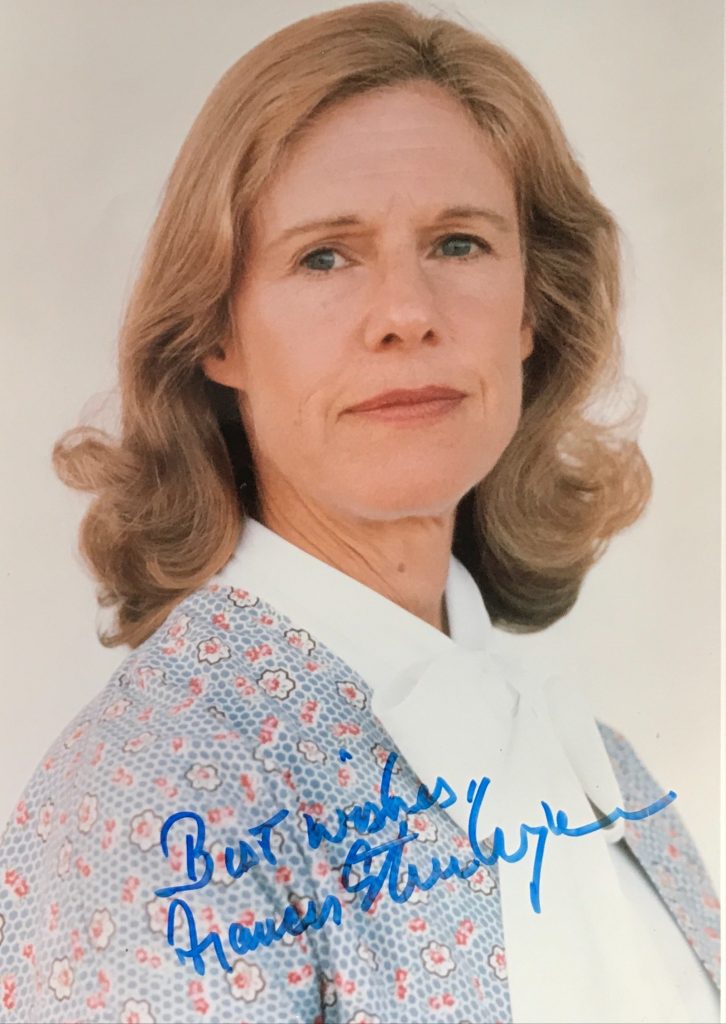

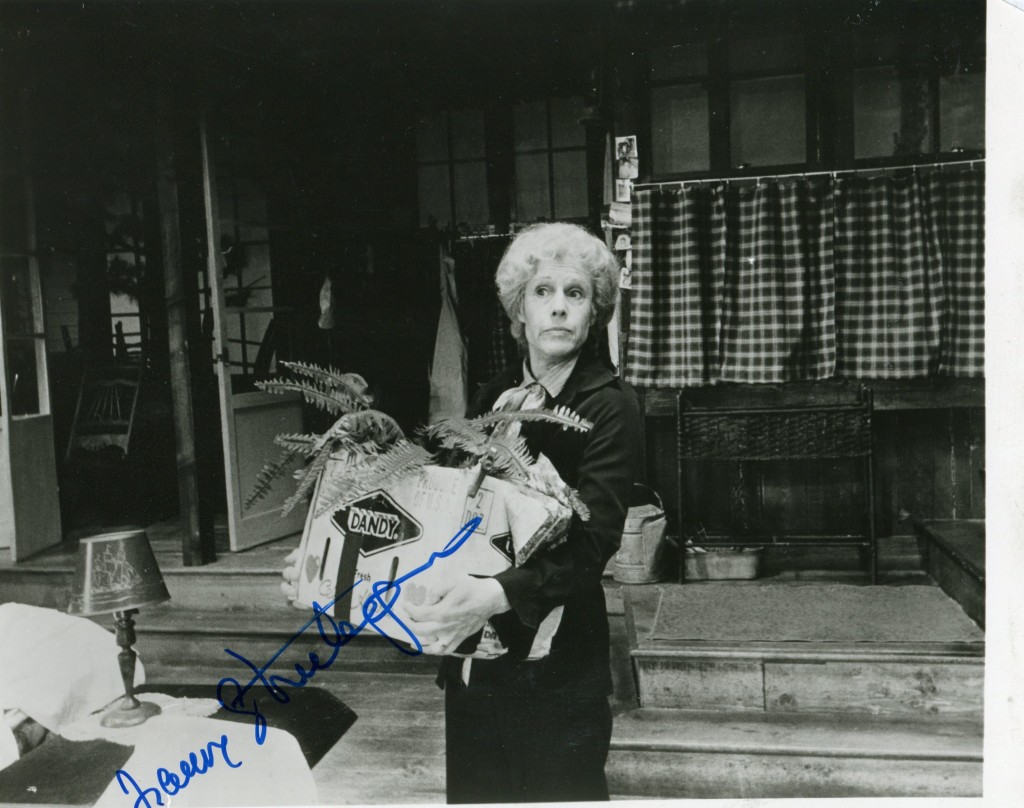

Frances Sternhagen

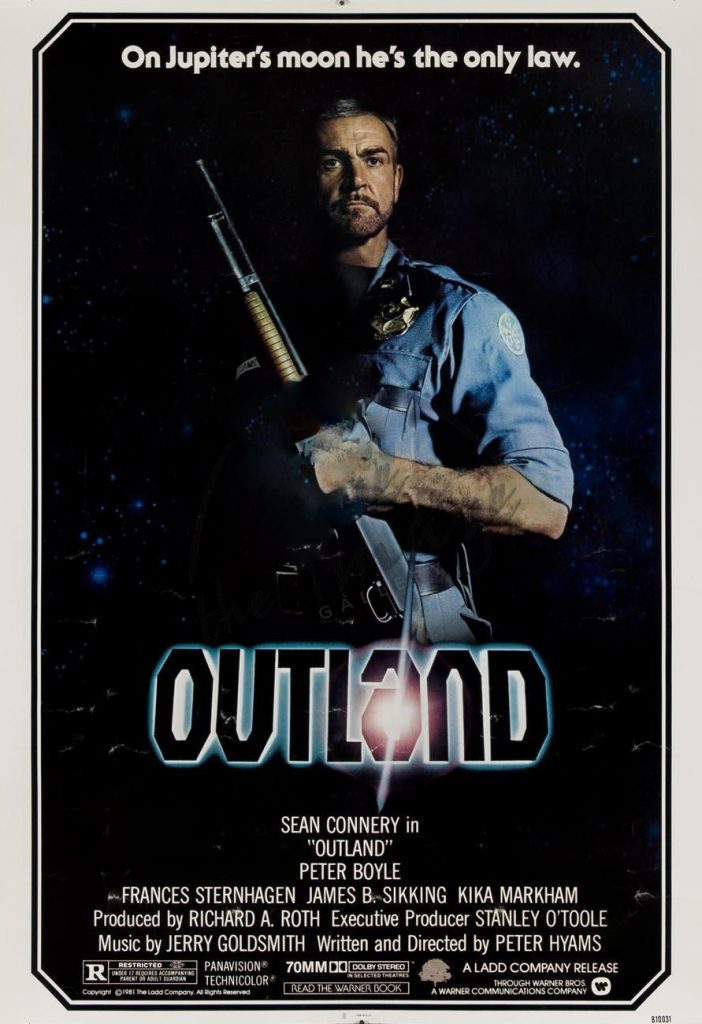

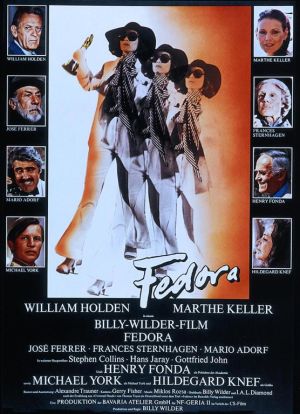

Frances Sternhagen was born in 1930 in Washington D.C. She has won two Tony awards for her acting on Broadway, in 1974 for “The Good Doctor” and in 1995 for “The Heiress”. She made her film debut in 1967 in “Up the Down Staircase” with Sandy Dennis. Her other films include “The Hospital” in 1972, “Fedora”, “Two People” and opposite Sean Connery in “Outland”. On television she was featured in “Cheers” as the mother of postman Cliff.

