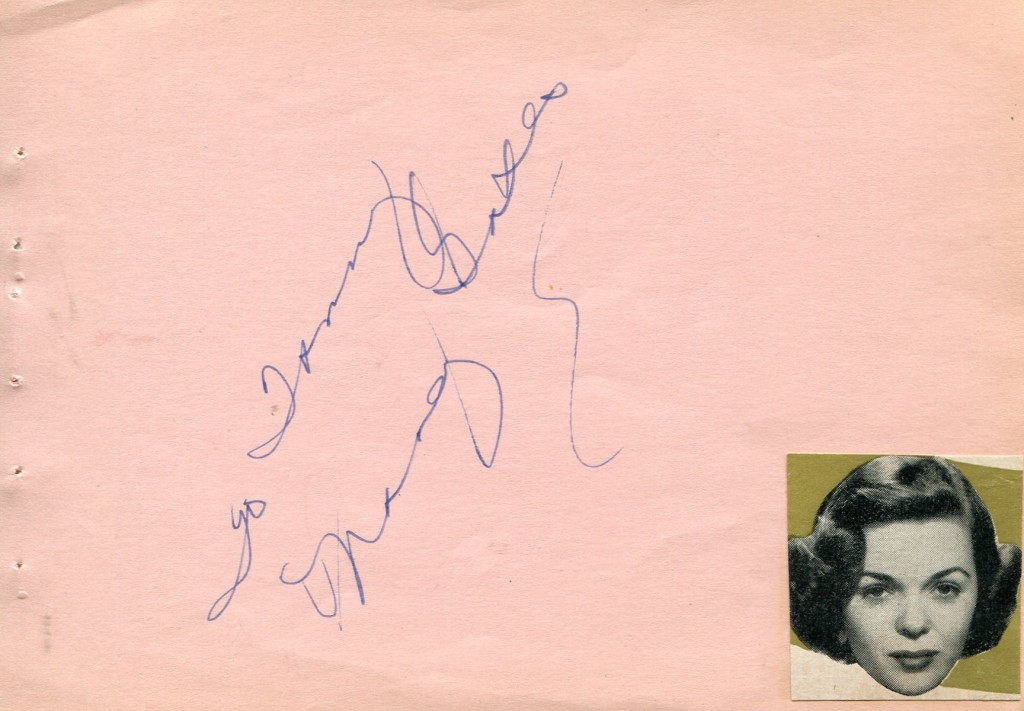

“Wikipedia” entry:

The daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Virgil Gates,[2] Nancy Gates was born in Dallas, Texas, Gates grew up in nearby Denton, and was described as “a child wonder.”A 1932 newspaper article about an Easter program at Robert E. Lee School noted, “Nancy Gates, presenting a soft-shoe number, will open the style show.” That same year, she had a part in the Denton Kiddie Revue.

In 1935,[6] she appeared in the production “A Kiss for Cinderella,” which starred Brenda Marshall and a minstrel show that included Ann Sheridan, both of whom were from Denton. She was in show business before she finished high school, having her own radio program on WFAA in Dallas[ for two years while she was a student at Denton High School,[ from which she graduated. Musically oriented, Gates was featured as a singer in a 1942 concert by the North Texas Teachers College stage band.

Gates attended the University of Oklahoma for one year before getting married.

