Clint Walker obituary in “The Hollywood Reporter” in 2018.

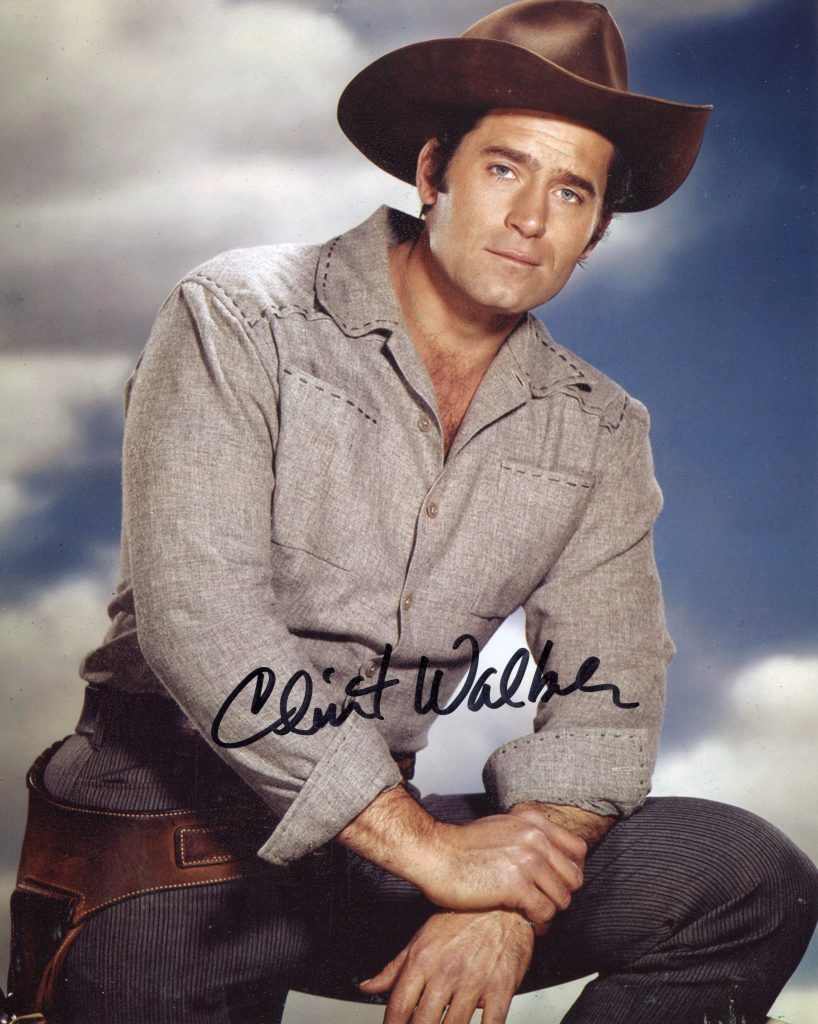

Clint Walker, who flexed his considerable brawn — but only when he had to — as a gentle giant on Cheyenne, the landmark 1950s Western that aired for seven seasons on ABC, has died. He was 90.

Walker, who also starred in such films as Send Me No Flowers (1964), None But the Brave (1965) and the World War II classic The Dirty Dozen (1967), died Monday of congestive heart failure in Grass Valley, California, his daughter Valerie said. !

