Shirley Knight TCM Overview

Shirley Knight is a lovelyactress of the 1960’s who had matured into a powerhouse character actress to-day. She was born in 1936 in Kansas. One of her first films was “Ice Palace” in 1960 with Richared Burton, Robert Ryan, Carolyn Jones and Ray Danton. She starred opposite Paul Newman in “Sweet Bird of Youth” and was one of “The Group” in 1966. Francis Ford Coppola directed her in “The Rain People” in 1969. She continues to appear regularly on television in shows such as “Law & Order”.

TCM Overview:

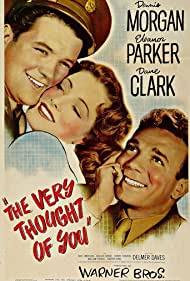

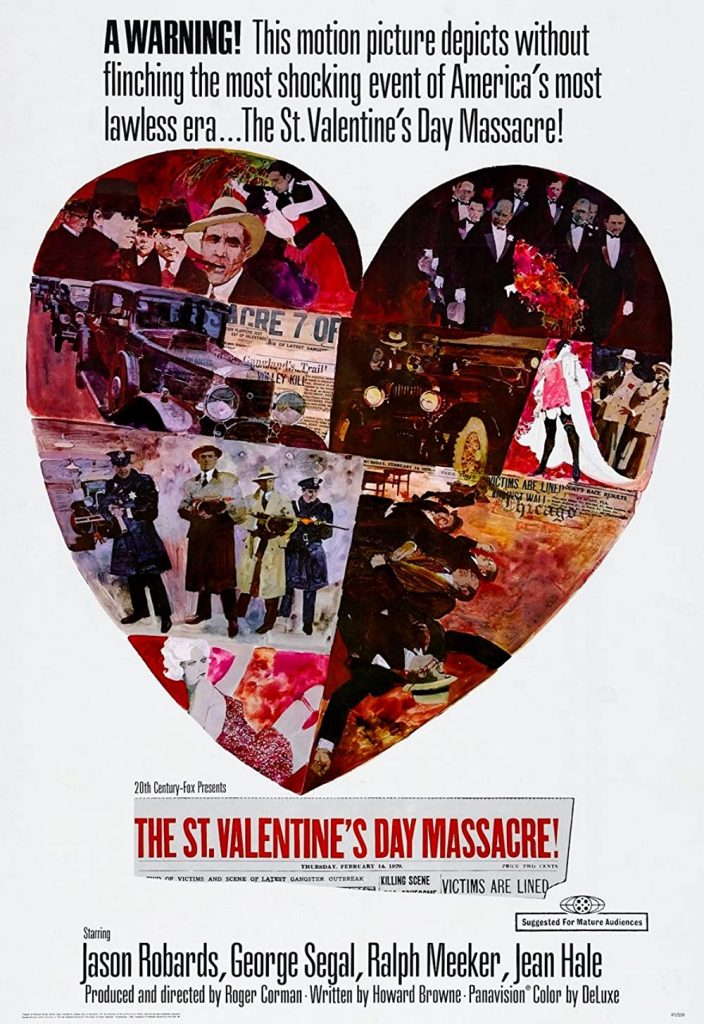

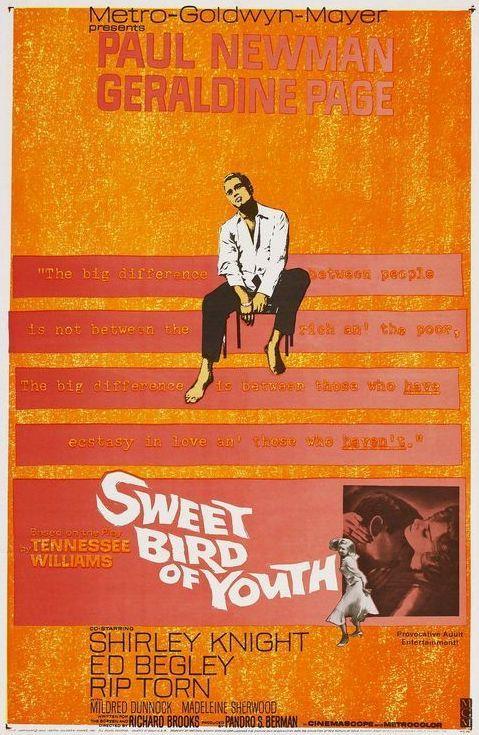

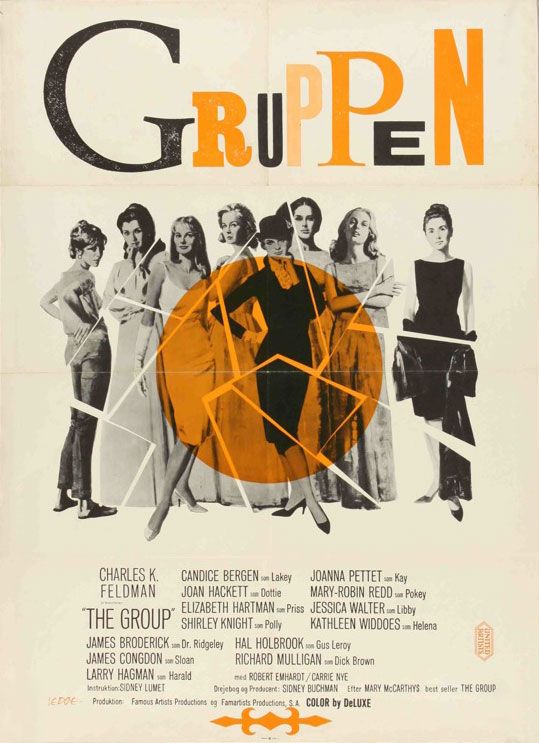

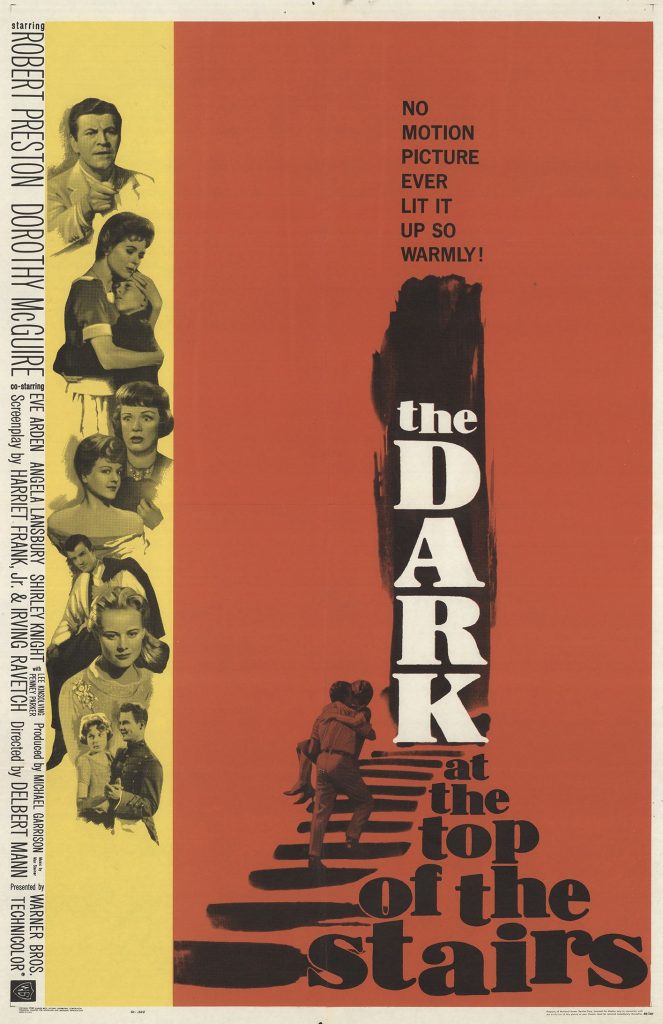

Kansas-born Shirley Knight originally intended to be an opera singer until she saw a touring company of “The Lark” starring Julie Harris and switched to acting. In 1957, she headed west to study at the Pasadena Playhouse where she made her stage debut the following year in “Look Back in Anger”. Knight was put under contract by Warner Bros. and the petite blonde earned critical acclaim and a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination as an Oklahoman in love with a Jew in the screen adaptation of William Inge’s “The Dark at the Top of the Stairs” (1960). She picked up a second nod in the same category as Heavenly Finley, the woman seduced and abandoned by Chance Wayne, in “Sweet Bird of Youth” (1962). In “The