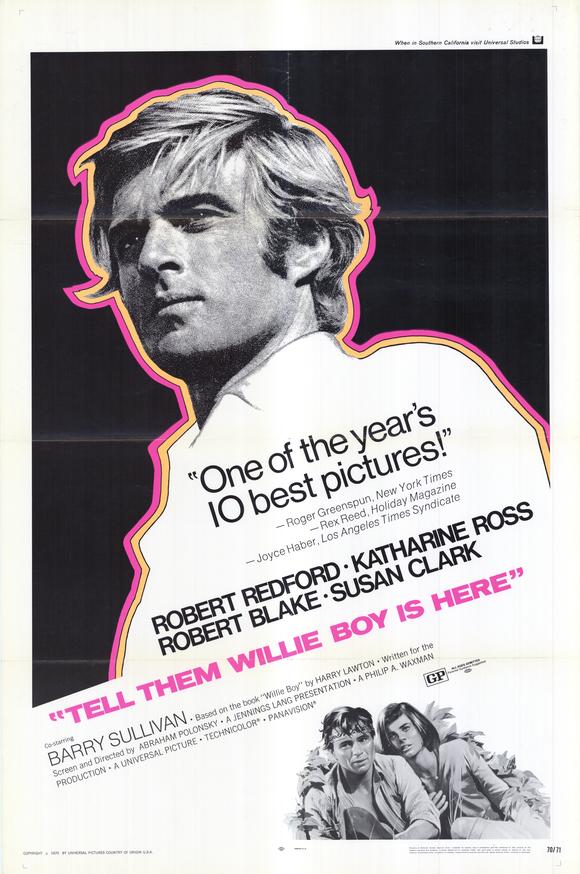

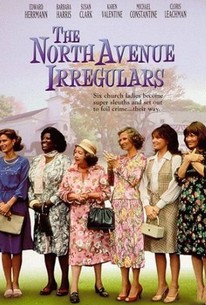

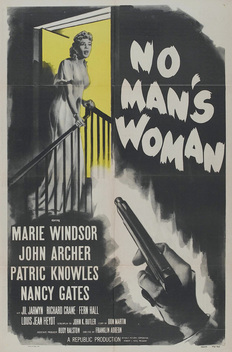

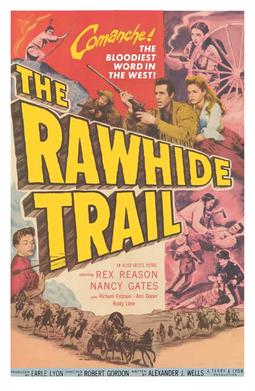

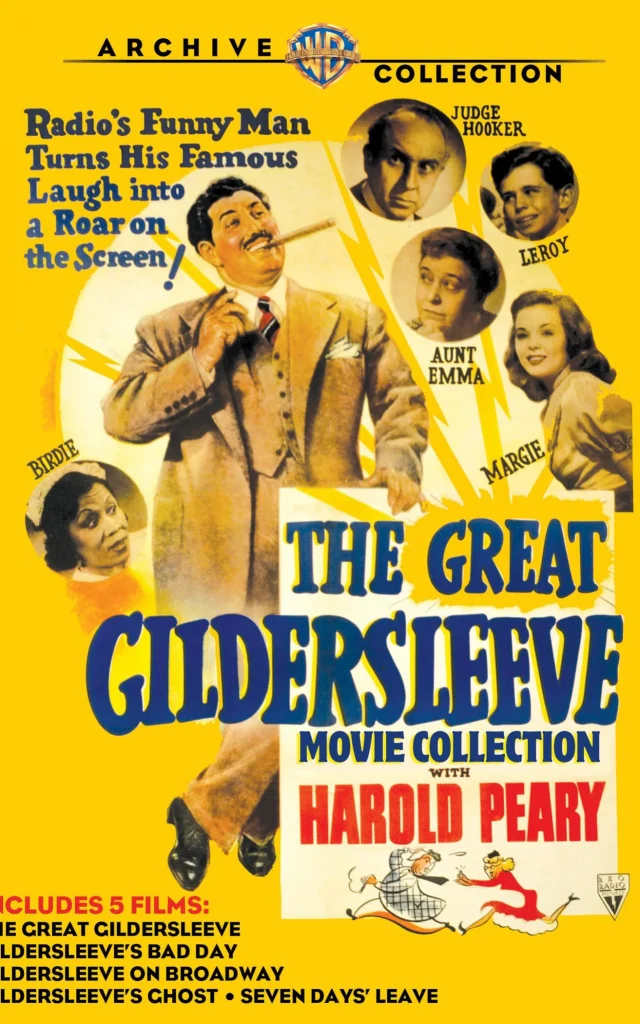

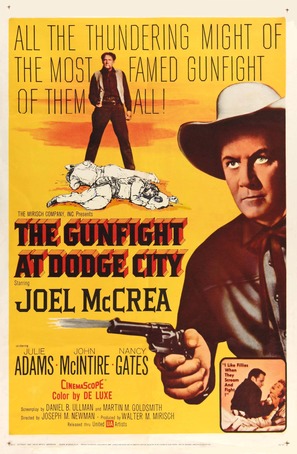

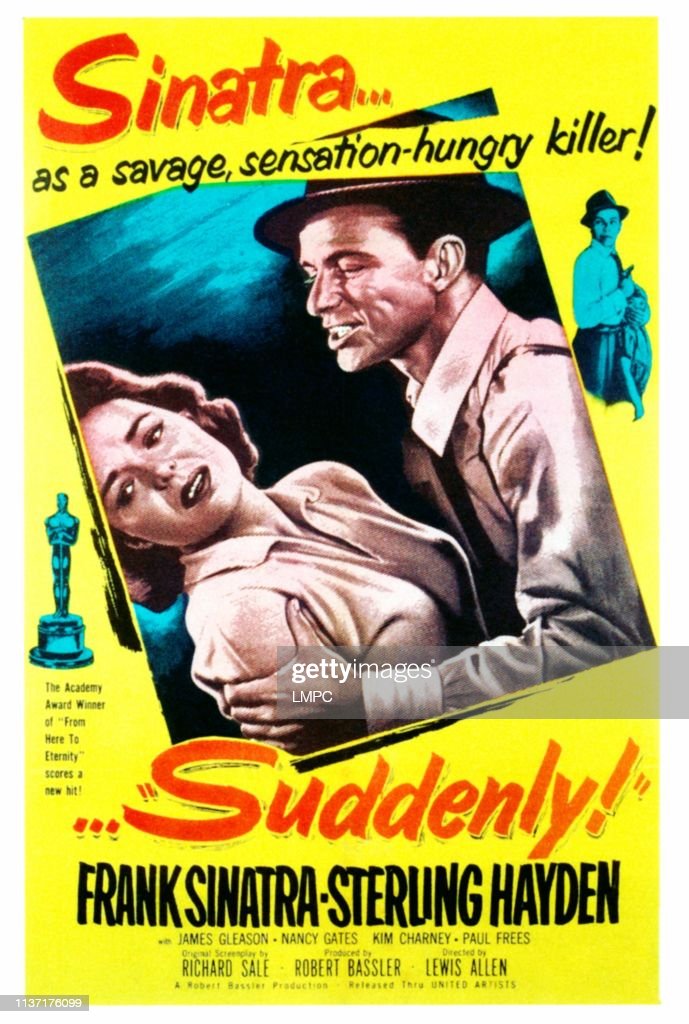

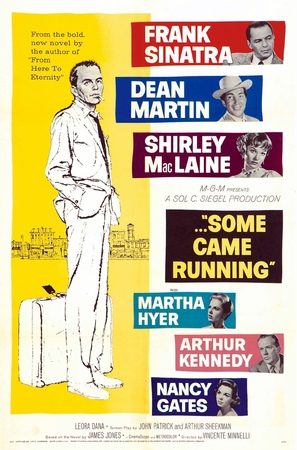

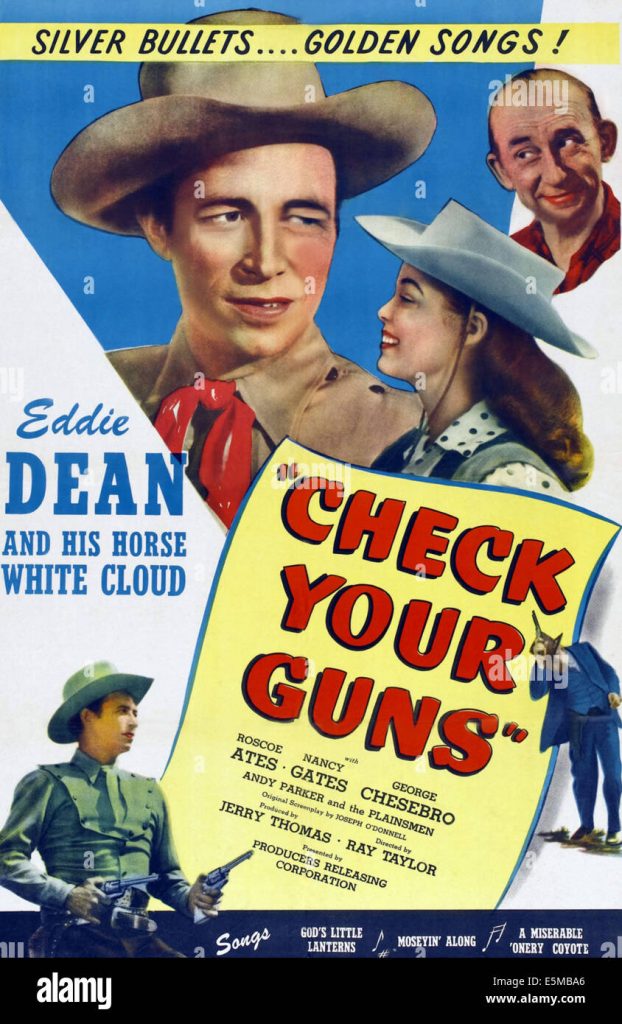

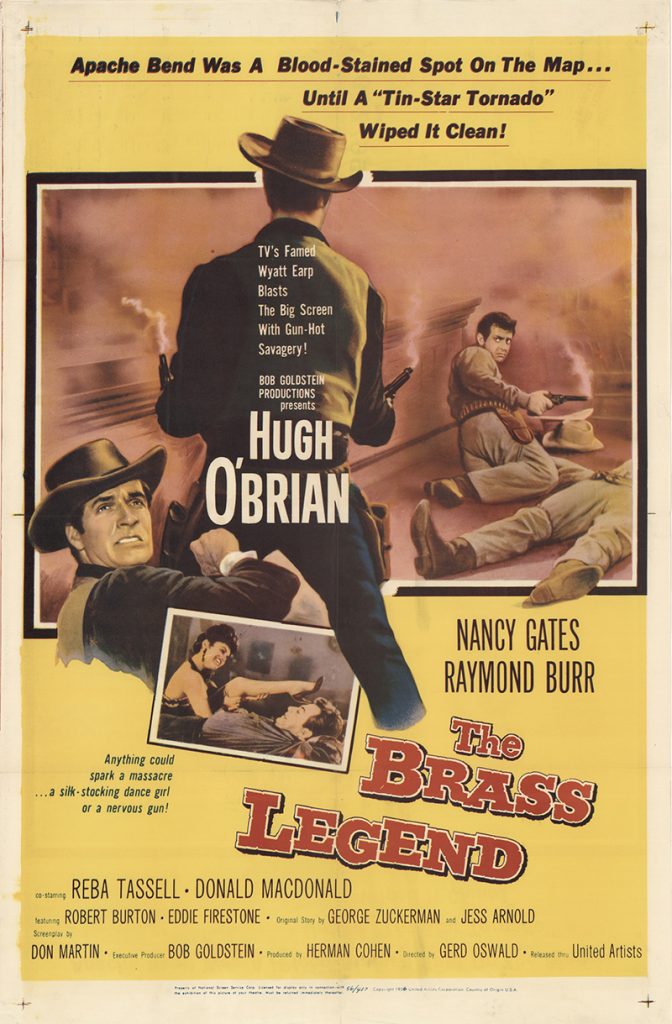

Gates entered acting at a young age, receiving a contract with RKO at the age of 15, which required court approval because of her status as a minor.[ Orson Welles screen-tested her for a role in the 1942 film The Magnificent Ambersons. Although she did not get the role, which went to Anne Baxter, the test paved the way for her future entry into film. That same year she had her first credited role, in The Great Gildersleeve. In 1943 she went on contract with RKO, her first film with them being Hitler’s Children that same year. She began receiving roles in mostly B-movies, many of which were