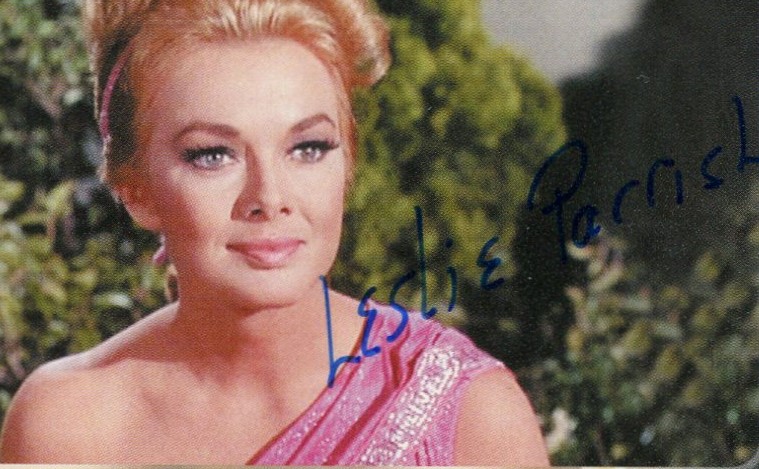

With a chiseled 6-foot-6, 250-pound physique that showed off a 48-inch chest and 32-inch waist, the rugged, blue-eyed Walker was often hired for Westerns and action work. He was tough (and lucky) off the screen as well: He survived a 1971 skiing accident at Mammoth Mountain in California in which his heart was punctured by a ski pole and he was pronounced dead.

In 1955, Walker was cast by Warner Bros. in TV’s first-ever hourlong Western as Cheyenne Bodie, a principled cowboy drifter in the post-American Civil War era who was raised by the Cherokees who killed his parents. Cheyenne, produced by Roy Huggins of Maverick and Rockford Files fame, started out as part of Warner Brothers Presents in a rotation with the movie spinoffs Casablanca and Kings Row.

“I think they had all the leading men available in Hollywood to test for Cheyenne two days in a row, and they had me test with them,” Walker recalled in a 2012 interview for the Archive of American Television. “The first day I was very, very nervous. I could see all these people that I’d seen in pictures over the years and I thought, ‘I don’t stand a chance.’

“The second day, I thought, ‘I’m not going to get the job anyway so why don’t I just relax and enjoy it,’ which I did. Then the next thing I heard about four days later was Jack Warner reviewed all the stuff, pointed to me and said, ‘That is Cheyenne.'”SEE MOREBig Screen Giants: The 11 Tallest Movie Stars Ever

In 1958, Walker, now a household name, went on strike in a contract dispute, and while he was away, Warners replaced him with Ty Hardin as a character named Bronco Layne. When Walker returned to the series in 1959 after his deal was renegotiated, Hardin was given his own show. Cheyenne ran for 103 episodes until December 1962.

Walker, a baritone, also sang on Cheyenne, and the studio produced a 1959 album, Inspiration, with Walker and the Sunset Serenades performing traditional songs and ballads.

Norman Eugene Walker, a twin, was born May 30, 1927, in Hartford, Illinois. He fashioned his own weights out of concrete, joined the Merchant Marine at age 17 and toiled on a riverboat, in a paper mill and on an oil field. Working security at the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas, he met show-business types who encouraged him to try his luck in Hollywood.

Not surprisingly, Walker’s first role came as an uncredited Tarzan in the Bowery Boys film Jungle Gents (1954).

He heard Cecil B. DeMille was looking for muscular men to cast for his 1956 epic The Ten Commandments. Walker got an appointment with the intimidating director, but on the way to Paramount, he stopped on the freeway to change a flat tire for a woman.

“You’re late, young man,” Walker recalled DeMille saying when he arrived. When he told the director the reason why, DeMille replied, “Yes, I know all about it. That [woman you helped] was my secretary.”

Walker got a small part in the picture.

