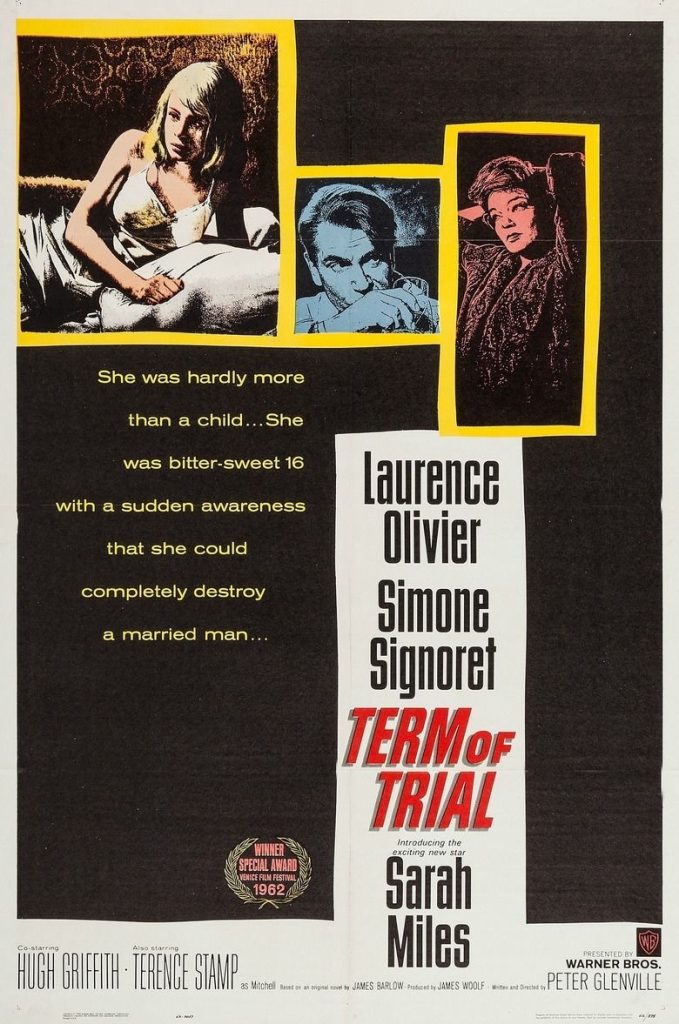

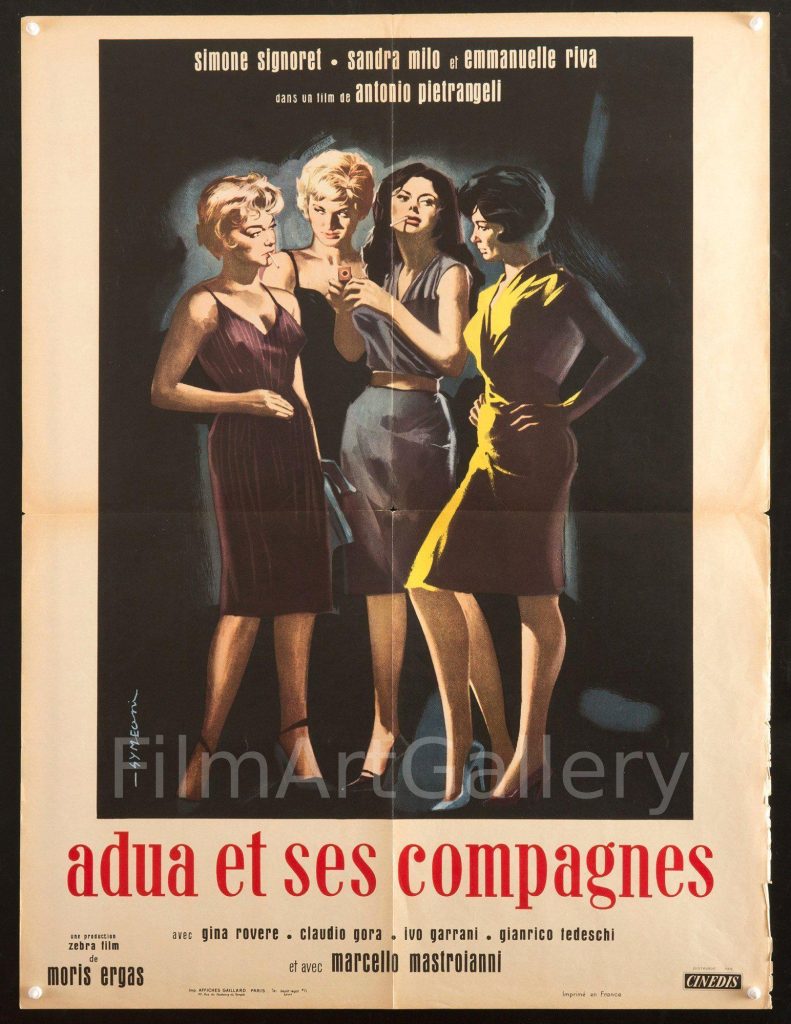

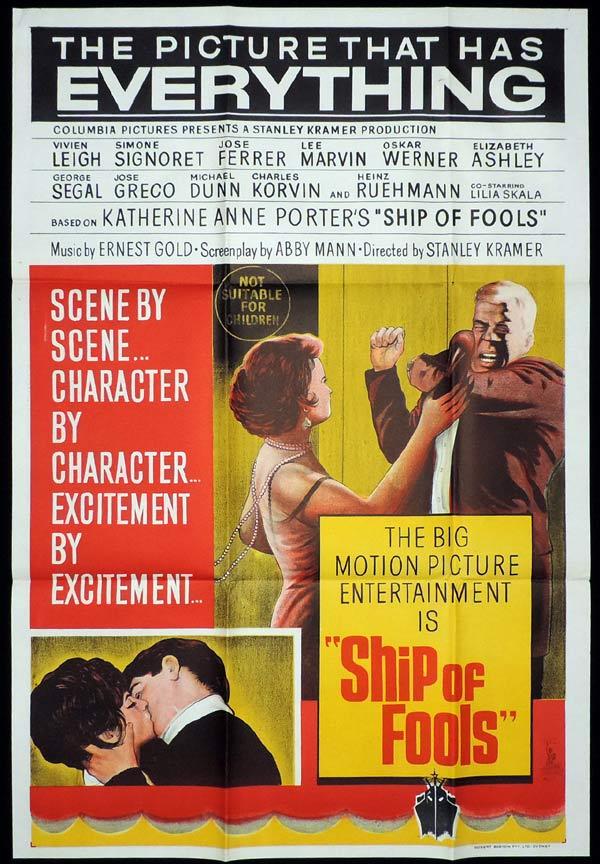

Signoret won the BAFTA for her turn in “The Crucible,” but surpassed that accomplishment two years later with her powerful performance in “Room at the Top” (1959). Cast as an unhappily married older woman who entered into a doomed affair with amoral social climber Laurence Harvey, Signoret claimed not only a second BAFTA but also the Oscar and Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Actress, among other laurels. The wins led to offers of work in Hollywood, but Signoret turned them down, preferring instead to remain a key figure in European films. She worked steadily throughout the 1960s, earning acclaim for turns as the neglected wife of an unfaithful teacher (Laurence Olivier) in “Term of Trial” (1962) and as a suspect in a “perfect murder” case in Costa Gavras’ “The Sleeping Car Murders” (1965) that also featured Montand and her daughter. Signoret earned an Oscar nomination as a drug-addled countess on an ocean liner bound for Nazi Germany in Stanley Kramer’s “Ship of Fools” (1965). The following year, she won an Emmy for “A Small Rebellion,” a 1966 teleplay on “Bob Hope Presents The Chrysler Theatre” (NBC, 1963-67).

