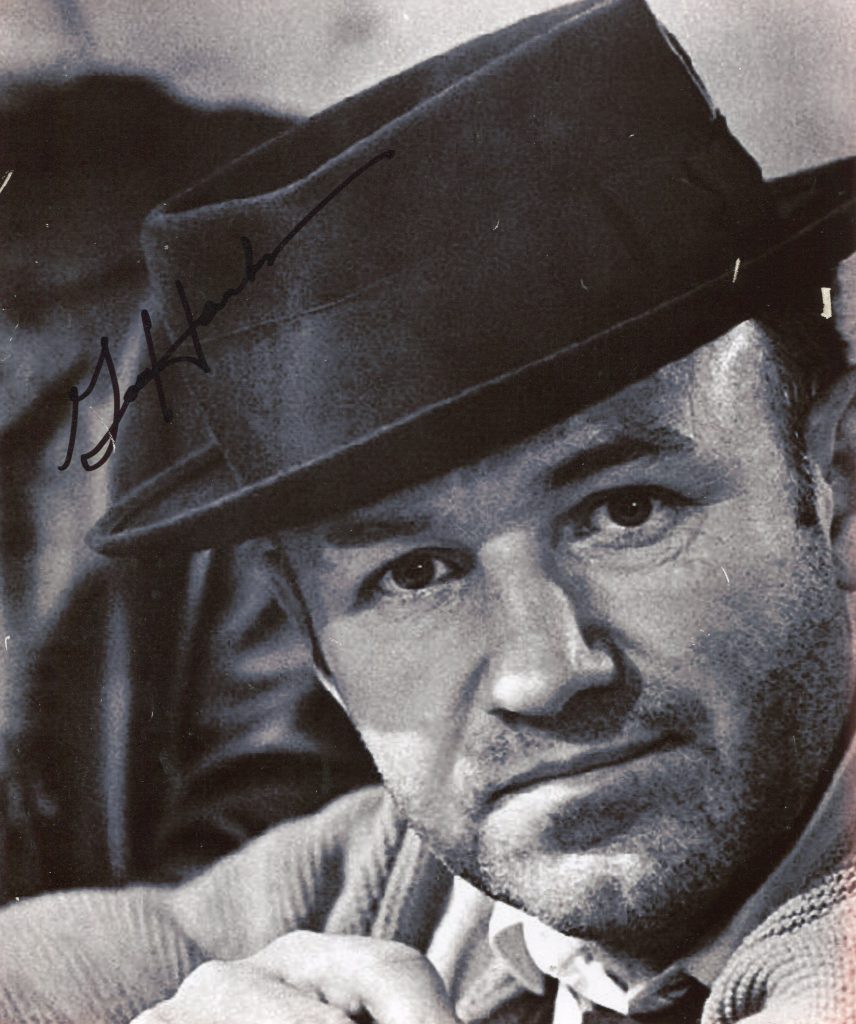

“‘Dependable’ was a good word to use about Gene Hackman as a supporting actor (and John Simon did, about his performance in “Downhill Racer”). And then, by virtue of a role turned down by at least seven other actors and it’s accompanying Oscar, he became a star. His acting, if anything, became more finely honed – but stardon brought his problems. As Bart Mills wrote in London in ‘The Guardian’ : It’s not easy being a star who knows he has no right to be a star. Gene Hackman never got near the honey pot till he was past 40. He has about as muich sex appeal as your balding brother-in-law. He dreams fondly of retiring. He’s aware that somebody somewhere made a big mistake.. The mistakes, as it happened, were all his”. – David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars – The International Years”. (1972).

Hackman was one of the giants of the U.S. screen from the late 1960’s into the 1990’s. He was born in 1930 in San Bernadino, California. He came to fame in a supporting role

in 1967 in “Bonnie & Clyde”. He won an Oscar in 1971 for “The French Connection” and another in 1990 for Clint Eastwood’s “The Unforgiven”. A great, great actor now sadly retired.

