Hollywood Actors

Collection of Classic Hollywood Actors

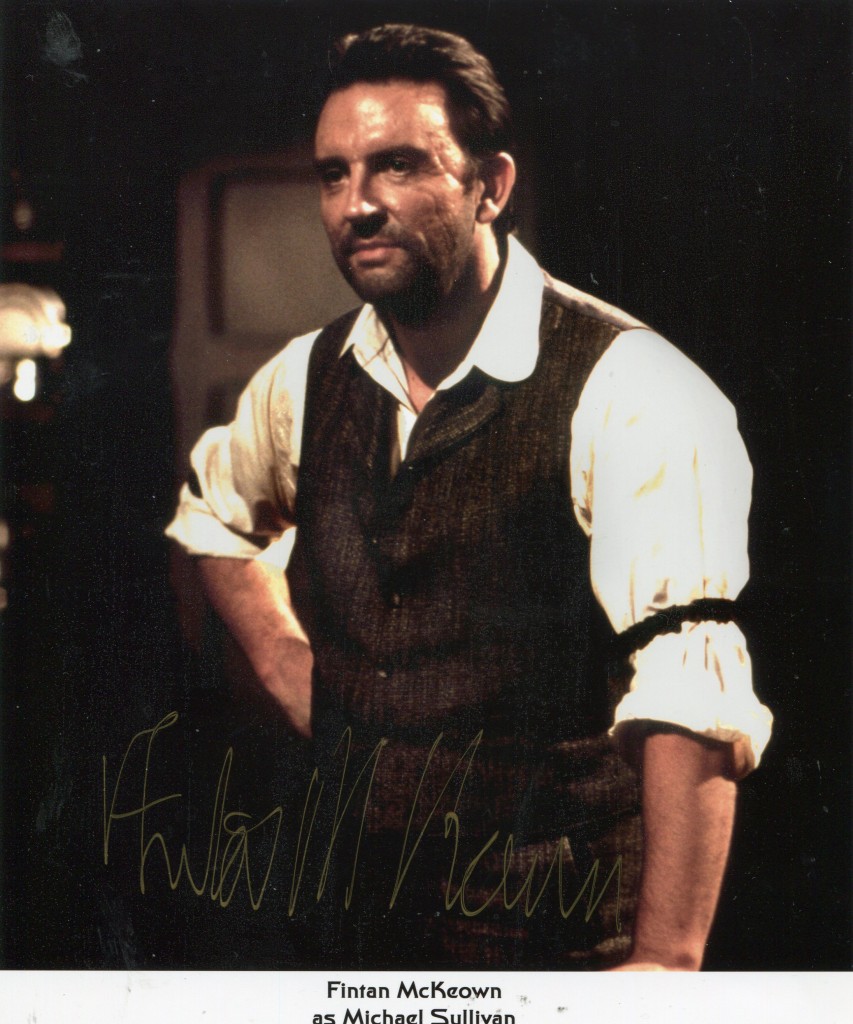

Fintan McKeown

Fintan McKeown is an actor, known for Waking Ned Devine (1998), Immortal Beloved(1994) and Mermaid Chronicles Part 1: She Creature (2001).

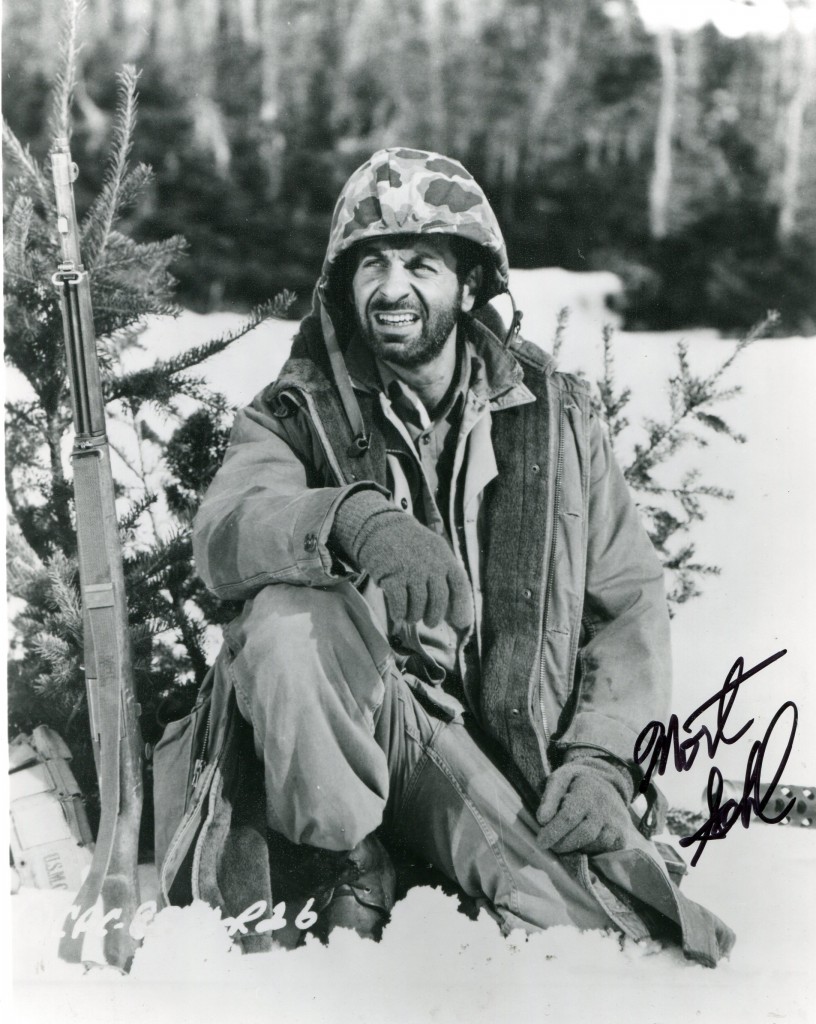

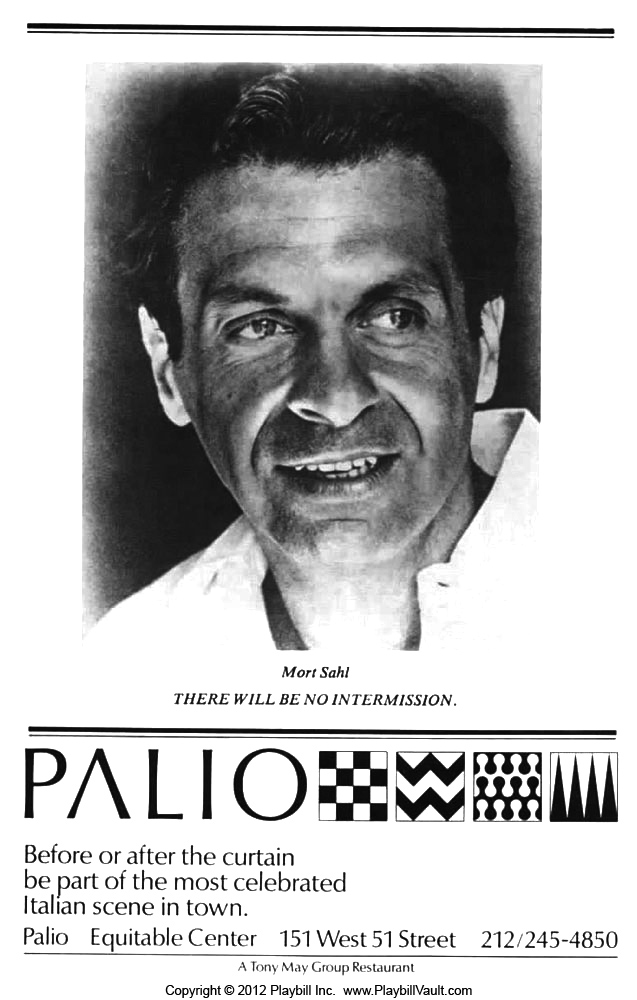

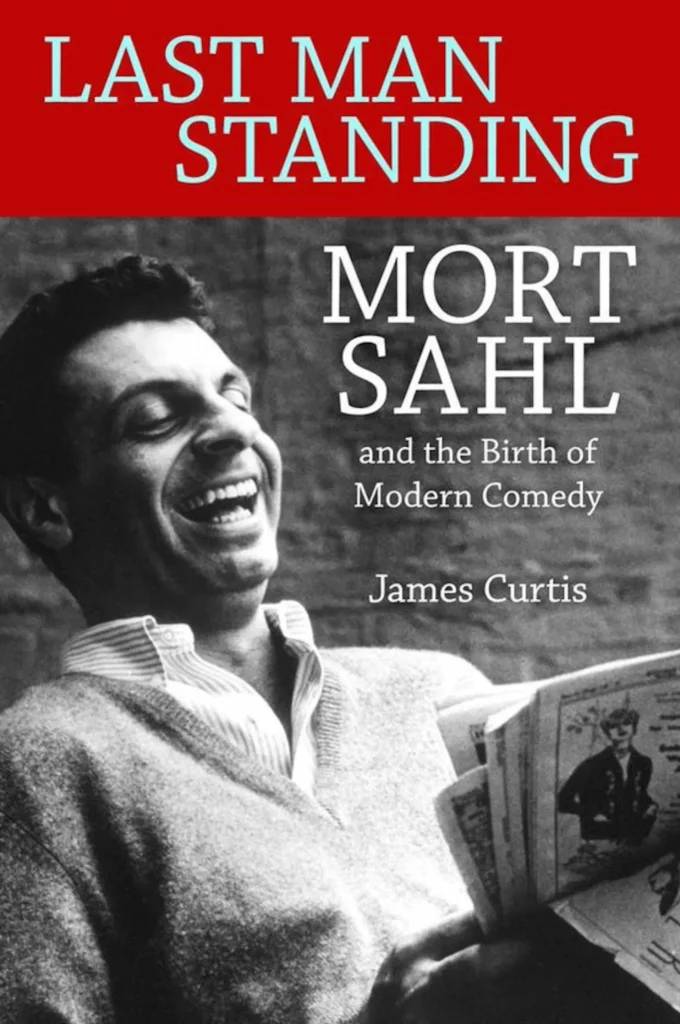

Mort Sahl

Wikipedia entry:

Sahl is a Canadian-born American comedian and social satirist, considered to be the first modern stand-up comedian since Will Rogers, a humorist in the early 20th century. Sahl pioneered a style of social satire which pokes fun at political and current event topics using improvised monologues and only a newspaper as a prop.

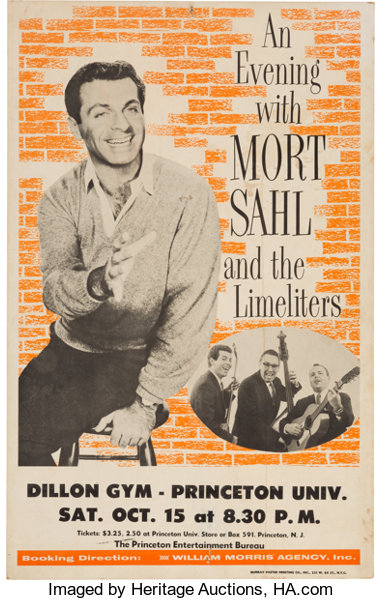

Sahl spent his early years in Los Angeles and moved to the San Francisco Bay Area where he made his professional stage debut at the hungry i nightclub in 1953. His popularity grew quickly, and after a year at the club he traveled the country doing shows at established nightclubs, theaters and college campuses. In 1960 he became the first comedian to have a cover story written about them by Time magazine. He appeared on various television shows, played a number of film roles, and performed a one-man show on Broadway.

Television host Steve Allen claimed that Sahl was “the only real political philosopher we have in modern comedy.” His social satire performances broke new ground in live entertainment, as a stand-up comic talking about the real world of politics at that time was considered “revolutionary.” It inspired many later comics to become stage comedians, including Lenny Bruce, Jonathan Winters and Woody Allen. Allen credits Sahl’s new style of humor with “opening up vistas for people like me.”

Numerous politicians became his fans, with John F. Kennedy asking him to write his jokes for campaign speeches. After Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, however, Sahl became obsessed with what he saw as the Warren Report‘s inaccuracy and conclusions, and spoke about it often during his shows. This alienated much of his audience and led to a decline in his popularity for the remainder of the 1960s. By the 1970s, however, his shows and popularity staged a comeback which continues to the present.

The above “Wikipedia” entry can also be accessed online here.

Mort Sahl died in 2021 aged 94.

Mort Sahl obituary

Comedian and satirist who revolutionised US standup in the 1950s, skewering politicians of every hue

Sean Garrison

Sean Garrison. Wikipedia.

The New York City native was signed up by Warner Bros. and launched his acting career in the 1957 episode “A Time to Die” of the ABC/Warner Brothers western television series, Colt .45, starring Wayde Preston. He appeared again on Colt .45 in 1958 as Charles “Chuck” Dudley in the episode “Circle of Fear”. In 1958, he had an uncredited role in the film Darby’s Rangers with James Garner. That same year he was cast as Mike Fullerton in the episode “The Empty Gun” of the ABC/WB western series Cheyenne, starring Clint Walker in the title role and appeared in Violent Road.

Garrison played Andy Gibson in the 1958 episode “The Canary Kid” of Sugarfoot, another ABC/WB western series with Will Hutchins in the title role. He also had a comedy role with Ricky Nelson in 1958 as George in “Stealing Rick’s Girl” on ABC’s The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet.

In 1958, Garrison played the role of Yeoman Kaffhamp in Onionhead, a military film with Andy Griffith. In 1959, he was cast as Seaman Floyd in the film Up Periscope. He had two film roles in 1961, as Glenn in Splendor in the Grass and as Fred Tyson in Bridge to the Sun.

In 1965, he was cast as Lloyd Garner in “The Young Marauders”, the fourth episode of the ABC western series The Big Valley.