TCM Overview:

A respected stage-trained supporting and leading player, Sternhagen made her film debut in “Up the Down Staircase” (1967). She subsequently appeared in a wide range of supporting roles, usually as either prim, slightly disapproving characters as well as warmly maternal women. Sternhagen’s credits include the classic “The Hospital” (1971), “Two People” (1973) and Billy Wilder’s “Fedora” (1978).

She won attention for her portrayal as Burt Reynolds’ relative under whose auspices he meets his new love in Alan J. Pakula’s “Starting Over” (1979) and nearly stole the sci-fi thriller “Outland” (1981), providing comic relief and support to marshal Sean Connery. Sternhagen portrayed a prissy co-worker of Michael J. Fox in “Bright Lights, Big City” (1988), Farrah Fawcett’s mother in Pakula’s “See You in the Morning” (1989), Richard Farnsworth’s wife in “Misery” (1990) and John Lithgow’s psychiatrist in “Raising Cain” (1992).

Sternhagen is a familiar face to TV viewers. She is probably best-known for her recurring role as the mother to mailman Cliff Clavin (John Ratzenberger) on the NBC comedy “Cheers”. Sternhagen began appearing on the small screen in the 1950s and spent the better part of the late 60s and early 70s in a variety of roles on daytime soaps (“Love of Life”, “The Doctors”, “The Secret Storm” and “Another World”). In primetime, she has played regular supporting roles in everything from sitcoms (“Under One Roof”) to drama (“Stephen King’s Golden Years”).