One of the most versatile and well-respected actors in American cinema history, Gene Hackman enjoyed a productive career that spanned over six decades, encompassing exquisite performances on stage and in feature films. Once voted by his acting school classmates as the least likely to succeed, Hackman essayed some of filmdom’s most memorable characters, a few of which earned the gruff, but sensitive actor several Academy Award nominations. Beginning as a reliable character player on stage, Hackman emerged as an unlikely hero of the counterculture with a bombastic turn in Arthur Penn’s seminal “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967). Just a few years later, he secured himself an Oscar for Best Actor with his tough-guy performance as the unforgettable Popeye Doyle in “The French Connection” (1971). Hackman again delivered the goods in Francis Ford Coppola’s paranoid thriller, “The Conversation” (1974) and followed through as the comically maniacal Lex Luther in “Superman: The Movie” (1978). Though he entered a premature retirement brought on by his exhaustive work schedule, Hackman returned to the fore in Warren Beatty’s “Reds” (1981) and entered into what proved to be the busiest part of his career, which culminated in an Academy Award nomination for “Mississippi Burning” (1988) and a Best Supporting Actor win for “Unforgiven” (1992). After portraying a sleazy B-movie producer in “Get Shorty” (1995) and the rascally patriarch of a dysfunctional family in “The Royal Tenenbaums” (2001), Hackman drifted off into an unofficial retirement that allowed him time to nurture his writing career while leaving behind a remarkable legacy.