In 1966, he played the role of Mark Dominic, the lover of Jean Seberg‘s character, in the mystery film Moment to Moment. Another 1966 role was that of the Reverend John Porter in the episode “Sanctuary” of Gunsmoke, a story of outlaws taking refuge in a church. He was cast in 1966 as Doug Pomeroy in “Runaway Boy” on Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre. In 1967, he played the role of Richard Tyson in the film Banning. He was considered for the role of Sir Lancelot in Camelot (1967)

In Dundee and the Culhane, Garrison joined John Mills as the junior partner of frontier lawyers taking clients in the American West. Garrison had relatively few acting roles thereafter, none long-lasting. In 1968, he was cast as Buck Hambleton in the episode “Ordeal” of The Name of the Game. In 1969, he played Samuel J. Coles in “A Reign of Guns” in The Mod Squad. In 1970, he was cast as George in “The Pied Piper of Rome” on the comedy To Rome with Love. In another 1970 appearance, he was cast in Love American Style. In 1971, he portrayed Harvey Bishop in “The 5th Victim”, the twelfth episode of Alias Smith and Jones. His subsequent roles included Clint Carpenter in “Harvest of Death” (1972) on Mannix, Detective Robert Scott in “The Violent Homecoming” (1973) of Police Story, Lanark in “The Second Chance” (1977) of The Rockford Files, Major Walter Layton in “The Hawk Flies on Sunday” (1977) of Baa Baa Black Sheep, and Captain Buck Tanner in “PlayGirl/Smith’s Valhalla (1980) of Fantasy Island.

Garrison’s last two acting roles were as Carl Belford in “The 18-Wheel Rip-Off” (1980) of B.J. and the Bear and as a physician in the episode “The Hawk and the Hunter” (1981) of CHiPs. Garrison died in March 2018 at the age of 80.

ClaramaeTurner

“New York Times” obituary from 2013.

Renowned for her lustrous voice, Claramae Turner sang more than 100 times with the Metropolitan Opera. But she is best known — or, more precisely, best unknown — for having introduced “I Left My Heart in San Francisco,” the sentimental ballad indelibly associated with Tony Bennett.

That song, with music by George Cory and lyrics by Douglass Cross, was written for Ms. Turner, an operatic contralto, in the early 1950s and published in 1954. She sang it often as a recital encore.

Then along came Mr. Bennett, who had a hit with it in 1962, won two Grammy Awards for it (record of the year and best male solo vocal performance) and has lived with it happily ever after.

Mr. Bennett’s recordings of the song have sold millions of copies. It has also been recorded by Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Judy Garland, Peggy Lee, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Tennessee Ernie Ford and a torrent of others.

Ms. Turner, who died on May 18, at 92, in Santa Rosa, Calif., was also known to audiences as Cousin Nettie in the 1956 film version of “Carousel,” the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical.

In that picture, which starred Shirley Jones and Gordon MacRae, Ms. Turner sings the enduring standards “You’ll Never Walk Alone” and “June Is Bustin’ Out All Over.”

At the Met, where Ms. Turner appeared regularly from 1946 to 1950, her roles included Amneris in Verdi’s “Aida,” Marcellina in Mozart’s “Marriage of Figaro,” Erda in Wagner’s “Siegfried” and Auntie in Britten’s “Peter Grimes.”

Reviewing her Met debut, as Marthe in Gounod’s “Faust,” in The New York Times, Noel Straus wrote, “Miss Turner accomplished some of the most able vocalism of the evening.” He added, “Hers is a warm, rich voice, admirably trained.”

Claramae Haas was born on Oct. 28, 1920, in Dinuba, Calif., near Fresno. She got her start, fittingly, in San Francisco, as a chorister in the San Francisco Opera.

She progressed to leading roles with the company, including Azucena in Verdi’s “Trovatore” and Madame de Croissy in the United States stage premiere of Poulenc’s “Dialogues of the Carmelites” in 1957.

In New York, Ms. Turner sang the original Madame Flora, the title character of “The Medium,” by Menotti, which had its world premiere at Columbia University in 1946.

After leaving the Met in 1950, Ms. Turner performed regularly with the New York City Opera, where she sang Carmen, Madame Flora and many other roles. During this period Mr. Cory, a friend from her San Francisco days by then unhappily transplanted to New York, began work on “I Left My Heart” for her.

Ms. Turner’s first marriage, to Robert Turner, ended in divorce; her second husband, Frank Hoffmann, died before her. A resident of Santa Rosa, she leaves no known immediate survivors, according to F. Paul Driscoll, the editor in chief of Opera News magazine, who confirmed the death.

Ms. Turner’s discography includes Humperdinck’s “Hansel and Gretel”; “The Tender Land,” by Aaron Copland; and the Verdi Requiem.

It does not include “I Left My Heart in San Francisco,” which she simply never got around to recording.

The above “New York Times” obituary can also be accessed online here.

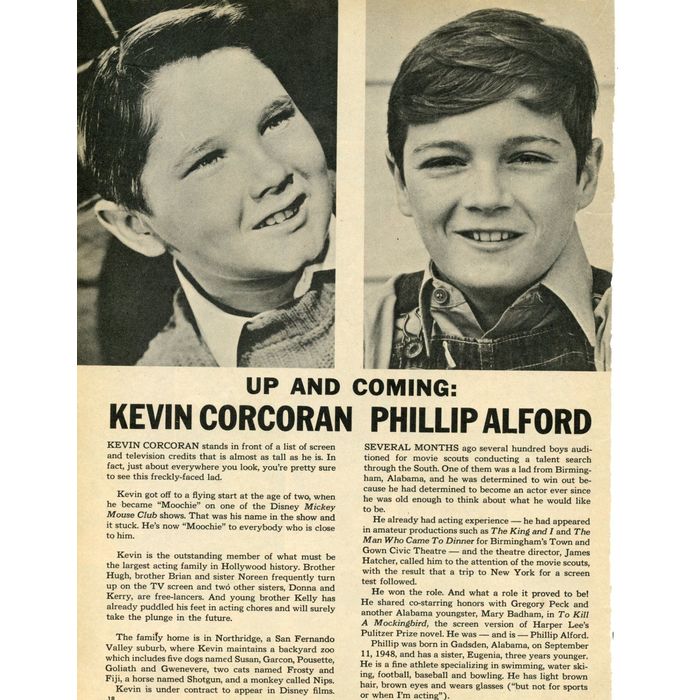

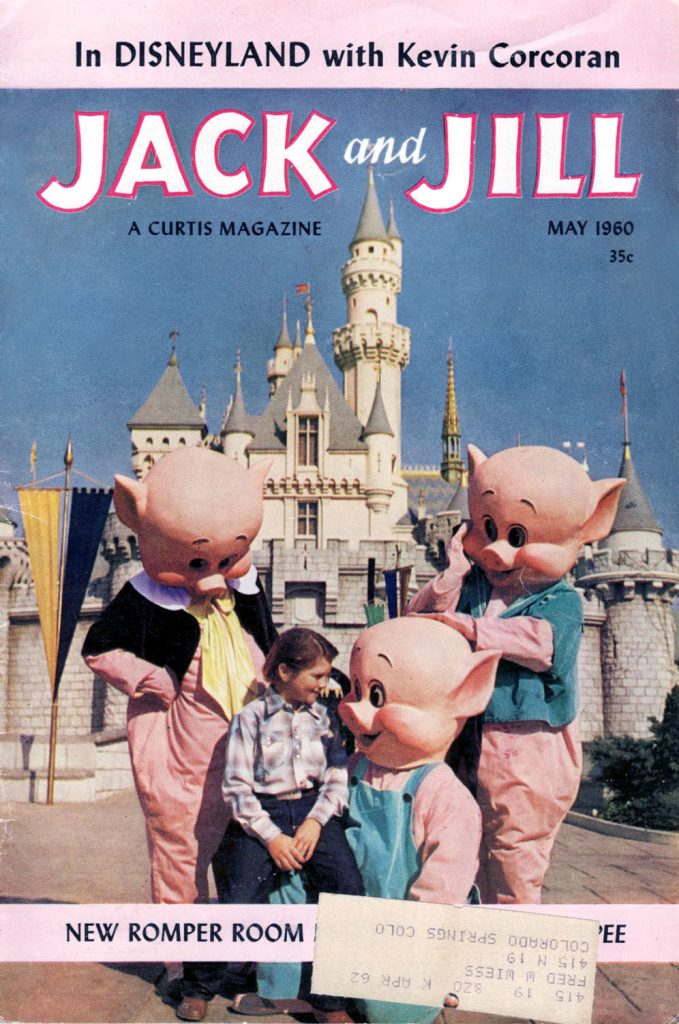

Kevin Corcoran

Kevin Corcoran was a very popular child actor in Disney movies of the late 1950s and very early 1960s. He died in 2015 at the age of 66.

“Guardian” obituary:

The name Walt Disney immediately conjures up Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse cartoons, as well as perennially popular animated features such as The Jungle Book and Bambi. But Disney was also once a purveyor of “live-action” family-friendly movies that spotlighted child actors, a favourite among whom was Kevin Corcoran, who has died of cancer aged 66.

Corcoran’s acting career with Disney began at the age of six when he appeared on television in a Mickey Mouse Club serial called Adventures in Dairyland (1956). In it he played a pugnacious little boy named Moochie, a nickname that stuck to him throughout his childhood and beyond. Walt Disney was so impressed with Corcoran’s debut that he had a special role written for Moochie in another Mickey Mouse Club serial, Further Adventures of Spin and Marty, which was aired the same year.

In 1957 Corcoran was given a leading role in Old Yeller, one of the best and most poignant boy-and-his-dog movies, still remembered as being a defining childhood experience for many baby boomers. Set in Texas in 1869, the film, discreetly directed by the Disney stalwart Robert Stevenson, tells of how Arliss (Corcoran) and his older brother Travis (Tommy Kirk) adopt a large yellow dog of indeterminate pedigree – “the best doggone dog in the west” as the title song declaims. At the tear-jerking climax, Travis is forced to shoot the faithful pooch, which has contracted rabies, much to the distress of Arliss.

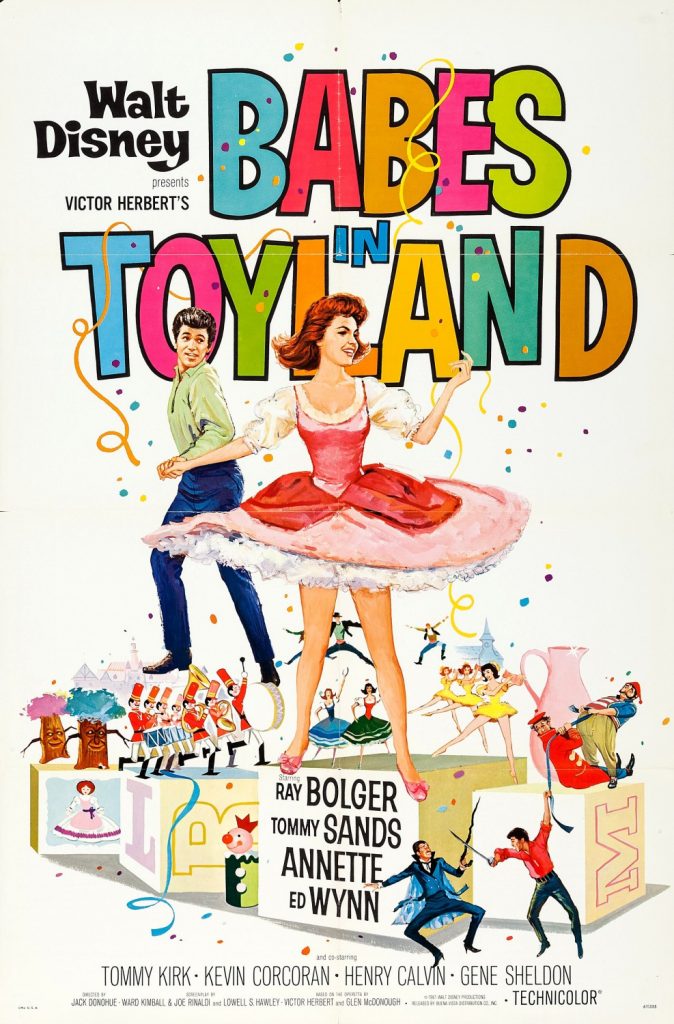

Corcoran went on to play Kirk’s slightly brattish kid brother again in four further movies, in which Kirk, eight years Corcoran’s senior, would portray a character going through a painful puberty, often irritated by his mischievous and talkative brother. “Don’t you ever run out of questions?” Kirk asks Corcoran in Old Yeller.

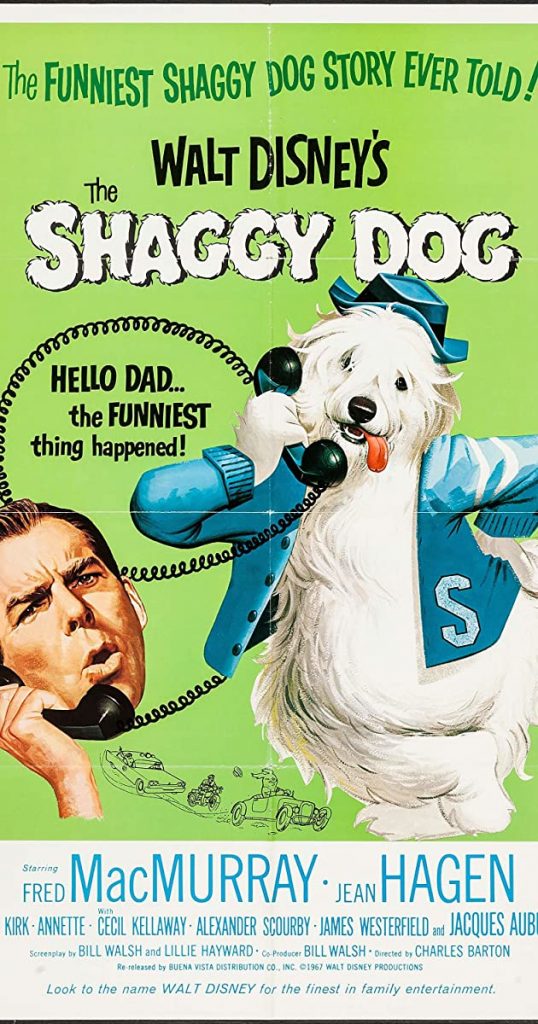

In the comedy-fantasy The Shaggy Dog (1959), Corcoran, though younger, is wiser than Kirk who, because of an ancient curse, is turned into a large sheep dog at inopportune moments. As the youngest member of the shipwrecked SwissFamily Robinson (1960), Corcoran collects all sorts of animals, getting in the way of Kirk, who is more interested in a girl he has helped rescue from pirates.