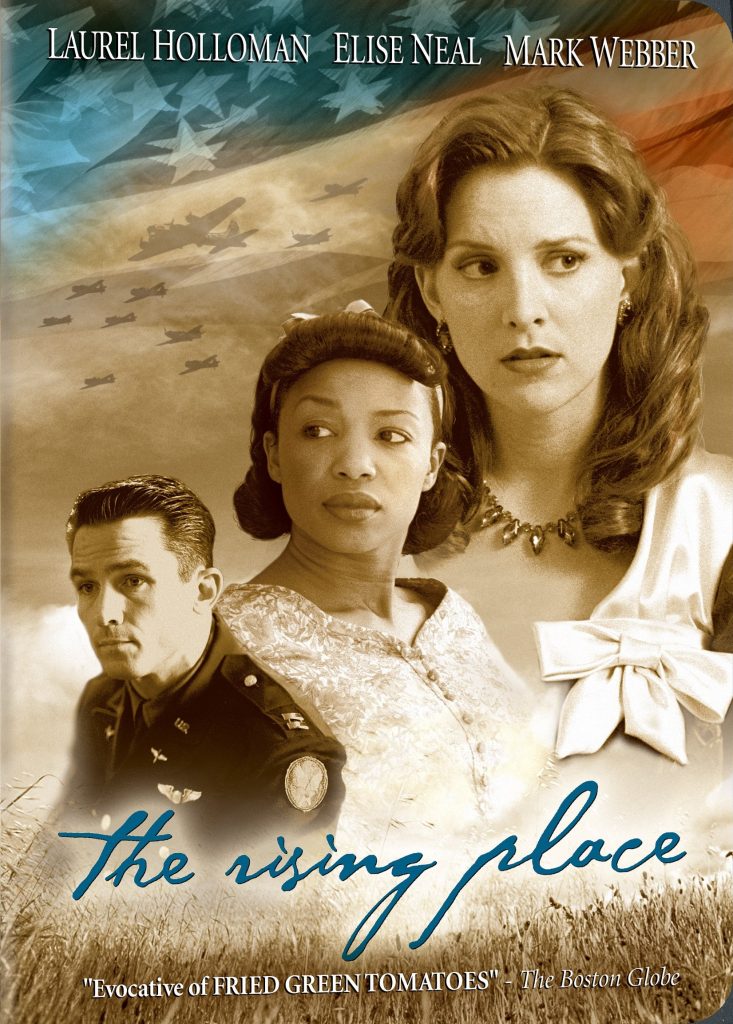

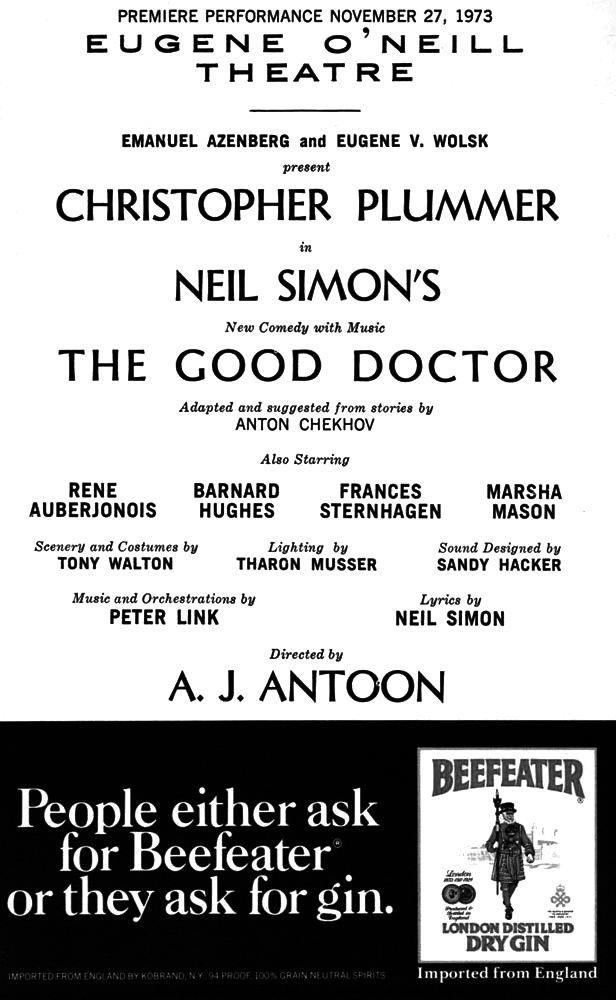

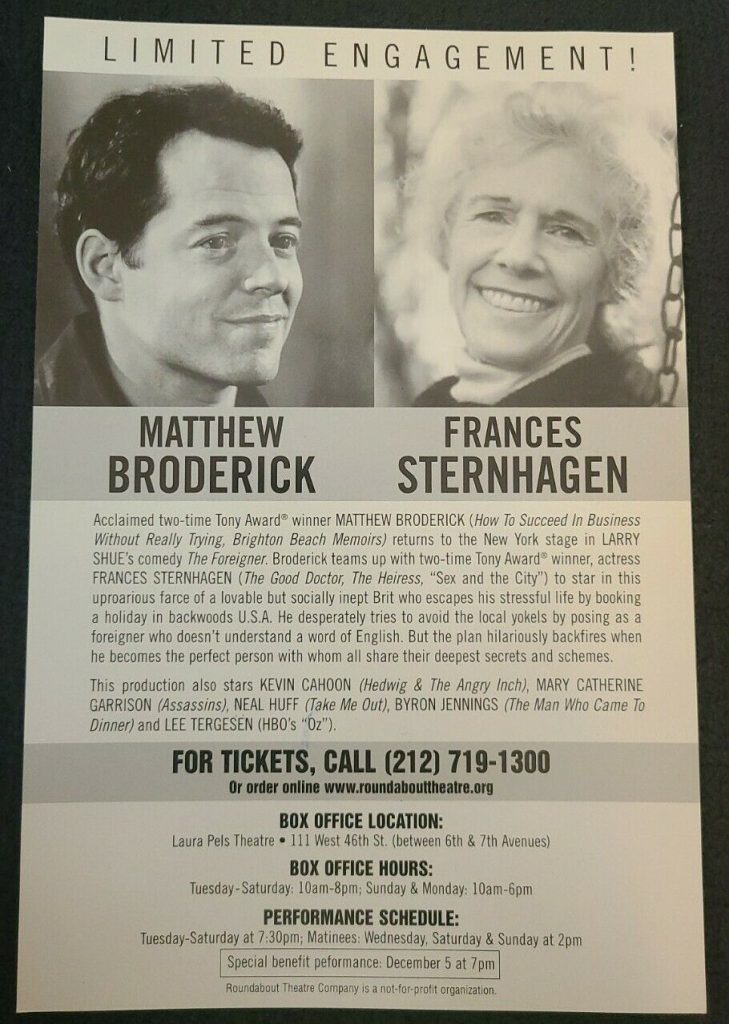

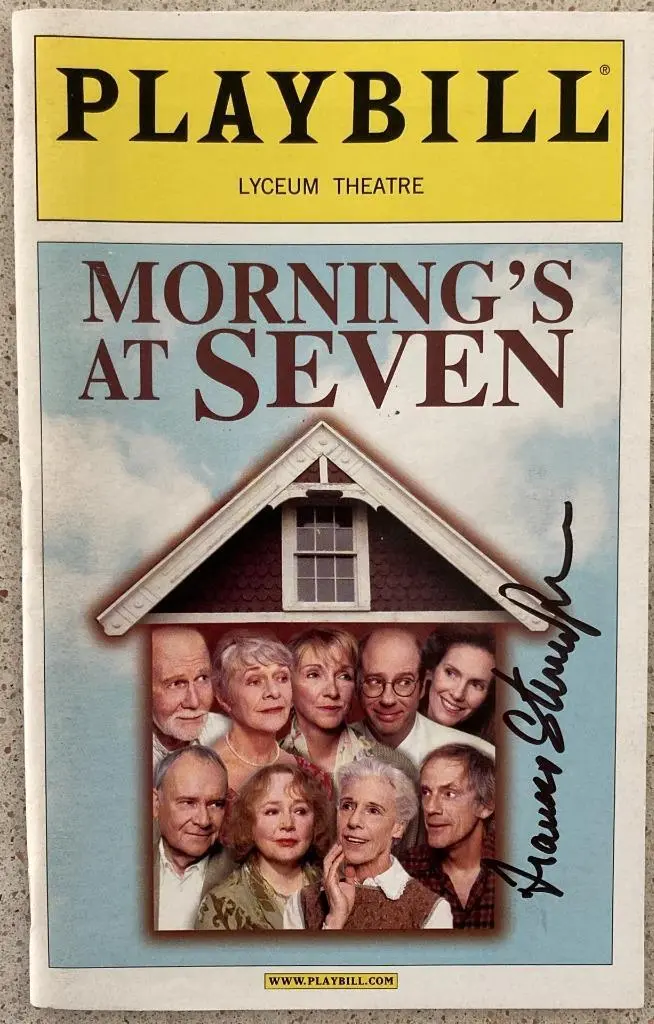

Sternhagen also has extensive stage credits in everything from classic plays to musical comedies. She has received two Tony Awards for Best Supporting Actress in a Play for Neil Simon’s “The Good Doctor” (1974), based on Chekhov works to a revival of “The Heiress” (1995), based on the Henry James’ novella. Sternhagen was married to actor Thomas A. Carlin from 1956 until his death in 1991.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

The Guardian obituary in 2023:

Frances Sternhagen obituary

Award-winning stage, film and TV actor who had memorable roles as meddling mothers in Cheers and Sex and the City

Ryan GilbeyMon 4 Dec 2023 17.32 CET

With her shrewd blue eyes and twitching dormouse nose, the actor Frances Sternhagen, who has died aged 93, could turn on a dime between consoling warmth and implacable frostiness. She was a multiple Emmy nominee for her guest appearances as two comically meddling mothers. In Sex and the City, between 2000 and 2002, she played Bunny, who can manipulate her pampered son, Trey (Kyle MacLachlan), into doing her bidding simply by squeezing his wrist.

Oblivious to boundaries, Bunny enters his apartment late at night to smear Vicks VapoRub on his chest; his wife, Charlotte (Kristin Davis), who is sleeping beside him, wakes up and joins in. “It is both sick and erotic, and Franny was up for it,” said the show’s executive producer, Michael Patrick King. “It’s always more fun to be obnoxious,” said Sternhagen.