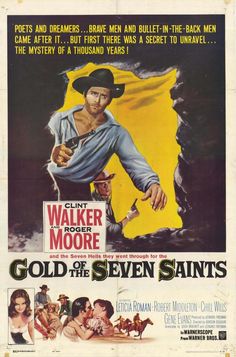

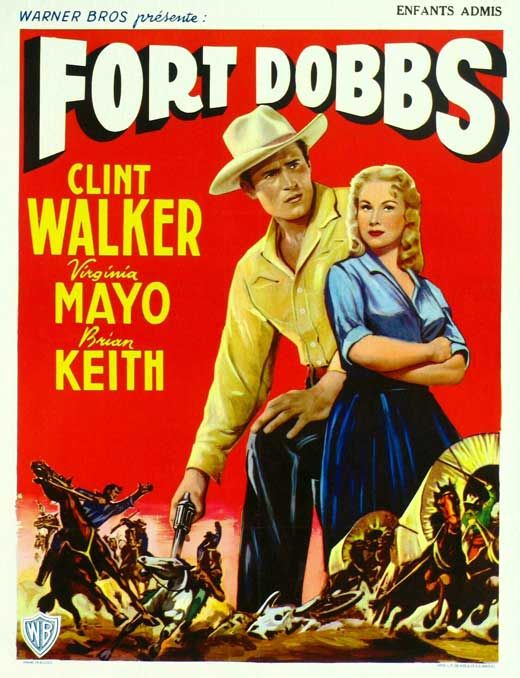

After Cheyenne got hot, he starred in the title role of Yellowstone Kelly (1959), playing a fur trapper who because of his friendship with the Sioux refuses to join with the U.S. Cavalry in a 1876 raid against the tribe. That movie was sandwiched between the Westerns Fort Dobbs (1958) and Gold of the Seven Saints (1961).

