Jean Simmons obituary in “The Guardian” in 2010.

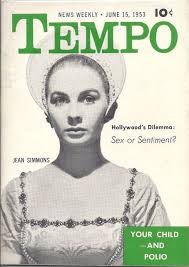

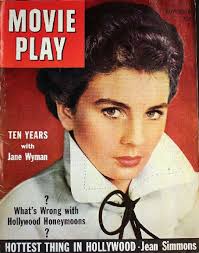

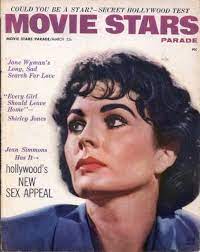

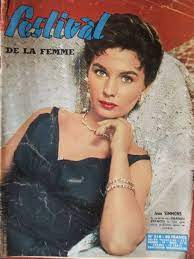

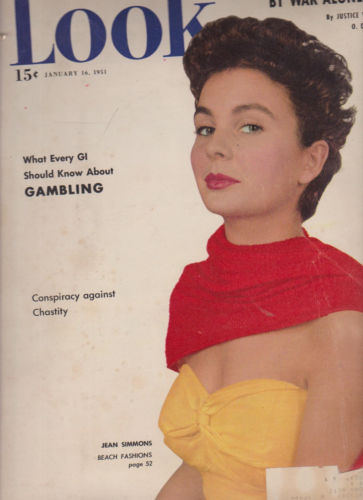

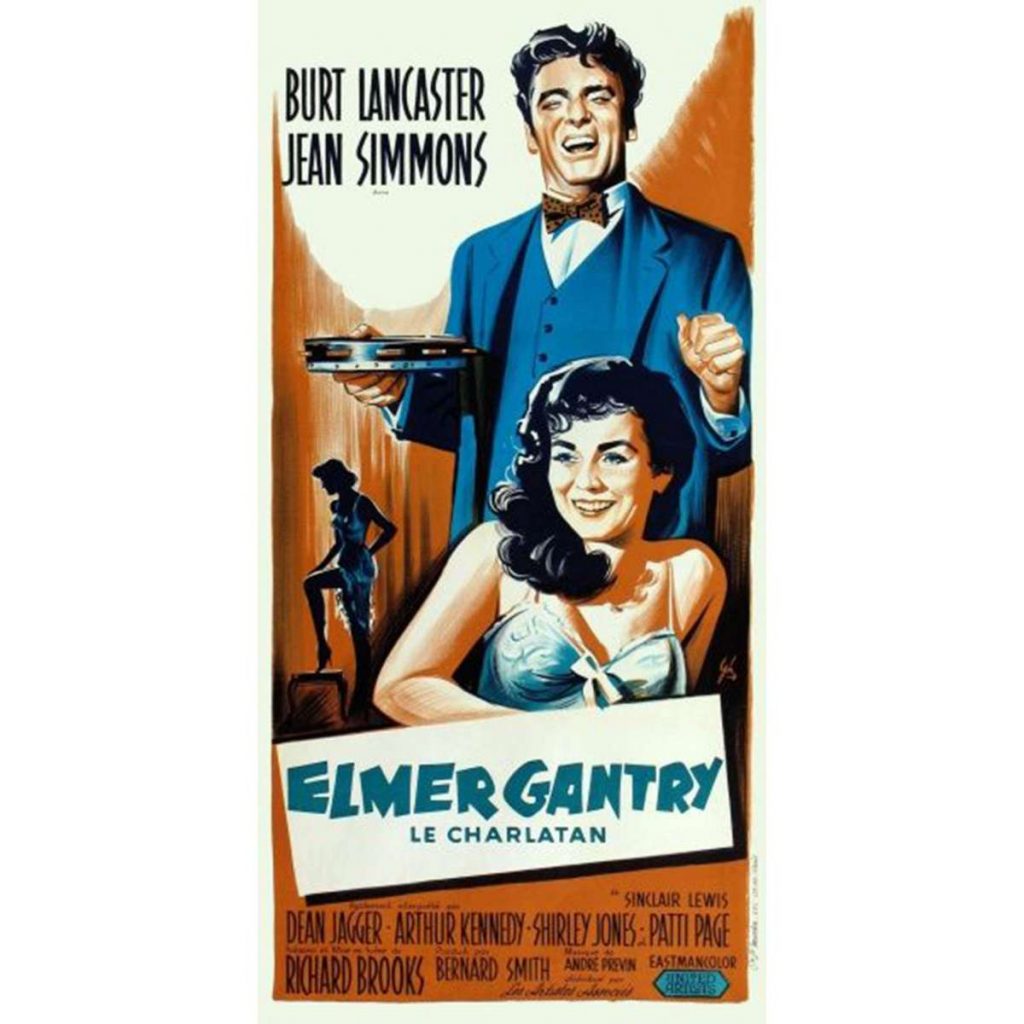

Jean Simmons has always been taken for granted, As a child player in Britain she was expected to be one of the best child players and she was: she was expected to become a big international name and she did. In Hollywood for over 20 years she was given good roles because she was reliable and she played them, or most them, beautifully. But she was never a cult figure, one of those who adorn magazine covers, or someone the fan magazines write about all the time. It was not or is not that she simply did or does her job – she is much better than that, she is not a competent actress, she is a very good one – by Hollywood standards a great one, if you take the Hollywood standard to be those ladies who have won Oscars. She was not even nominated for Best Actress Oscar till 1969. She not even nominated for “Elmer Gantry” (and that year Elizabeth Taylor won). Maybe it does not help to have been so good so young” – David Shipman – “The Great Movie Stars – 2 The International Years” (1972)