Group” (1966), her character found seeming happiness with James Broderick while later that same year she delivered a strong turn as a sluttish white woman who confronts a young black male passenger in “The Dutchman”. After a strong turn as a pregnant woman who runs off with a football player in Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Rain People” (1969), Knight moved to England with her second husband, British playwright John Hopkins and did not act on screen for five years, returning in “Juggernaut” (1974). Her subsequent film roles have generally cast her in maternal roles as in “Endless Love” (1981), “Stuart Saves His Family” (1995) and “As Good As It Gets” (1997).

While she found almost immediate success in films, Knight has a stated preference for stage work. Spurning an offer to play Ophelia to Richard Burton’s “Hamlet”, she opted to co-star with Geraldine Page and Kim Stanley in an Actors Studio production of Chekhov’s “Three Sisters” (1964). She acquired a Tony as Featured Actress in a Play for her turn as a floozy in “Kennedy’s Children” (1975) and has appeared in several classics including twice playing Blanche in “A Streetcar Named Desire”, Lola in “Come Back, Little Sheba” and Amanda Wingfield in “The Glass Menagerie”. More recently, Knight returned to Broadway and netted a Tony nomination for her turn as a woman who refuses to accept that her son committed suicide in Horton Foote’s Pulitzer-winning “The Young Man From Atlanta” in 1997.