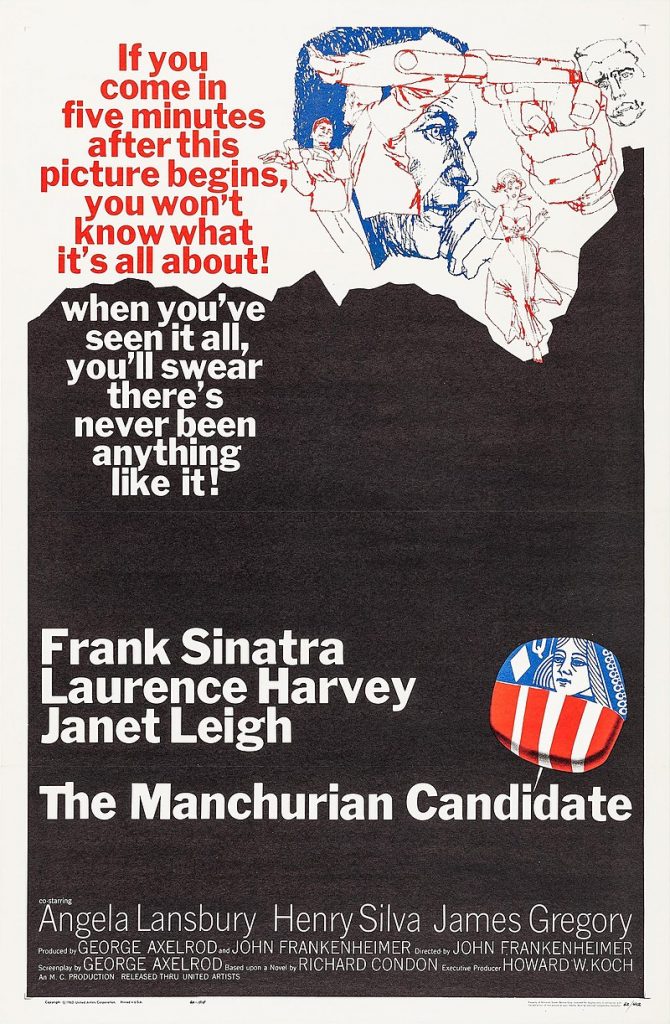

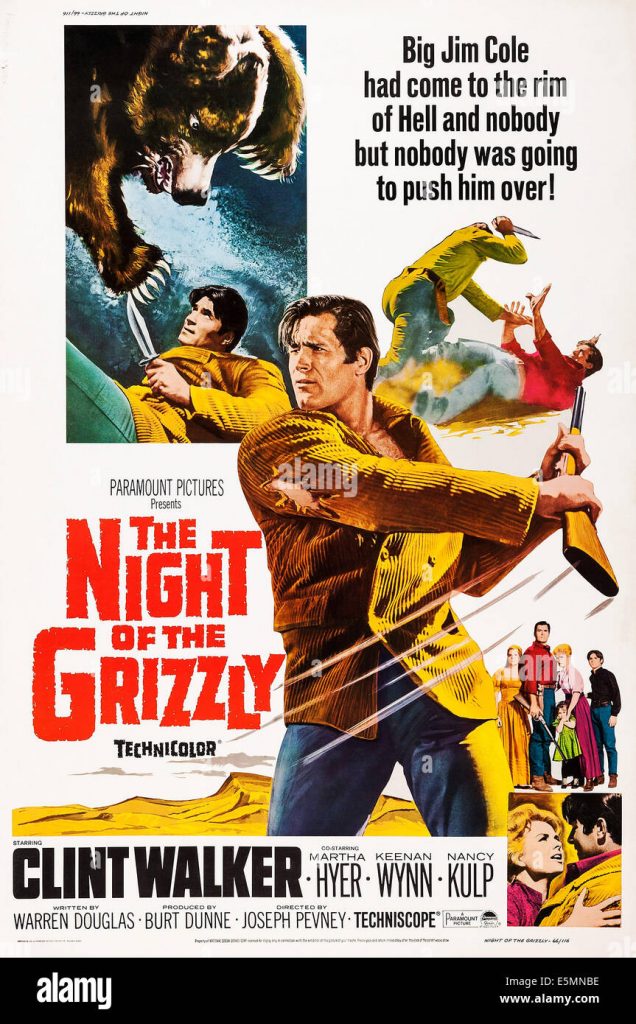

Walker received second billing to Frank Sinatra in None But the Brave, a World War II saga set in the South Pacific that Sinatra also directed. Walker then starred as Big Jim Cole in the adventure movie The Night of the Grizzly (1966), which he said was his favorite film to do.