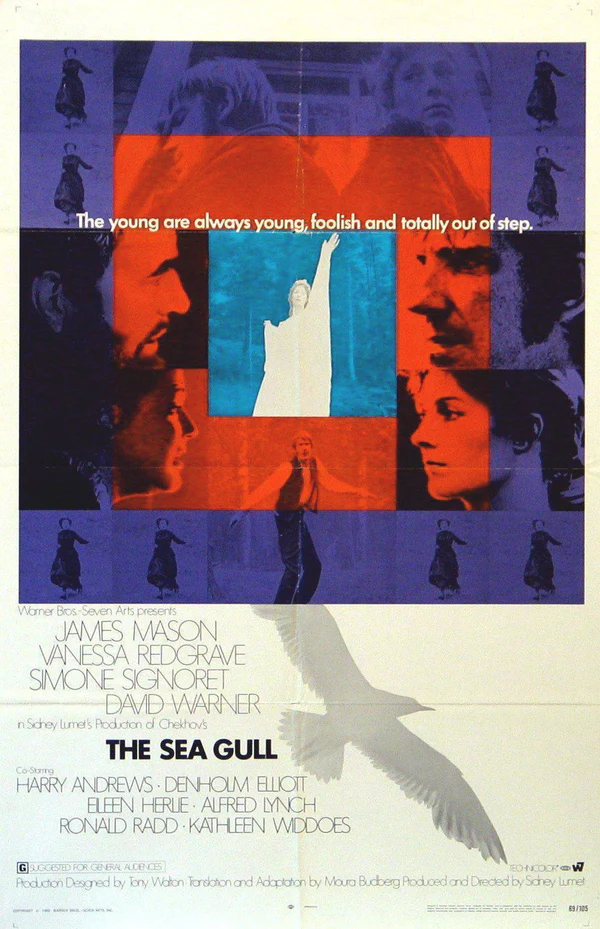

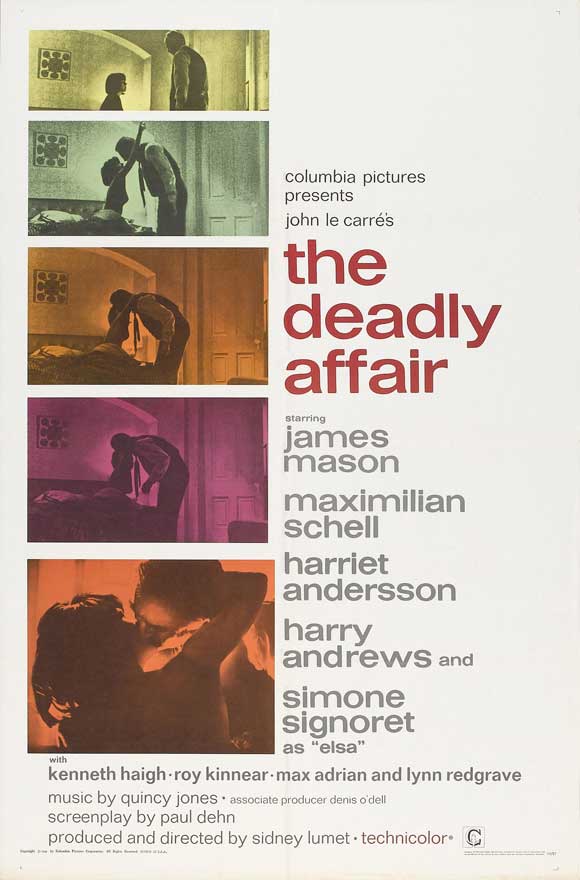

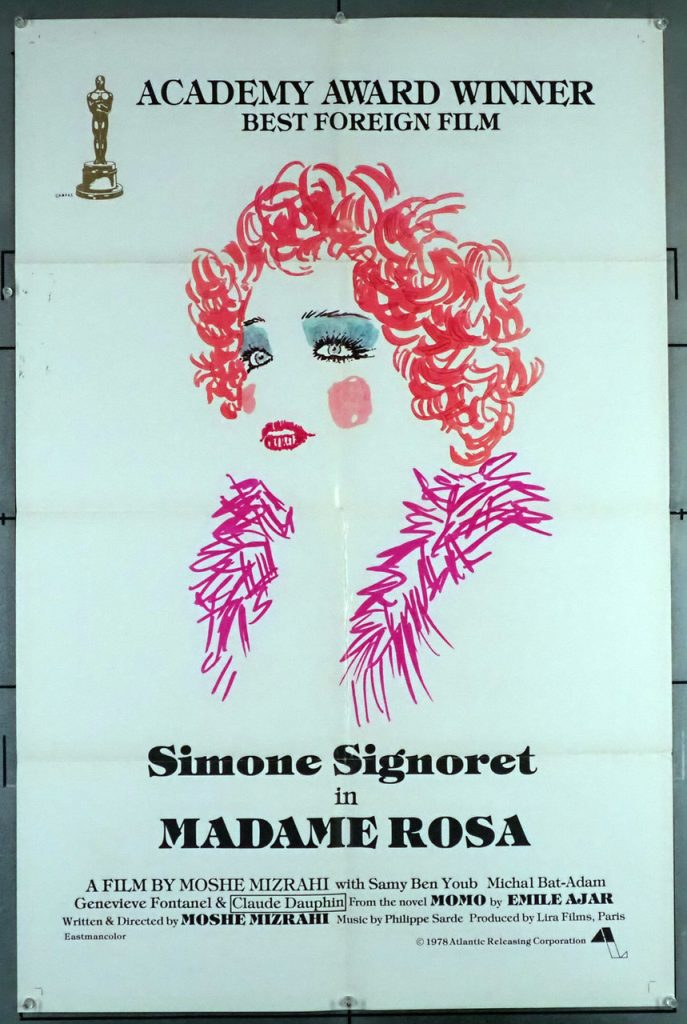

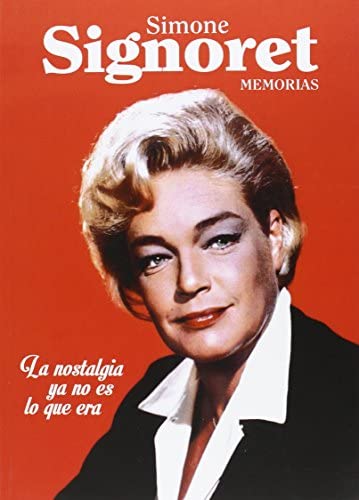

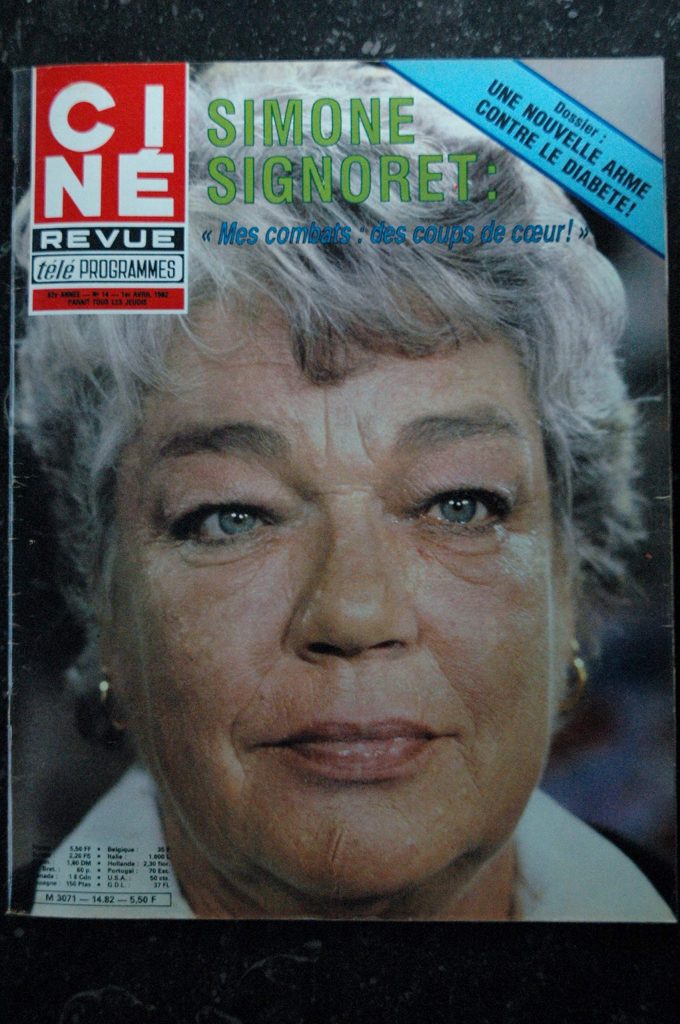

In the late 1960s, Signoret managed to avoid the pitfalls that awaited many actresses as they entered their late forties. She was no longer playing seductive wantons, but the breadth of her talent allowed her to segue into supporting roles and occasional leads with considerable substance. She received back-to-back BAFTA nominations for Sidney Lumet’s “The Deadly Affair” (1967) and Curtis Harrington’s cult favorite “Games” (1967) as, respectively, a concentration camp survivor with ties to a government official’s suicide and a mysterious woman who disrupted the lives of callous socialites James Caan and Katharine Ross. Haughty critics derided her decision to allow herself to age naturally, but the added years brought gravitas to her later roles, including a French Resistance collaborator in Jean-Pierre Melville’s “Army of Shadows” (1969) and an aging wife driven to jealousy by her husband’s (Jean Gabin) adoration of a stray cat in “Le Chat” (1971). The latter earned her a Silver Bear for Best Actress from the Berlin International Film Festival, while “Madame Rosa” (1977) brought her both the Cesar and David di Donatello Awards for her touching performance as an aging madam who forged a maternal relationship with a young Arab orphan. The following year, she published her memoirs, Nostalgia Isn’t What It Used to Be (1978) to considerable acclaim.

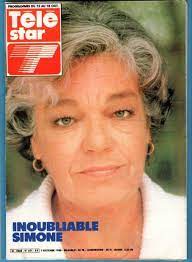

Signoret worked steadily in the final decade of her life, earning top billing in Jeanne Moreau’s “The Adolescent” (1979) as a grandmother who provided wisdom and guidance for her love struck granddaughter. The year 1985 saw the completion of “Terrorists in Retirement,” a documentary by Mosco Boucault about Eastern European Jews who aided the Resistance movement during World War II but received no credit for their heroism. Signoret and Montand had supported the film during its lengthy production history, but it remained banned from French television until after Signoret’s death. That same year, Signoret made her debut as a novelist with Adieu Volodia, about Jewish immigrants working in the Paris theatre between the late ’20s and the mid-’40s. The overwhelmingly positive response to the book signaled the beginning of a new phase in Signoret’s career. Sadly, she succumbed to pancreatic cancer on September 30 of that year, bringing to a close a remarkable, well-lived life.

By Paul Gaita