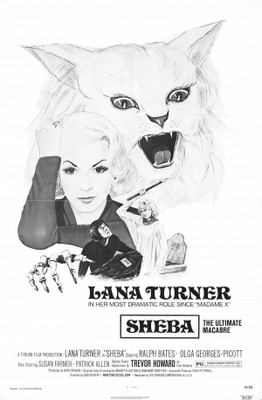

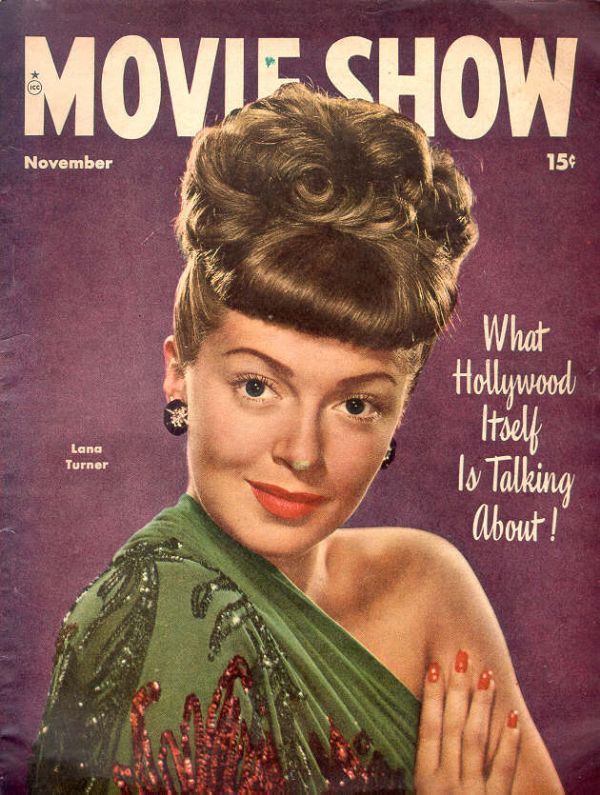

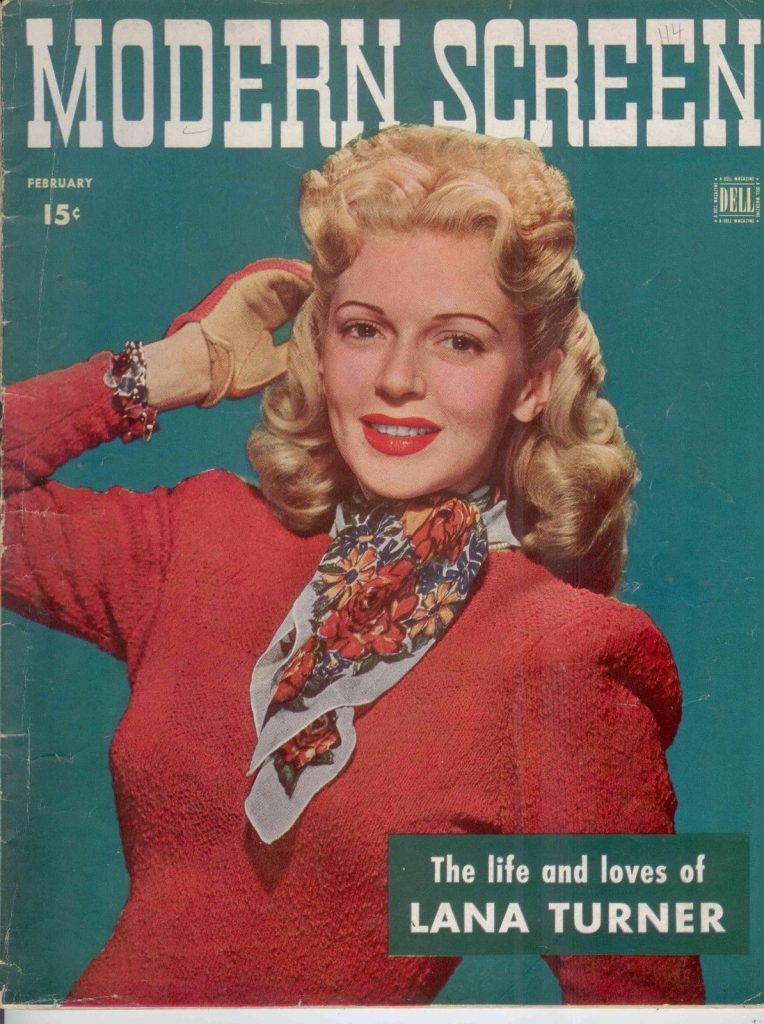

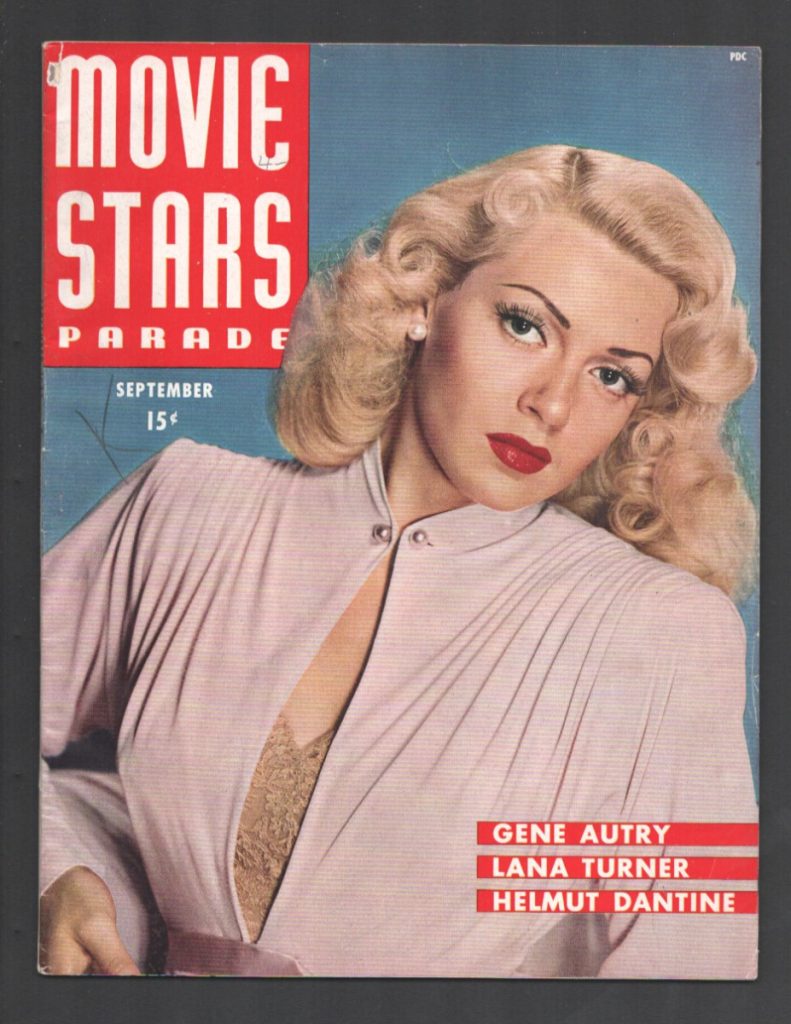

Lana Turner was one of the giants of the Golden Age of Hollywood. She was born in 1921 in Wallace, Idaho. Her movie debut came in 1937 in a small but telling part in “They Won’f Forget”. By 1941 she in such leading roles as “Johnny Eager” and “Ziegfeld Girl”. Her films include “Green Dolphin Street”, “The Bad and the Beautiful”,

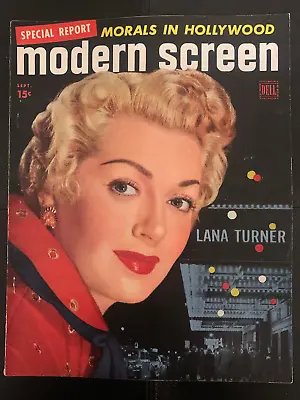

In her reign as a movie goddess of the 1940s and early 1950s, Lana Turner came to crystallize the opulent heights to which show business could usher a small-town girl, as well as its darkest, most tragic and narcissistic depths. In her years as a top box office draw, she and longtime studio MGM forged her statuesque form into any number of pop cultural effigies: the stuff of both starry-eyed legend and tabloid-feeding frenzies; of coquettish sensuality to the G.I.’s of World War II; and later of smoldering elegance, a bedazzling glamour girl and the archetypal, scheming femme fatale. Her apocryphal “discovery” at Schwab’s Drug Store made her a textbook example of sun-drenched Hollywood dream-making, even as she would become a queen of the darkling plane of film noir as a sultry human pressure cooker erupting with lust and malice in her most fondly recalled film, “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (1946). But more visceral, real-life noir would shadow her through a rollercoaster journey of ill-considered and scandalous marriages and relationships, a legacy most ignominiously highlighted by a violent mobster bleeding to death in her home, leading to a tearful testimony in court that the press would snarkily call “her greatest performance.”

A linchpin in a American Dream myth the Hollywood studios liked to shill in those days, the story went that Billy Wilkerson, publisher of the influential trade paper The Hollywood Reporter, “discovered” Judy Turner sipping a soda at Schwab’s Drug Store, the Sunset Boulevard establishment whose lunch counter had become a hangout for showbiz insiders. In truth, Judy had skipped out of school to sneak a cigarette, and did so just across the street from Hollywood High at the Top Hat Café (or, alternatively, the nearby Currie’s Ice Cream Parlor). Wilkerson, sitting across from her at a U-shaped counter and indeed stunned by her beauty, asked the counterman who she was and if she would consent to talk to him. Turner demurred, until the counterman vouched for Wilkerson, who asked what would become a “player” cliché thereafter, “How would you like to be in the movies?” Turner famously replied that she would have to ask her mother, and Wilkerson left her with his business card. Judy kept the card to herself for a couple days, reticent to tell her mother she had talked to a stranger, but when she did, they learned Wilkerson was one of the most powerful men in town. Mildred called him immediately.

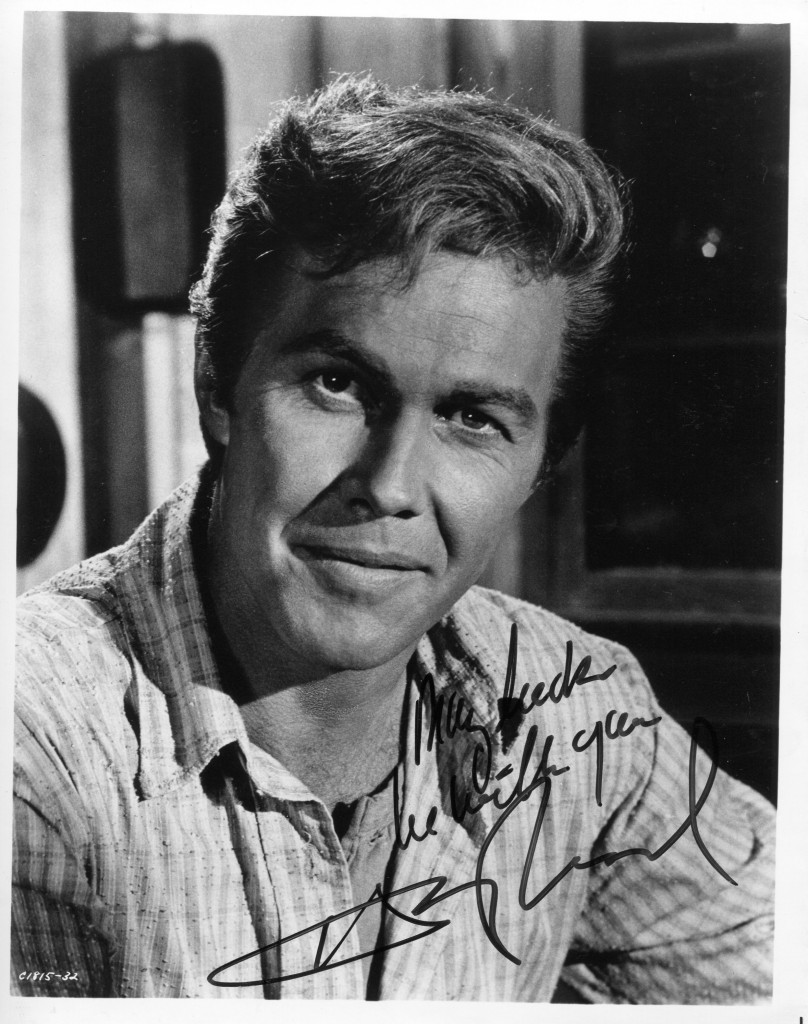

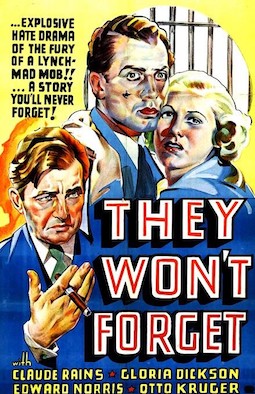

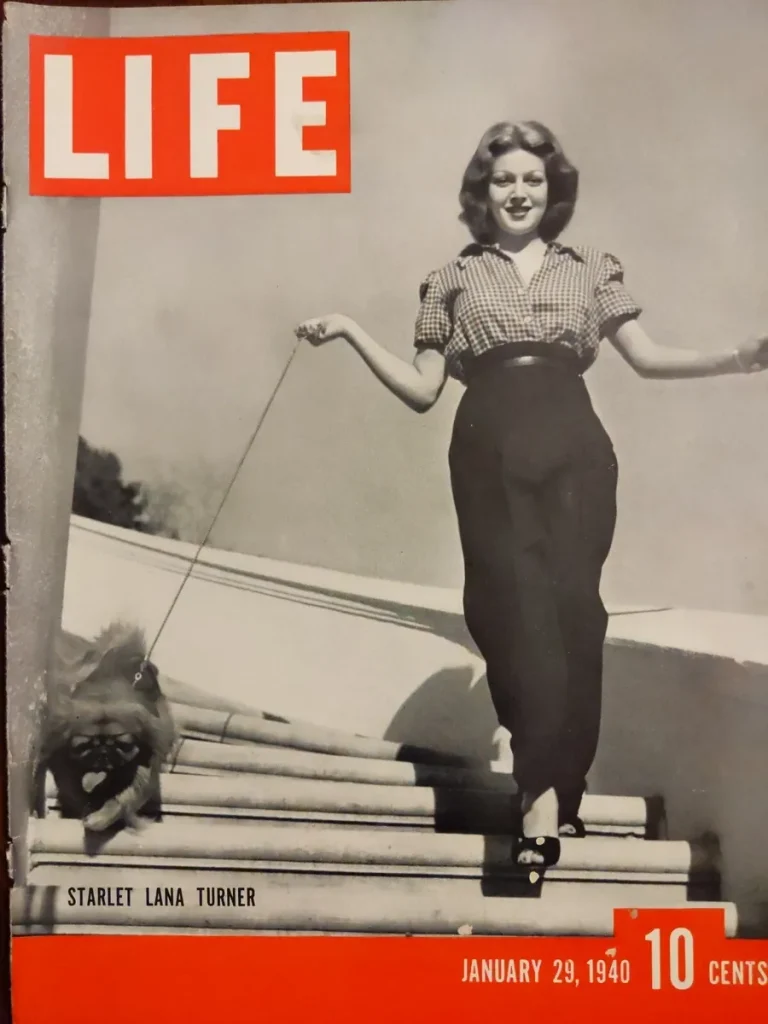

Wilkerson wound up fast-tracking Turner to the talent agency of Zeppo Marx, of the famed Marx Brothers, and from there to Warner Bros. casting honcho Solly Biano, who brought her almost immediately to director Mervyn LeRoy, then prepping a film calling for someone of her type. Still naive to Hollywood politesse, Turner showed up in an anything-but-glamorous cotton dress, her hair rumpled, which actually wowed LeRoy. She got the small but pivotal part as the sweet, virginal college student murdered in a Southern city in “They Won’t Forget” (1937). LeRoy even helped her brainstorm a new glamorous marquee name, Lana Turner. The whirlwind did not stop there; in her brief appearance lithely walking down a street, her form-fitting wool sweater over her curvaceous upper torso seeded her reputation among slavering new fans as “the Sweater Girl,” which also came to describe a genre of pin-up model. Wilkerson’s publication did its part to highlight the new arrival, noting in its review of Turner’s “vivid beauty, personality and charm.”