westerns or sci-fi, eventually receiving lead roles as the heroine. In 1948 she starred opposite Eddie Dean in Check Your Guns, and in 1949 she played alongside Jim Bannon, Marin Sais, and Emmett Lynn in an episode of the Red Ryder serial, titled Roll, Thunder, Roll. She would star in several other films over the next ten years, especially in westerns like Comanche Station (1960), and in support roles, most notably in two Frank Sinatra films, Some Came Running and Suddenly.

In total Gates starred or co-starred in 34 films and serials. She retired from acting in 1969.

Nancy Gates. Obituary in “Daily Telegraph” in 2019.

Nancy Gates, who has died aged 93, was an actress who began her career on radio, hosting her own show in Dallas while still in her early teens.

Signed to RKO at the age of 15, she worked in melodramas and crime thrillers, and was often cast as the female lead in Westerns on film and on television.

Born in Dallas, Texas, on February 1 1926, Nancy Jane Gates attended Robert E Lee School, Denton, and was described by a local newspaper as “a child wonder”. At the age of four, she was named official sweetheart of the Texas College band.

In 1933 her mother enrolled her in the Denton Dance School, where she was given a solo as part of the Denton Kiddie Revue and had a feature role in the play A Kiss for Cinderella, followed by a minstrel show in which she and a fellow “Denton Kiddie”, the future femme fatale Ann Sheridan, also starred.

By the time she entered Denton High School, Nancy already had her own radio show.

After a brief spell at the University of Oklahoma she was offered a contract by RKO Pictures. She made her debut in the jungle action adventure, The Tuttles of Tahiti (1942), starring Charles Laughton.

That year Orson Welles tested her for Lucy Morgan in The Magnificent Ambersons, but felt she was a little immature for the role, which he gave to Anne Baxter; he gave Nancy Gates a bit part.

She had her first screen kiss in the 1942 comedy The Great Gildersleeve, after she asked the director Gordon Douglas to give her character more scope.

The following year she appeared in Hitler’s Children, Edward Dmytryk’s propaganda film about the Hitler Youth, and was teamed with Charles Laughton again for the Second World War drama This Land is Mine. She was also in the sequel Gildersleeve’s Bad Day.

There followed a run of B-movies, including the comedy Bride by Mistake and The Master Race, about a Nazi agent who infiltrates a recently liberated Belgian town and tries in vain to turn the inhabitants against the Allies.

By the mid-to-late 1940s, she had slipped down the cast list, though she was busy on radio, and in 1946-47 was in the soap opera Masquerade.

In 1948 she married William Hayes, a Hollywood lawyer and pilot, whom she met when she was a passenger on one of his flights. Away from RKO, Nancy Gates freelanced, taking small roles in such films as the Cecil B DeMille circus epic The Greatest Show on Earth (1952) and the Joan Crawford drama Torch Song (1953).