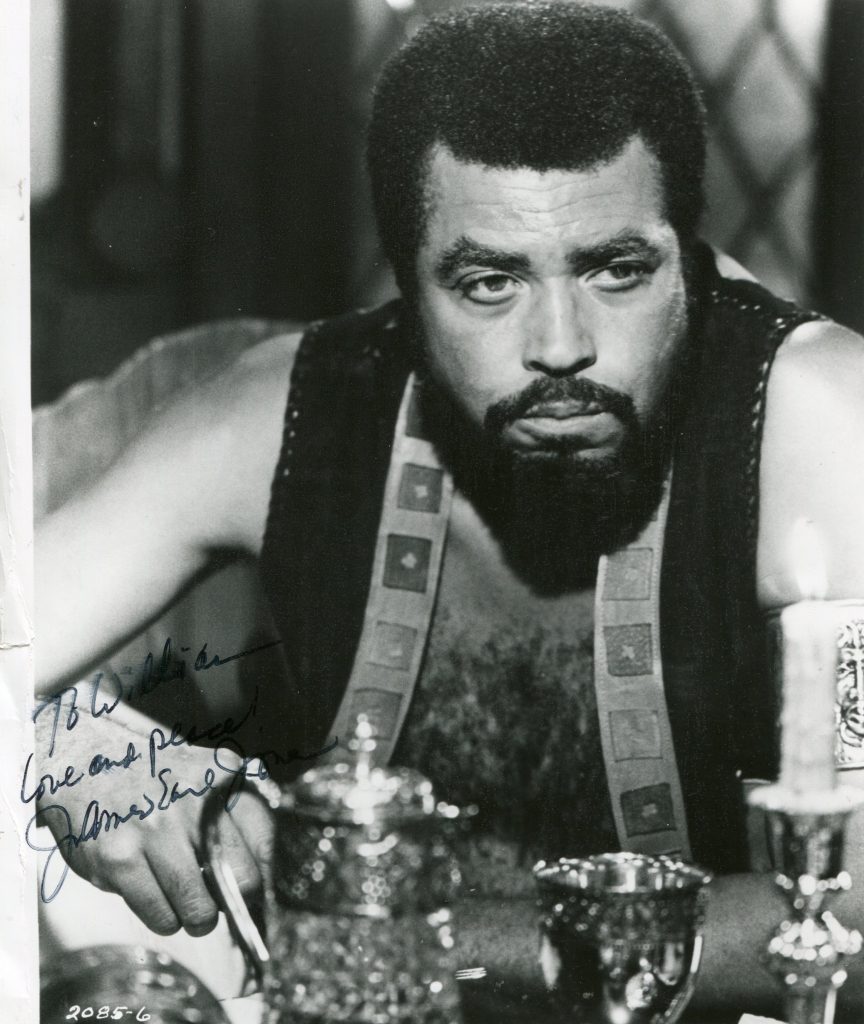

The big man hit his stride with The Dirty Dozen, which starred Lee Marvin as a hardscrabble officer stuck with the dirty duty of penetrating a German fortress, accompanied by 12 condemned soldiers who have nothing to lose. Walker played Samson Posey, who had been convicted of murder. In his best scene, Marvin goads Walker into flashing his temper, attacking him with a knife before disarming the much bigger guy.

(Years later, Walker lent his authoritative voice to the role of Nick Nitro in Joe Dante’s 1998 animated film Small Soldiers. Dirty Dozen co-stars Ernest Borgnine, Jim Brown and George Kennedy also had roles.)

The good-natured Walker also appeared in much frothier entertainment, most notably in the light comedy Send Me No Flowers (1964) with Rock Hudson, Doris Day and Tony Randall.

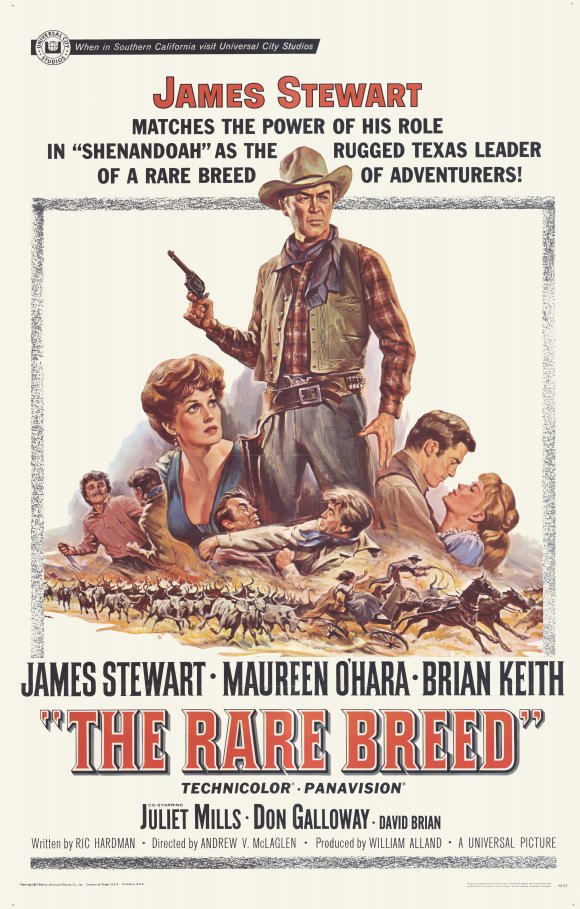

He continued to work steadily late in 1960s with roles in Sam Whiskey, More Dead Than Alive and The Great Bank Robbery, all released in 1969. He co-starred in The White Buffalo (1977), one of the quirkiest Westerns ever made, in which Charles Bronson limned Wild Bill Hickok in pursuit of an albino buffalo.