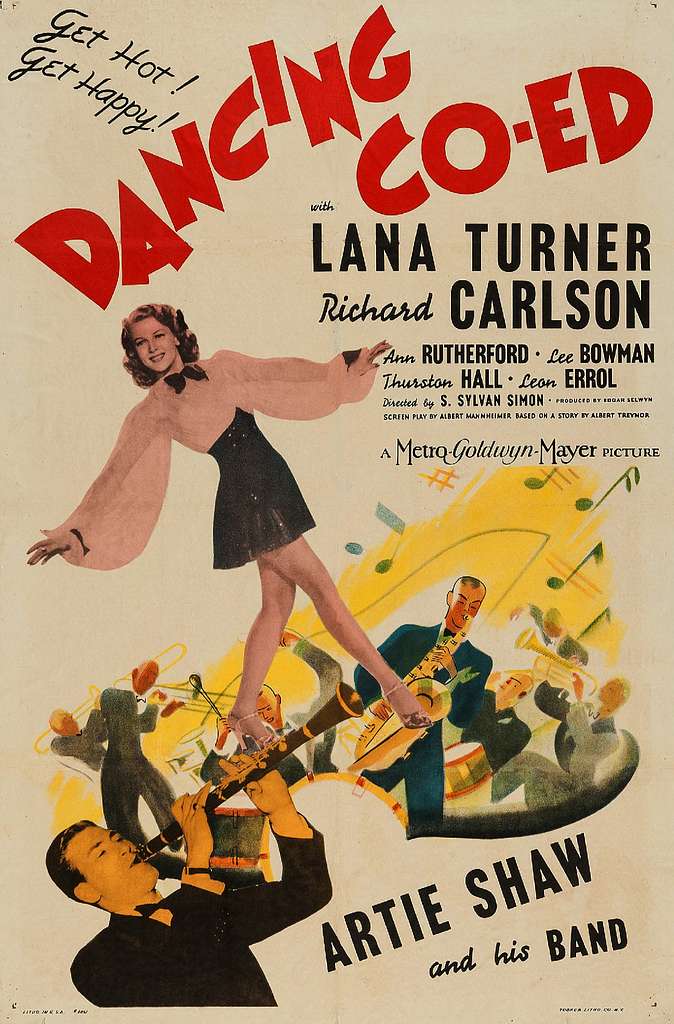

Her early roles actually were more notable for off-set foibles than for the actress realizing her deeper talents as of yet. In the Gary Cooper vehicle “The Adventures of Marco Polo” (1938), Turner played an Asian maid, a make-up effect supplemented by shaving off her eyebrows; they never grew back, forcing her to draw on false eyebrows the rest of her life. The next year, she scored the lead in a fluffy MGM B-comedy, “The Dancing Co-Ed” (1939), where she had the mixed fortune of working with one of the most popular musical artists of the time, big bandleader and notorious ladies man, Artie Shaw. Though Shaw considered motion pictures beneath him, he took notice of the 17-year-old castmember and asked her to dinner. She agreed to lunch, but remained unimpressed, thinking him “one of the most egotistical people I’ve ever met.” She had begun seeing lawyer and fellow womanizer Greg Bautzer, but by February 1940, Bautzer had thrown her over for the considerably older Joan Crawford. Still angry with Bautzer, the ever impulsive Turner accepted a date with Shaw and eloped with him that night to Las Vegas, NV. But the marriage quickly soured, as the notoriously headstrong Shaw became abusive, demanding she assume workaday household duties impossible with her studio schedule. In September, they divorced, with Bautzer stepping in to do the legal legwork. Turner later admitted she had become pregnant by Shaw but had had an abortion, then illegal but often enabled by the studios in their efforts to insulate their contract talent from scandal.