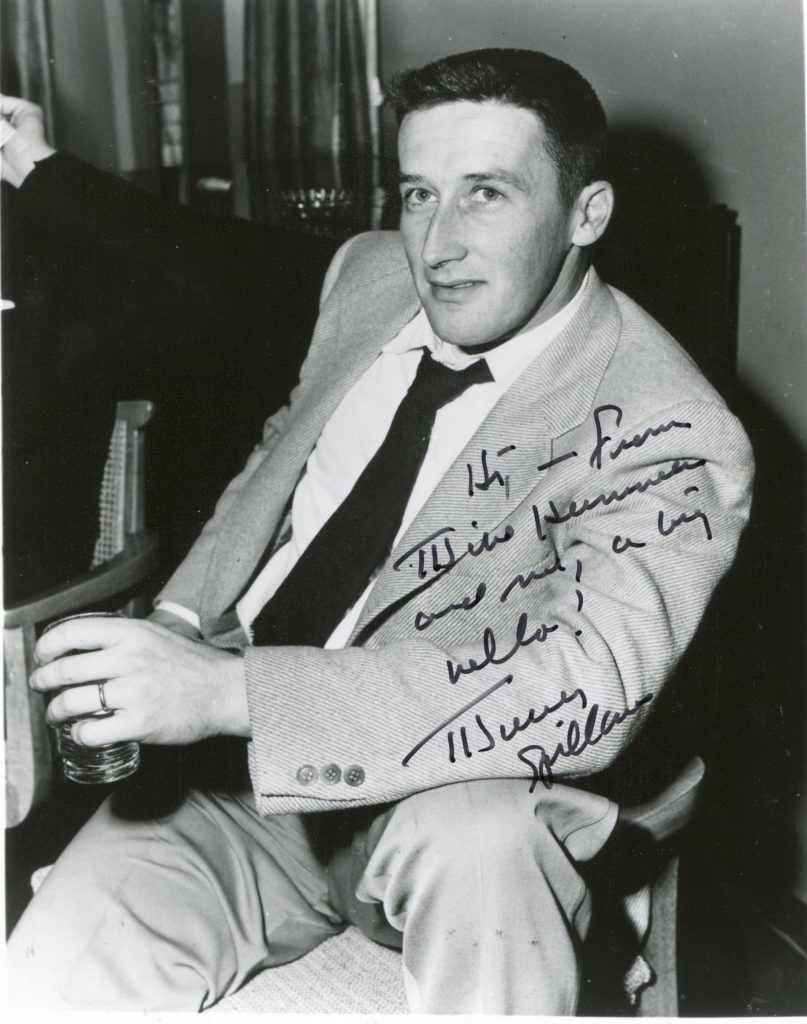

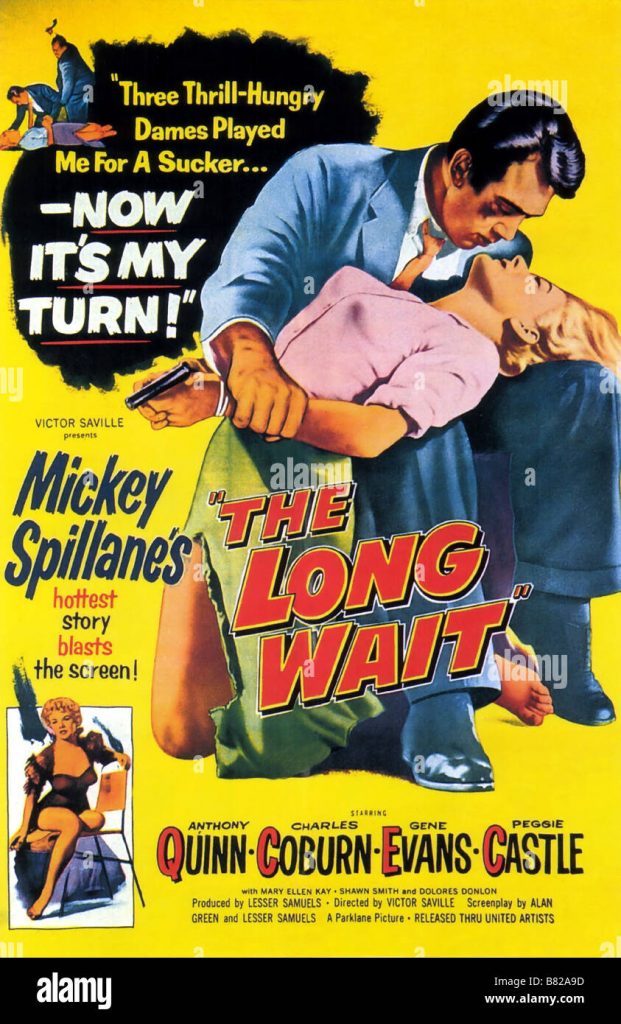

By the middle of the 1950s she was concentrating more on television, though she did enjoy the distinction of shooting a ruthless killer played by Frank Sinatra in the 1954 noir thriller Suddenly. On the small screen there were parts in such shows as Maverick, Rawhide, Laramie, Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Perry Mason.

