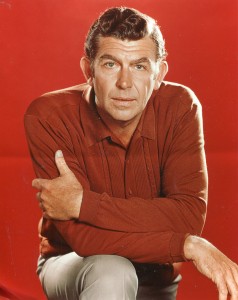

Peter Sellers wasone of the great film comics of all time. He was born in Portsmouth in 1925. He began his career with ‘The Goons’ on BBC Radio. His first film was “Penny Points to Paradise” in 1951. He had a major role in the Ealing classic of 1955, “The Ladykillers”. He made many terrific movies in the the U.K. in the late 1950’s including “The Smallest Show on Earth” and “The Naked Truth”. In 1963 he had enormous success with “The Pink Panter”. He went to Hollywood soon therafter to make “Kiss Me Stupid” but suffered a heart attack and was replaced by Dean Martin. After recovering he went on to make “What’s New Pussycat” and “The Wrong Box”. One of his last roles was “Being There” and he died of another heart attack in 1980 at the age of 54.

TCM overview:

One of the most accomplished comic actors of the late 20th century, Peter Sellers breathed life into the accident-prone Inspector Clouseau in “The Pink Panther” (1963) and its three sequels, as well as such classics as “Lolita” (1962), “Dr. Strangelove” (1964), “The Party” (1968) and “Being There” (1979). The son of English vaudevillians, his ability to completely transform himself into outrageous comic characters received its first showcase on the legendary radio series “The Goon Show” in the 1950s. Film roles in the 1950s and 1960s were devoted to his knack for mimicry of accents and character types, with Stanley Kubrick’s “Lolita” and “Dr. Strangelove” underscoring his talent for drama as well. His best-known role of Inspector Clouseau surfaced in 1963, and he would return, sometimes reluctantly, to the franchise throughout his life before scoring a personal triumph as the simple-minded gardener who influences the Presidency in Hal Ashby’s “Being There” (1980). Off camera, Sellers could be cold, cruel, even unstable, but when the cameras were rolling, he showed a dedication to performance and humor that made him one of the greatest inspirations to comedians and film fans for decades.

He began life as Richard Henry Sellers on Sept. 8, 1925 in the seaside resort town of Southsea, in Portsmouth, England. His family, who were performers on the British vaudeville circuit, bestowed a particularly morbid nickname upon their son: Peter was the name of a brother who did not survive birth. He took up his family’s profession at an early age, dancing and singing alongside his mother in stage shows when he was just five years old. He became skilled at a variety of talents, including drums, banjo and ukulele, and for a while, he toured as a drummer with various jazz bands. Sellers was also an expert mimic, which he put to excellent use during his service as an airman with the Royal Air Force during World War II. He frequently impersonated his superior officers as a way to gain access into the Officers’ Mess, and made them part of his performances with the Entertainments National Service Association, which put on plays and skits for British troops. His knack for mimicry also served him well in the years after his discharge in 1948. Sellers supported himself by performing stand-up comedy and celebrity impressions on the variety theater circuit, and at one point, secured a meeting with BBC producer Roy Speer by pretending to be radio star Kenneth Horne. The ruse clearly worked, as the 23-year-old Sellers was soon granted an audition, which lead to a role on the popular radio comedy “Ray’s a Laugh,” starring comedian Ted Ray. Audiences had their first glimpse of Sellers’ astonishing voice talent on the series, which allowed him to play everything from an obnoxious little boy to a bizarre older woman.

During this period, Sellers was also performing in an informal group with comics Spike Milligan and Michael Bentine and singer Harry Secombe. The quartet, who dubbed themselves the Goons, recorded their antics at a local pub, and the tape made its way into the hands of a BBC producer, who granted the quartet their own radio series. “The Goon Show” premiered in 1951 and became a massive hit with British audiences, thanks to its surreal humor which parodied traditional radio drama with absurd leaps in logic. Each episode was filled with countless bizarre characters, many of which were voiced by Sellers, including the program’s chief villain, Hercules Grytpype-Thynne; the hapless scoutmaster Bluebottle; the cowardly, flatulent Major Bloodnok (who was based on many of Sellers’ superior officers), and many others. On more than one occasion, Sellers was called upon to voice all of Milligan’s characters as well, and at times, carry out complete conversations between two or more people.