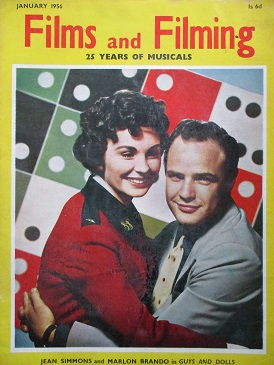

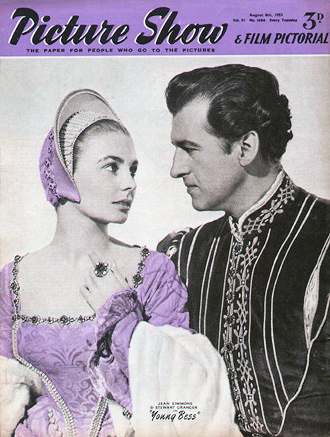

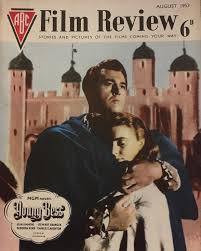

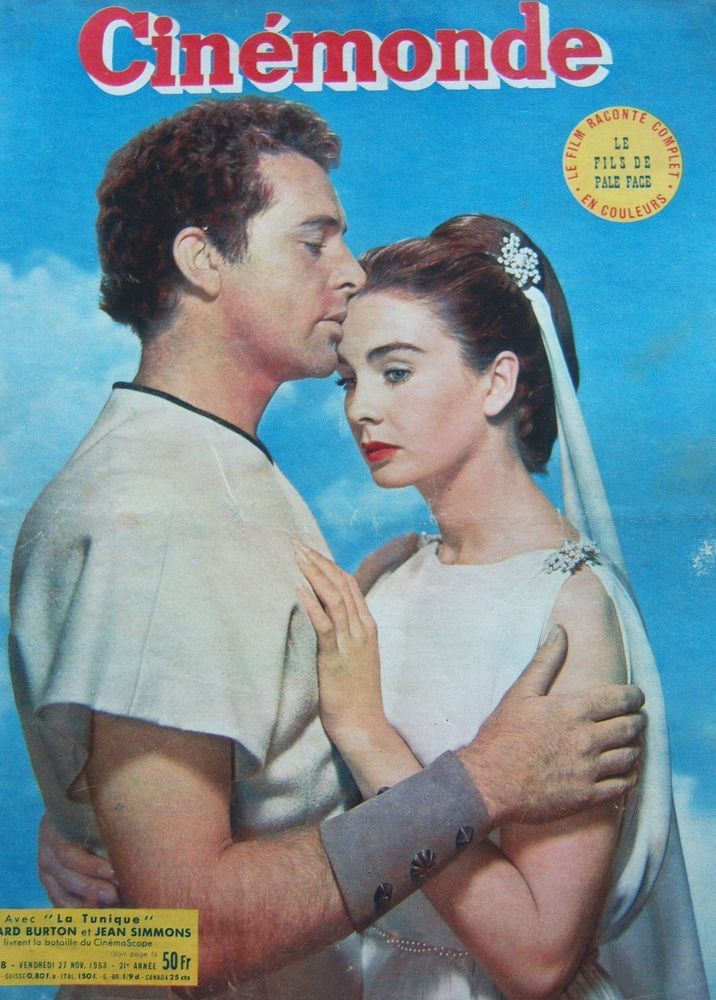

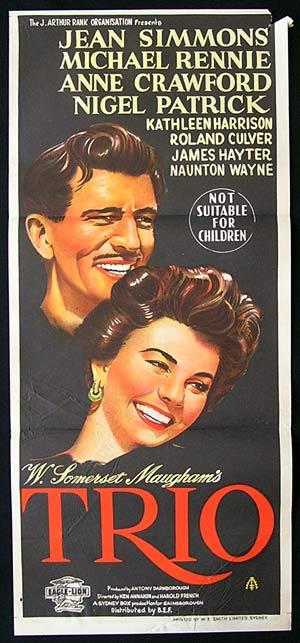

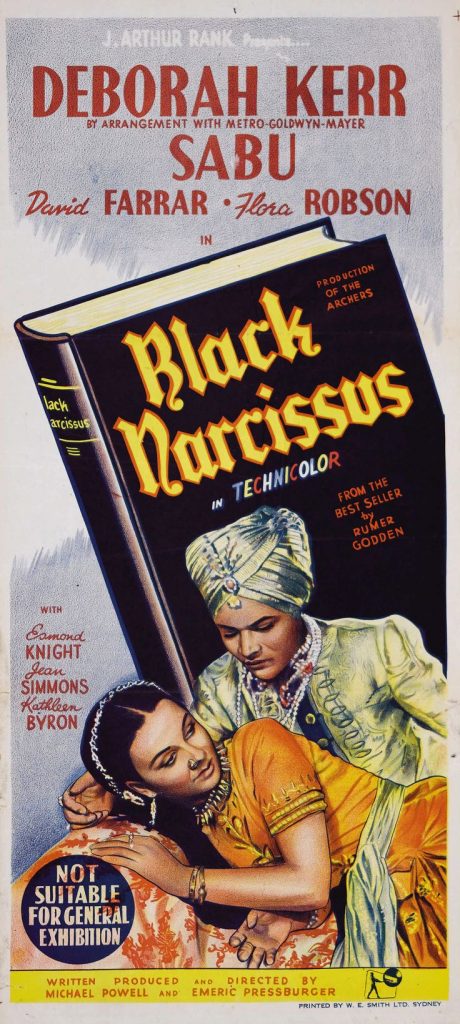

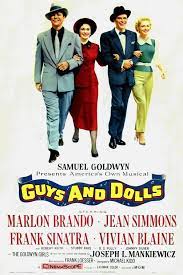

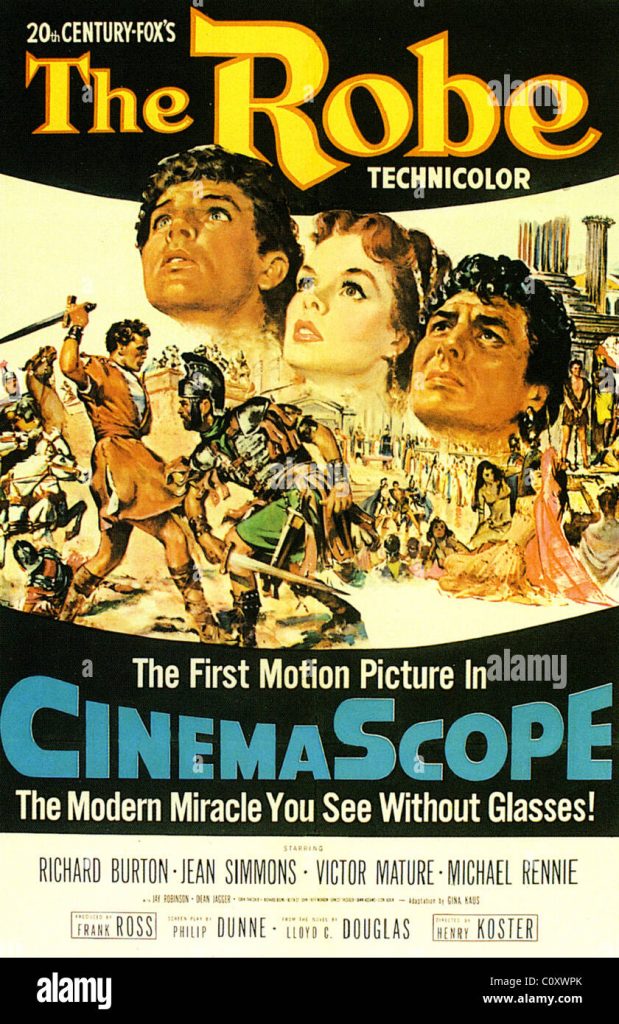