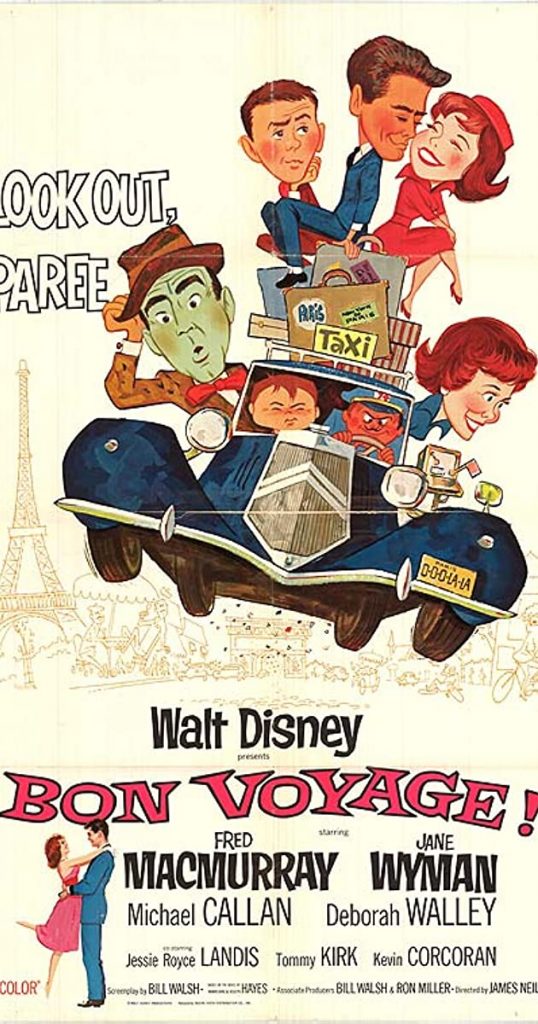

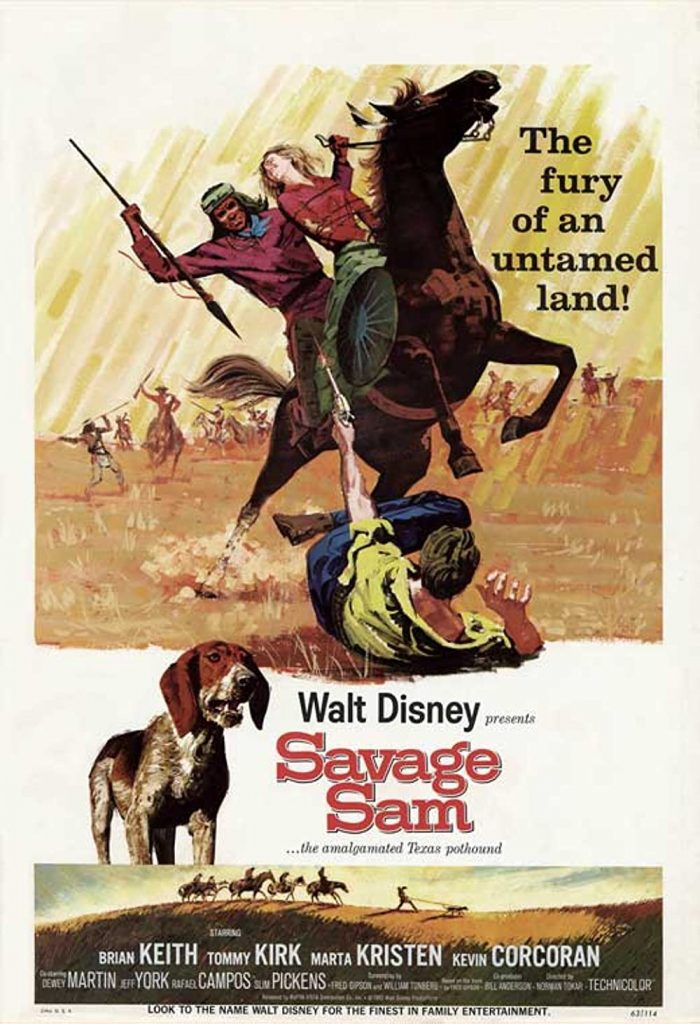

The screen brothers had a similar awkward relationship in Bon Voyage! (1962) as part of a “typical” American family on a tour of Europe. In Savage Sam (1963), a disappointing sequel to Old Yeller, Kirk and Corcoran reprised their roles, this time bickering over the defunct canine hero’s son. At one stage the boys’ uncle (Brian Keith) tells Kirk: “All little brothers hate bossin’. You’ve got to learn how to outfigger him.”

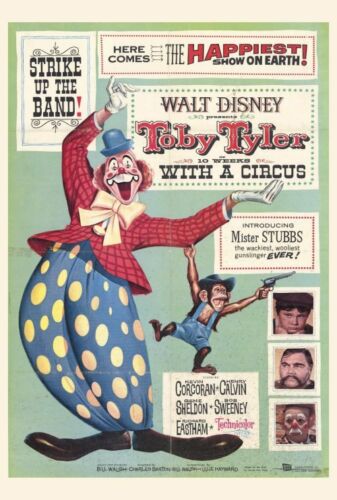

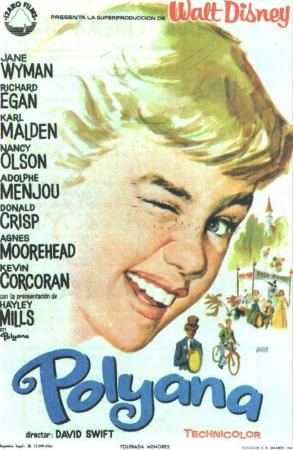

Other Disney movies in which Corcoran had leading roles were Pollyanna (1960), where, as Jimmy Bean, a mischievous orphan boy, he counterbalances the sweetness and light spread by the 12-year-old heroine (Hayley Mills), and Toby Tyler (1960), in which he played the title role, another orphan, this time running away from his foster parents to join a circus, where he makes friends with an endangered chimpanzee.

However, after A Tiger Walks (1964), another animal movie aimed at children – a tiger is threatened with death after escaping from a circus – Corcoran, at the grand old age of 15, quit acting. “I decided to retire when I realised that I knew more about movies than the guys making them,” he said.

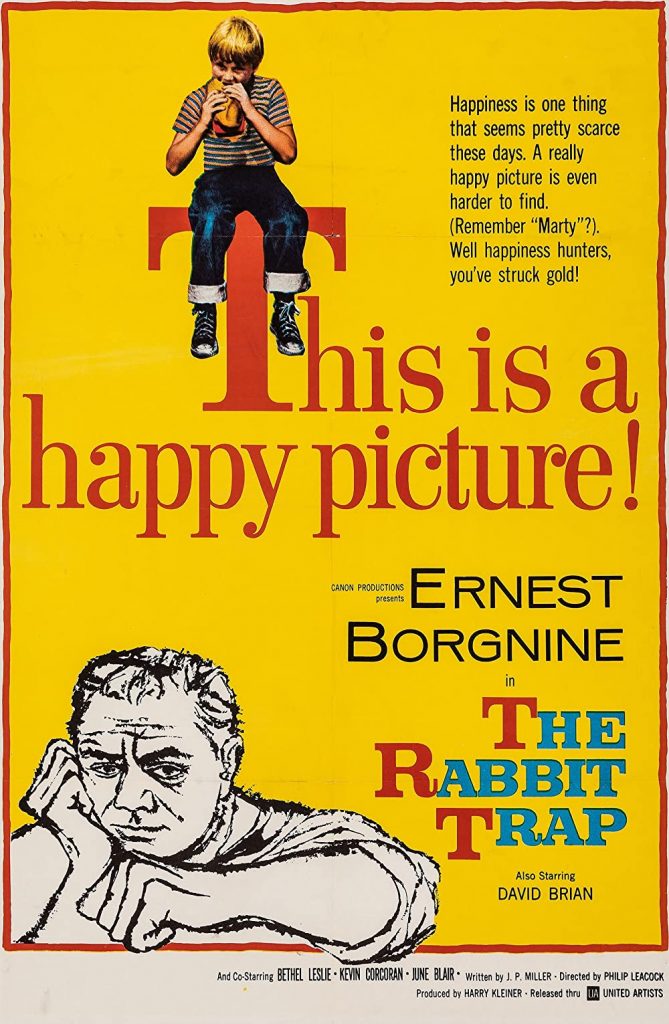

He had already been in the business for a long time, having, from the age of four, had brief roles in several feature films even before he signed with Disney. These included The Glenn Miller Story (1954) as the bandleader’s son; as the childhood incarnation of the lead character Paul van Riebeck (Tyrone Power) in Untamed (1955), and as one of Quaker farmer Ernest Borgnine’s children in Violent Saturday (1955). Corcoran’s real sisters, Noreen and Donna, played the other children.

Born in Santa Monica, California, to Kathleen and Bill, an MGM studio policeman, Corcoran had seven siblings, all of whom did some film acting. “While my father was working at MGM, he heard that children were needed to play some extra roles,” Corcoran recalled. “By the time I arrived – No 5 of eight children – the Corcoran kids had been established in the industry.”

Young Kevin was fortunate to come along during a successful period of Disney’s live-action movies. But Disney was fortunate too, because Corcoran embodied its vision of the “American everykid”, who the studio saw as “a highly intelligent human being – characteristically sensitive, humorous, open-minded, eager to learn, [with] a strong sense of excitement, energy, and healthy curiosity about the world in which he lives.”

After his early retirement from acting, Corcoran went to California State University, where he graduated with a degree in theatre arts. He then returned to Disney, later working as an assistant producer, but mainly as an assistant director, on a number of television series – including Baywatch and Murder, She Wrote. Over the years he was persuaded to play small parts in one US-based television series (My Three Sons, 1967) and two films (Blue in 1968 and It Starts with Murder in 2009).

He is survived by his wife, Laura (nee Soltwedel), whom he married in 1972, by three sisters, Che, Noreen and Kerry, and by a brother, Hugh.