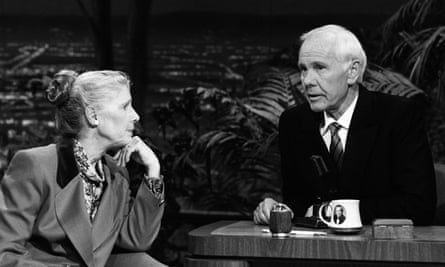

She made seven appearances between 1986 and 1993 in the sitcom Cheers, set in a Boston bar. She played Esther Clavin, the mother of one of the regular patrons, the droning postal worker Cliff (John Ratzenberger). In an episode from the fifth season entitled Money Dearest, Cliff brokers a romance between Esther and an ageing millionaire who has no family to inherit his wealth.

When he dies, the formerly reserved Esther breaks down sobbing in Cliff’s arms, only for him to lose patience despite having initially encouraged her outpouring. “You know, there’s a fine line between expressing your feelings and blubbering,” he mutters.

In Esther’s final episode, at the end of the 11th season, Cliff installs her in a retirement home before changing his mind when he claps eyes on the bill.

She also played the regal grandmother of Dr John Carter (Noah Wyle) on ER between 1997 and 2003, and the mother of the deputy police chief played by Kyra Sedgwick on The Closer (2006-12). “I was big on playing mothers,” she said. “Been playing them since I was five.”

It was theatre, though, that was Sternhagen’s great passion. She won her first Tony award in 1974 for The Good Doctor, Neil Simon’s comedy based on stories by Chekhov, in which 27 roles were shared between her and four co-stars, including Christopher Plummer and Marsha Mason. Her second Tony came in 1995 for playing the widowed Aunt Penniman in The Heiress, adapted from Henry James’s Washington Square. The New York Times called her performance “infinitely sad.”

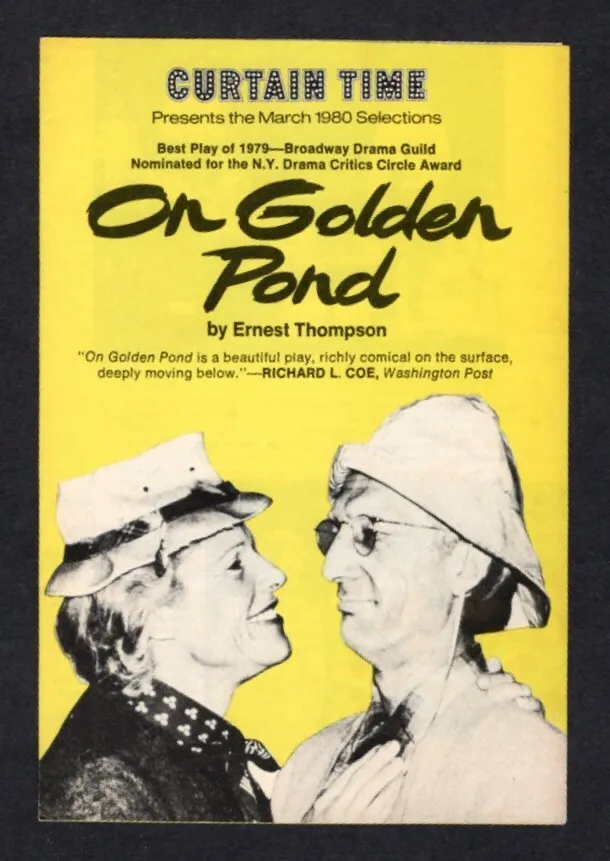

She also played the female leads in two stage dramas which were later turned into successful films. In 1979, she originated the part of Ethel Thayer, the devoted wife enjoying her umpteenth summer with her ailing husband at their holiday home, in On Golden Pond. Sternhagen had just turned 49 when the show opened, making her around 20 years younger than Ethel.

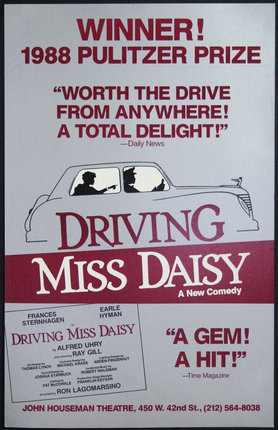

Ageing up was also required in 1988 when she took over from Dana Ivey in Driving Miss Daisy. As the retired teacher who develops an unlikely friendship with her African-American chauffeur, Sternhagen, then 58, was required to embody the title character from her early seventies into her late nineties. In both plays, the actor’s sharply glinting intelligence, which was palpable in even her softest characters, added steel to material that could tend toward the lachrymose.