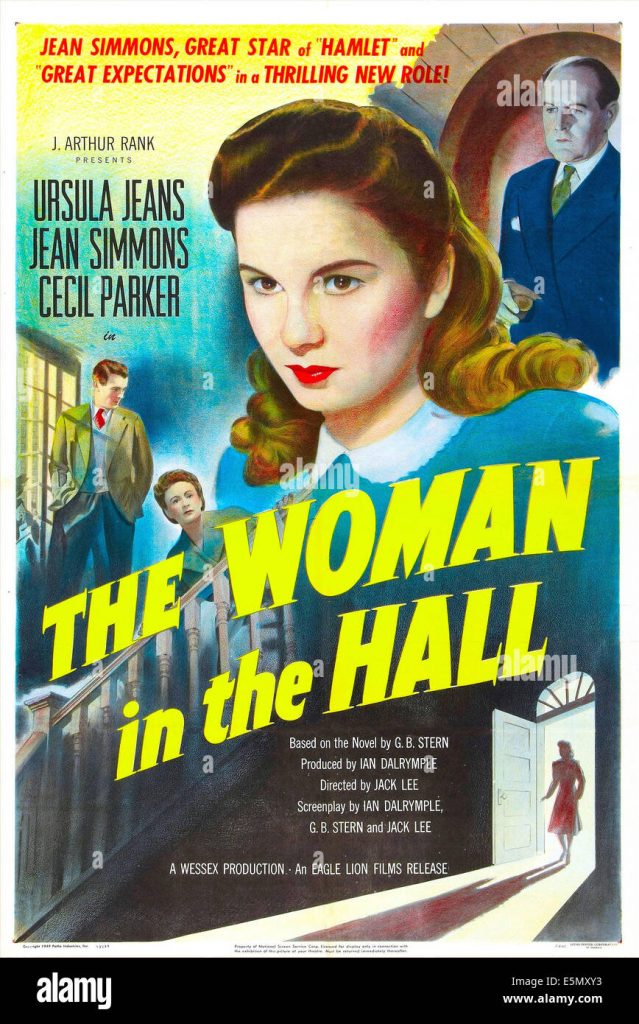

Jean Simmons was a major star actress in British movies of the late 1940’s with important roles in such films as “Great Expectations” in 1946, “Hungry Hill”, “Black Narcissus” and The Clouded Yellow”. She went to Hollywood in 1950 and was a major international star for over ten years starring in “The Robe” opposite Richard Burton in 1953, “Young Bess” with Spencer Tracy”, “Guys and Dolls” with Marlon Brando and Frank Sinatra and in 1960, “Elmer Gantry” opposite Burt Lancaster. She continued acting in film, television and on the stage up to her death at the age of 80 in 2010.