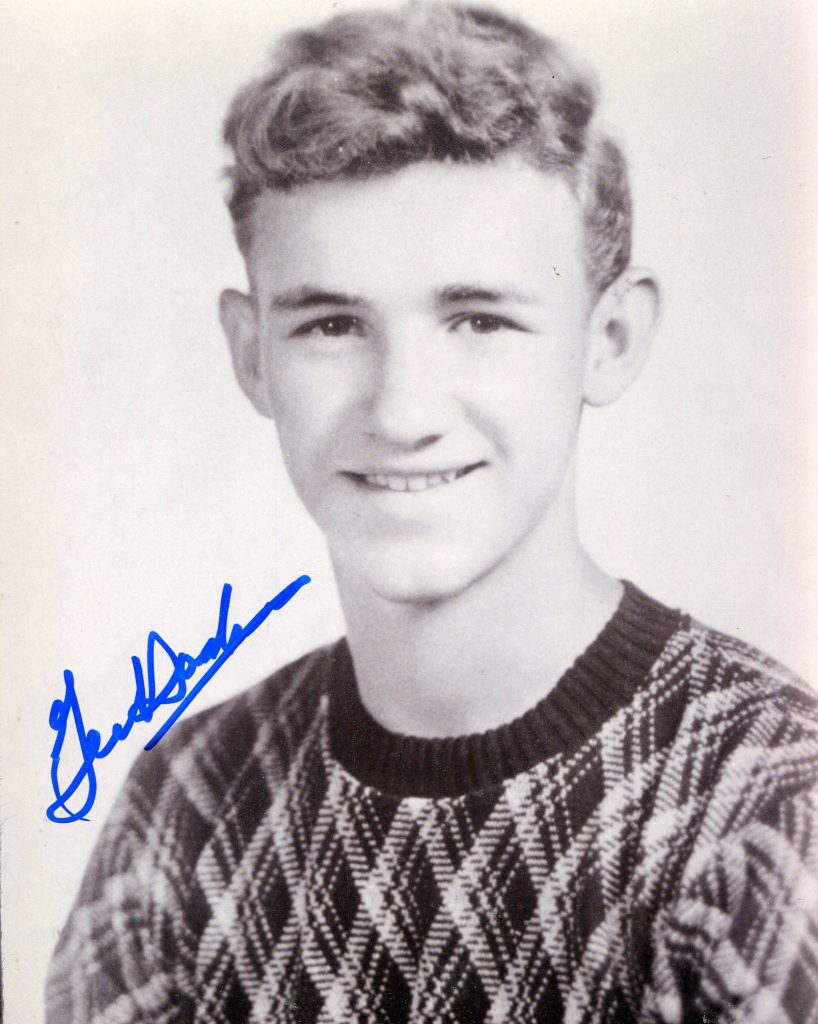

Born on Jan. 30, 1930 in San Bernardino, CA, Hackman endured a nomadic childhood with his father, Eugene, and his mother, Lyda, before finally settling in Illinois, where he was raised by his maternal grandmother, Beatrice. Unchallenged by school, he dropped out at age 16 and lied about his age to enlist in the U.S. Marines. Trained as a radio operator, Hackman served in China where his radio background helped land him work as a disc jockey. While suffering from two broken legs following a 1950 motorcycle accident, Hackman decided to pursue a career in radio, moving to New York City after his discharge to study at the School of Radio Technique. Throughout the early part of the decade, he worked his way across America’s heartland, developing his resonant vocal abilities as a radio announcer at various stations. Fast approaching 30, Hackman decided to translate his radio experience into an acting career, enrolling at the famed Pasadena Playhouse, where he was dubbed by an instructor “least likely to succeed,” an honor he shared with fellow classmate Dustin Hoffman. Despite making his stage debut with a supporting role in “The Curious Miss Caraway” (1958), Hackman was asked to leave the Pasadena Playhouse.

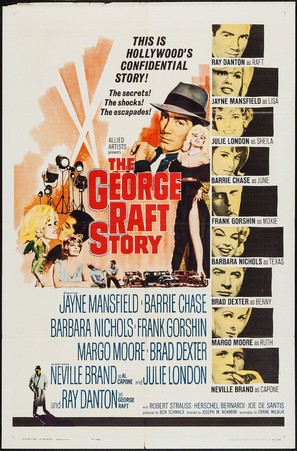

With nowhere else to turn, Hackman moved back to New York City, where he struggled alongside Hoffman and Robert Duvall to try to succeed despite assurances of failure from his old classmates and instructors. He flourished under the tutelage of George Morrison, a former instructor at the Lee Strasberg Institute, who trained the aspiring performer in the famed ‘Method’ approach to acting. Meanwhile, Hackman made his stage debut in “Chaparral” (1958) and began finding employment in various small screen productions like the “U.S. Steel Hour” (ABC/CBS, 1953-1963) and the premiere episode of the courtroom drama, “The Defenders” (CBS, 1961-65). A few years after joining the improvisational troupe, The Premise, Hackman truly arrived as a stage actor with a supporting performance opposite Sandy Dennis in a Broadway production of “Any Wednesday” (1964). That same year, he had his first substantial film role, playing the romantic rival for an occupational therapist (Warren Beatty) who falls for a wealthy mental patient (Jean Seberg) in the downer psychological drama, “Lilith” (1964).

When it came time to cast the role of Buck, the older brother of outlaw Clyde Barrow (Warren Beatty), in the seminal counterculture crime drama “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967), Beatty remembered Hackman from “Lilith” and offered him the role. Bringing a Brandoesque spin to the role, Hackman turned what could have been just a murderous rube into a character infused with a righteous innocence, which helped earn the actor who was once voted least likely to succeed his first Academy Award nomination as Best Supporting Actor. He was excellent as the driven Olympic coach in the documentary-like “Downhill Racer” (1969) and picked up a second Best Supporting Actor Oscar nod as he mined the autobiographical parallels of a son who cannot communicate with his dad in “I Never Sang for My Father” (1970). The following year brought him a once-in-a-lifetime role, playing the tough, uncompromising New York City narcotics cop Popeye Doyle in “The French Connection” (1971). While the film was perhaps best remembered for a brilliantly staged car chase with Doyle going after a runaway subway, Hackman managed not to be overshadowed, skillfully crafting a warts-and-all portrait of a vulgar sadist. Accolades rained on Hackman, who capped a banner year with an Academy Award for Best Actor.