In 1956 came perhaps her most memorable film, alongside Hugh Marlowe, the early sci-fi adventure World Without End, about a group of astronauts caught in a time warp who find themselves on a future planet Earth populated by mutants.

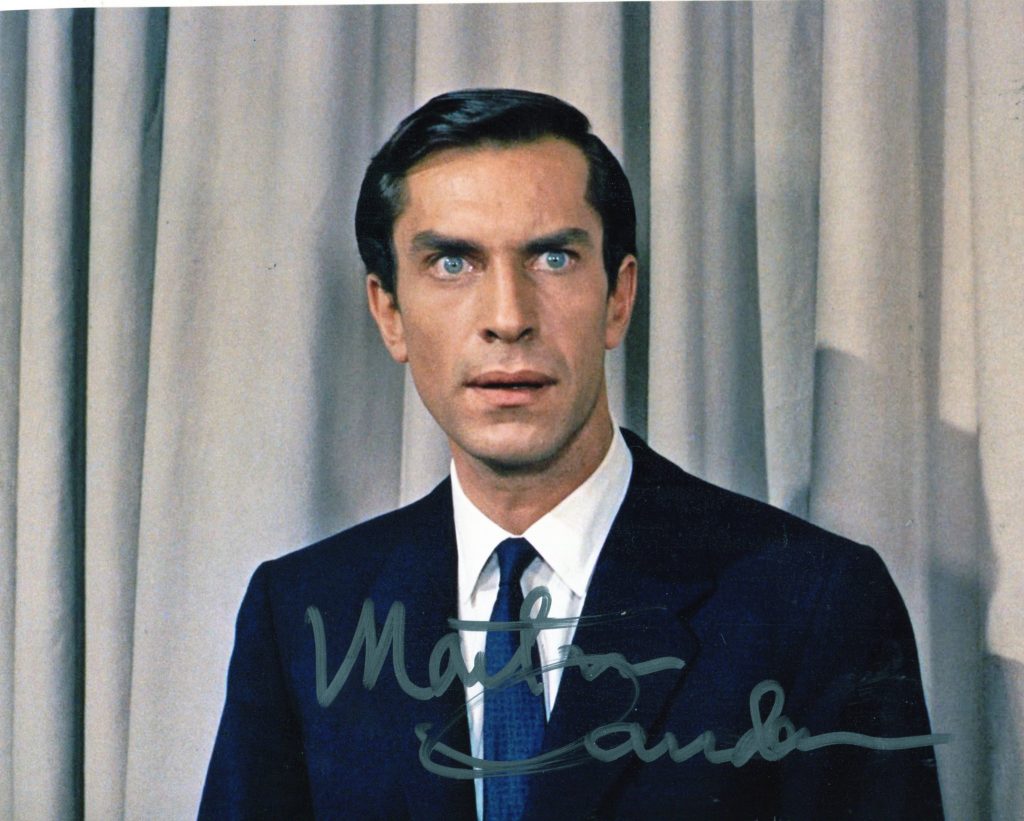

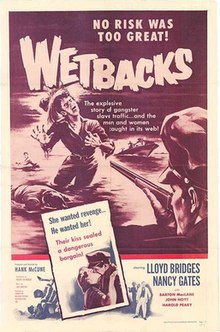

The same year she was in the crime drama Wetbacks, starring Lloyd Bridges, and the crime drama Death of a Scoundrel with George Sanders and Zsa Zsa Gabor, before being reunited two years later with Frank Sinatra in Some Came Running, co-starring Dean Martin and Shirley MacLaine.

Nancy Gates retired in 1969 to spend more time with her family.

Her husband died in 1992 and she is survived by their twin daughters and two sons, who are both Hollywood producers.