David Thompson’s “Guardian” obituary:

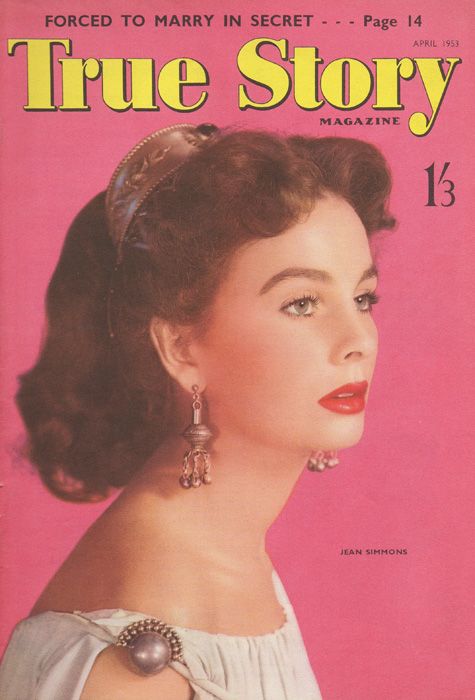

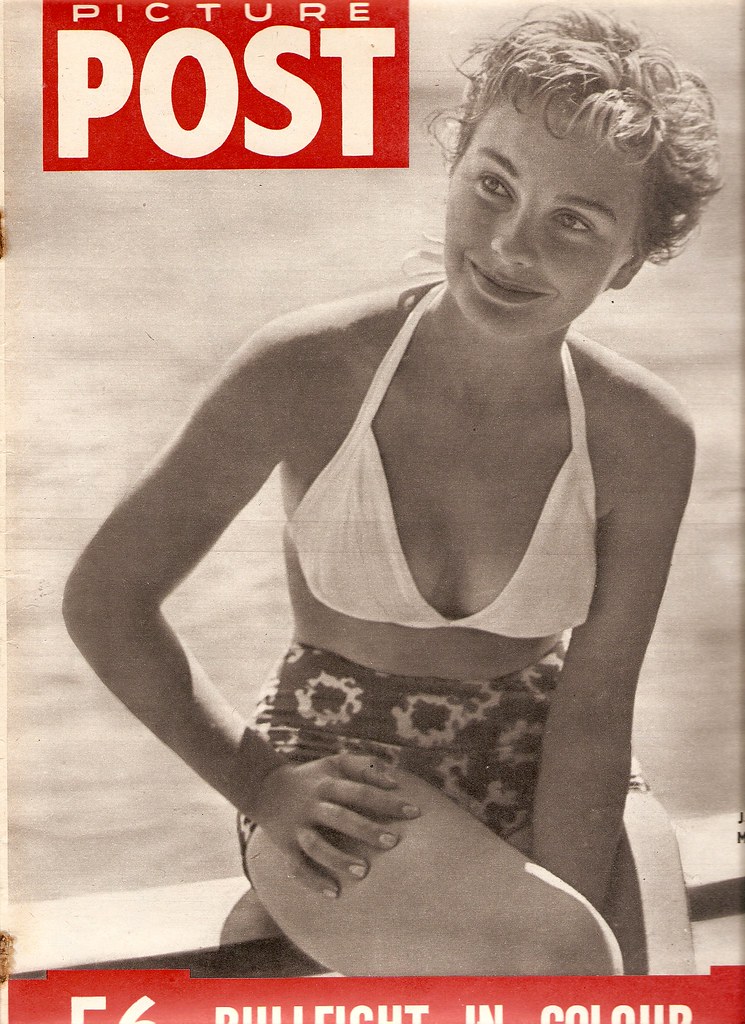

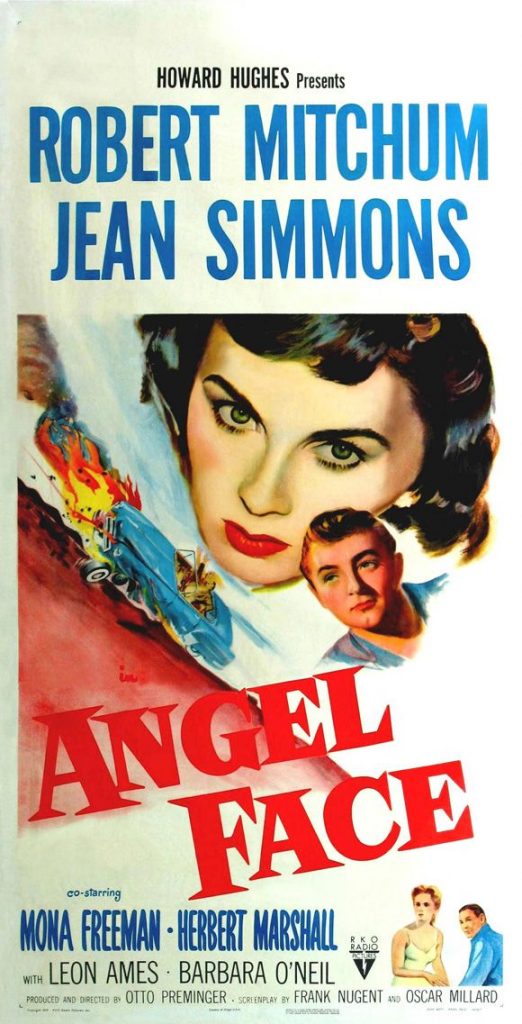

Jean Simmons, who has died aged 80, had a bounteous moment, early in her career, when she seemed the likely casting for every exotic or magical female role. It passed, as she got out of her teens, but then for the best part of 15 years, in Britain and America, she was a valued actress whose generally proper, if not patrician, manner had an intriguing way of conflicting with her large, saucy eyes and a mouth that began to turn up at the corners as she imagined mischief – or more than her movies had in their scripts. Even in the age of Vivien Leigh andElizabeth Taylor, she was an authentic beauty. And there were always hints that the lady might be very sexy. But nothing worked out smoothly, and it is somehow typical of Simmons that her most astonishing work – in Angel Face (1952) – is not very well known.

At first, she was a schoolgirl given her dream. Born in north London, she grew up in the suburb of Cricklewood, and was swept from dancing classes to the studio to be Margaret Lockwood’s younger sister in Give Us the Moon (1944). Several other films followed, with modest roles: Mr Emmanuel; Kiss the Bride Goodbye; Meet Sexton Blake; a singer in The Way to the Stars; and a slave girl for Leigh in Caesar and Cleopatra.