• Kevin Corcoran, actor and director, born 10 June 1949; died 6 October 2015

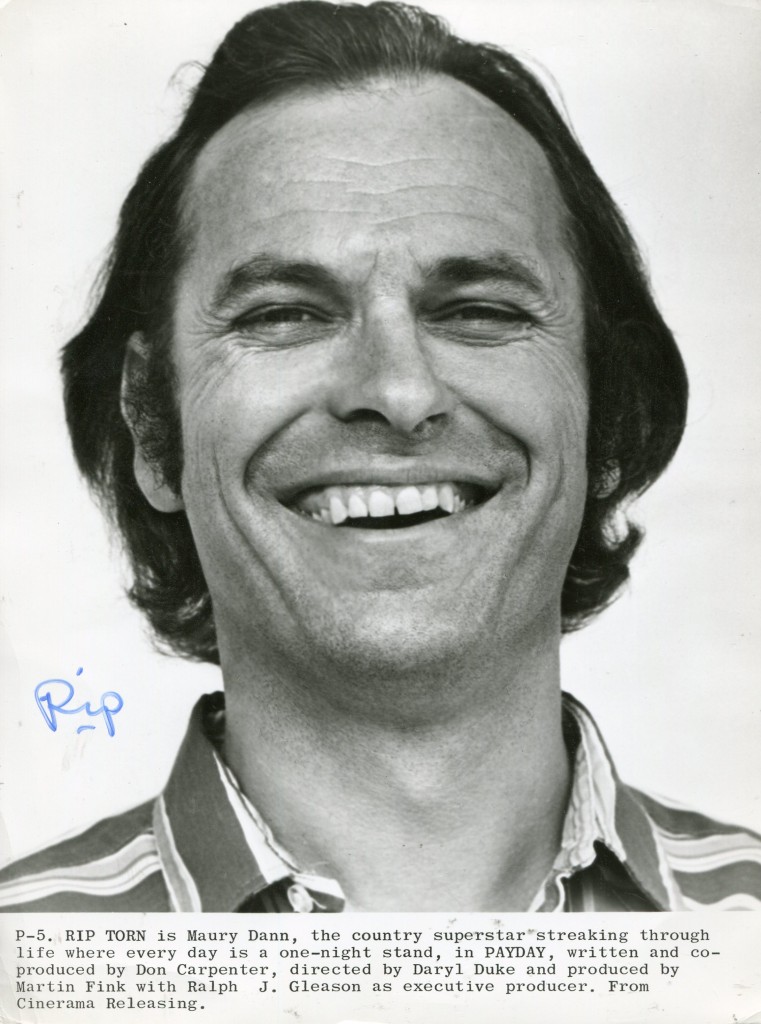

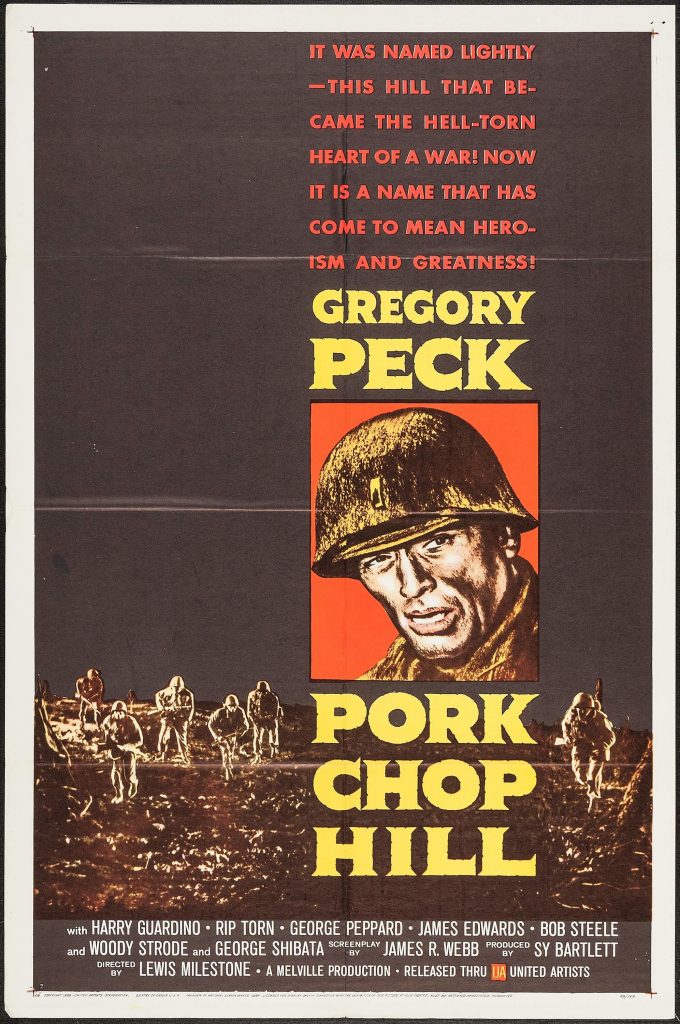

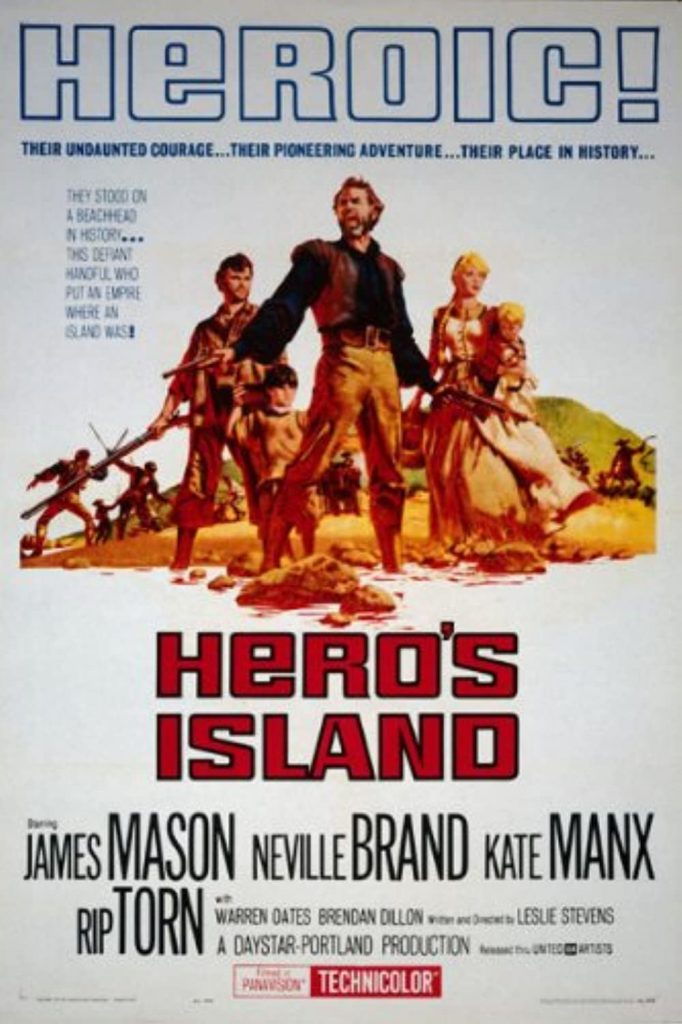

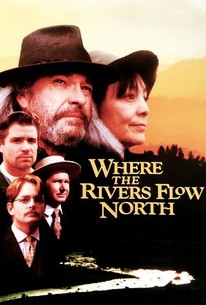

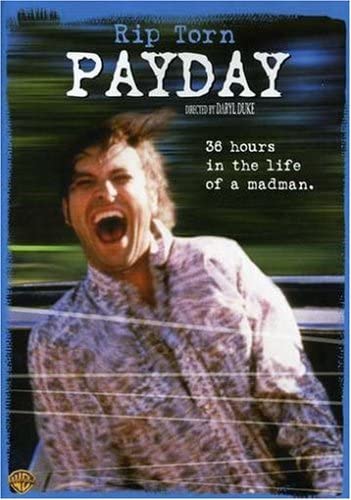

Rip Torn

Rip Torn obituary in “The Guardian” in 2019.

Although Rip Torn, who has died aged 88, had almost as silly a name as Slim Pickens, Stepin Fetchit and Parkyakarkus, he was a major actor whose powerful presence was felt in films, TV and on stage for more than 60 years.

He became most widely known as Artie, the foul-mouthed, dyspeptic talk show producer in The Larry Sanders Show (1992-98), for which he received six consecutive Emmy award nominations as best supporting actor in a comedy series, winning the award in 1996. Typical was his exchange with the studio janitor: “Nicolae, my man, you and I both clean up shit for a living. The only difference is my shit talks back.”

Torn had gained a reputation as a risk-taker and a hellraiser in the 1960s. His artistic collaboration with the macho novelist Norman Mailer on the partially improvised film Maidstone (1970) became notorious for the sequence in which Torn, looking stoned, unexpectedly attacks Mailer with a small hammer, drawing blood. This results in a vicious wrestling match in which Mailer bites Torn’s ear, while Mailer’s wife and children scream in horror. The fight is broken up with the two trading insults.

In 1969, Dennis Hopper offered Torn the role of the pot-smoking lawyer in Easy Rider. Torn withdrew from the project after he and Hopper got into a bitter argument in a New York restaurant ending with Hopper pulling a knife on Torn. As a result, Torn was replaced by Jack Nicholson, whose appearance in the film launched him into stardom.

In 1994, Hopper told Jay Leno on The Tonight Show that it was Torn who had pulled a knife on him. Torn sued. A judge heard from both sides, and from witnesses who had been at the restaurant, and decided to award Torn $475,000. When Hopper appealed, another judge doubled the award.

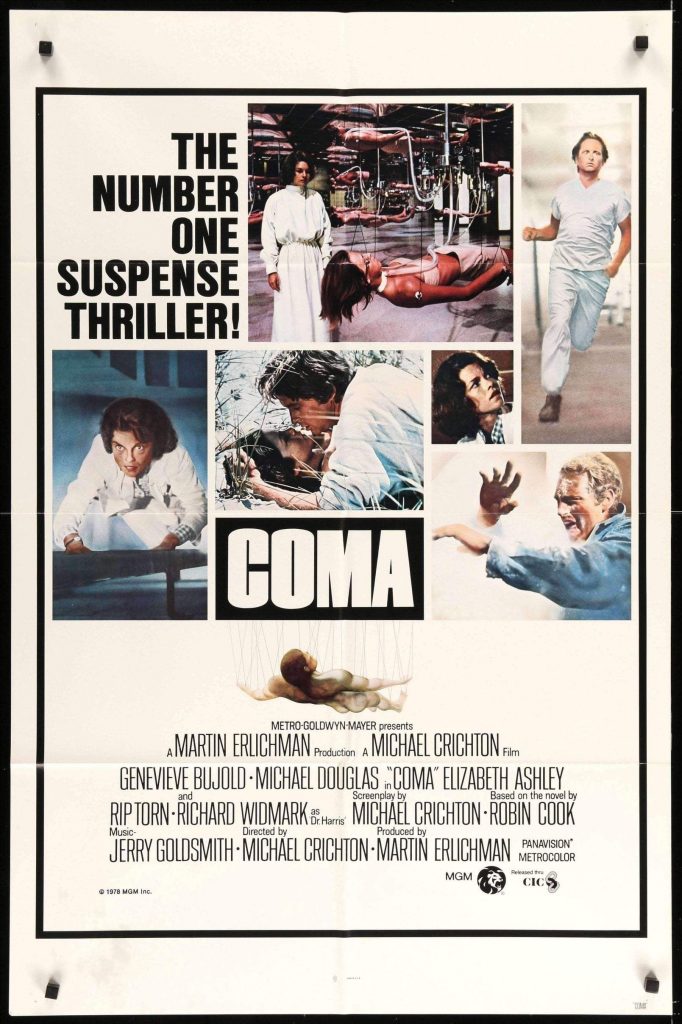

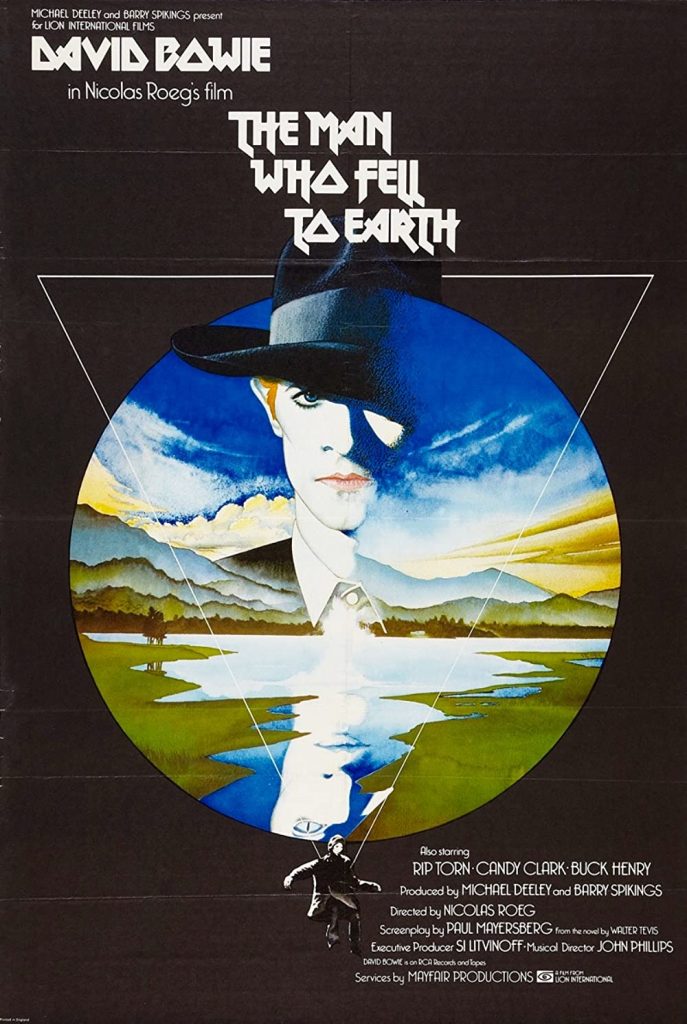

From the mid-70s, Torn alternated between mainstream and unconventional pictures, and between heroes and villains. Among his better roles were an untrustworthy, womanising chemistry professor trying to get David Bowieback to his home planet in Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976); the sinister head anaesthetist in Michael Crichton’s Coma (1978); the boozing and philandering southern senator in Jerry Schatzberg’s The Seduction of Joe Tynan (1979); and the humane farmer in Martin Ritt’s Cross Creek (1983), for which Torn gained a best supporting actor Oscar nomination.

Later well-known film roles include Agent Zed, head of the MIB organisation that supervises extraterrestrials hidden among the population of Earth in Men in Black (1997) and its two sequels, and the veteran coach Patches O’Houlihan in Dodgeball (2004).

He was born Elmore Rual Torn in Temple, Texas, the son of Thelma (nee Spacek) and Elmore Torn. Generations of Torns were called Rip, as was his father, an agriculturalist. Because his first ambition was to be a rancher, Torn studied animal husbandry at the University of Texas. Thinking that becoming a movie star was a good way to earn enough money to buy a ranch, he hitch-hiked to Hollywood in his early 20s. However, he failed to get near a studio and, after a few years of odd jobs, made his way to New York and the Actors Studio. There, he got to know Elia Kazan, who helped himlaunch his career.

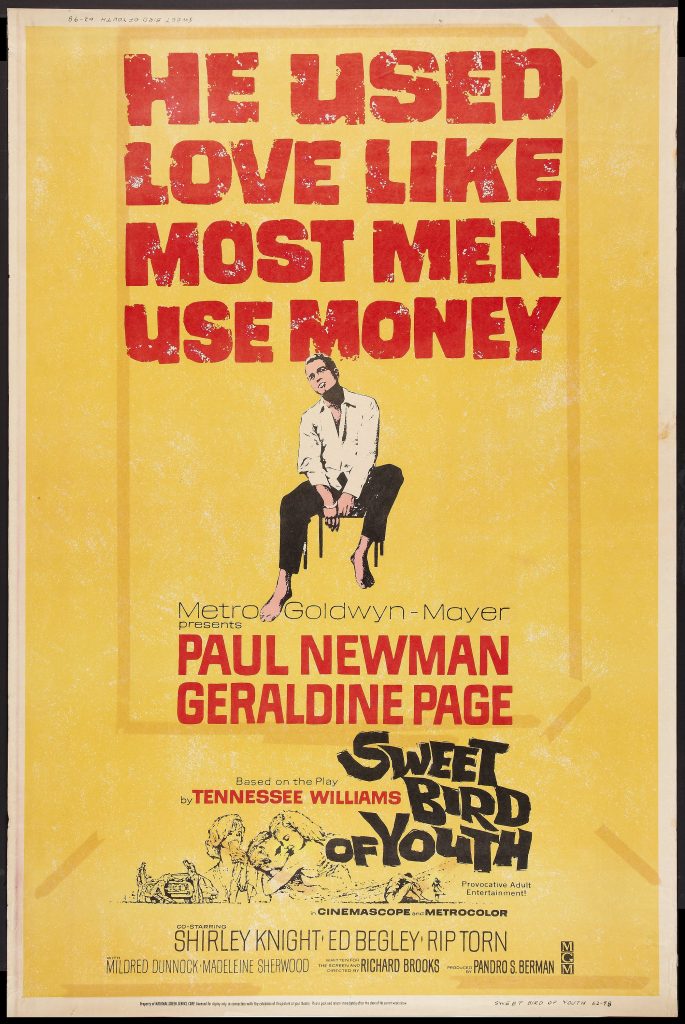

Kazan gave Torn two small parts: in Baby Doll (1956), as the young dentist with whom Carroll Baker flirts, and in A Face in the Crowd (1957), as the “greatest thing since Will Rogers” waiting to replace the folk hero Andy Griffith. Then Kazan cast him in his Broadway production of Tennessee Williams’s Sweet Bird of Youth (1959) as Tom Finley Jr, a nasty piece of work who attempts to drive the hero, Chance Wayne (Paul Newman), out of town, and finally castrates him.

When Newman left the show, Torn took over as Chance Wayne opposite Geraldine Page. For the 1962 film version, Torn reverted to Tom Finley Jr while Newman and Page repeated their stage roles. Torn and Page got married (both for the second time) in 1963 and remained so until her death in 1987. (Their country estate was called Torn Page.) They played domineering parents in Francis Ford Coppola’s second feature, You’re a Big Boy Now (1966), but seldom worked together despite pursuing parallel careers.

Torn developed his dynamic, loud-mouthed, somewhat sleazy, acting persona in a number of film roles in the 60s including Judas in Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings (1961), a sadistic army sergeant in Cornel Wilde’s Beach Red (1967), and the wealthy New Orleans businessman, waiting to get his revenge, in any fashion, on Edward G Robinson for wiping him out in a high-stakes poker game in Norman Jewison’s The Cincinnati Kid (1965).

In the last of these, when asked why he was surely not doing it for the money, Torn replies in his most villainous southern tones: “Yes, for my kind of money, gut money. I want to see that smug old bastard gutted. Gutted!”