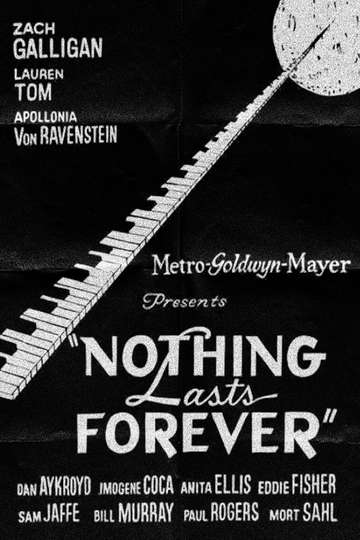

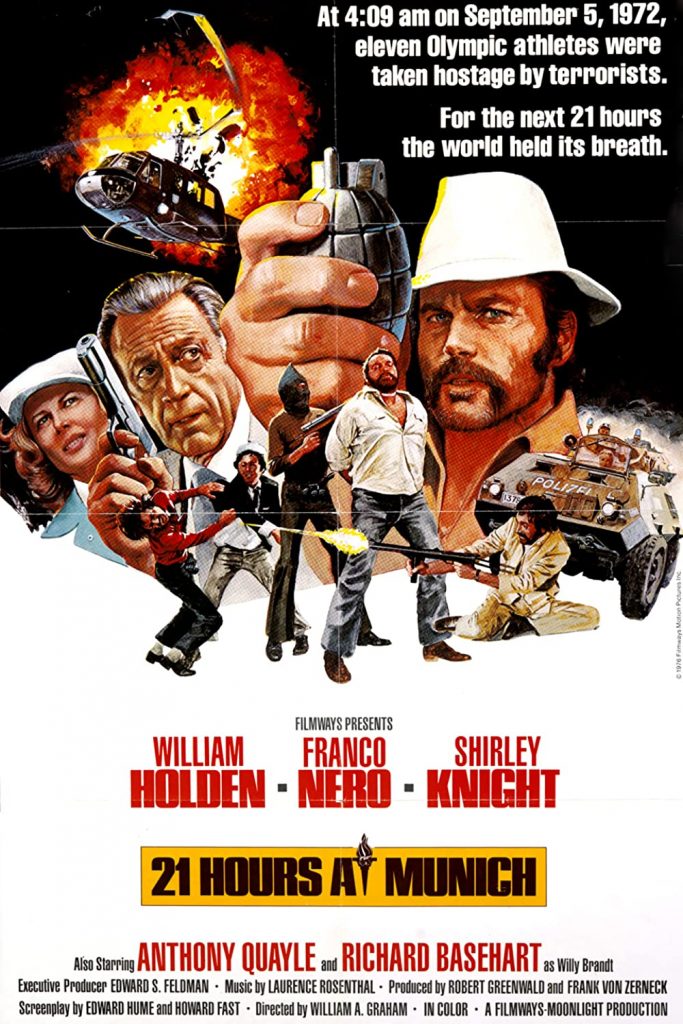

The small screen has also provided the actress with challenging roles. She made her first appearance in the medium in a live broadcast in 1959 and amassed numerous guest credits in the 60s and 70s. Knight co-starred opposite Jason Robards in a “Hallmark Hall of Fame” presentation of “The Country Girl” (NBC, 1974) and Alan Arkin in the above average CBS movie “The Defection of Simas Kudirka” (1978). She offered a strong turn and earned her first Emmy nomination as a concentration camp inmate in the acclaimed “Playing for Time” (CBS, 1980) before picking up the award for a guest appearance as the mother of Mel Harris’ Hope in a 1987 episode of ABC’s “thirtysomething”.

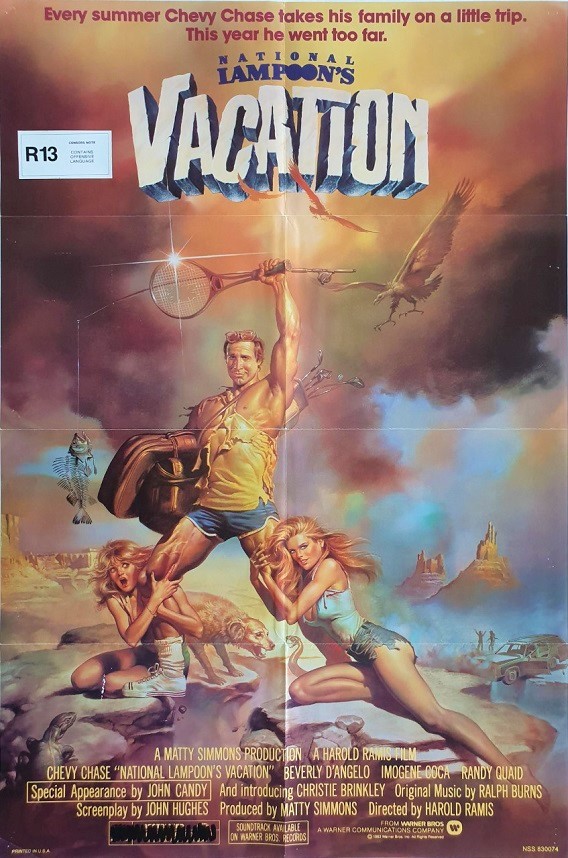

Knight had her first regular series role in the short-lived 1993 CBS drama “Angel Falls”. At the 1995 Emmy Awards, she picked up two statuettes, one for her guest appearance as the mother of a murder victim in an episode of “NYPD Blue” and the second as day care center owner Peggy Buckley who was accused of and tried for child molestation in the fact-based HBO drama “Indictment: The McMartin Trial”. Knight has continued to be a powerful presence in the medium, offering effective supporting turns in such made-for-television fare as “Stolen Memories: Secrets From the Rose Garden” (Family Channel, 1996), “Mary & Tim” (CBS, 1996) and “The Wedding” (ABC, 1998). She returned to regular series work cast as the mother of the titular “Maggie Winters” in the short-lived 1998 CBS sitcom starring Faith Ford. The actress’s schedule remained packed with continual roles in feature films–including “Angel Eyes” (2001), “The Salton Sea” (2002) and “The Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood” (2002).

Knight became a regular fixture on the small screen with guest appearances on such series as “Ally McBeal,” “ER,” “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit,” “Crossing Jordan,” and “Cold Case” and “House,” and in 2005 she began a recurring stint on “Desperate Housewives” as Phyllis Van De Kamp, the meddling mother-in-law of tightly wound Bree (Marcia Cross). The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

Los Angeles Times obituary in April 2020.