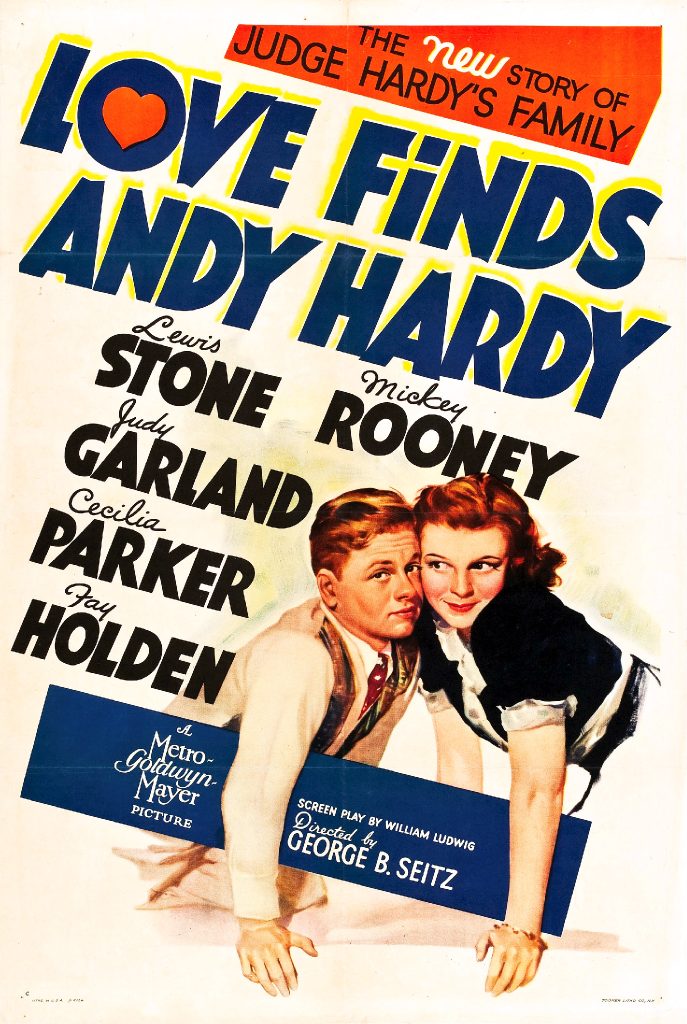

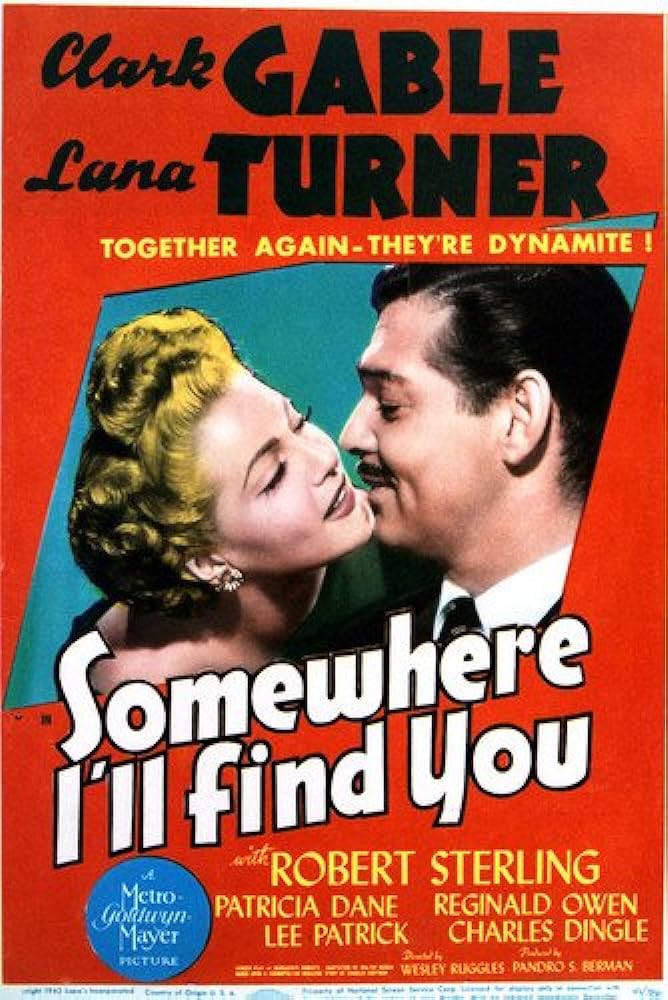

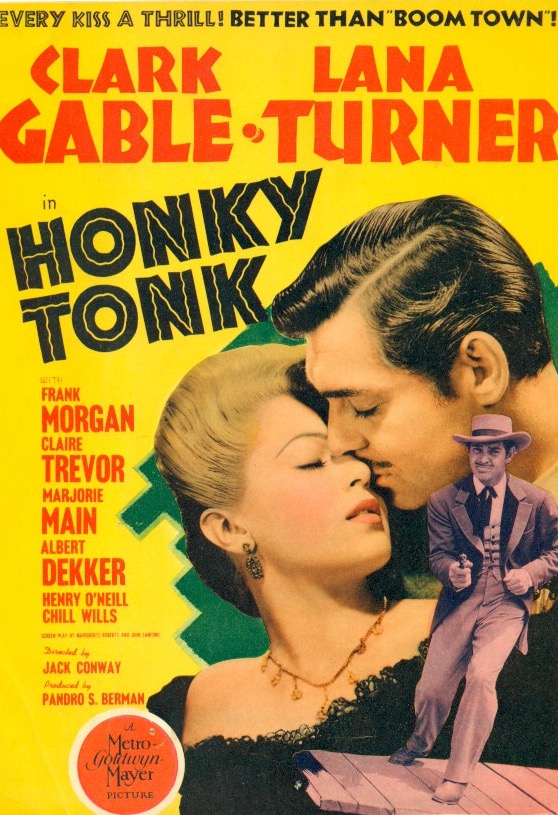

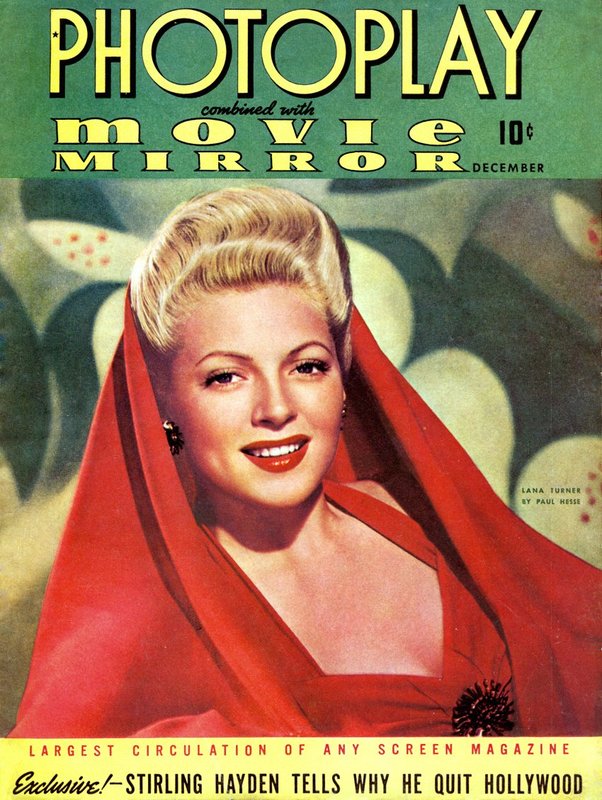

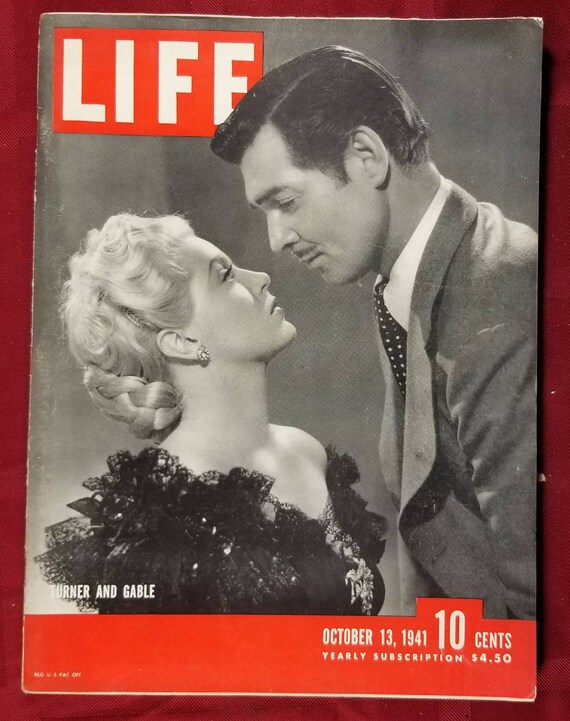

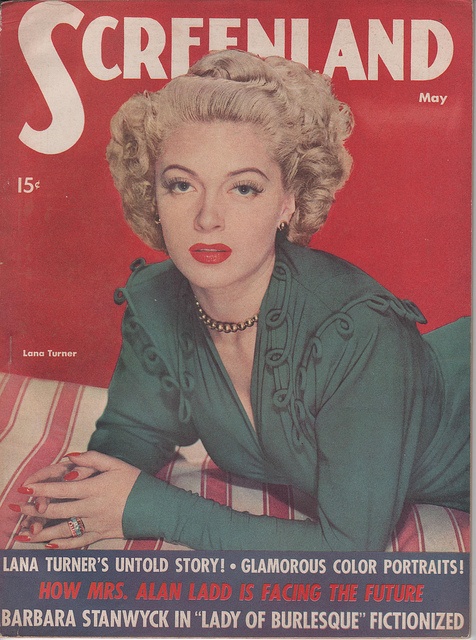

But the next year would see an upturn for Turner, with her breakthrough role in “Ziegfeld Girl” (1941). The lavish MGM A-picture, combining elements of Flo Ziegfeld’s famed live variety shows with behind-the-scenes drama and turmoil, had originally scripted Turner’s as a minor role among a cast that included Judy Garland, Jimmy Stewart and Hedy Lamarr. But someone had bigger plans for her: her character expanded as the shooting progressed, becoming the movie’s central arc, as she rises from driven material girl to star, loses her soul and hits the booze to fill the hole her material excesses and facile suitors can not. It-girl status, especially for one so young and vivacious, also made her a lightning rod in multiple senses. It drew her roles opposite Clark Gable, the studio’s top male draw, with whom she co-starred in “Honky Tonk” (1941) and “Somewhere I’ll Find You” (1942); the former notable for displaying Turner’s physical charms in revealing boudoir-wear, for which The New York Times’ review noted she was “not only beautifully but ruggedly constructed.”

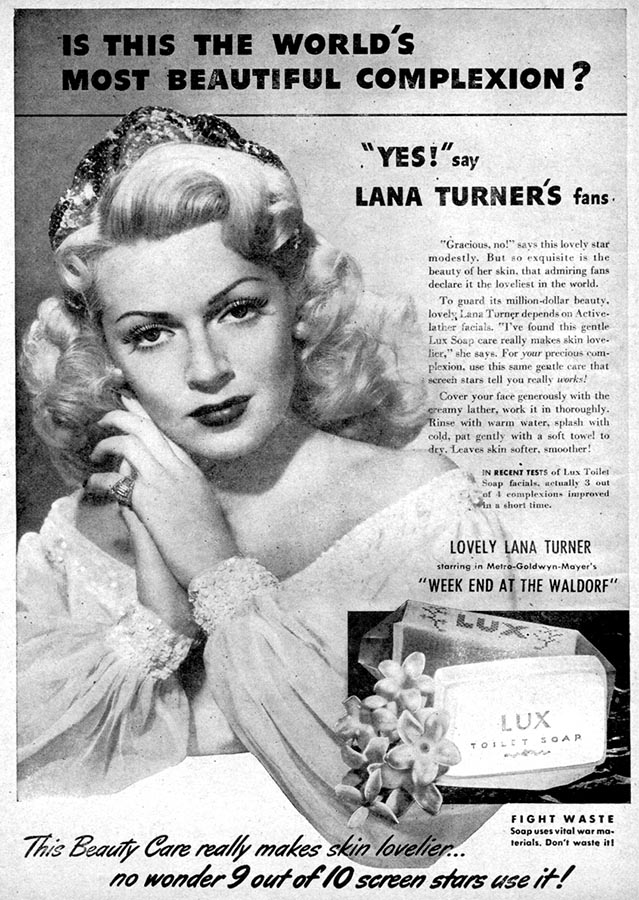

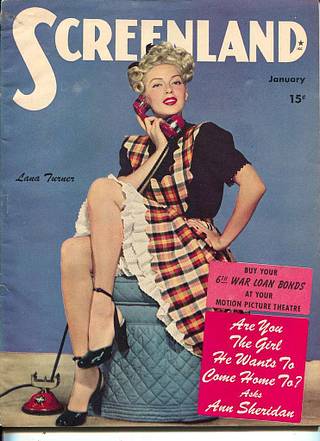

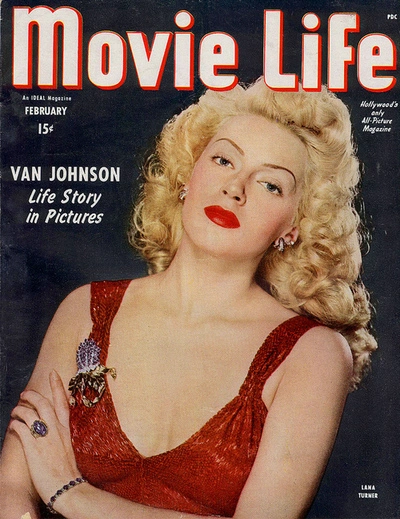

During the war years, MGM issued Turner’s pin-ups to remind G.I.’s the world over what they were fighting for, and she did her part by touring on behalf of the government’s “Buy War Bonds” campaign, offering a kiss to any man who bought bonds worth $50,000 or more. But every highlight seemed to cast a dark shadow for Turner. In LeRoy’s dark gangster thriller “Johnny Eager” (1942), her chemistry with leading man Robert Taylor essayed off camera, which may have prompted his real-life wife Barbara Stanwyck to attempt suicide and, at very least, led to Stanwyck refusing to speak to Turner for the rest of her life. In an effort to settle herself down, Turner married restaurateur Steve Crane in 1942, only to bumble into a bigamy dust-up the next year. Not long after the studio’s announcement that Turner was pregnant by Crane – she made the bubbly comedy “Slightly Dangerous” (1943) while in her first trimester – his previous wife cropped up to point out that their split was sealed by an “interlocutory decree,” meaning he had to wait a year before the divorce was final. Turner accused the woman of timing her move to blackmail the couple, ended up paying her hush money and secured an annulment. She and Crane separated, but the studio, and its potent publicity department feared the future box office potential of an unwed mother. Under MGM pressure, and with Crane suicidal, she agreed to remarry later in 1943 to give their newborn, Cheryl, a stable home. It would only last until August 1944.