The popularity of the Goons’ radio program led to a few abortive attempts at television series, including “The Idiot Weekly, Price 2d” (ITV, 1956), but most filmed efforts were unable to match the stream of consciousness that comprised their recorded efforts. More successful were the Goons’ comedy LPs and novelty songs, as well as a quartet of films – the feature length “Let’s Go Crazy” (1951), which marked Sellers’ screen debut, “Penny Points to Paradise” (1951), “Down Among the Z Men” (1952), and the shorts “The Case of the Mukkinese Battle Horn” (1956) and “The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film” (1959). The latter, directed by Sellers and Richard Lester, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Live Action Short, and also served as the impetus for the Beatles – all dedicated Goons fans – to hire Lester to direct “A Hard Day’s Night” (1964). The Goons were also acknowledged influences on the members of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, Eddie Izzard, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy author Douglas Adams, Peter Cook, the Firesign Theater and countless British and American television comedies.

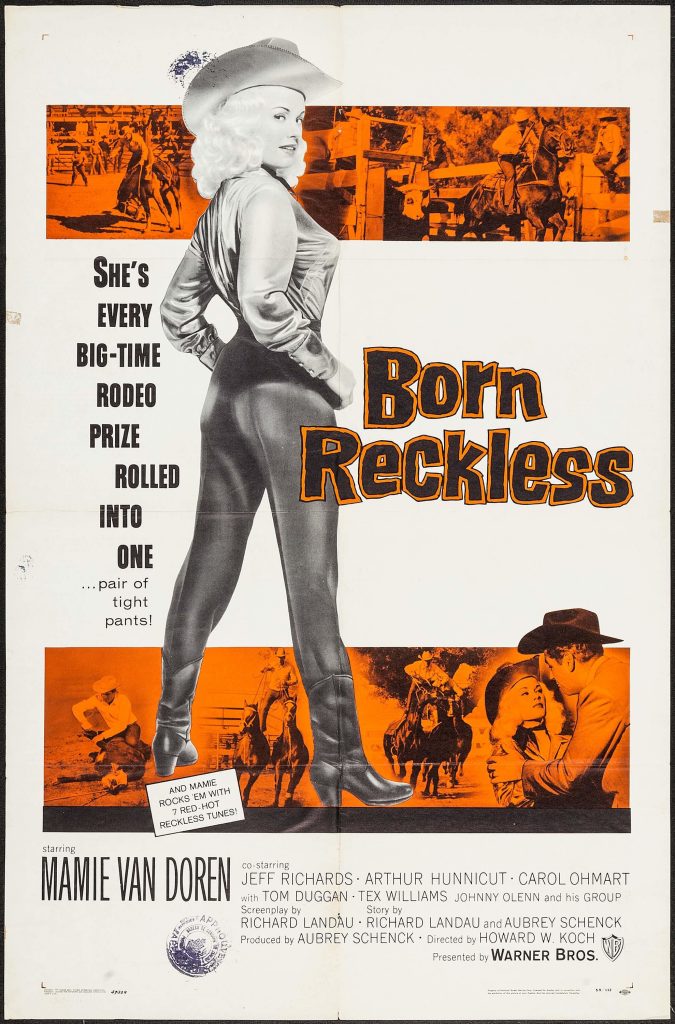

In 1954, Sellers began branching out on his own as a supporting player in feature comedies. He quickly established himself as versatile a performer on screen as he was over the radio airwaves, with richly varied characters in some of the greatest British comedies of the late 1950s and early 1960s. He was the nervous Teddy Boy that joined Alec Guinness’s inept criminal crew in Alexander Mackendrick’s “The Ladykillers” (1955), an obsequious game show host in “The Naked Truth” (1957), a baffled military officer in Val Guest’s “Up the Creek” (1958), and most impressively, three roles in “The Mouse That Roared” (1959), including the addled Duchess of the tiny European nation of Fenwick, which declares war on – and defeats – the United States. Several of these pictures were international successes, especially in America, which brought Sellers to the attention of Hollywood. In 1958, he made his stateside debut in “tom thumb” (1958), fantasy director George Pal’s musical adaptation of the Brothers Grimm fairy tale about a tiny hero who outwits a pair of thieves (Sellers and Terry-Thomas).