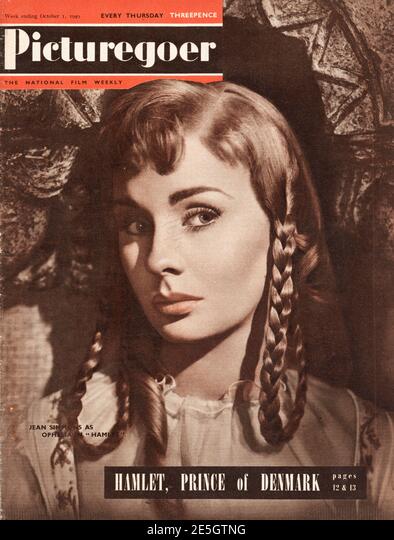

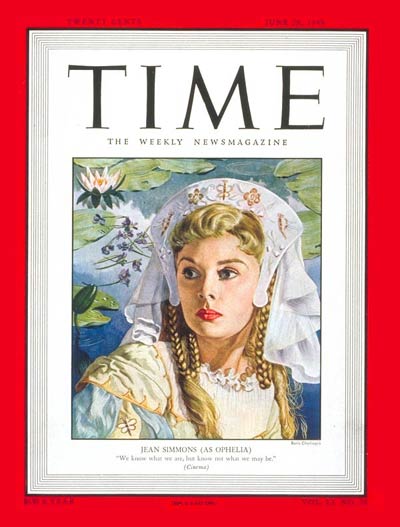

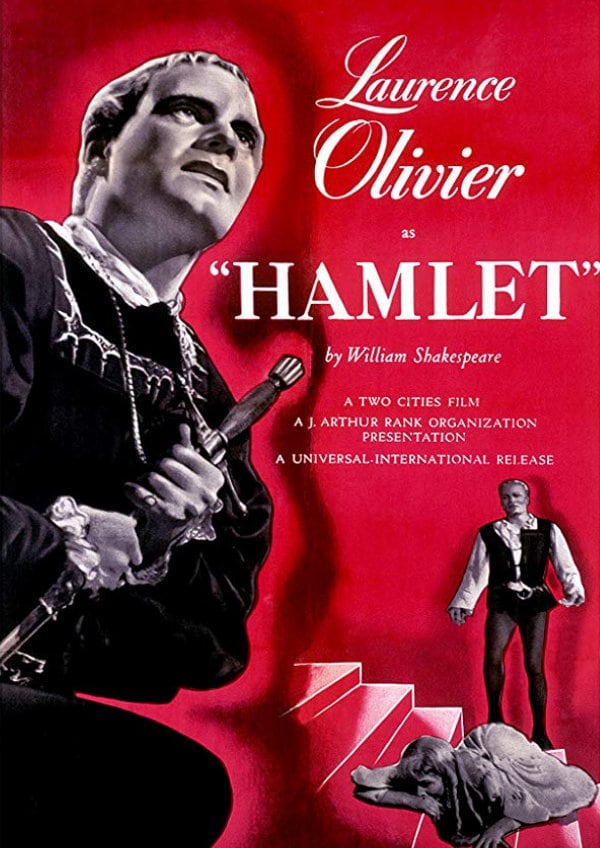

But then David Lean cast her as Estella in Great Expectations (1946); Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger chose her to be the temple dancer with a jewel in her nose for Black Narcissus (1947); and Laurence Olivier borrowed her away from her J Arthur Rank contract so that she could be a blonde Ophelia in his Hamlet (1948). It was noted at the time that an anxious Leigh, Olivier’s wife, chose to be on set whenever Simmons was working – just in case.

Hamlet won the Oscar for best picture, and Simmons was nominated for best supporting actress; in fact, she lost to Claire Trevor in Key Largo. However, she was by then an expert at the Oscars, for she attended the previous year and four times was on stage to accept awards on behalf of Great Expectations and Black Narcissus. Cecil B DeMille, in the audience, was so impressed that he offered her the female lead in his upcoming Samson and Delilah (the Hedy Lamarr role). She had to decline – for Hamlet’s sake – but no young actress was being talked about more.