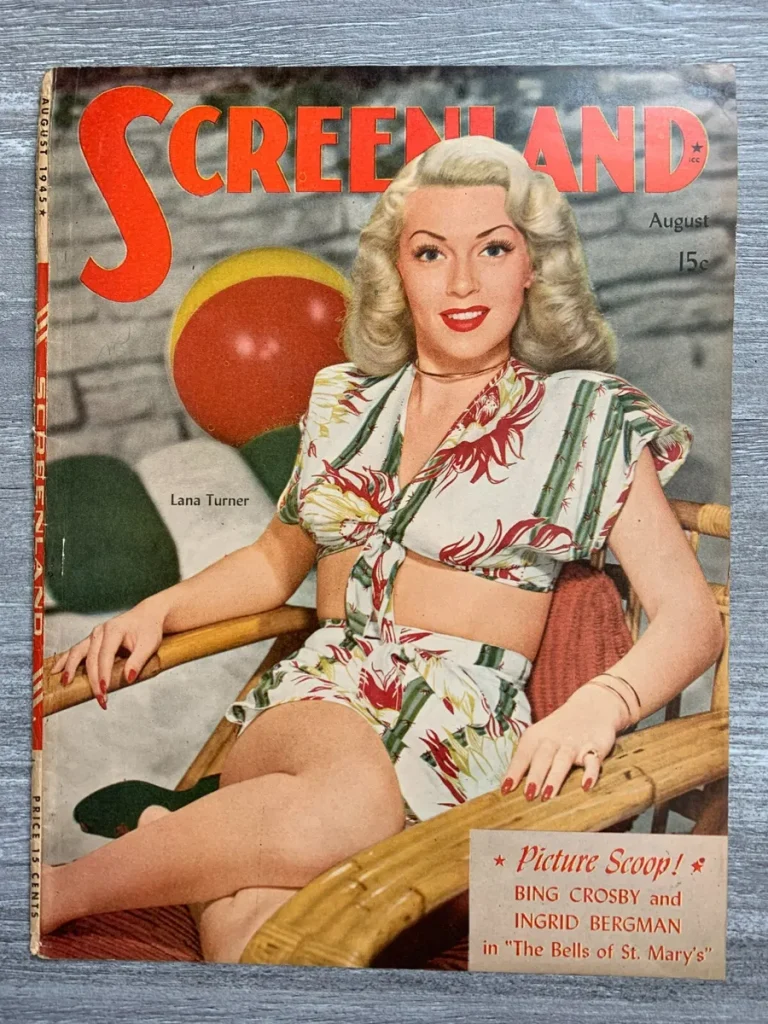

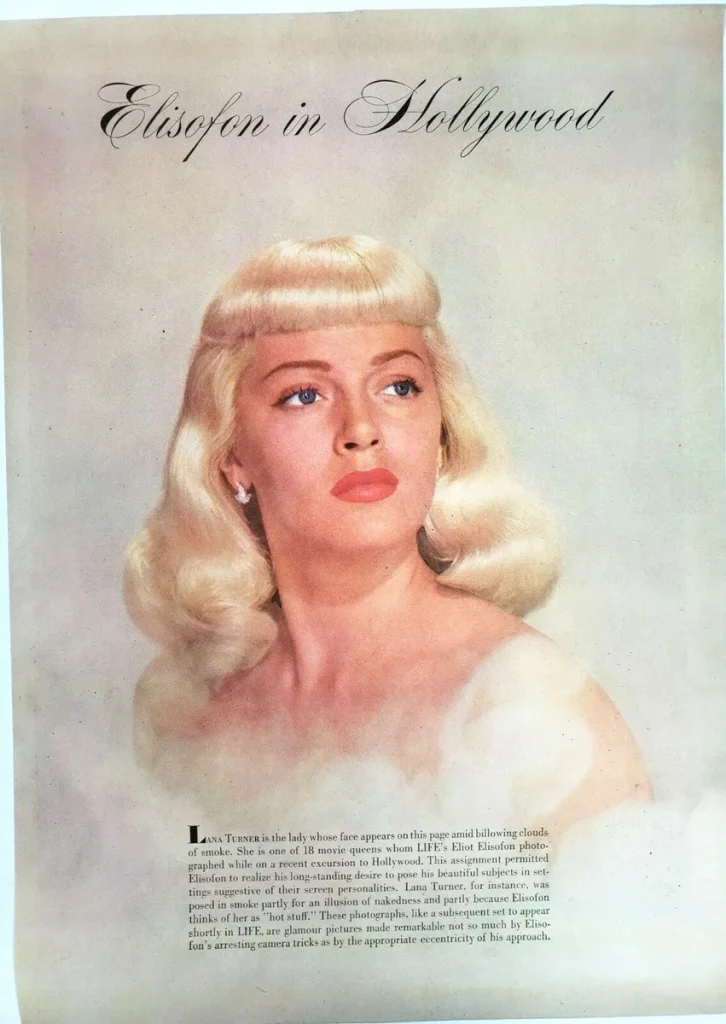

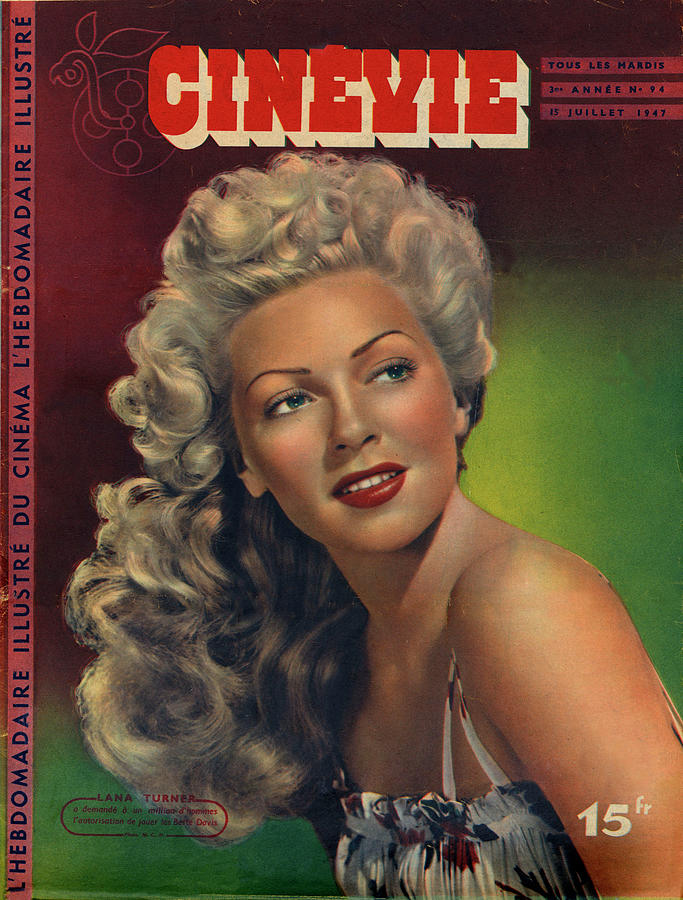

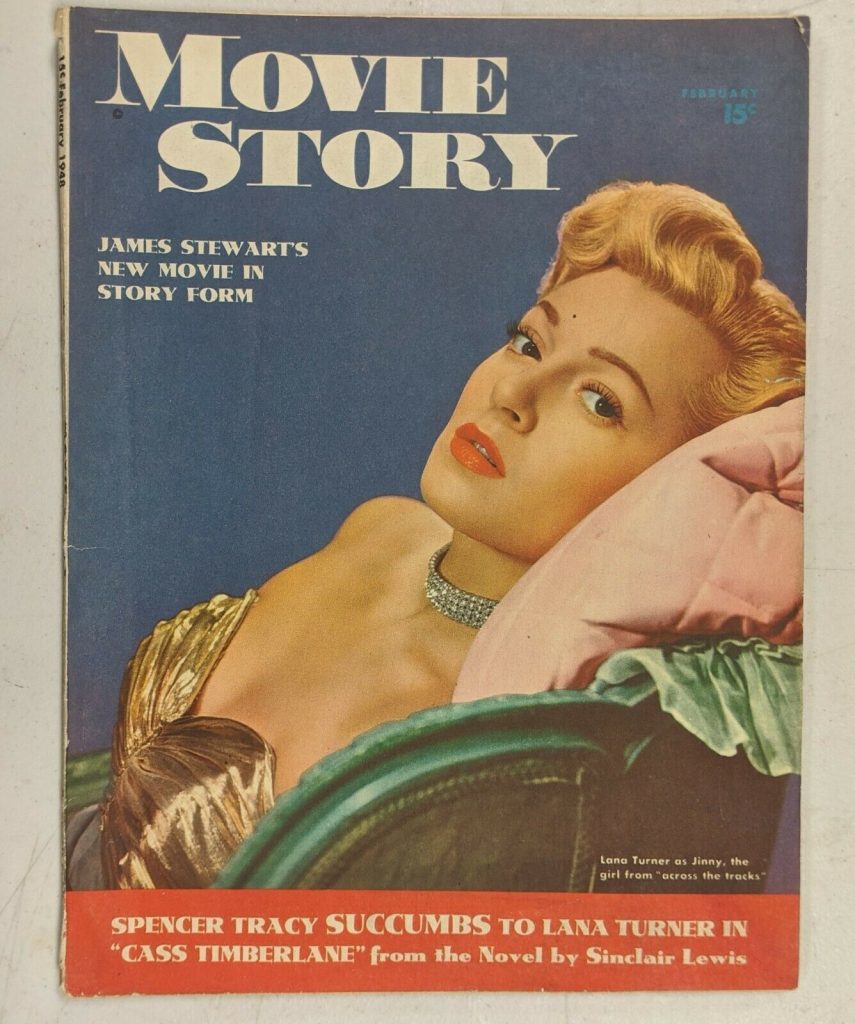

Even as her personal life remained stormy, her career began picking up steam. MGM re-upped her contract, paying her $4,000 a week starting in 1945, and, after biding her talents in series of humdrum projects, the studio brought in the script that gave her the chance to spread her wings artistically. Based on James M. Cain’s dark novel, “The Postman Always Rings Twice” (1946) would emblazon the newly platinum blonde as the femme fatale’s femme fatale. She played Cora, the unsatisfied wife of the owner of a roadside diner, who strikes up a fervent affair with a drifter (John Garfield), then a scheme by which the two will murder her husband. Even after significant dilution from the novel, the torrid on-screen relationship caused MGM execs such concern over the carnal heat between the stars that they directed the wardrobe department to dress her entirely in white outfits. The juxtaposition of this to the dark tenor of Cora’s desires and machinations had the opposite effect, and the movie opened to both critical laud and big box-offices receipts. Before “Postman,” Turner was a movie star, but after, critics welcomed her into rarified air. “One of the astonishing excellences of this picture is the performance to which Lana Turner has been inspired,” the New York World-Telegram raved. “[I]f it is possible not to be dazzled by that baby beauty and pile of taffy hair, you may agree that she is now beginning to roll in the annual actress’ sweepstakes.”

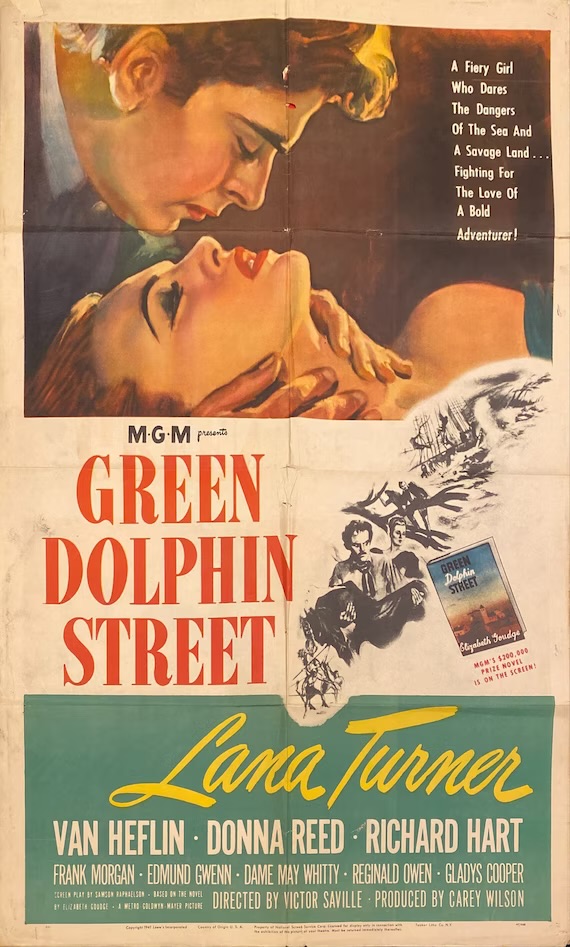

As she shot her next project, the period melodrama “Green Dolphin Street” (1947), Turner began a relationship with someone she would later consider the love of her life, leading man Tyrone Power – another headache for MGM spinmeisters, as Power was married. The coupling lasted a year and a half – with powerful Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper often taking snide shots at them. In early 1947, Turner found herself pregnant again, compounding the potential scandal until she had another abortion. Once Power finally obtained a divorce in 1948, he had struck up another relationship with actress Linda Christian and dumped Turner to marry her. Crushed, Turner’s sometime dalliance with young crooner Frank Sinatra briefly blossomed into an affair, hardly a relief to MGM management because Sinatra was himself married. Privately, however, Sinatra promised Turner to divorce his wife and they even began wedding plans, according to the memoir of one of Turner’s best friends in the trade, Ava Gardner, until either Sinatra, MGM management or a combination of both ended it. Turner, in turn, grudgingly acceded to dating a new suitor, thrice- and still-married millionaire gadabout Henry (“Bob”) Topping, Jr., an heir of the family who had founded the American Sheet and Tin Plate Co. (later to become a part of U.S. Steel). Though she admittedly felt no spark with him, one night at a swank hotspot, he dropped a diamond ring into her martini and she married him as soon as he had secured a divorce from his current wife.

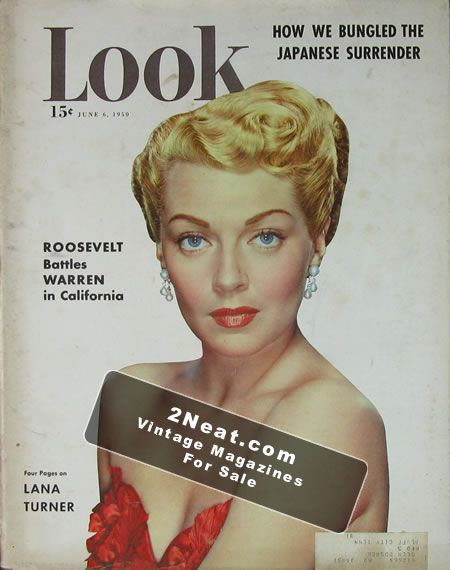

More ardor awaited her professionally, as well. She reunited with Gable and director LeRoy in “Homecoming” (1948) to give an impressive performance against type, starring as an unflappable, outspoken frontline nurse during World War I. In October 1948, she made her debut in Technicolor in the dazzling epic “The Three Musketeers” (1948), which framed her in the rich 17th century finery to stunning effect. She had originally bridled at the assignment for its heavy costuming elements so thus was briefly suspended by MGM, but her simmering turn as a villainess dropped jaws. The New York Times wagged. “Completely fantastic . . . is Miss Turner as the villainess, the ambitious Lady de Winter who d s the boudoir business for the boss. Loaded with blond hair and jewels, with twelve-gallon hats and ostrich plumes, and poured into her satin dresses with a good bit of Turner to spare, she walks through the palaces and salons with the air of a company-mannered Mae West.” After that last hurrah, however, the Sweater Girl’s career would falter and her psyche would enter a tailspin.

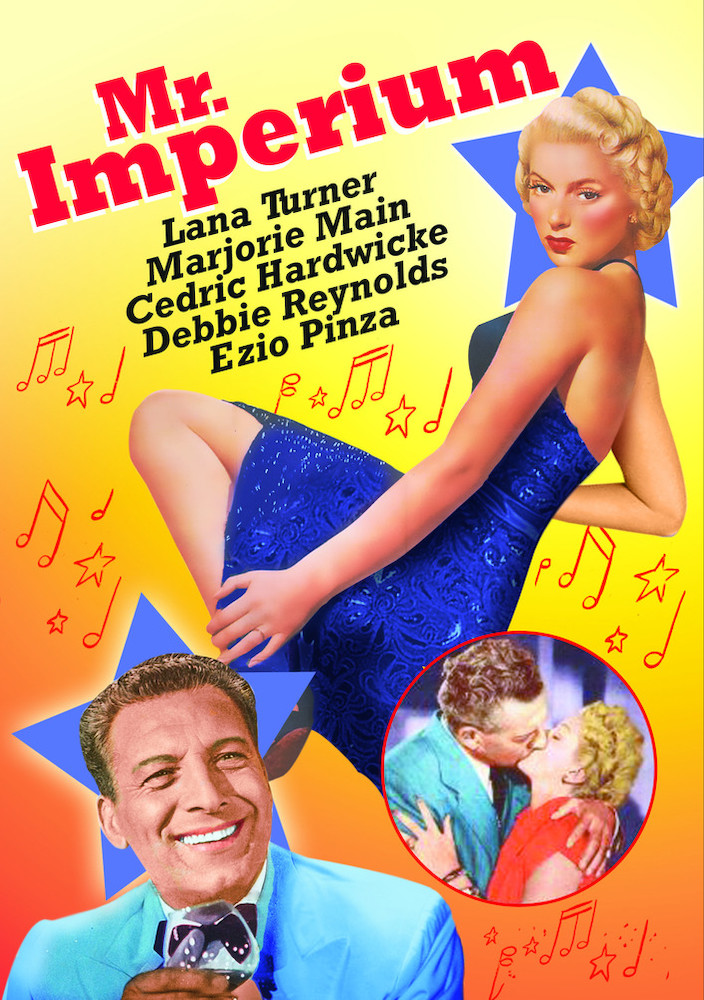

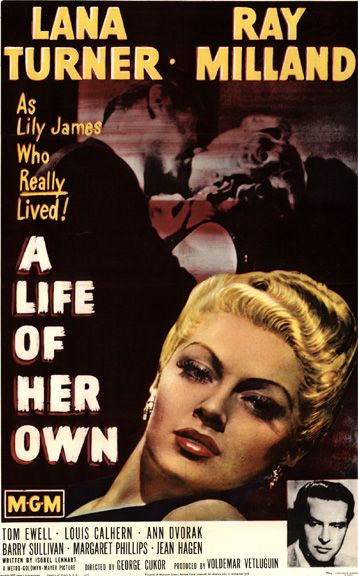

The Turner/Topping marriage would last longer than her previous unions, but it would not stem Turner’s private turmoil. Topping squandered his fortune on bad investments and gambling, even as Turner suffered two miscarriages, owing to an inherited genetic condition called RH incompatibility. The studio, meanwhile, turned a cold shoulder to her when she balked at doing more costumers. She returned to the screen in the soap operatic “A Life of Her Own” (1950), which became her first top-billed feature to be considered a box-office flop. Her next Technicolor outing did even worse – a lavish musical comedy that paired her with opera star Enzio Pinza, “Mr. Imperium” (1951), with Turner’s contribution to the musical aspect overdubbed. Depressed in the wake of the failure and now separated from Topping, she reached an emotional nadir, seeing her career as “a hollow success; a tissue of fantasies on film,” and began mulling a fatal sanction. She attempted suicide in September by slitting her wrists. Her death was prevented by her business manager Benton Cole, who broke down her bathroom door and got her to the hospital. Cole and MGM covered up the incident by telling the press Turner had accidentally fallen through the shower door.