Torn’s first collaboration with Mailer was in the off-Broadway production of The Deer Park (1967), adapted from Mailer’s controversial 1955 Hollywood novel. As the pimp Marion Faye, Torn won a distinguished performance Obie award. In Mailer’s “experimental” films, Torn played a hippy accused of murder in Beyond the Law (1967) and he was Raoul Rey O’Houlihan, half-brother of Norman Kingsley (Mailer), a film director turned politician, in Maidstone.

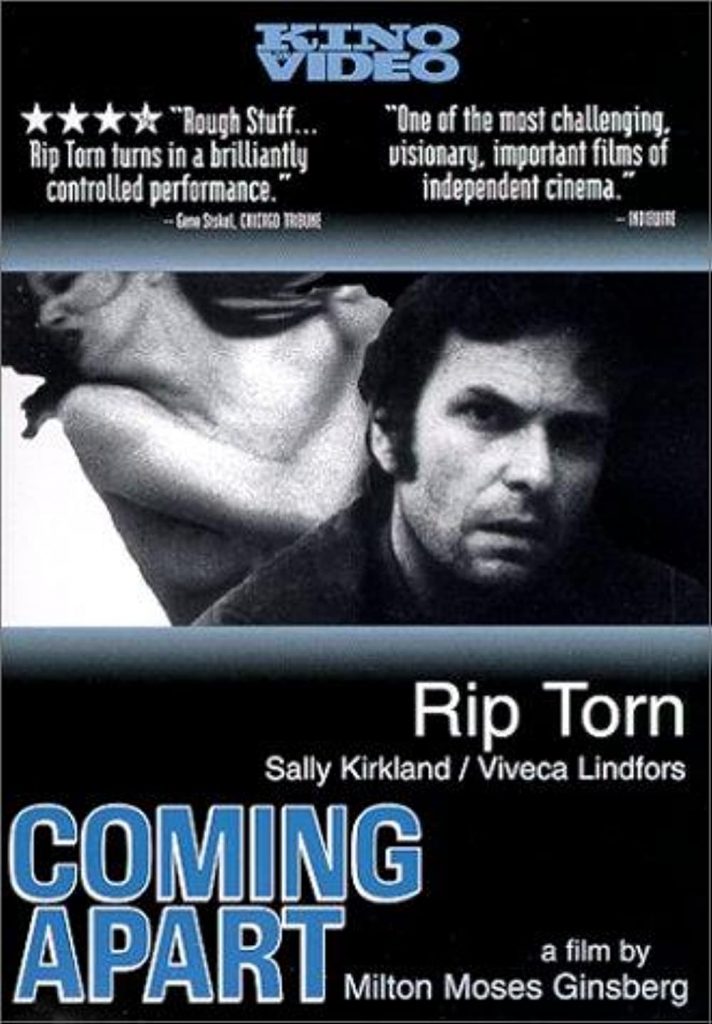

In Milton Moses Ginsberg’s Coming Apart (1969), Torn starred as a psychiatrist who films all his sessions with his female patients, then his own breakdown, with a hidden camera. This was followed by a rather shambling performance as Henry Miller in Joseph Strick’s Tropic of Cancer (1970), an updated version of the classic erotic novel, and Payday (1973), in which Torn, as a fading country-and-western singer, gave one of his best performances, revealing the vulnerability under a cruel and selfish exterior.

He won another Obie for his direction of Michael McClure’s The Beard (1968), about the meeting between Jean Harlow and Billy the Kid in eternity. A huge light show preceded the play, with cages of doves and ferrets in the lobby to “set off an adrenaline rush”.

Torn ventured into film directing for the first and last time with The Telephone (1988), a quasi one-woman comedy starring Whoopi Goldberg, who reportedly refused to stick to the script and had the director’s chosen director of photography, the veteran cinematographer John Alonzo, replaced by her then-husband, David Claessen. Torn cut his own version of the film, using the takes that adhered to the script, and screened it at the Sundance film festival, while the studio released its own version, to disastrous reviews.

On television, Torn was perfectly cast as Richard Nixon in the miniseries Blind Ambition (1979), and played Big Daddy in Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1984), and Boss Finley in a return to Sweet Bird of Youth (1989). After The Larry Sanders Show, he was successful in another long-running comedy series, 30 Rock, as Don Geiss, the head of the fictional TV network (2007-09).

Torn’s long struggle with alcohol frequently brought him on to the front pages. In 2004 he was arrested in New York City after his car collided with a taxi, and in 2006 and 2008 for drunk driving incidents. In 2010, he broke into a bank in Connecticut; he was charged with various offences including carrying a firearm while intoxicated and first-degree burglary, and was given a suspended sentence.

Torn is survived by his third wife, Amy Wright, and their two daughters, Katie and Claire; by a daughter, Danae, from his first marriage, to Ann Wedgeworth, which ended in divorce; by two sons, Anthony and Jonathan, and a daughter, Angelica, from his marriage to Page; and by four grandchildren.