Sellers’ stature as a film star grew in the 1960s, thanks to several key films. “Never Let Go” (1960) was a thriller that afforded him a rare opportunity to play a straight role as a murderous car dealer, while “I’m All Right Jack” (1959) proved he could bring pathos to his comic roles. His turn as a Communist shop steward who becomes a reluctant strike leader in the latter film earned him a BAFTA for Best Actor in 1959. However, it was Stanley Kubrick’s controversial adaptation of “Lolita” (1962) that made him an international star. His protean nature was given full reign as Clare Quilty, the decadent playwright who attempts to lure Sue Lyon’s teenage Lolita into his depraved world, prompting his murder by Humbert Humbert (James Mason). Kubrick’s version expanded the role considerably, allowing Sellers to don several disguises and accents throughout, including a Germanic doctor, Zempf, who foreshadowed Sellers’ turn as Dr. Strangelove two years later. For his efforts, Sellers was critically acclaimed, as well as a Golden Globe nominee for Best Supporting Actor.

In 1963, Sellers made his first appearance in his most iconic role – that of Chief Inspector Jacques Clouseau in “The Pink Panther.” Fiercely dedicated to fighting crime and upholding the dignity of France, Clouseau is also wildly accident-prone, egotistical to a fault and burdened with an impenetrable accent that transformed English into a wholly unknown language. A supporting character in “Panther,” which was intended as a comic caper series devoted to star David Niven’s gentleman jewel thief, it was Sellers that captured audiences’ attention, and led to a long and tumultuous series of films. The second in the series, “A Shot in the Dark” (1964), followed a year later with Clouseau now the central character. It too was a success, but the relationship between Sellers and director Blake Edwards deteriorated to such a degree that the pair refused to work together again until 1968’s “The Party.” A third Clouseau film, “Inspector Clouseau” (1968), continued the franchise with Alan Arkin in the title role, but it was not a success, prompting MGM to urge Sellers and Edwards to patch up their differences and return to the series for 1975’s “Return of the Pink Panther.”

Clashes such as the one with Edwards were not uncommon for Sellers during his career. In both Europe and America, he soon developed a reputation as a difficult performer, prone to lashing out at castmates over perceived slights. His personal life was also marked by moments of astonishingly casual cruelty towards his spouses and children. His first marriage, to Anne Howe, ended in a difficult divorce that may have been prompted by an affair with actress Sophia Loren; his second marriage, to actress Britt Ekland, was marked by domestic violence spurred by allegations of infidelity. Biographers surmised that Sellers suffered from depression and anxiety over his career, which he often viewed as a failure. Further evidence of his troubled psyche was glimpsed in interviews that asked him about his penchant for disappearing into his characters. His response was that there was no “Peter Sellers,” but rather, a blank slate that adapted to the needs of the role.

The greatest example of the extent to which Sellers could immerse himself into a role was perhaps Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove, Or How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love the Bomb” (1964). The black comedy, about a series of political blunders which lead to World War III, allowed Sellers to play several roles: U.S. President Merkin Muffley, British officer Lionel Mandrake, and the sinister Dr. Strangelove, a wheelchair-bound nuclear scientist whose crippled body seemed hellbent on betraying his Fascist past. Sellers was initially asked to also play Major T.J. “King” Kong, the U.S. Air Force officer who rides the bomb bronco-style as it descends on the Soviet Union, but an injury forced Sellers to abandon the role, which was given to veteran Western performer Slim Pickens. Sellers found both the humor and the horror of the characters in his performances, which received an Oscar nomination, and seemed to indicate that he could move into dramatic roles – his abiding wish. However, he suffered a string of debilitating heart attacks – 13 over the course of a few days – that curtailed his availability. Desperate to return to work, he sought the aid of psychic healers for his condition, which would continue to deteriorate over the next two decades. He also threw himself headlong into film work, which varied, often wildly, in quality.