When On Golden Pond and Driving Miss Daisy were adapted for cinema, she was sanguine about being replaced respectively by Katharine Hepburn and Jessica Tandy, both of whom went on to win Oscars for those performances. “Making a movie is an expensive proposition,” she reasoned in 1992. “If they can get Katharine Hepburn, they’re going to take Katharine Hepburn. It hurts a little, but I’ve gotten used to it really.”

She recalled being introduced to Hepburn backstage during the run of On Golden Pond. “She told us how much she liked our performances. And we knew that she was brought in to see the show to see whether she wanted to do the movie.”

Sternhagen still got her share of film work. She played the servant of a reclusive film star in Billy Wilder’s elegiac Fedora (1978), and a woman helping to set up her newly single brother-in-law (Burt Reynolds) on a blind date in the romantic comedy Starting Over (1979). In Outland (1981), which relocated the plot of the western High Noon to one of Jupiter’s moons, she was the doctor who becomes the only ally of the hero (Sean Connery in the Gary Cooper role) as he awaits the assassins sent to kill him.

In Rob Reiner’s Misery (1990), adapted from Stephen King’s novel about a psychotic fan (Kathy Bates) terrorising her favourite novelist (James Caan), Sternhagen and Richard Farnsworth were delightful as an easy-going sheriff and his fondly teasing wife. Their miniature sketch of marital harmony offset the dysfunctional central relationship, providing valuable relief from its hothouse claustrophobia.

In another King adaptation, The Mist (2007), she was a teacher who opts to die in a suicide pact rather than be left to the mercy of monsters. In Julie & Julia (2009), Sternhagen played Irma Rombauer, writer of The Joy of Cooking, who disabuses the budding author and chef Julia Childs (Meryl Streep) of the notion that her career has been a piece of cake.

Sternhagen was born in Washington, DC, to John Sternhagen, a tax court judge, and Gertrude (nee Hussey), a former nurse who later became a volunteer community worker. She was educated at the Potomac and Madeira preparatory schools in McLean, Virginia, and at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. She majored in history until her professor nudged her towards drama after seeing her silence a campus dining hall with a speech from Richard II.

After graduating in 1951, she taught drama at Milton Academy in Milton, Massachusetts. “I always acted, but I didn’t have the nerve to go into the theatre until I had taught for a year,” she said in 1981. “I thought I would try it, see if I liked it, and then get out. But you never get out. It’s an addiction.”