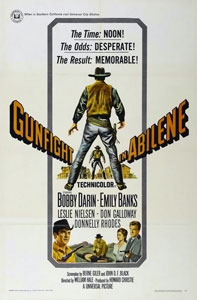

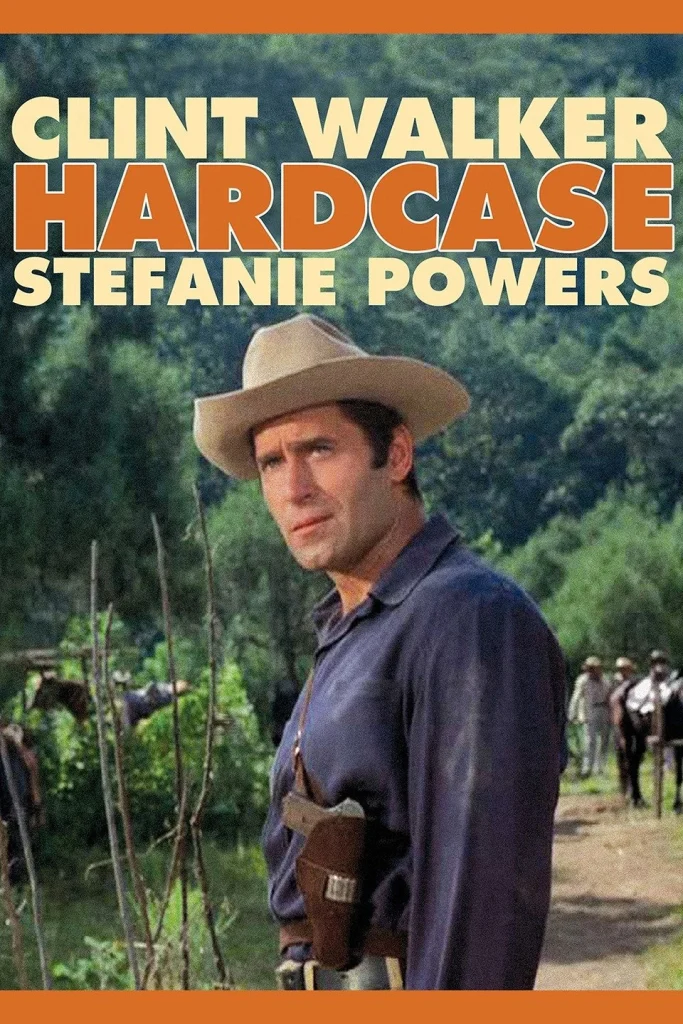

During the 1970s, Walker was seen in the telefilms Yuma from Aaron Spelling, Hardcase and The Bounty Man and in Pancho Villa (1972). He starred in a shortlived Alaska-set series titled Kodiak, in which he played the title character, an Alaska State trooper.

Walker made numerous guest-star appearances on a wide range of TV shows during his career, including on The Jack Benny Program, Maverick, The Lucille Ball Show and Kung Fu: The Legend Continues.

Duane Byrge contributed to this report.

The Times obituary in 2018.

Having heard that Cecil B DeMille was looking for muscular actors to cast for his biblical epic The Ten Commandments, Clint Walker was on his way to audition for the famously intimidating Hollywood director in 1955 when he spotted a woman standing by a stranded car on the side of the freeway.

Although he was an unknown aspirant on his way to an appointment that he hoped would land him his big break in the world of films, he gallantly stopped to change her burst tyre. When Walker eventually arrived at the Paramount studio, considerably less presentable than when he had set out, DeMille looked him up and down. “You’re late, young man,” he said sternly.

Fearing that his career was over before it had started, Walker desperately began to explain the cause of his delay, only for the director to cut him short. “Yes, I know all about that,” he said. “It was my secretary.”