• Rip Torn (Elmore Rual Torn Jr), actor, born 6 February 1931; died 9 July 2019

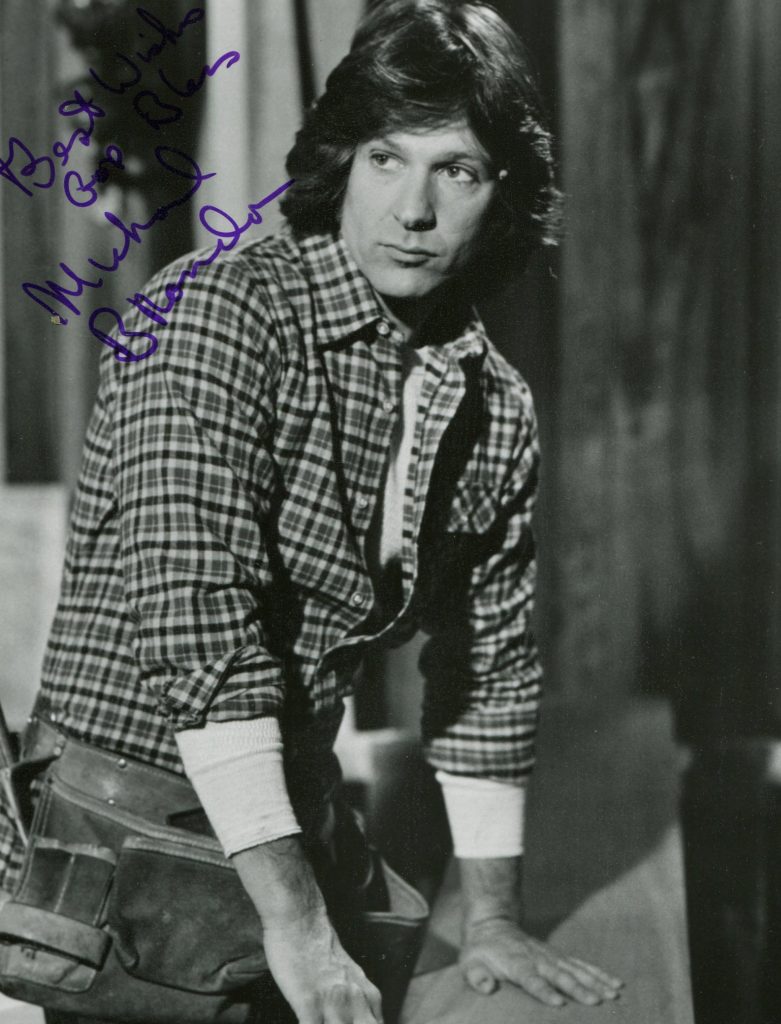

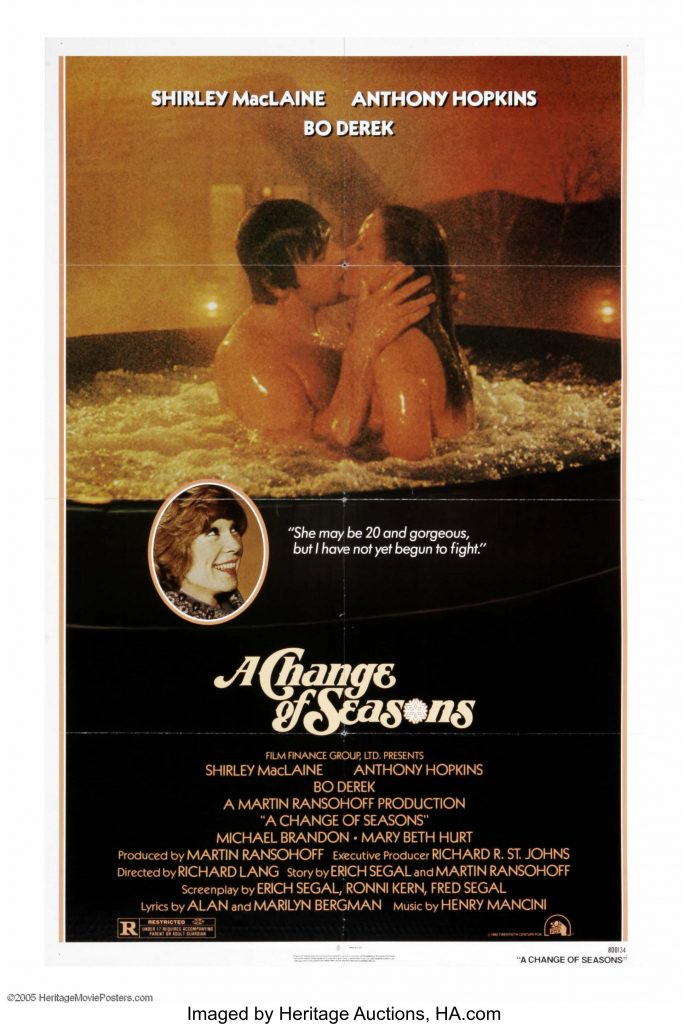

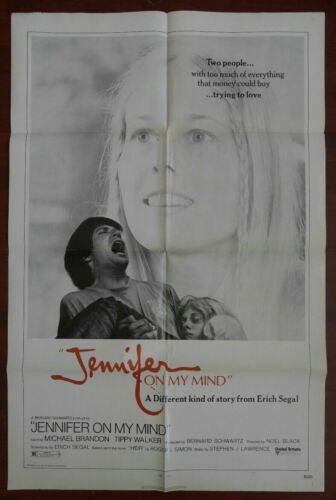

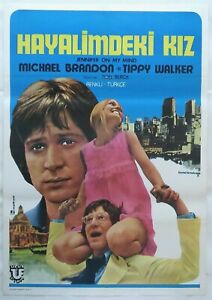

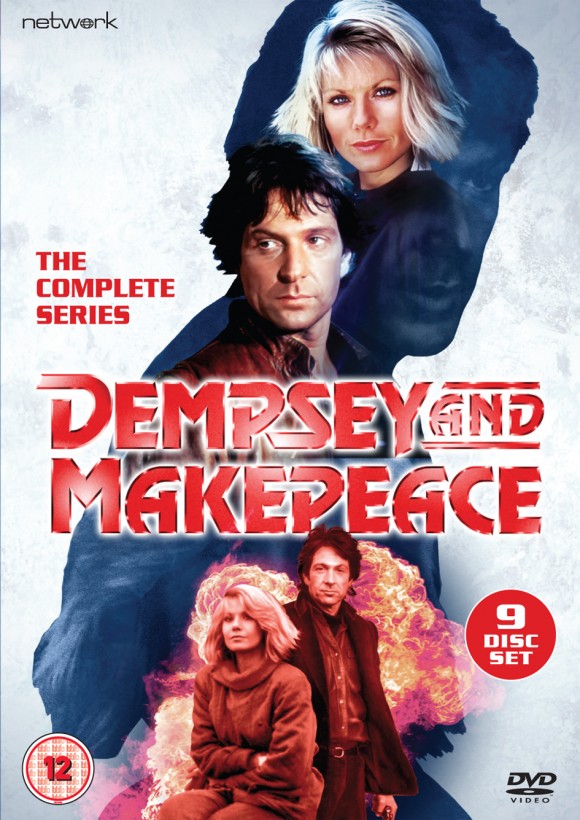

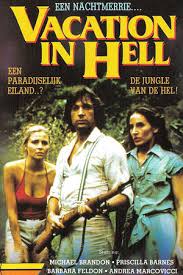

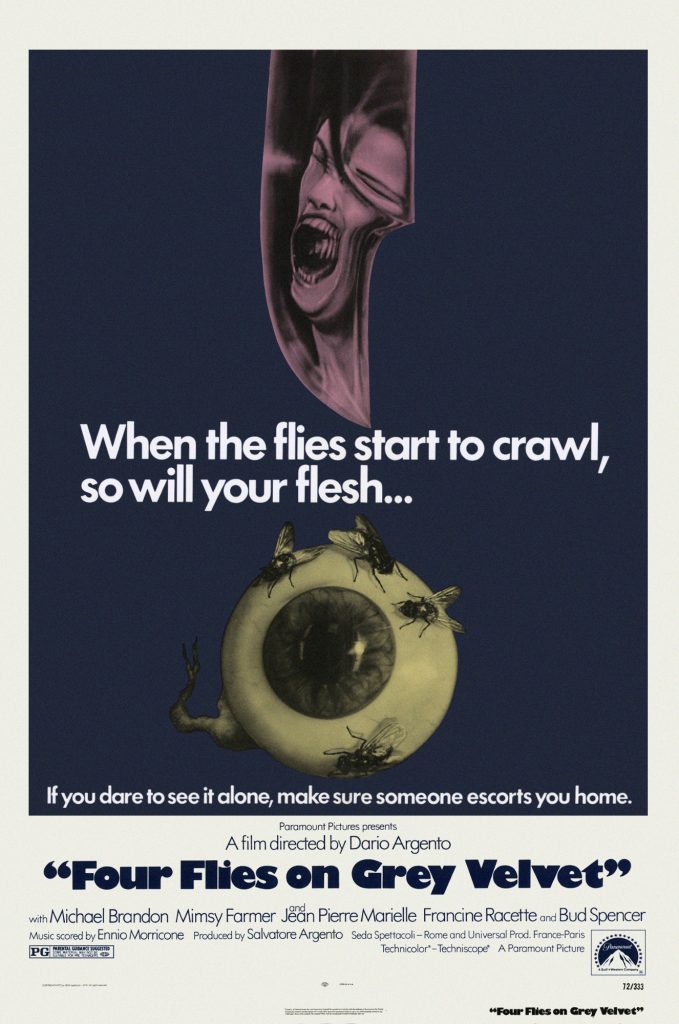

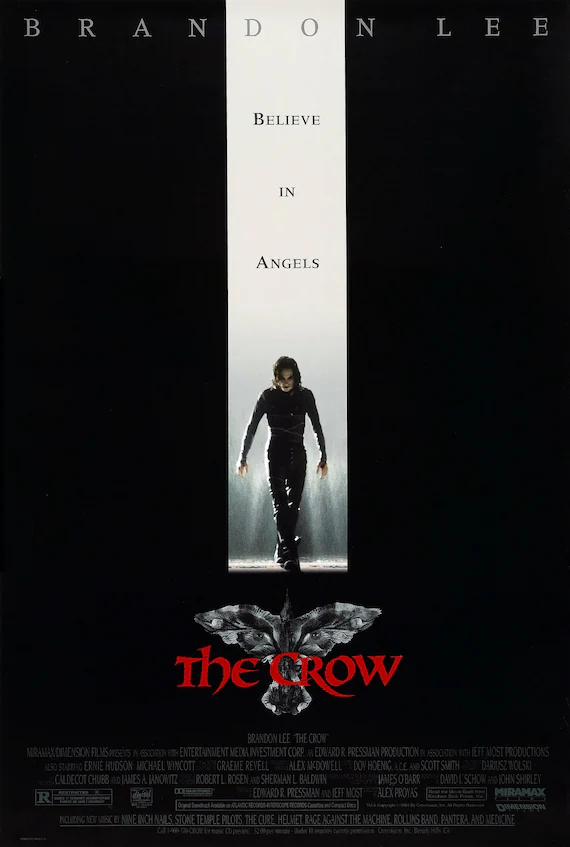

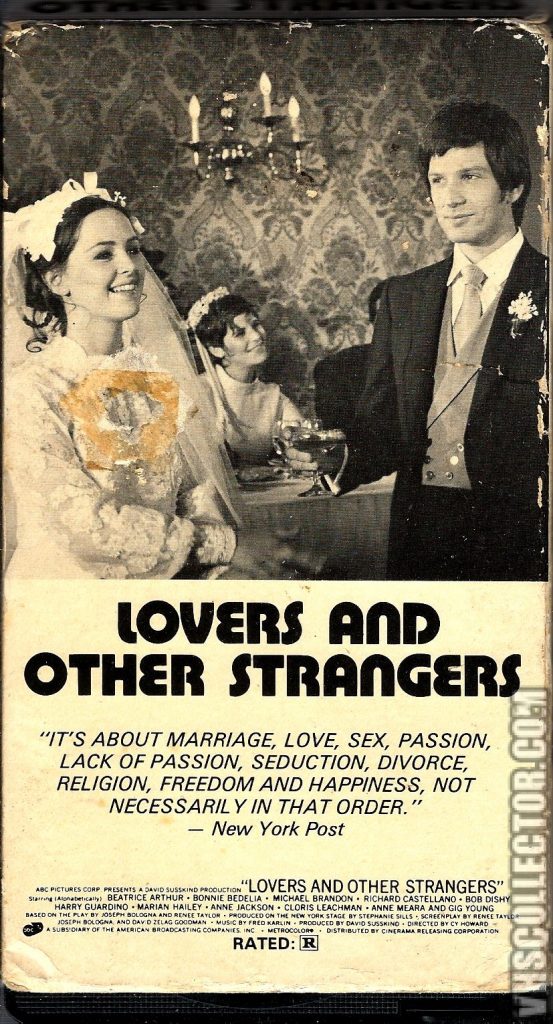

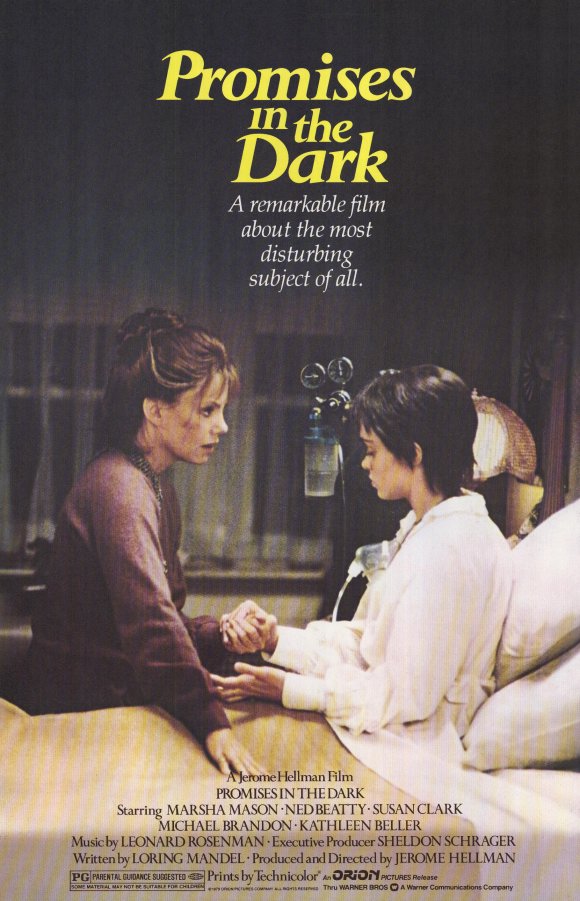

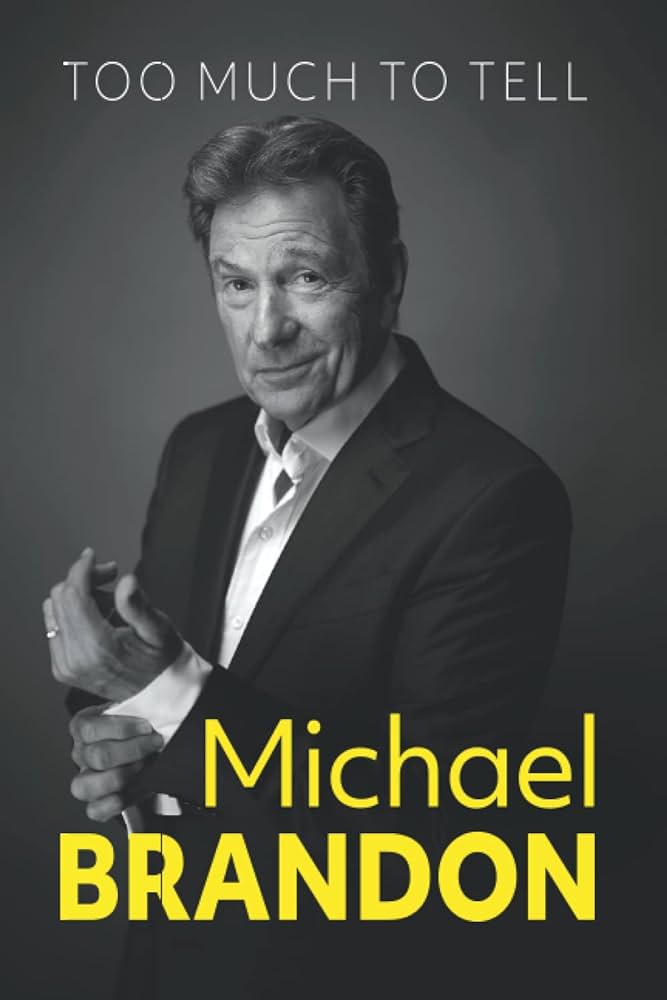

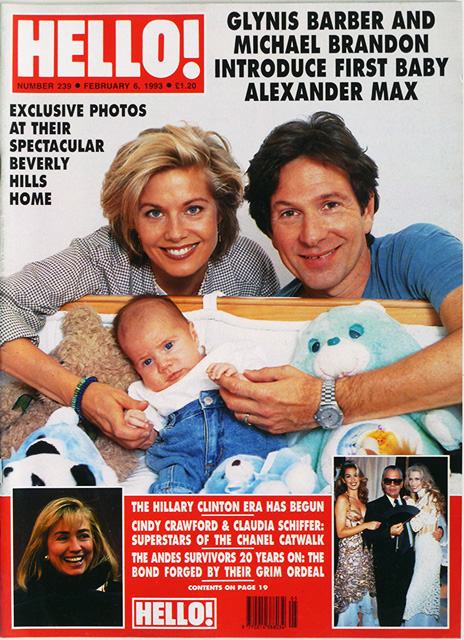

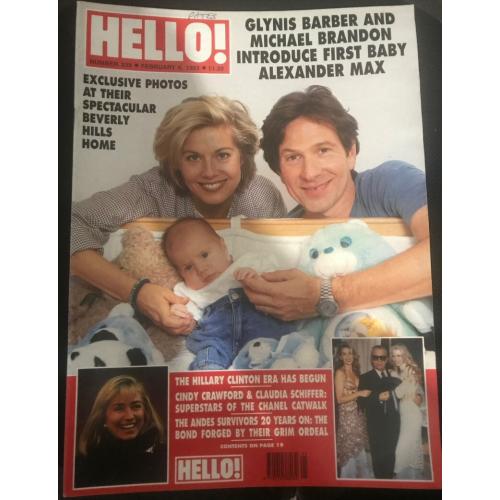

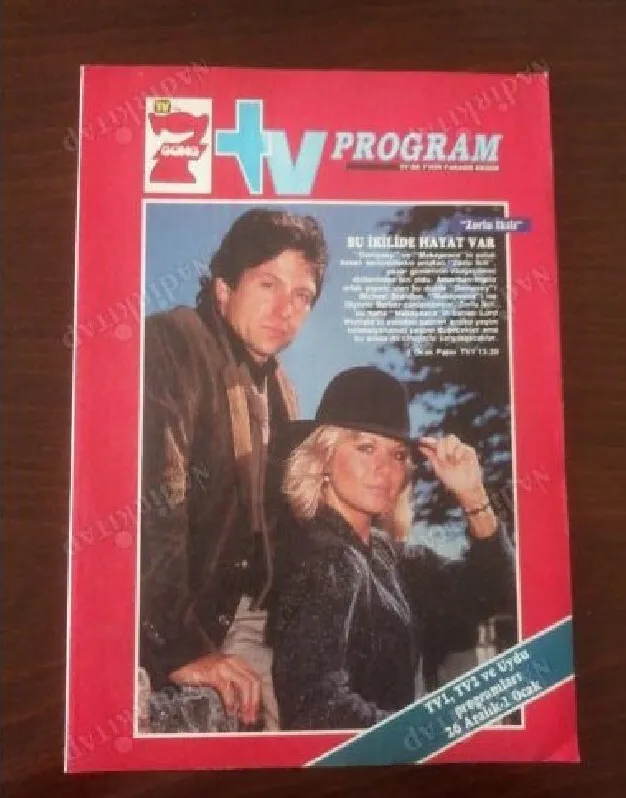

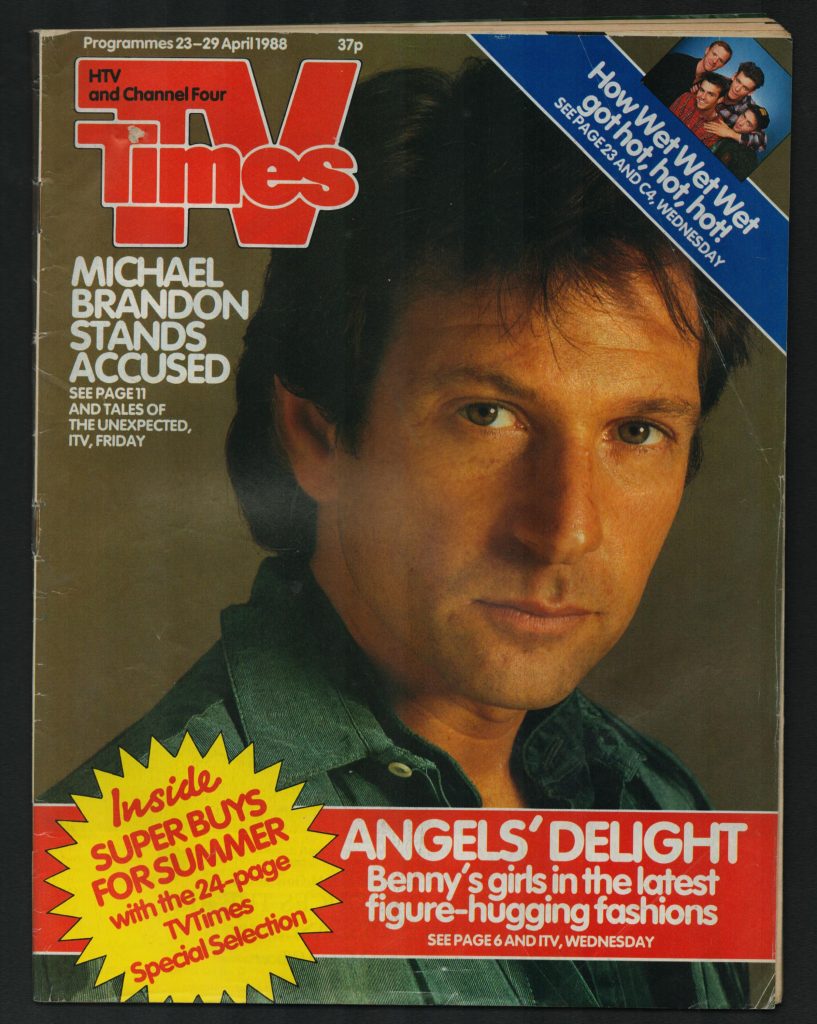

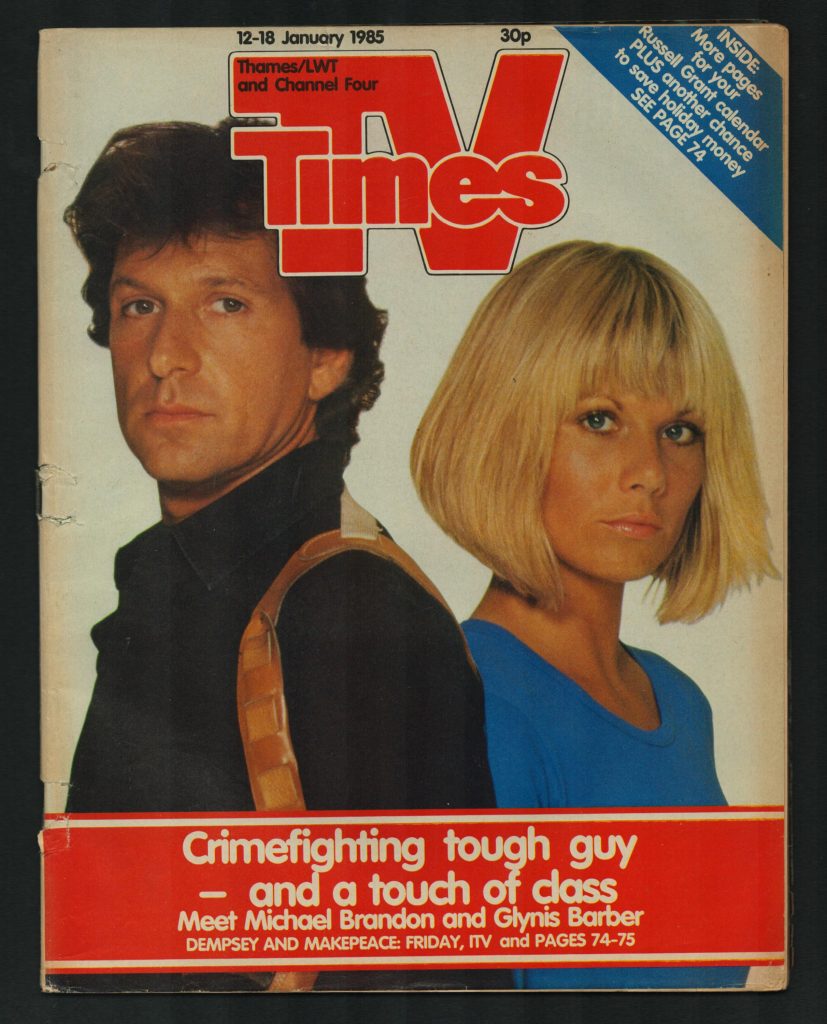

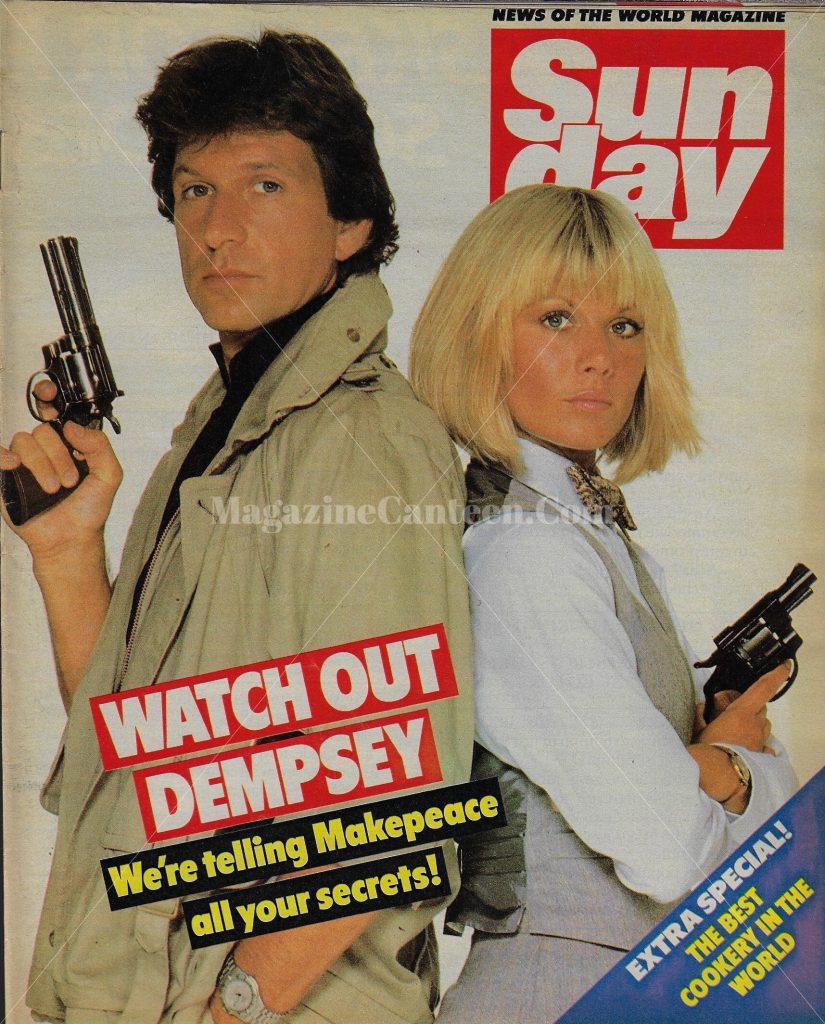

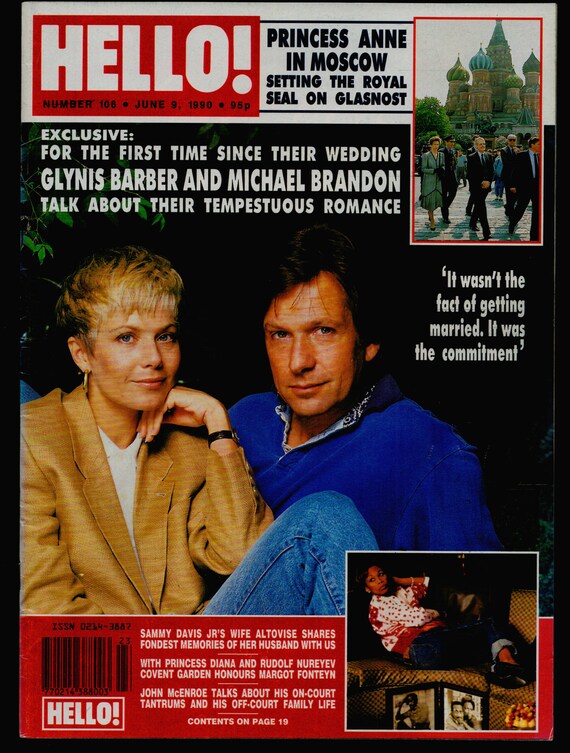

Michael Brandon

IMDB Overview:

Michael Brandon was born on April 20, 1945 in Brooklyn, New York, USA as Michael Feldman. He is an actor and director, known for Thomas & Friends (1984), Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) and Dempsey and Makepeace (1985). He has been married to Glynis Barber since November 18, 1989. They have one child. He was previously married to Lindsay Wagner.

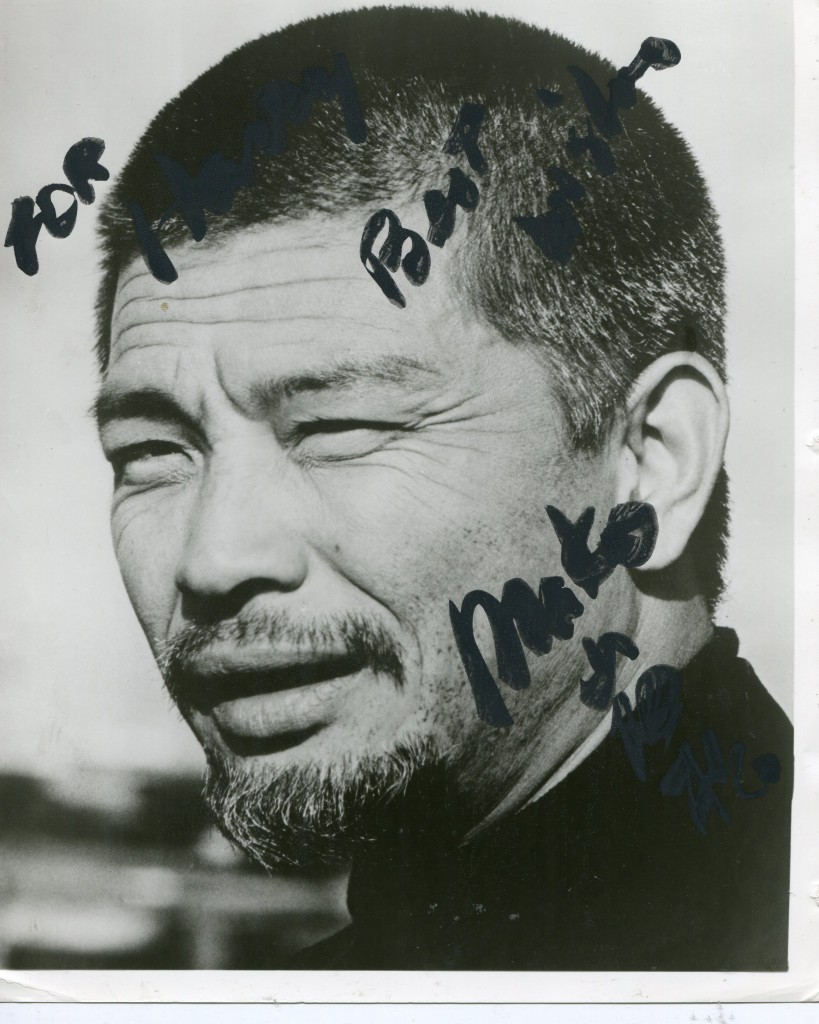

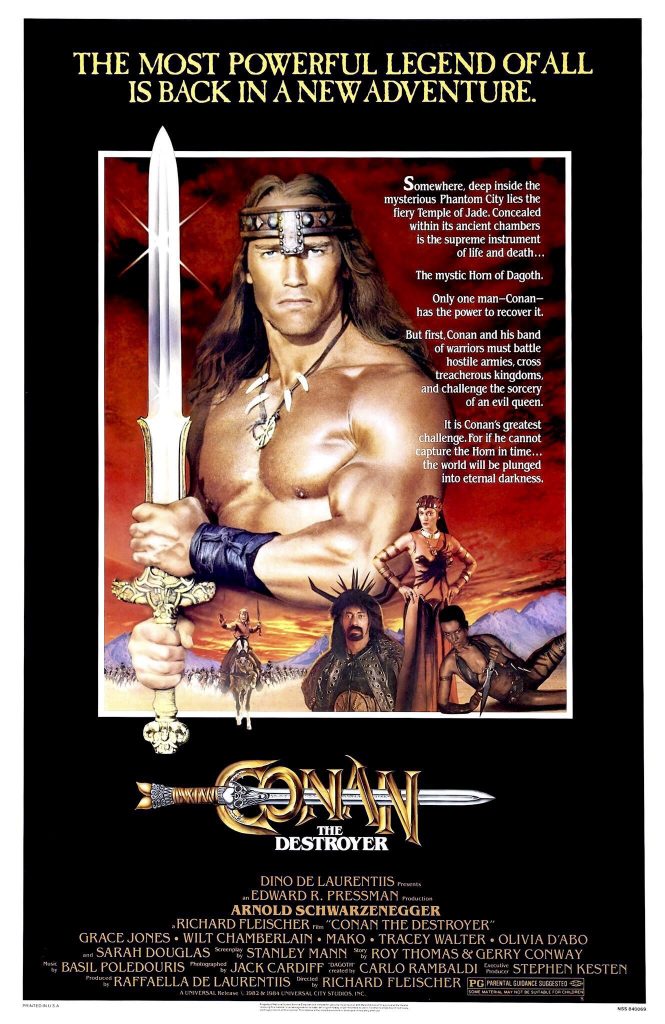

Mako

“Playbill” obituary from 2006:

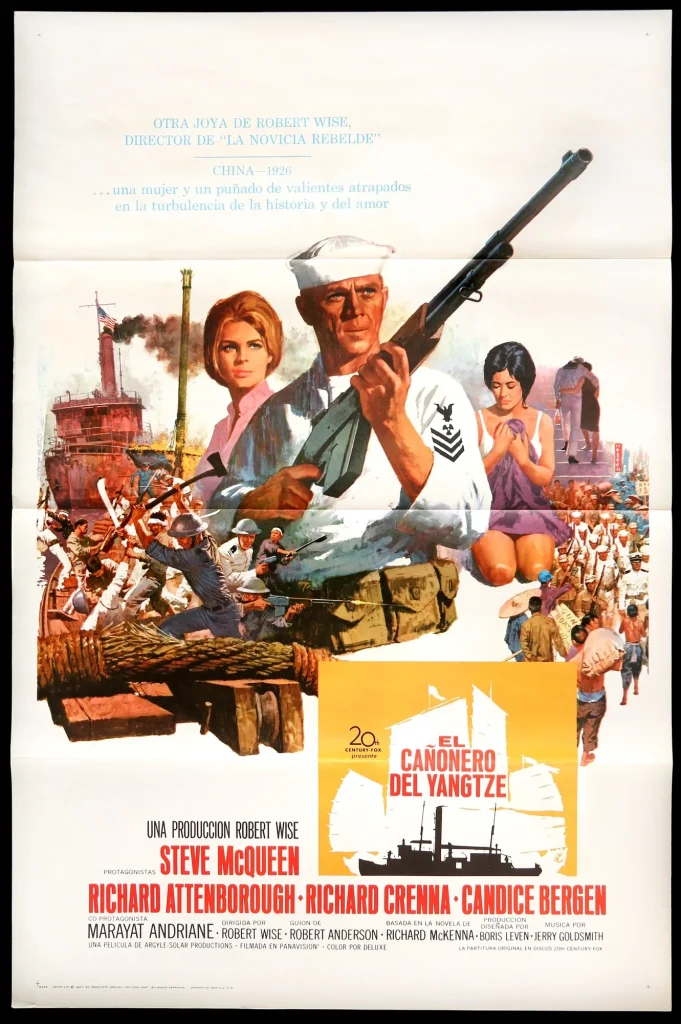

He was known by his first name only, and used his mother’s surname Iwamatsu. In addition to his 1976 Best Actor (Musical) Tony nomination, the native of Kobe, Japan, was also Academy Award nominated for “The Sand Pebbles.”