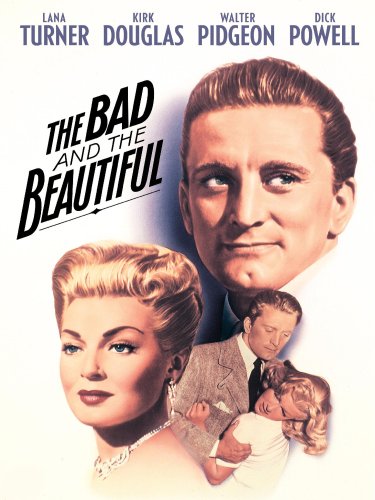

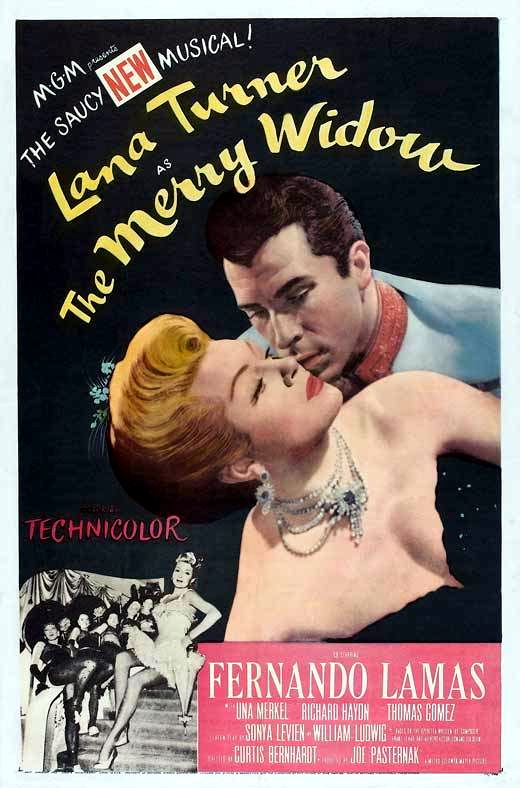

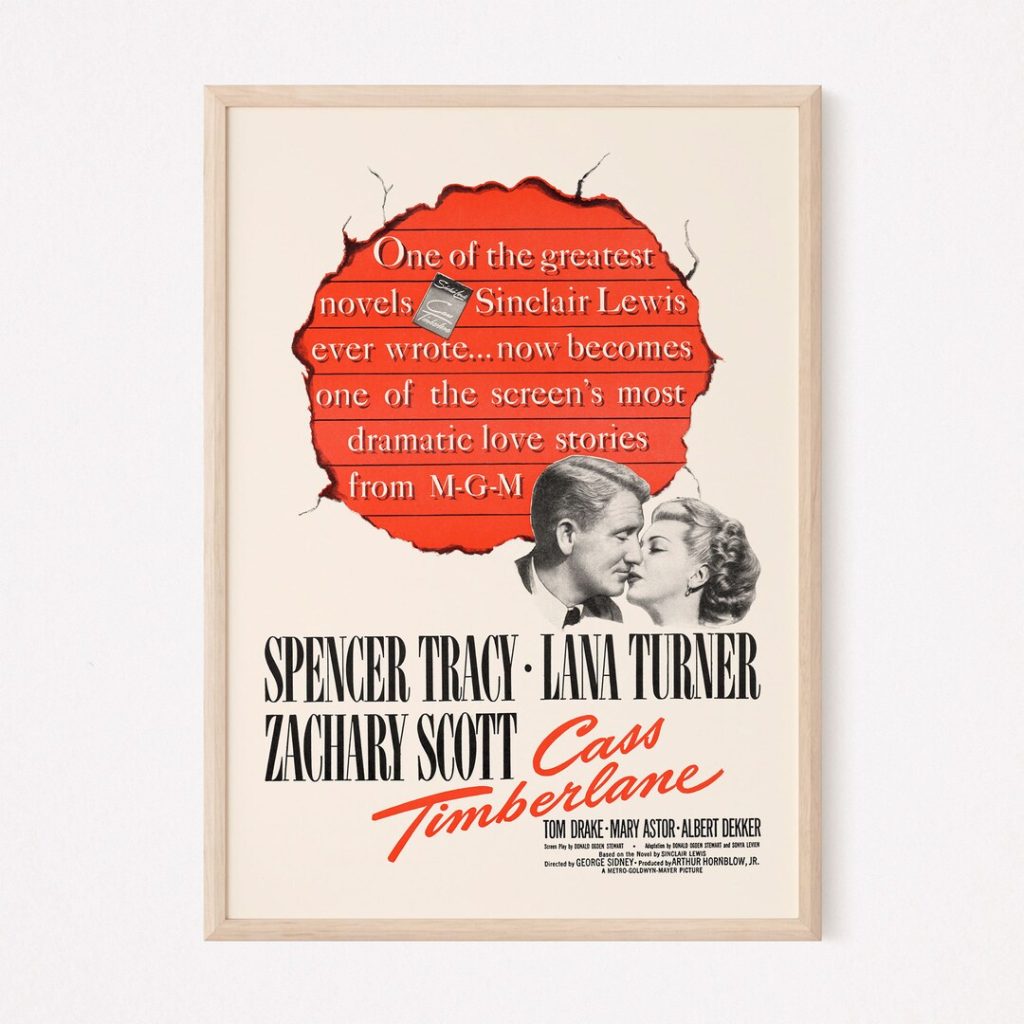

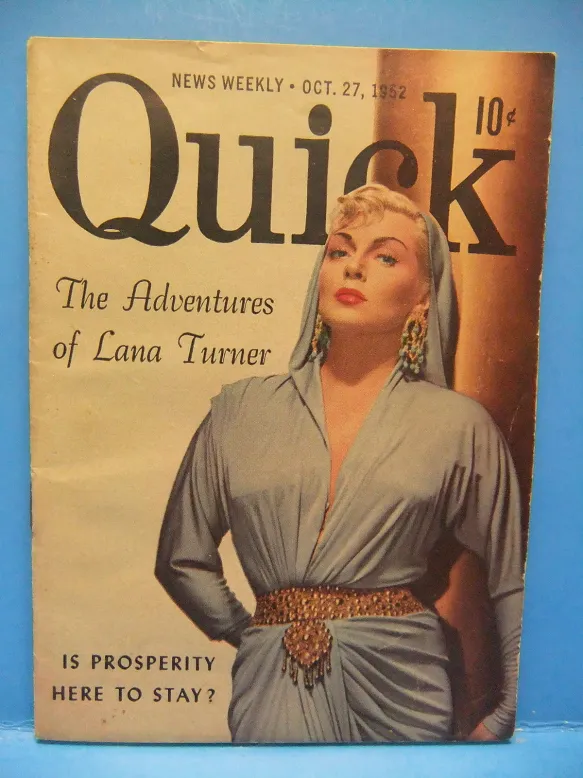

When she recovered, MGM put her back to work in a remake of “The Merry Widow” (1952), another opulent musical extravaganza requiring voice dubbing for her songs. When she and co-star Fernando Lamas tumbled into a real relationship, MGM’s publicity department made hay out of it. It proved such a potent combination that the studio began plotting another on-screen coupling, even as Turner went to work on “The Bad and the Beautiful” (1952), a sensationalized yarn promising to “expose” the unseemly inner workings of the industry – but she could little escape those herself. At a party thrown by William Randolph Hearst’s wife Marion Davies, Hollywood’s then-reigning “Tarzan,” Lex Barker, asked her to dance, and she acceded, stirring Lamas into a jealous rage. As she recounted it, when Barker escorted her back to the table, Lamas grumbled, “Why don’t you just take her out to the bushes and f*ck her.” After the proverbial scene, she demanded Lamas take her home, where an argument heated into a physical fight. A week later, when wardrobe fittings were to begin for “Latin Lovers” (1953), the still-bruised Turner brought the conflict to the attention of MGM exec Benny Thau, who immediately axed Lamas from the picture, replacing him with Ricardo Montalban. She finalized her divorce from Topping in December, in time for the big-ticket premiere of “The Bad and the Beautiful.” In the dark, sometimes overwrought melodrama, Turner played a boozy scion of a movie star family living in its shadow, who redeems herself as reinvented by conniving producer and lover Kirk Douglas, becoming a great actress, only to be dumped by Douglas for a younger up-and-comer. The movie hit big, earning six Oscar nominations and winning five, though Turner was spurned by the Academy for her role.