DeMille cast Walker as the captain of the guard to the Pharaoh Rameses, played by Yul Brynner. It was his first credited part and led in the same year to his best-known role, as the lead character in the pioneering TV western Cheyenne. Walker played Cheyenne Bodie, a rugged yet big-hearted cowboy drifter who fought baddies and dished out frontier justice.

He got the part over a number of more famous actors. “They had all the leading men available in Hollywood to test for Cheyenne two days in a row,” he recalled. “The first day I was very nervous. I could see all these people that I’d seen in pictures over the years and I thought, ‘I don’t stand a chance.’ ” By the second day he had decided to “relax and enjoy it”. A week later he was told that Jack Warner, the head of Warner Brothers, had reviewed the screen tests, pointed at Walker and said: “That is Cheyenne.”

Initially paid $175 an episode (about £1,200 today), he joked that he had only got the role because he was cheap. Yet it was easy enough to see why Warner was prepared to take a gamble on the unknown actor. With his blue eyes, chiselled features and muscular physique, every inch of Walker’s rugged 6ft 6in frame resembled the perfect romantic image of a cowboy: from chest to waist to hip he measured 48-32-36. Such appeal meant that his shirt came off in an astonishing number of episodes. According to The New York Times, he was “the biggest, finest-looking western hero ever to sag a horse, with a pair of shoulders rivalling King Kong’s”.

His non-acting CV lent him an impressive authenticity too. He had worked on Mississippi riverboats, in the Texas oil fields and as a carnival roustabout before ending up as a deputy sheriff in Las Vegas. There he lived in a trailer and encountered the showbusiness types who frequented the casinos, including the actor Van Johnson, who had just starred in Brigadoon with Gene Kelly and suggested he try his hand in Hollywood.

Walker eagerly embraced the idea and headed for Los Angeles. “I’m not going to get that far carrying a gun and a badge, and it doesn’t pay that well,” he reasoned. “If you make movies, you make good money — plus the bullets aren’t real!”

The only attribute he lacked as a convincing cowboy was that he had never been on horseback. His height meant that he was impressively tall in the saddle, but when filming of the first series began, he confessed to considerable nervousness when he was required to mount his steed. “You’ll either be a good rider or a dead one,” he was told. There were times when he “wondered which one it was going to be”.

In Long Beach, California, he worked as an agent for a detective agency and in Las Vegas he combined his duties as deputy sheriff with working for security at the Sands Hotel and Casino.

By the time he arrived in Hollywood he was married to Verna Garver, a waitress, with whom he had a daughter. They divorced in 1968 and he married the actress and dancer Giselle Hennessy. After her death in 1994 he married Susan Cavallari, who survives him. They made their home in Grass Valley, California, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. He is also survived by Valerie Walker, his daughter from his first marriage, who is a retired pilot and was one of the first women to fly for a leading airline.

At the height of Cheyenne’s success Walker went on strike for nine months in a contract dispute with Warner Brothers and was replaced by a Bodie clone called Bronco Layne, who was played by Ty Hardin (obituary, August 14, 2017). When Walker returned on improved terms, Hardin was given his own spin-off series.

After Cheyenne finished, his most notable film appearances included None but the Brave, Frank Sinatra’s only movie as a director, and The Dirty Dozen, in which he had a memorable fight scene with Lee Marvin.

He survived a skiing accident in 1971 in the Sierra Nevada when his heart was punctured by a ski pole. “They rushed me to a hospital, where two doctors pronounced me dead,” he said. Fortunately a third doctor thought he could detect the faintest pulse and Walker was given open-heart surgery. Two months later he was back at work on the set of the movie Pancho Villa.

One of his final appearances before retirement came in 1995, when he reprised the character of Cheyenne Bodie in an episode of the TV series Kung Fu: The Legend Continues.

“I feel action is what I owe the public,” he once said. “When I see a hero yak-yak-yakkin’ I lose all interest.”