Sellers longed to play romantic roles, such as his singing matador in “The Bobo” (1967), but audiences responded more to his buffoonish turns, like the accident-prone Indian actor in Edwards’ “The Party” (1968) or the Italian jewel thief who poses as a film director in order to smuggle gold out of Europe in the Neil Simon-penned “After the Fox” (1966). He attempted to play James Bond in the all-star vanity project “Casino Royale” (1967), but abandoned the film after clashing with co-star Orson Welles and, allegedly, realizing that the film was in fact, a comedy and not a straight action piece. The end of the decade, which saw him diving into the counterculture with “I Love You, Alice B. Toklas!” (1968) and “The Magic Christian” (1969), which co-starred his close friend, Beatle Ringo Starr, also marked the conclusion of his lengthy tenure as a movie star for some years.

The first half of the 1970s was a period of deep personal and public failure for Sellers. His marriage to Eklund had ended on an explosive note in 1968, and his 1970 marriage to Australian model Miranda Quarry followed suit in 1974. His film career was in total freefall; pictures like “There’s a Girl in My Soup” (1970), “Ghost in the Noonday Sun” (1973), which reunited him with Spike Milligan, and “The Great McGonagall” (1974), were box office disasters. Sellers’ health also continued its downward spiral due to his reluctance to treat his condition with Western medicine, and a growing dependence on alcohol and drugs. The spell of bad luck broke in 1974 with the fourth “Pink Panther” film, “Return of the Pink Panther,” which reunited him with Blake Edwards once again. The result was a colossal hit for Sellers, and a career revival that lasted for the remainder of his life.

However, Sellers was mentally and physically unprepared for the rush of attention and work that came in the wake of “Return.” His relationship with Edwards had crumbled. By the time they began the rushed sequel to “Return,” 1976’s “The Pink Panther Strikes Again,” Sellers was unable to perform many of his own physical gags, and Edwards would later describe his emotional state at the time as “certifiable.” “Strikes Again,” however, was another hit, with Golden Globe nominations for the film and its star, who began working in earnest on several films. “Murder By Death” (1976) was an all-star parody of detective films, with Sellers playing a short-tempered version of Charlie Chan, while “The Prisoner of Zenda” (1978) was a lukewarm adaptation of the familiar Anthony Hope novel about a commoner (Sellers) recruited to impersonate his look-alike, the king (also Sellers) of a tiny European country. Sellers, however, had his attention fixed elsewhere.

For several years, he had worked in earnest to secure the film rights to Jerzy Kosinski’s novel Being There, about a simple gardener who becomes the confidante to the rich and powerful. The project went before cameras in 1979, with Sellers giving one of his richest performances in a role that seemed tailor-made for him – a man with no discernible personality, yet the ability to fascinate and inspire so many around him. The film was a critical and audience success, and won Sellers a Golden Globe and an Oscar nomination. The validation and acclaim, however, would be short lived.

Sellers had suffered another punishing heart attack in 1977, which required him to be fitted for a pacemaker. Though he had resisted having heart surgery for years, he finally relented, and in 1980, was slated to undergo an operation in Los Angeles. Just days before the surgery, Sellers suffered a massive heart attack which sent him into a coma. He died two days later on July 24, 1980, just one day before a scheduled reunion dinner with his Goon Show partners, Spike Milligan and Harry Secombe. He was survived by his fourth wife, actress Lynne Frederick, and his three children. At his funeral, the Glenn Miller song “In the Mood” was played for mourners. It was a fitting touch for a man who reveled in the darker side of humor; the song was reportedly one that the 54-year-old Sellers had long hated.

While the Hollywood community mourned his premature loss, the anarchy that swirled around Sellers continued to broil after his death. In 1979, Blake Edwards shocked many by releasing “Revenge of the Pink Panther,” which featured Sellers in outtakes from several of the previous films. It was roundly panned, but did not dissuade him from cobbling together another Clouseau movie, “Trail of the Pink Panther” (1982), from outtakes. Sellers’ final film, a dismal comedy called “The Fiendish Plot of Fu Manchu,” which he also co-directed, was released in 1980. Edwards would continue to labor over the Pink Panther franchise for two more films – “Curse of the Pink Panther” (1983), with Ted Wass as a Clouseau-esque policeman, and “Son of the Pink Panther” (1993), with Roberto Begnini as Clouseau’s illegitimate offspring – both of which were disastrous failures. Sellers’ estate was also the source of considerable dismay for his family members. .