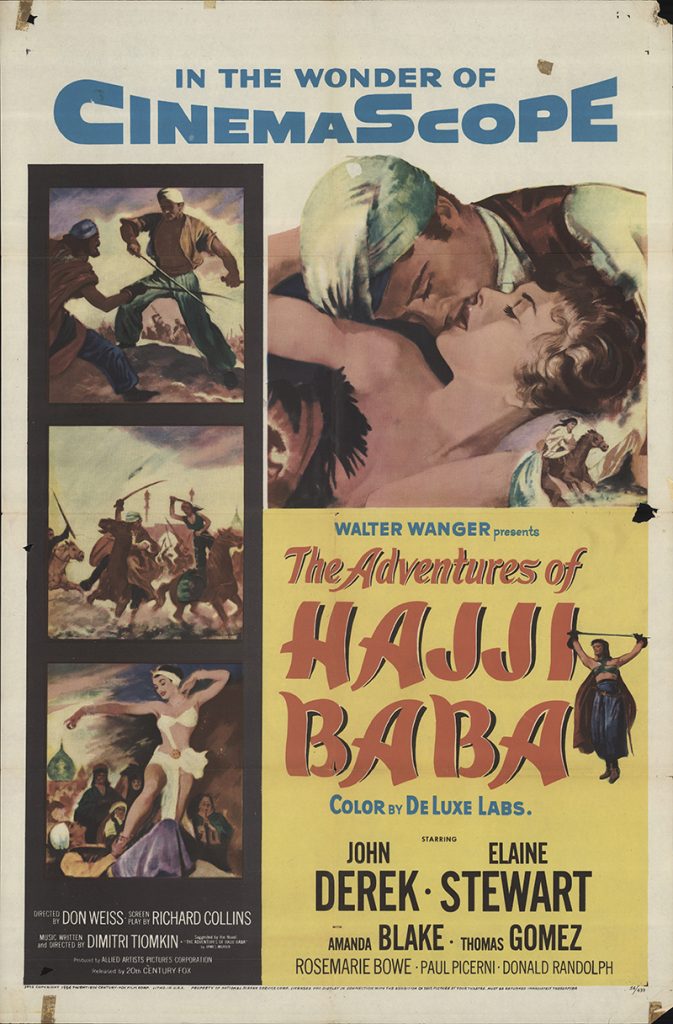

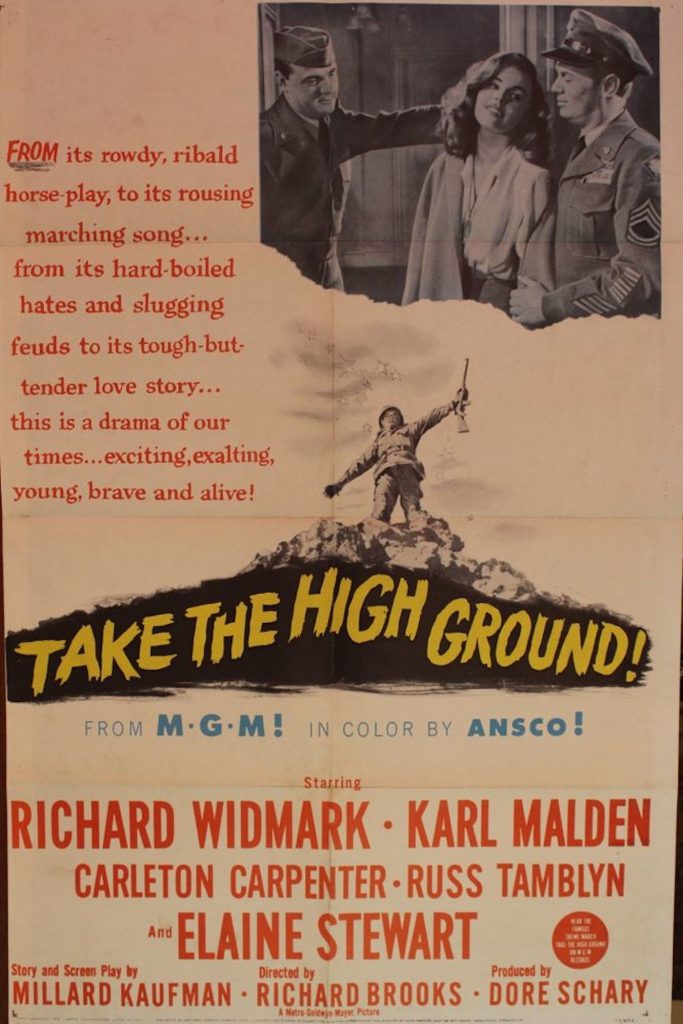

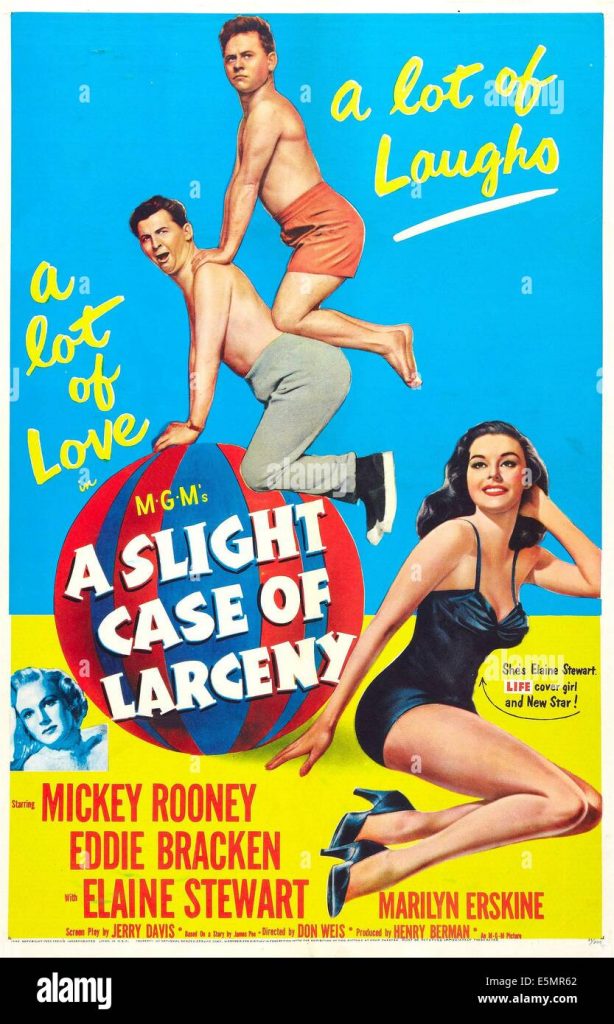

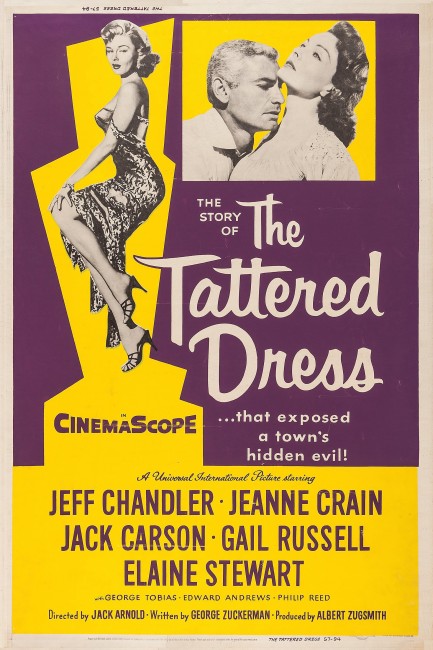

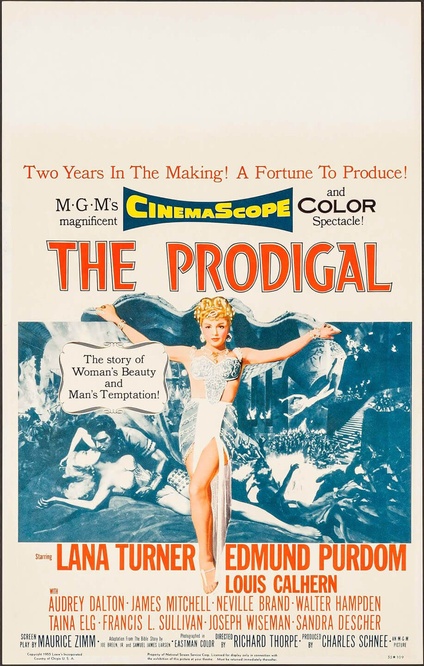

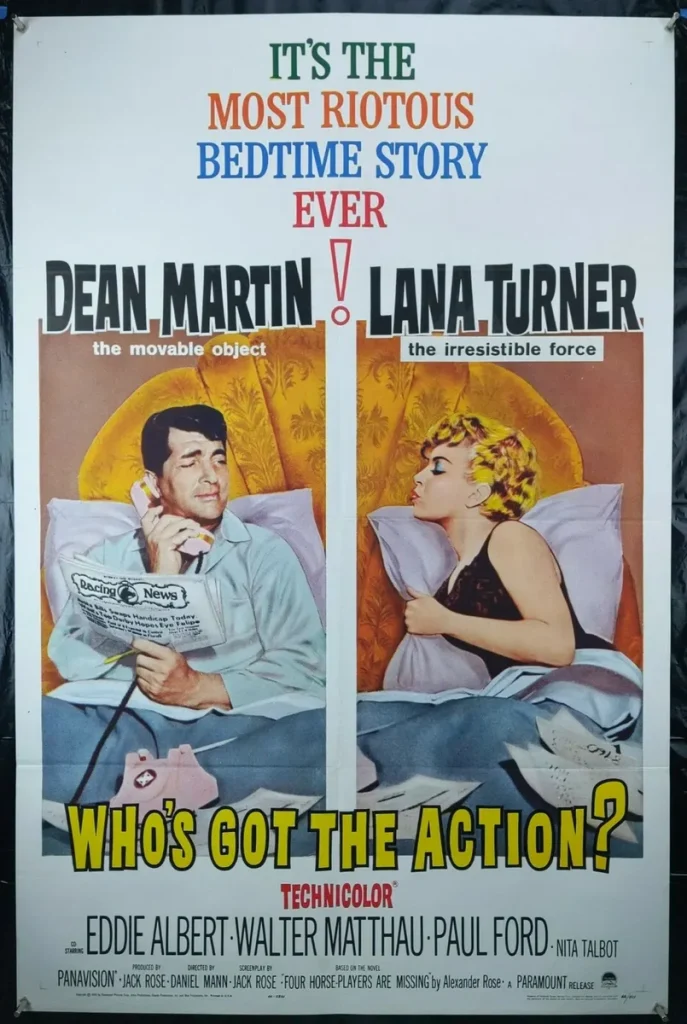

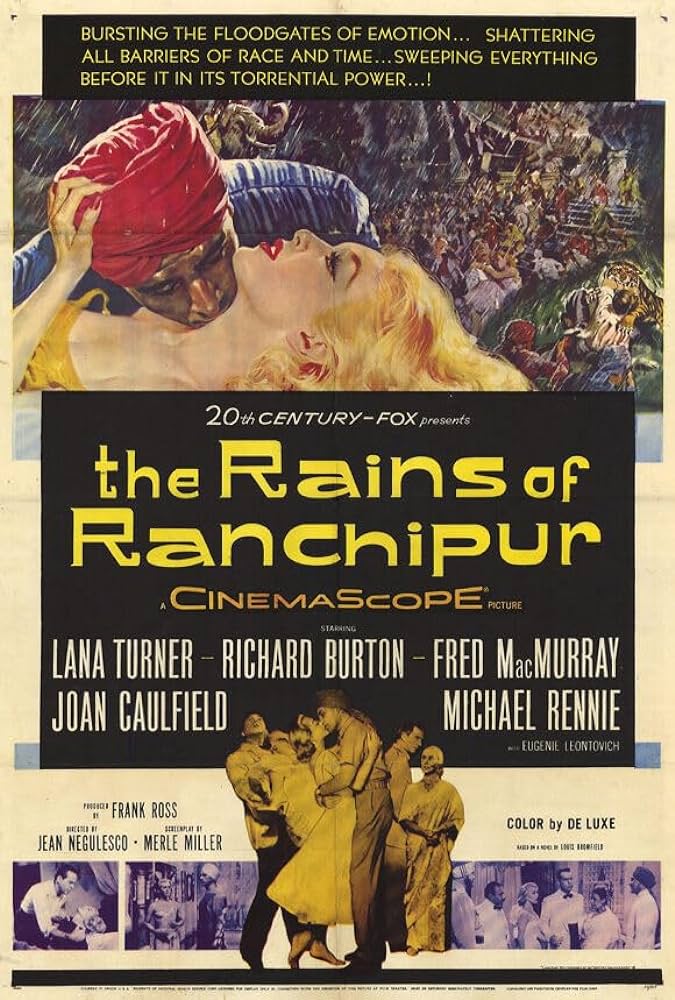

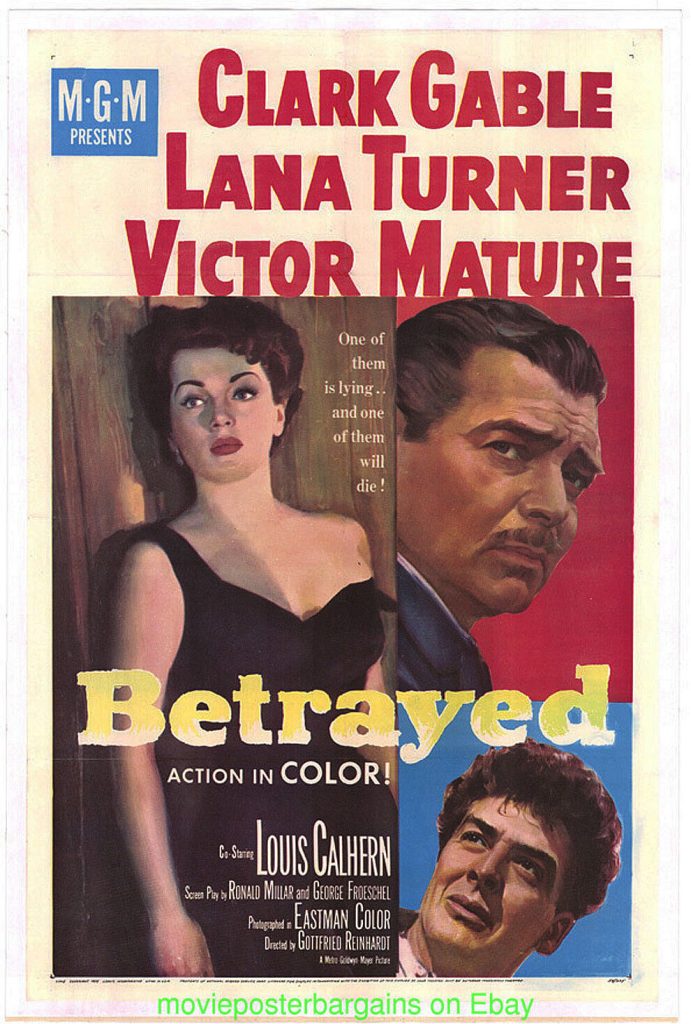

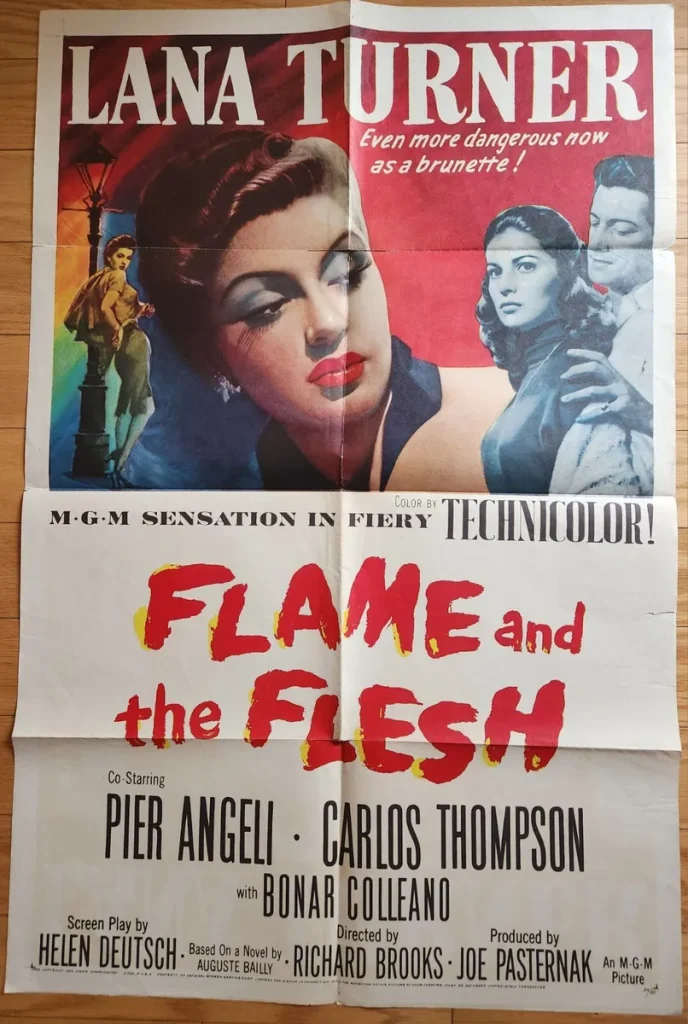

It would be the high watermark of her MGM years, as Mayer stepped aside for a new studio boss, Dore Schary, who thought little of Turner’s work and, some said, hoped to unchain the studio from her hefty contract. In the wake of the turnover, she took another regrettable leap into matrimony with Barker. Her whirligig game of romantic musical chairs did not go unremarked upon by her media nemesis, Hedda Hopper, who wrote in 1953 that, to Turner, “men are like new dresses, to be donned and doffed at her pleasure. Seeing a fellow that attracts her, she’s like a child looking at a new doll.” Turner and Barker wed in September 1953 and, dodging her nagging back-tax problem with the IRS, they took an extended European honeymoon on which she made two pictures, “The Flame and Flesh” (1954) in Italy and “Betrayed” (1954) in Holland; the latter her last film with Gable. Most notable of her remaining MGM films was a swords-and-sandals flick “The Prodigal” (1955), famous for seeing her bedecked in her most revealing costumes to date – a pagan “high priestess” role allowed wardrobe’s creativity to run wild – and for its becoming one of the most ambitious box-office flops of the decade. After a last respectable period costumer, “Diane” (1956), her home studio cut her loose, to her great relief.

As if by karma, she would earn her much-sought respect for her very next role, as 20th Century Fox came calling for a picture called “Peyton Place” (1957), which would assuage her yen for a simple, unglamorous dramatic part. But both before and after she made her memorable mark as beleaguered Constance MacKenzie, real life intruded, calling into question her own qualifications for motherhood. Turner’s daughter, Cheryl Crane, bided much of her early childhood in the care of her grandmother Mildred and in boarding schools, which afforded Lana the freedom to maintain her hobnobbing, club-hopping and paparazzi-posing regimen. Turner’s negligence towards her daughter had predictably not yielded a healthy relationship. Once, while at one of the exclusive boarding schools she attended in her youth, she had balked at standard routine of writing home to one’s parents, and a teacher told her she would get no dinner that night unless she wrote her mother. “Dear Mother,” she began the missive, “this is not a letter, this is a meal ticket . . .” Just 13 in 1957, Crane already showed she had inherited her mother’s beauty, but she harbored a horrific secret. In the spring of that year, she told her grandmother that her stepfather, Barker, had periodically raped and molested her since she was 10. Mildred called her daughter over to her house and had Cheryl tell the story, and, as Crane later told it, Lana went home, found Barker sleeping, took a gun from a bedside table and held it to his head. He awoke, and she simply said, “Get out.” According to Crane’s retelling of her mother’s account, Barker immediately protested that Cheryl had lied to her, but Turner had not mentioned her daughter. Their divorce became official in July.

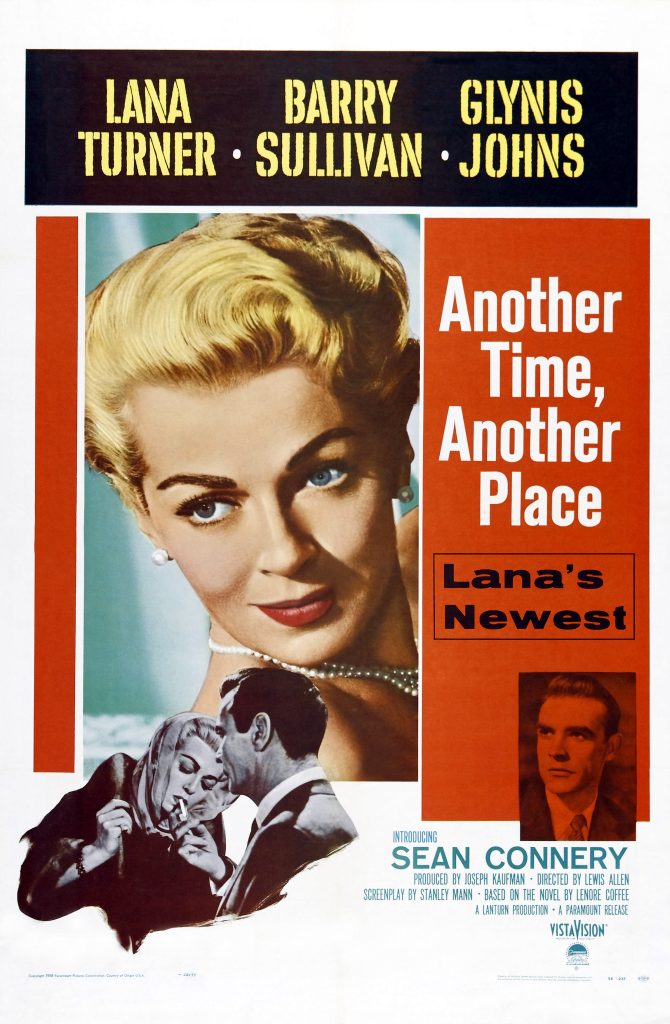

But Turner’s disastrous romantic inclinations and their affects on her troubled daughter, hardly ended there. On the rebound again, Turner took up with an admirer who had been pursuing her via gifts of flowers and music for a year or more – a proverbially tall, dark, handsome gift-shop manager named John Steele. While Steele and Turner dated, and as she spent much of that summer working on “Peyton Place,” he also took a paternal interest in Crane, giving her a horse and riding with her, even suggesting at one point that Turner send her away to board with his family in Woodstock, IL, to get the troubled teen into a more wholesome environment. When the relationship became public, friends intervened and told Lana who he really was – Johnny Stompanato, a smalltime hood and sometime bodyguard in the employ of L.A. mob boss, Mickey Cohen. At first, Turner recalled, she found herself titillated by the “forbidden fruit” aspect of the gangster connection, but Stompanato’s darker side would soon muddle that. He became discomfited at her refusal to be seen with him in public and, in October, she went to England to film “Another Time, Another Place” with a new leading man, strapping Scot Sean Connery, hoping to put some distance between her and Johnny “Stomp.” But she grew lonely in London, kept in touch with him with some overwrought love letters, and he soon flew to join her. Their reunion began amicably, but after a time, he insisted on coming to the studio over her objections and, when he heard a rumor of an affair between Turner and Connery, confronted Connery, pulled a pistol and menacingly warned him off. Connery, the story g s, snatched the gun away, decked Stompanato and personally kicked him off the set. Back in their hotel, Turner and Stompanato’s feuding escalated until he choked her severely enough that she found it difficult to speak for a few days, disrupting the production schedule. Turner responded by getting word to authorities that he had entered the U.K. under a passport falsely identifying him as John Steele, and Stompanato was deported.