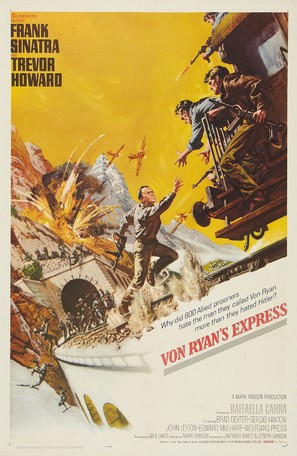

Now firmly established as a leading man, Hackman began to undertake a series of roles that further demonstrated his range and versatility. He proved effective as a crusading preacher and de facto leader of a group of survivors of a sea disaster in the enjoyably cheesy adventure yarn, “The Poseidon Adventure” (1972), and effectively partnered with Al Pacino in the buddy road movie “Scarecrow” (1973). Meanwhile, director Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Conversation” (1974) offered one of the richest characterizations of his long career, in which he played a surveillance expert whose personal involvement in one of his cases leads to a plunge into paranoia and suspicion. Hackman next delivered a short, but well-remembered cameo role as a blind hermit who fumbles his efforts to provide aid and comfort to the misunderstood monster (Peter Doyle) in Mel Brooks’ horror spoof, “Young Frankenstein” (1974), starring Gene Wilder and Teri Garr. For the first time, audiences were able to see Hackman’s sharp comic abilities, which to that point were woefully unexplored. Following starring roles in the Western “Zandy’s Bride” (1974) and the noir crime drama “Night Moves” (1975), Hackman reprised Popeye Doyle, who tracks down the escaped Frog One (Fernando Rey) to Marseilles, in the mediocre, but still well-acted sequel, “The French Connection II” (1975).

By the mid- to late-1970s, Hackman’s career went into a bit of a slide, following starring turns in such underwhelming movies like “March or Die” (1977) and “The Domino Principle” (1977). By the time he was showcasing his high camp villain Lex Luthor in “Superman” (1978), Hackman had prematurely announced his retirement after nearly non-stop work that had left him physically and emotionally drained. Spending his time painting in a West Los Angeles apartment, Hackman was eventually pulled back into the game by old friend Warren Beatty, who convinced the actor to play magazine editor Peter Van Wherry in the epic historical drama “Reds” (1981). While he was miscast opposite Barbra Streisand in the triangular romantic comedy “All Night Long” (1981), he was right at home in the action-adventure “Uncommon Valor” (1983) and the gripping political thriller “Under Fire” (1983). Hackman brought depth and conviction to his performance as a straying husband undergoing a mid-life crisis in “Twice in a Lifetime” (1985), perhaps in part inspired by his 1982 divorce from first wife, Faye Maltese. Re-energized after his self-imposed exile, Hackman went on to etch several memorable characterizations in the 1980s, including a small-town high school basketball coach in “Hoosiers” (1986) and a cold-hearted Secretary of Defense in the thriller “No Way Out” (1987).

Following a reprisal of Lex Luther in the unnecessary “Superman IV: The Quest for Peace” (1987), Hackman delivered a searing performance as a good ole boy FBI agent investigating the murders of civil rights workers in the 1960s-era drama, “Mississippi Burning” (1988), for which he picked up another Academy Award nomination for Best Actor. As he entered the 1990s, Hackman remained exceptionally busy, churning out a wide variety of roles. After playing a practical-minded cop who teams up with a partner (Dan Aykroyd) suffering from multiple personality disorder in the miserable “Loose Cannons” (1990), he was a lawyer who enters the courtroom opposite his attorney daughter (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) in Michael Apted’s “Class Action” (1991). Though surgery in 1990 for heart problems provoked another hiatus, Hackman roared back with another fascinating role, playing sadistic, but smiling sheriff Little Bill Daggett in Clint Eastwood’s revisionist Western “Unforgiven” (1992). Infusing the effective lawman with a streak of decency, the actor sketched a character that was profoundly ambiguous; one that could be either heroic or villainous. Critics and audiences embraced the film and Hackman’s character and he earned not only stellar reviews but numerous prizes, all of which was capped by a second Oscar, this time as the year’s Best Supporting Actor.