Shirley Knight, the Kansas-born actress who was nominated for two Oscars early in her career and went on to play an astonishing variety of roles in movies, TV and the stage, has died. She was 83.

Knight died Wednesday at her daughter’s home in San Marcos, Texas, according to her daughter Kaitlin Hopkins.

Knight’s career carried her from Kansas to Hollywood and then to the New York theater and London and back to Hollywood. She was nominated for two Tonys, winning one. In recent years, she had a recurring role as Phyllis Van de Kamp (the mother-in-law of Marcia Cross’ character) in the long-running ABC show “Desperate Housewives,” gaining one of her many Emmy nominations.

Knight’s first Academy Award nomination for supporting actress came in just her second screen role, as an Oklahoman in love with a Jewish man in the 1960 film version of William Inge’s play “The Dark at the Top of the Stairs.”

She was nominated for a supporting actress Oscar two years later for her performance as the woman seduced and abandoned by Paul Newman in the 1962 film “Sweet Bird of Youth,” based on the Tennessee Williams play.

As success beckoned in 1960, she told columnist Hedda Hopper that she was struggling to keep on an even keel and continue bettering herself as an actress.

“So many actors, once they became famous, lose some beautiful inner thing, something they should try hard to keep,” she said. “They begin to think too highly of themselves and success.”

For a time, she lived in New York, where she studied with Lee Strasberg. She turned down an offer to play Ophelia to Richard Burton’s Hamlet, preferring to appear on Broadway in 1964 with Geraldine Page and Kim Stanley in Anton Chekhov’s “The Three Sisters,” directed by Strasberg.

Her beauty helped bring her roles in such films as “The Group” (1966), based on Mary McCarthy’s novel about the lives of a group of college girls, and “Dutchman” (1967), from Amiri Baraka’s explosive one-act play about a middle-class black man and a sexually provocative white woman. After playing a pregnant woman who runs off with a football player in Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Rain People,” released in 1969, Knight wearied of the Hollywood routine, terming the studio bosses “blockheads.”

Knight moved to England with her second husband, British playwright John Hopkins, with whom she had a daughter, Sophie. (Her first husband was producer Gene Persoff, father of her older daughter, Kaitlin.)

Over the next few years, she raised her daughters and did needlework. But “I decided that acting is what I do best,” she said. The family moved back to the U.S. and Knight returned to films in “Beyond the Poseidon Adventure.” She also appeared in such films as “Endless Love” (as Brooke Shields’ mother), “As Good as It Gets” (as Helen Hunt’s mother) and “Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood.”

Meanwhile, she thrived onstage and in television. She won a Tony award in 1976 as featured actress in a play for “Kennedy’s Children.” Knight played, in the words of the New York Times review, “a very tart tart with an ambition of gold.”

She was nominated for another Tony in 1997 for best actress in Horton Foote’s “The Young Man From Atlanta.” As the Times put it, “The splendid Ms. Knight, who doesn’t waste a single fluttery gesture, brings an Ibsenesque weight to a woman frozen in the role of petulant, spoiled child bride.”

Knight became active in television starting in the 1950s and was nominated for Emmys eight times from 1981 to 2006. She won a guest actress Emmy in 1988 for playing Mel Harris’ mother in “Thirtysomething,” and then won two Emmys in the same year, 1995: for a supporting actress role in the TV drama “Indictment: The McMartin Trial” and for a guest actress role as a murder victim in “NYPD Blue.”

She was born Shirley Enola Knight on July 5, 1936, in the Kansas countryside, 10 miles from the town of Lyons. Her family was musical and she learned to sing, tap dance and play various instruments.

She was the first in her family to enter college, winning a scholarship to a church college in Enid, Okla., then moved to Wichita State University. She appeared in 32 plays in two years and did two seasons of summer stock.

She aimed to become an opera singer, then switched to acting when she saw Julie Harris in a touring company of “The Lark.” She traveled west to study acting at the Pasadena Playhouse. Warner Bros. signed her to a contract.

Knight is survived by her daughters, Kaitlin and Sophie C. Hopkins.