Meanwhile, “Peyton Place” opened big in December. A standout in the ensemble melodrama, Turner became something wholly different; a frumpy, repressed woman in a repressed New England town riddled with secrets of avarice and amor. Turner’s climactic courtroom testimony, as she realizes that her attempts to keep reign on her teenaged daughter are only enabling the antisocial cycle, cinched her an Oscar nomination. She would learn about it, however, amid the resumption of her own nightmare. Instead of returning to L.A. after “Another Time” wrapped in early January, she decided to take a secret vacation in Acapulco. By some accounts, the conflicted Turner relented and invited Stompanato; by another, he used his mob connections to obtain her itinerary and stalked her to Mexico. Either way, their quarrels resumed there. He now began to threaten her, her mother and Cheryl if Turner dared leave him. At one point, she claimed, he even pulled a gun on her. When the news of her nomination by the Academy came, they returned to Los Angeles, where the press, Mildred and Cheryl awaited them. A wire photo taken of them at the homecoming only exacerbated matters when it circulated with the caption, “Lana Turner Returns with Mob Figure.” A conflicted Turner incomprehensibly continued to abide his company, even while deflecting his marriage proposals. She further enraged him by refusing to let him escort her to the Academy Awards gala on March 26. After the event, at which she lost to Joanne Woodward for her performance in “The Three Faces of Eve” (1957), she returned to the Bel Air Hotel to find him in a rage over being left out, and, according to her account, he beat her brutally. A week later, “the happening,” as she would later codify it, happened.

Johnny Stomp met his end on the night of April 4, 1958, Good Friday. With Cheryl, now 14, staying with Turner at the North Bedford house during her school’s Easter break, her mother told her, “This is it. I’m going to get rid of him. You stay in your room.” Crane tried to do homework, but she could not concentrate with the argument coming from her mother’s room. Crane went to the door and overheard Stompanato promising to menace Turner’s entire family, “making threats that he was going to cut her face, that he [was] going to kill my grandmother,” Crane recalled to Larry King in 2001. Crane ran down to the kitchen, found a carving knife and dashed back upstairs, calling to her mother to open the door. When Turner opened the door, Crane saw Stompanato behind her mother with his arm upraised, still shouting. Crane moved past her mother and thrust the knife into his abdomen. He collapsed. Turner, aghast, called her mother, who picked up their physician and rushed him over to the mansion. But it was too late. Cheryl had cut Stompanato’s aorta and he bled out. The doctor advised Turner call well-known defense lawyer-to-the-stars, Jerry Geisler, who contacted police. Beverly Hills police chief Clinton Anderson arrived to question Turner personally and said her first words to him were, “Can I take the blame for this horrible thing?”

The next morning and days after, newspapers ran crime scene photos of the dead Stompanato on front pages. Crane was kept in the county’s Juvenile Hall until a coroner’s inquest had ruled on the case. Mickey Cohen, who paid for Stompanato’s body to be shipped back to Illinois and for the subsequent funeral, publicly demanded murder charges against both Turner and Crane and, to embarrass them, released Turner’s sometimes steamy letters to the dead man to the press. The inquest convened a week later, media tumult engulfing it, with 120 seats of the 160 in the assigned courtroom claimed by the media, with ABC and CBS radio broadcasting live. Turner’s 62-minute testimony, interrupted periodically with bouts of sobbing, recounted the events and also delved into the abusive relationship with Stompanato – the violence she suffered and why she stayed with him to the point where circumstances so escalated. “Mr. Stompanato grabbed my arm, shook me,” she testified. “[He] said, as he told me before, no matter what I did or how I tried to get away he would never let me.” At a recess, surrounded by the press, she nearly fainted. At the conclusion of the inquest, the jury took less than a half hour to decide Stompanato’s death a justifiable homicide; that Crane had acted out of justifiable fear for her and her mother’s life. Though the verdict of a coroner’s inquest was not the final word on any case, it convinced the district attorney not to pursue charges against Crane. Mickey Cohen expressed outrage at the decision and Turner feared mob reprisals. Stompanato’s family in Illinois brought wrongful death suit, seeking $750,000 in damages from Turner and Steve Crane. Turner settled it for $20,000 in 1962. The DA did convene an inquiry to determine whether Turner was a fit mother, and Crane wound up tabbed a “ward of the court” and placed in the care of her grandmother.

As much as institutional Hollywood had already given Turner a pass on the sordid relationship and its violent end, the press proved less forgiving toward her as a mother. Hopper, echoing much of the media verdict – if more pointedly – called her “a hedonist without subtlety preoccupied with her design for living,” and declared that “Cheryl isn’t the juvenile delinquent; Lana is.” Crane’s difficulties did not end there. She became, as she later admitted, a “wild kid,” getting caught speeding, ending up in a reformatory, which she attempted to escape twice, landing in a mental institution and attempting suicide twice, all before she was 21. She began rebuilding her life with her father, helping to manage his restaurant, and eventually went into real estate.

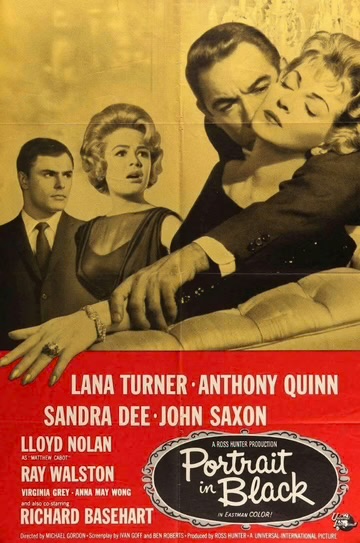

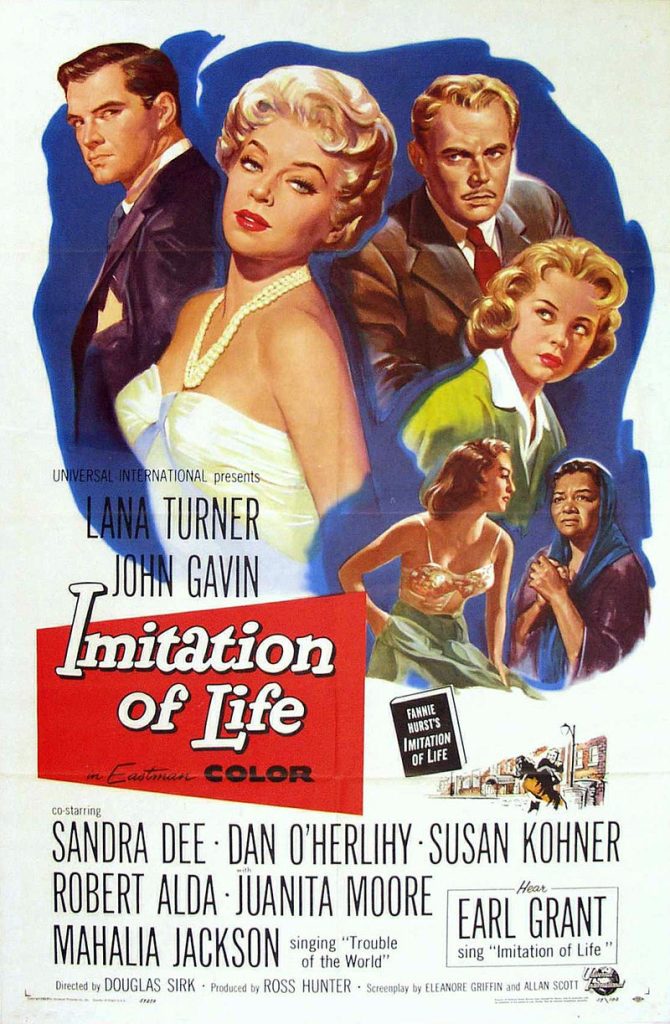

Cinematic fallout from “the happening” took on the distinct flavor of schadenfreude. The receipts for “Peyton Place” – still playing, with its ominously portentous courtroom scene – boomed again, and Paramount rushed “Another Time, Another Place” out for an early release. Turner attempted to rebound from the tragedy with another role that seemed close-to-home. Universal was remaking the tearjerker “Imitation of Life” (1959), and producer Ross Hunter cast her as a struggling actress who sacrifices her parental responsibilities in her drive to make it big, compromising her relationship with her rebellious teenage daughter (Sandra Dee). With the studio on the rocks at the time, it could muster only $250,000 for the budget, and Turner, in lieu of her usual pay, accepted a percentage of the film’s profits. It became the studio’s top grosser for the year, wracking up $50 million in revenues, salvaging the studio and earning Turner personally $2 million. Hunter brought her back the next year for “Portrait in Black,” a dark potboiler casting her as a scheming, cuckolding murderess, perhaps intended to revive her steam from “Postman” but unable to generate the same intensity, much less chemistry between her and co-star Anthony Quinn.

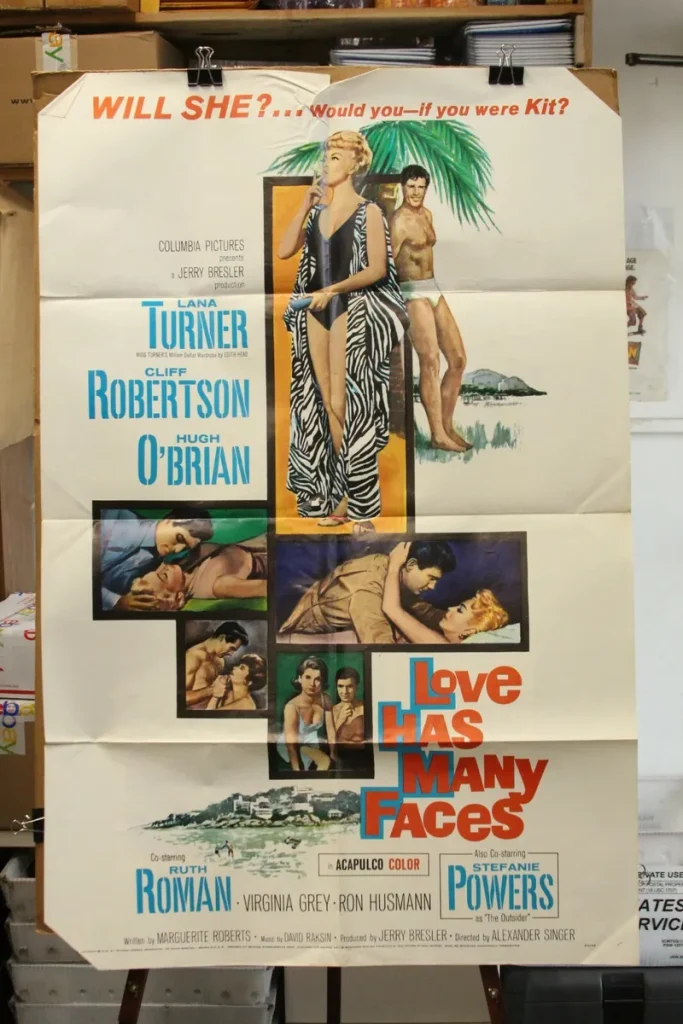

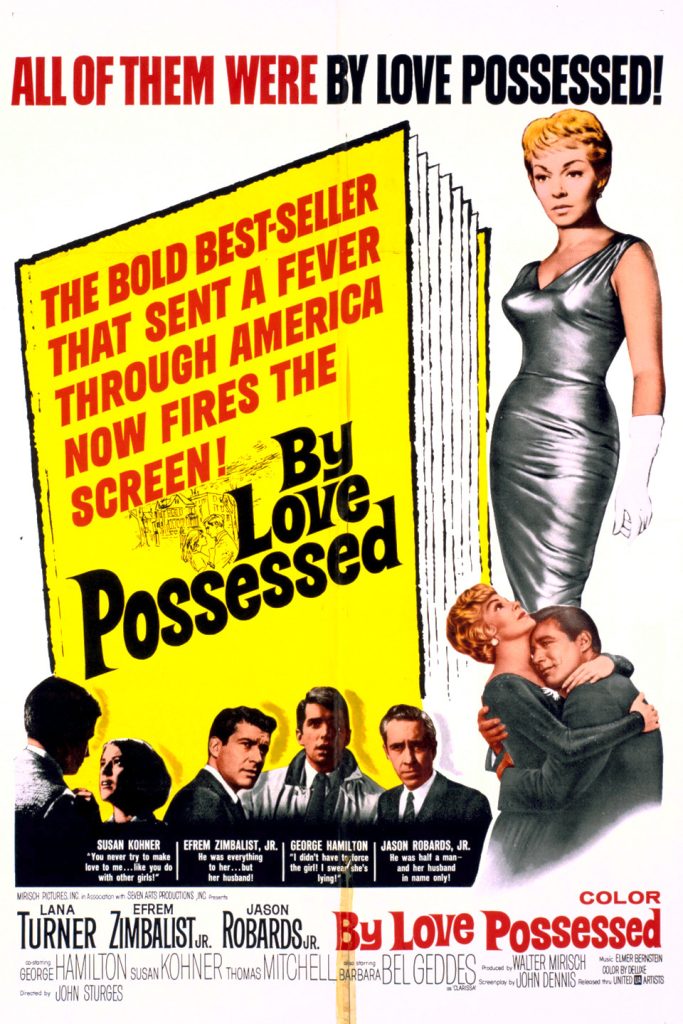

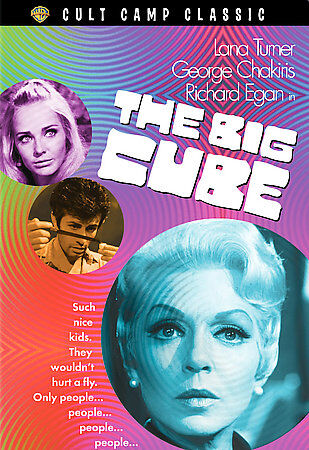

She found real chemistry, however, with Fred May, a wealthy rancher and member of the family that owned the May Co. department store chain, whom she made her 5th husband in November, seeking stability outside of Hollywood circles. It was not to be, they divorced in 1962, even as her films began to reflect her romantic success. In 1965, she married again, wedding the much younger Robert Eaton, and the next year appeared in her last real cinematic gem, “Madame X” (1966), again for Ross Hunter. Turner played the unsatisfied wife of a diplomat (John Forsyth) who starts an affair with a socialite (Ricardo Montalban), who is accidentally killed while she is with him. Under pressure from her domineering mother-in-law, she fakes her own death, flees the country to avoid a scandal that might sabotage her husband’s career, and spirals into a sordid life of alcohol abuse, prostitution and crime. Her character’s trial, and its creeping revelations of her true identity and even relationship to her defense attorney, evokes a riveting performance out of Turner, a symbolic, if not final, exclamation point on her career.