Healthy and in-demand, Hackman embarked on another round of seemingly non-stop roles. While Sydney Pollack cast him as the burnt-out lawyer and mentor to Tom Cruise who is powerless to help his protégé in “The Firm” (1993), the actor displayed a sudden fondness for Westerns. He was a sympathetic general in “Geronimo: An American Legend” (1993), the moral compass of “Wyatt Earp” (1994) as the family’s patriarch, and in an almost-spoof of Little Bill, played a gunslinger in the loopy “The Quick and the Dead” (1995). Loosening up a bit, Hackman displayed his assured comedic gifts as a schlock horror filmmaker who runs afoul of a Mafia boss (Dennis Farina) tracking down a loan collector (John Travolta) who embarks on a movie career in “Get Shorty” (1995). After a turn as a conservative politician who plays straight man – on more than one level – to Robin Williams and Nathan Lane in “The Birdcage” (1996), Hackman began to display a darker side, playing a sinister surgeon in “Extreme Measures” (1996) and a racist killer on death row in “The Chamber” (1996). He excelled in his next two performances, playing a U.S. President embroiled in a murder investigation in “Absolute Power” (1997) and a renegade NSA agent in the thriller “Enemy of the State” (1998), a role that was an overt nod to his performance in “The Conversation.”

Having done all he could do in Hollywood, Hackman entered the world of publishing with his first novel, Wake of the Perdido Star (1999), which he co-wrote with author Daniel Lenihan. While 1999 marked the first year he failed to appear in a single feature film, Hackman returned the following year with a turn in “The Replacements” (2000), playing the NFL coach of a rag-tag group of players filling in for a striking team. Later he was featured in “Under Suspicion,” Stephen Hopkins’ nervy reworking of the French film “Garde a vu” (1982), playing a wealthy attorney suspected of rape and murder. After an uncredited cameo in “The Mexican” (2001), he had a charming role as a billionaire reeled in by mother-daughter beauties (Sigourney Weaver and Jennifer Love Hewitt) in the unremarkable con-women comedy “Heartbreakers” (2001). Next he headed the impressive cast of David Mamet’s low-key thriller, “Heist” (2001), with a note-perfect and effortless performance that was tinged with both bravado and vulnerability as an almost untouchable veteran master thief. Hackman followed up with a role as a steely admiral who risks his career when he puts people over politics in an effort to save a maverick navigator (Owen Wilson) shot down in Bosnia in “Behind Enemy Lines” (2001).

Though he was a steady presence on the big screen, Hackman’s career began to show signs of slowing down. While at the time most were unaware, the veteran actor was on his way to retirement. He did, however, have one more great performance in him, which he delivered in Wes Anderson’s droll family dramedy, “The Royal Tenenbaums” (2001), in which he played the titular patriarch of a dysfunctional family of geniuses (Ben Stiller, Gwyneth Paltrow and Luke Wilson). Anderson admitted to creating the funny, but ultimately endearing role for Hackman, though the actor had vocally opposed such endeavors in the past. Any objections were quickly silenced when the actor won a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy. After receiving a special Cecil B. DeMille Award at the Golden Globes ceremony in 2003, Hackman was next seen on screen in “Runaway Jury” (2003), playing Rankin Fitch, a high-priced and morally bankrupt jury consultant who stops at nothing to control the outcome of a crucial trail verdict. For the first time in his career, Hackman played opposite his friend and fellow actor voted least likely to succeed, Dustin Hoffman.

In the political satire “Welcome to Mooseport” (2004), Hackman played a former U.S. president who runs for mayor of a small Maine town against a local hardware store owner and plumber (Ray Romano). Not his best work by any stretch, “Mooseport” wound up being the final film Hackman appeared in to date, marking the start to his unofficial retirement. Hackman confirmed on a 2004 airing of “Larry King Live” (CNN, 1985-2010) that he had no projects lined up and believed that his acting career was indeed over. Meanwhile, he continued to co-author novels with Daniel Lenihan, including Justice for None (2006) and Escape from Andersonville (2009), which dramatized a prison break from Fort Sumter during the Civil War.

By Shawn Dwyer

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.