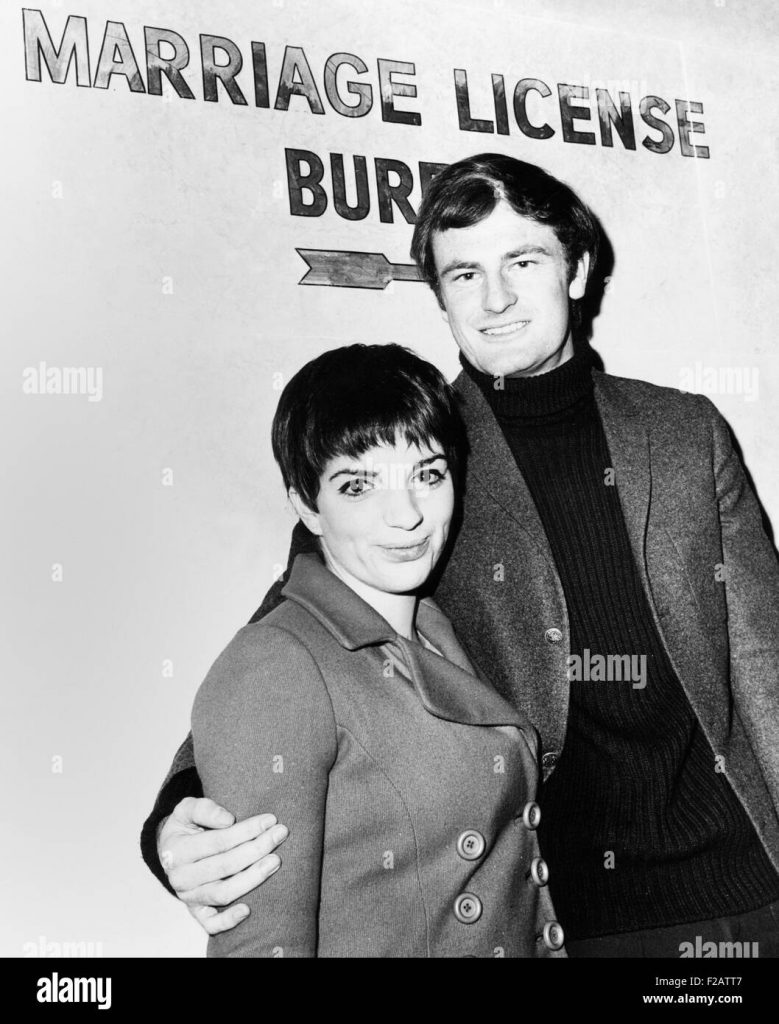

She took acting classes at Catholic University, Washington, where she met her future husband, the actor Thomas Carlin, with whom she went on to have six children.

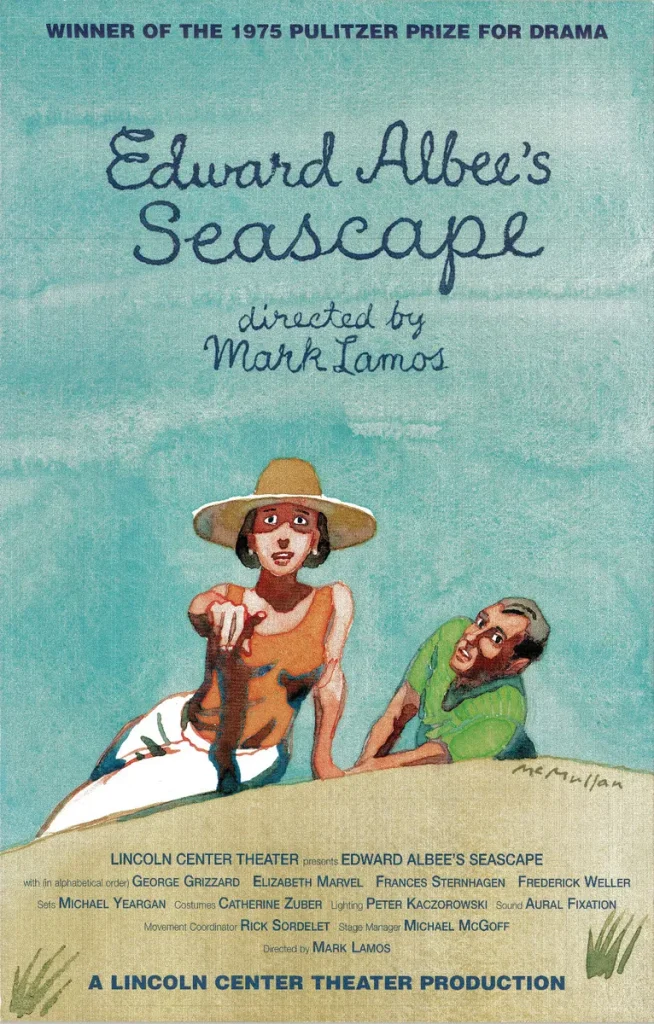

She made her New York debut in 1955 in Jean Anouilh’s play Thieves’ Carnival, and her Broadway debut the same year in Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth. Her final Broadway performance was 50 years later in Edward Albee’s Seascape, while her last stage role was opposite Edie Falco in The Madrid in 2013.

Her final movie was Reiner’s comedy And So It Goes (2014) with Michael Douglas and Diane Keaton. The difference between the two art forms was simple, she said. “You don’t use your face as much in film. It has to come through your eyes.”

In 1973, she said: “I think of myself as a character actor. Character actors like to put on faces and find out what makes oddballs come alive.” Stardom was of no interest to her. “All I really want is to be able to work in good material with good people.” She got her wish.

Thomas died in 1991. She is survived by her children, Paul, Amanda, Tony, Peter, John and Sarah, nine grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Frances Sternhagen, actor, born 13 January 1930; died 27 November 2023