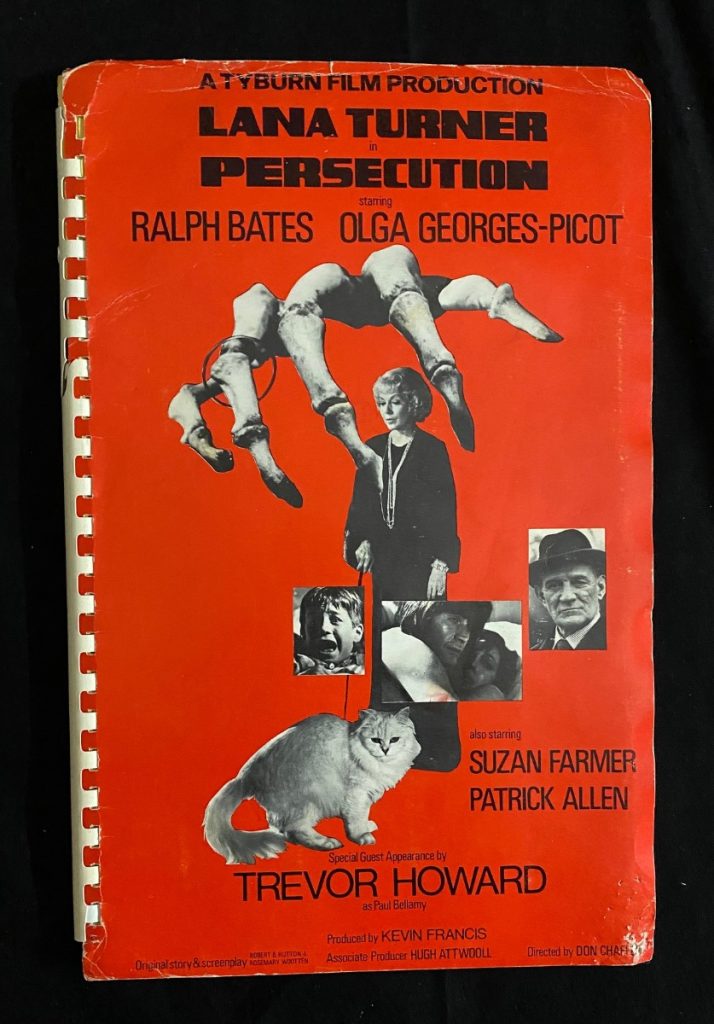

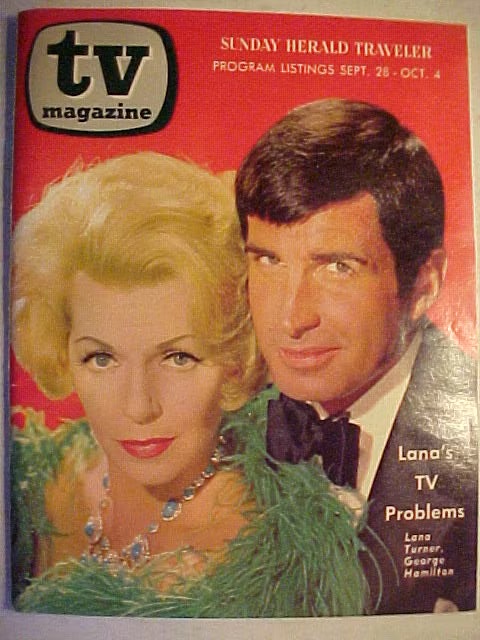

She divorced Eaton in 1969 after returning from entertaining U.S. troops in Vietnam and discovering preponderant evidence of his infidelities. She tried her hand at series television on would be a short-lived show, “The Survivors” (ABC, 1969-70), and, true to her lifelong insecurities, she was swept off her feet yet again by the oddest duck in her long roster of husbands, a lounge hypnotist, Ronald Pellar, stage-name Ronald Dante, whom she had met on the rebound in a nightclub. They married in May and, in late October, he simply disappeared out of her life. She wrote him a check for $35,000 for an investment, and a few days later, after Turner had given a speech at a San Francisco charity – and done so drunk, Pellar later claimed – he told her he was going out to get sandwiches and she never saw him again. In 1974, Pellar was later convicted of attempted murder in Tucson, AZ, for trying to contract a hit on a rival hypnotist, for which he served three and a half years in prison. Turner didn’t secure a divorce from Pellar until 1972.

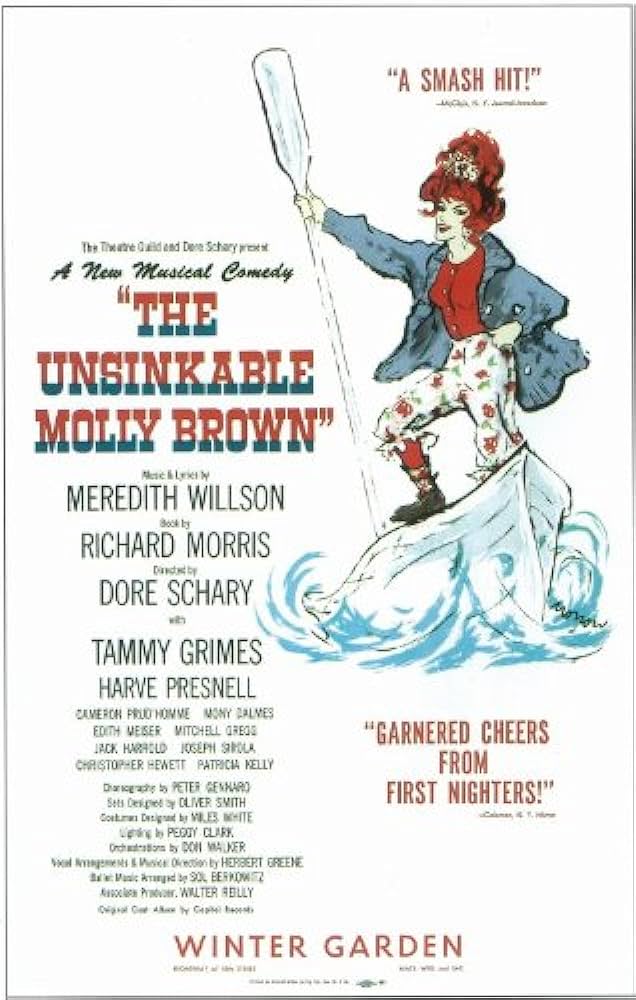

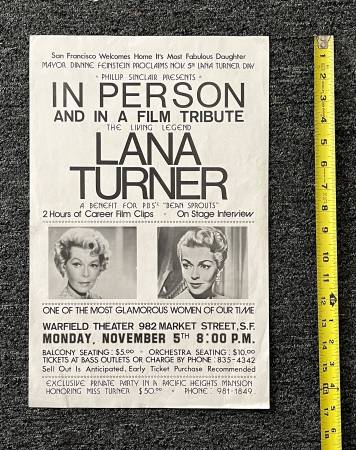

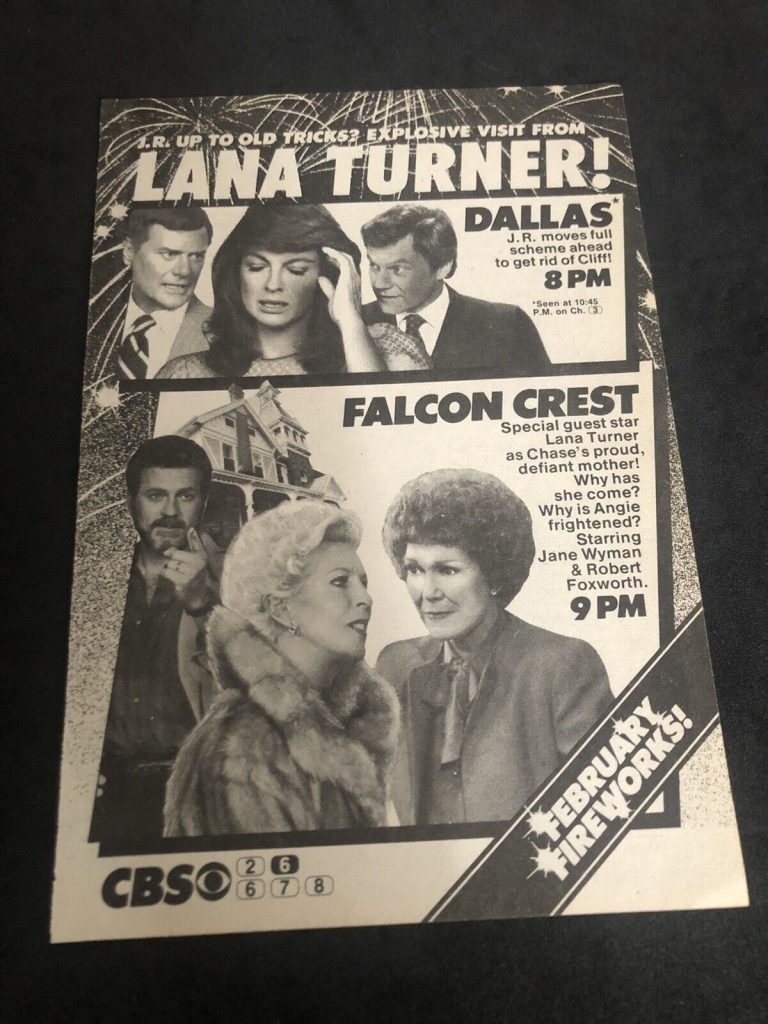

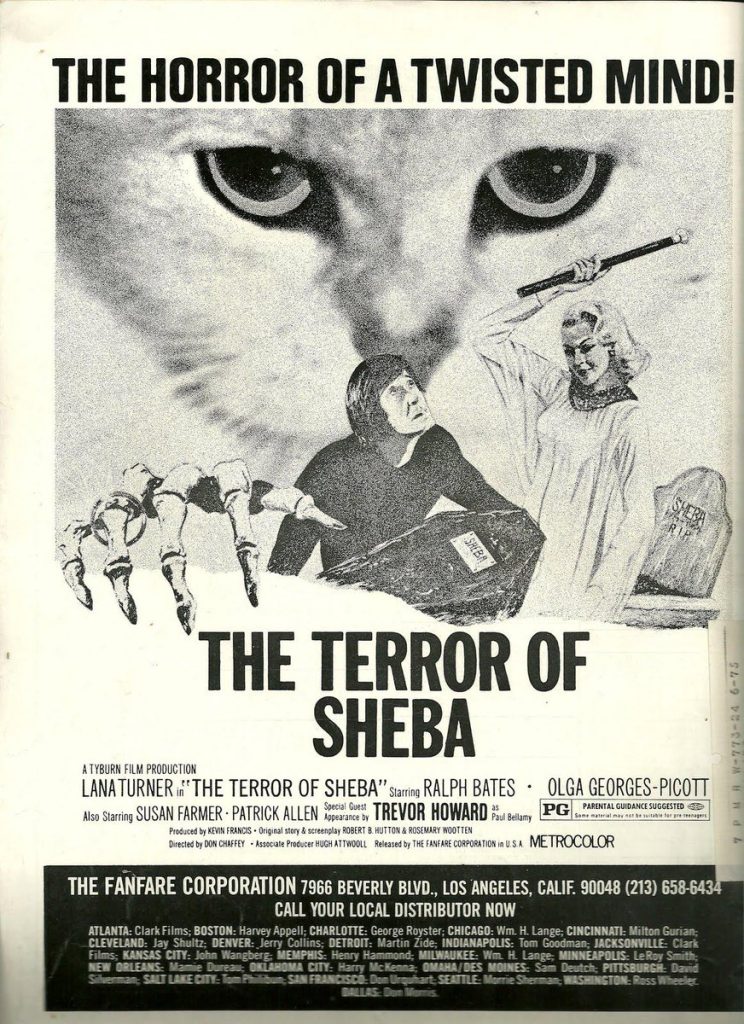

In the meantime, she had done her first theater work in “Forty Carats” on Broadway, before touring with the production. She returned to TV periodically, landing some guest shots on “The Love Boat” (ABC,1977-1984) and most famously, playing a conniving matron in combat with the show’s star, Jane Wyman, in the nighttime soap opera “Falcon Crest” (CBS, 1981-90) during its 1982-83 season. The latter coincided with the publication of her autobiography, Lana: The Lady, The Legend, The Truth, as well as an homage to her by her late-career manager Taylor Pero, Always Lana. In 1988, Cheryl Crane published her own memoir, Detour, in which she claimed she had reconciled with her mother in 1981 and established a friendship at long last.

The above TCM Overview can also be accessed online here.

.