He also starred in the title role in the 1992 Broadway play Shimada.

The cause death, according to wire reports, was esophageal cancer. Mako was 72 and is survived by his wife, Suzie, two daughters, Mimosa and Sala, and a sister Momo Yashima. Per his wishes, there will be no funeral or memorial service.

Mako moved to the United States to join his parents, who had emigrated there earlier, when he was 15. After his service in the U.S. military, he embarked upon a career in film and theatre, and studied at the Pasadena Community Playhouse in California.

Mako founded the Asian-American theatre company East West Players, in Los Angeles. Over the years, he directed, designed and acted in East West productions. Mako directed several plays at EWP in the past several years, and was to have made his stage return as an actor in Motty-chon by Perry Miyake on the occasion of EWP’s 40th Anniversary in May 2006. The production was cancelled in the third week of rehearsal as Mako had to start treatment immediately for his health condition.

As a teacher and acting icon, he was an inspiration to Asian-American actors.

“Personally, Mako helped open my eyes as a young artist just graduating from USC,” East West Players’ producing artistic director Tim Dang told Playbill.com. “He made me aware of the lack of opportunities in the industry and the valiant work that was ahead. He wanted to make sure that I was tough enough to survive in an industry where 80 percent of artists are unemployed and that percentage is even worse if you are an artist of color.”

Mako’s last public appearance for East West Players was on the occasion of its 40th Anniversary Gala on April 10, 2006 where he presented the Rae Creevey Award to Emily Kuroda and Alberto Isaac.

Dang added, “It’s a very sad time for East West Players but also for Asian American artists. We’ve lost many of our pioneers in the last few years. And Mako’s passing will affect us for a long time but I know that Mako would want us to keep the movement moving forward.

“With Mako’s passing, there is a great feeling of loss in the Asian Pacific artist community. We have lost a pioneer who helped pave the way for all of us trying to make a career in the arts and the entertainment industry. East West Players is deeply grateful for the passion, the artistry and the activism that Mako displayed over the many decades as artistic director, director and performer. If it wasn’t for Mako, none of us would be here.”

Mako’s film credits include “Memoirs of a Geisha,” “Conan the Barbarian,” “Seven Years in Tibet,” “Pearl Harbor,” “The Green Hornet,” “Rising Sun,” “The Ugly Dachshund” and more.

In “The Sand Pebbles,” for which he was Oscar nominated in the category of Best Supporting Actor, he played a submissive engineer, Po-Han. It was his first film (the Disney picture, “The Ugly Dachshund” was released the same year, 1966). Mako was also featured as a guest on many television shows, including “F Troop,” “Hawaii Five-0,” “Kung Fu” and “The West Wing.”

His sonorous performance in Pacific Overtures was captured on the original cast recording.

Tom Vallance’s “Independent” obituary:

The Japanese American actor Makoto Iwamatsu (usually billed simply as “Mako”) was a skilled performer who won nominations for both an Oscar and a Tony, and was equally renowned for the efforts he made to end stereotypical casting and treatment of Asian performers. In 1965 he co-founded the United States’ first Asian American theatre company, East West Players, housed initially in a church basement and now based in the Little Tokyo district of Los Angeles. He was, says the company’s current artistic director, Tim Dang, “sort of the godfather of Asian American theatre”.

Born in Japan in 1933, Mako was raised by grandparents after his mother and father moved to New York to study art. Because they settled on the East Coast, they were not interned during the Second World War, but given work in the US Office of War Information; later they were given residency. Mako joined them at the age of 15 and studied at the Pratt Institute in New York with plans to become an architect, but a friend’s request that he design the sets and lighting for an off-Broadway children’s play began a love of theatre. “That’s when the trouble began,” he said. “I was out of class so much that I lost my draft deferment.”

After two years’ military service, he moved to California, where he studied theatre at the Pasadena Playhouse, and in 1956 he became a naturalised citizen. He made his screen début with a bit role in Never So Few (1959), a Burma-set war film starring Frank Sinatra.

Shortly after founding East West Players, he was cast in Robert Wise’s impressive if overlong epic The Sand Pebbles (1966), starring Steve McQueen as a sailor assigned to a US Navy gunboat patrolling the Yangtze River in 1926. Put in charge of an engine room manned by Chinese workers, he alienates the crew by dismissing the Chinese, who are doing all the on-board duties while the American sailors live a life of ease. McQueen retains just one Chinaman, Po-han, played by Mako, whom he befriends. He later teaches Mako boxing tricks that enable him to win a fight against a brawny American sailor in order to defend the honour of a Chinese girl forced to work in a brothel.

In some respects, Mako’s role was the sort he was campaigning against, that of a subservient Chinese “coolie” who spoke pidgin English, called his bosses “master”, and expired heroically, but he brought warmth and dignity to the role and was deservedly nominated for the Academy Award.

George Takei, who played “Sulu” in Star Trek, said, “He was one of the early truly trained actors who was able to take stock roles, roles seen many times before, and make an individual a live and vibrant character.”

Mako’s role as the Reciter in Pacific Overtures (1976) displayed that vibrancy to Broadway audiences, who responded rapturously to his star performance. The musical, with libretto by John Weidman and an ambitious score by Stephen Sondheim built around a quasi-Japanese pentatonic scale, examined the events surrounding the opening of Japan to the West in 1853 due to the threatening presence of Commodore Perry’s four American warships. Told from a Japanese point of view and employing an all-Asian cast, it used devices from Kabuki theatre, including having the women’s parts played by men, with the whole linked by the Reciter (Mako) who presides over, takes part in, and comments throughout the show.

Mako’s charisma and authority largely inspired the word of mouth that kept the show, not a hit, running for six months, though he offered to leave during rehearsals when he despaired of ever mastering his demanding opening number, “The Advantages of Floating in the Middle of the Sea”. “It was particularly hard for him because he was an immigrant,” said Takei. “There was the linguistic challenge.”

The show’s original cast album displays Mako’s mastery of that difficulty – he even at one point has to mimic some of the British admiral’s Gilbertian patter: “The man has come with letters from Her Majesty Victoria, as well as little gifts from Britain’s various emporia.” He also took part in the number that Sondheim has declared his personal favourite of all his songs, “Someone in a Tree”, in which a Japanese warrior, an old man, and the man’s childhood self describe the negotiations at the historic treaty-house meeting between the Japanese and Americans.

Mako’s performance won him a Tony nomination as best actor in a musical, though he lost to George Rose as Doolittle in a revival of My Fair Lady.

As artistic director of East West Players, he trained not only generations of actors but also playwrights (“Unless our story is told to other people, it’s hard for them to understand where we are”) and he staged plays by Shakespeare and Chekhov as well as contemporary works. In 1981, when national discussions were about to start on the subject of reparation for Japanese Americans interned during the Second World War, Mako devoted the whole season to works on the subject. Takei, who helped with funding during the group’s earlier days, said,

In part the Asian American community still had the immigrant values of encouraging their children to go into medicine, law, engineering. They were not only not supporting their children who evidenced talent in performing arts, but outright discouraging them. East West Players gave those youngsters an opportunity to practise their craft, but at the same time developed an audience that supported our performers.

Mako appeared on screen as the Wizard with Arnold Schwarzenegger in Conan the Barbarian (1982) and its sequel Conan the Destroyer (1984), and he was a Singaporean in Seven Years in Tibet (1997) with Brad Pitt. In Pearl Harbor (2001) he was Admiral Yamamoto, and in 2005 he had a cameo role in Memoirs of a Geisha.

He also lent his distinctively raspy voice to animated features, particularly on television – he was the evil demon Aku in the animated series Samurai Jack, also enacting a parody of that character, called Achoo, in Duck Dodgers, and he was the voice of Uncle Iroh in Avatar: The Last Airbender. Prolific acting work on television included guest spots in I Spy, Fantasy Island, M*A*S*H, Quincy and Frasier.

Last year he was a guest star on an episode of The West Wing entitled “A Good Day”, in which he played an economics professor and former rival of President Bartlet. Before his death from cancer, he had been announced to provide the voice of Splinter in the newest Teenage Mutant Turtles film.

In 1989 differences with the board of directors caused Mako to break with East West Players, though in the months before his death he was preparing to appear with his wife, actress Shizuko Hoshi, in one of their productions. “Of course,” said Mako to the Los Angeles Times in 1986, “we’ve been fighting stereotypes from day one at East West. That’s the reason we formed: to combat that and to show we are capable of more than just filling the stereotypes – waiter, laundryman, gardener, martial artist, villain.”

Tom Vallance

The comedian and satirist Mort Sahl, who has died aged 94, was a combination of Lenny Bruce and Bob Hope – with a little Will Rogers thrown in. Like Bruce, Sahl was a product of the 1950s. Like Hope, he was as much a reporter and commentator on the events of the day as a morning newspaper. And like Rogers, who took the US by the heartstrings during the days of the Great Depression, he would walk on stage with one of those papers in his hand and proceed to take a famous figure to task.

Rogers just made jokes about the people in the news, but Sahl specialised in demolishing them. Different from Hope, who employed an army of ghostwriters, Sahl wrote all his own material – and not just for himself; for a while he was President John F Kennedy’s principal joke writer. To much surprise, he later became a close friend of Ronald Reagan.

Unlike Bruce, who used to say that Sahl was his inspiration, he did not shock with obscenities and the drug culture seemed to be foreign to him. Nevertheless, he had the effect of a heat-seeking missile on his targets. When American politicians were in trouble, they had to take cover whenever Sahl appeared on stage or on a television talk show. Kennedy said he liked Sahl because he admired a man who was “in relentless pursuit of everybody”.

Born in Montreal, he was the son of Harry Sahl, a Jewish-American court reporter who had gone to Canada to write plays and go into business. When this failed, he took his wife, Dorothy, and son, Morton, back to the US and became an administrator for the FBI. The younger Sahl would later become the subject of a considerable FBI file about his suspected communist leanings. Nothing stuck, however, and his political affiliations were never clear.

At school in Los Angeles, he was a member of the officer cadet corps. He was drafted into the US air force soon after the second world war and stationed in Alaska, where he worked on the base newspaper. He then went to the University of Southern California to take a degree in city management. Before long, his only connection with that worthy subject would be lambasting it from the stage of a smoke-filled club or a small theatre – although usually his targets were larger.

He almost starved trying to sell his writing before he arrived at the hungry i nightclub in San Francisco in the early 50s, but by the end of the decade and in the early 60s, he was the favourite nightclub entertainer in the more sophisticated parts of New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. What many of the well-heeled and well-known patrons liked about him was that he had no more respect for the leftwing than for the establishment on the right.

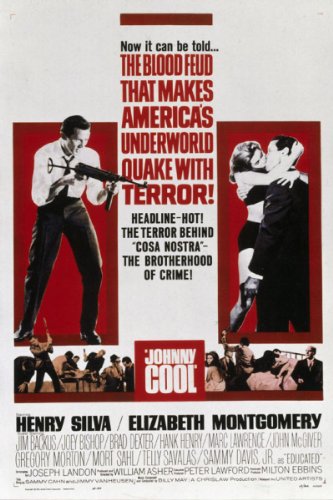

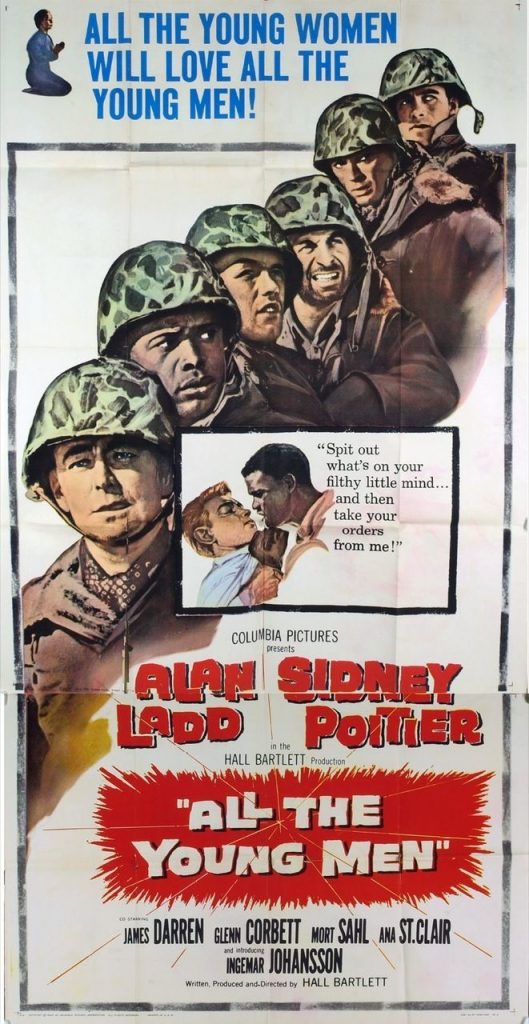

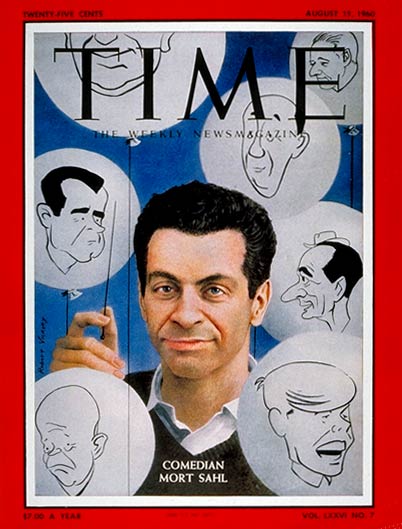

He was one of the first satirical comedians to make LP records and sell them, the first being At Sunset, recorded in 1955. He became such an influential figure that Time magazine devoted one of its celebrated cover features to him, describing him as “Will Rogers with fangs”. Sahl also wrote screenplays and occasionally appeared in films himself, including Johnny Cool (1963), Inside the Third Reich (1982) and Nothing Lasts Forever (1984).

For a while in the 60s, his fame and appeal began to wane, but Sahl regarded it as his duty to continue to attack whatever he believed needed attacking. The assassination of Kennedy in 1963 was a landmark: he regarded the president’s killing as he would the death of a close relative. When the Warren commission declared that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone, Sahl took it as a personal affront and campaigned to have the findings reversed.

The Vietnam war was perfect grist for the mill of his talent; people began to want to hear what he said about it, and he guested again on the top talk shows. But his stage work faded until the late 80s – when, for the first time, he had a four-week run at a Broadway theatre. He came out on to a bare stage, as he always did, in a pair of slacks and a V-neck sweater. But there was the inevitable folded newspaper and the comment on the world around him.

“Washington couldn’t tell a lie,” he said, “Nixon couldn’t tell the truth and Reagan couldn’t tell the difference.” Although he was a frequent guest at the White House during the Reagan years, the president remained a target.

He would skewer politicians of all parties, latterly including Barack Obama and Donald Trump. Asked what his principal philosophy was, he would say “I am allergic to majorities” and he was known for the stage catchphrase: “Are there any groups I haven’t offended?” In 2004 he described himself as “a disturber”.

When he talked about retirement, he would say: “I’d be glad to relinquish the reins and go on and do something useful … but I can’t seem to clean up the town.” He carried on performing once a week until prevented by the pandemic.

The New York Post critic Clive Barnes once wrote of Sahl: “The real joy of the man, and his show, is the quickness of his mind and his wonderful sense of nonsense. Forget that the man is clever. Merely think of him as the funniest guy in town.”

Sahl was married and divorced four times. His son, Mort Jr, from his second marriage, to China Lee, died in 1996.

Morton Lyon Sahl, comedian, born 11 May 1927; died 26 October 2021