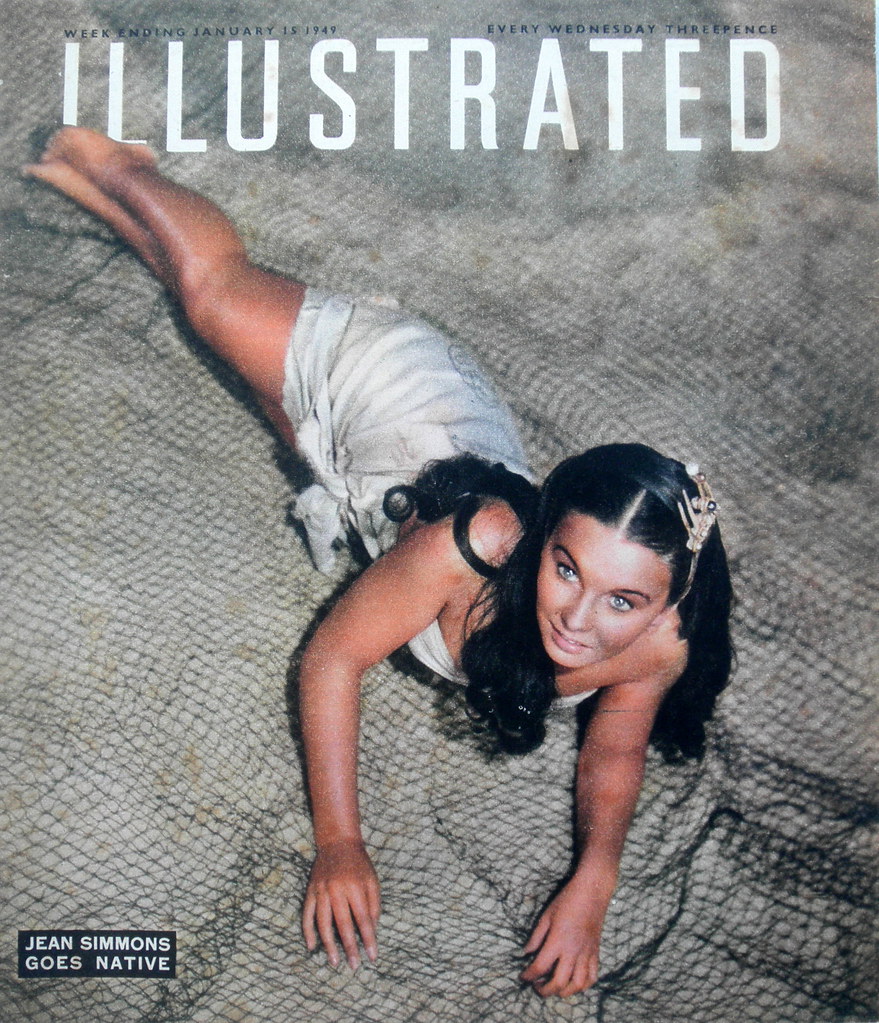

For a while she remained in Britain. She was also in the Daphne du Maurier tale of an Irish feud, Hungry Hill (1947); and she was suitably preyed upon by Derrick DeMarney in Uncle Silas, adapted from the Sheridan Le Fanu novel. Then, in 1949, with Donald Houston, she was one of two young people shipwrecked on a desert island in The Blue Lagoon. Showing a good deal of flesh for its day (Brooke Shields took her role in the 1980 remake), this was reckoned as a rather daring film – and it was almost certainly viewed, and re-viewed, by Howard Hughes. Then, in the same year, she played the adopted daughter of Stewart Granger in Adam and Evelyne. In fact, the handsome Granger was 16 years her senior, and married once, having divorced Elspeth March in 1948. But the couple fell deeply in love, married and would soon set out together for Hollywood as a kind of middleweight Olivier and Leigh.

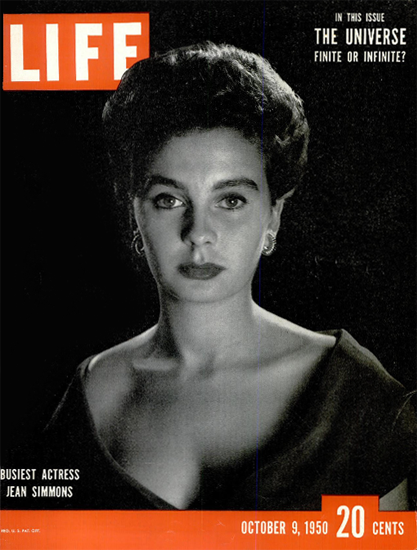

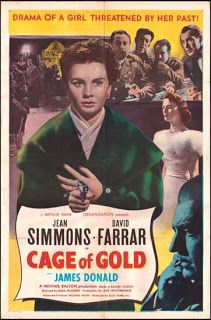

But that was not before three 1950 films – So Long at the Fair, a period thriller in which she was romantically paired with Dirk Bogarde; Cage of Gold; and The Clouded Yellow, in which she established a fascinating mood with Trevor Howard. And so, aged only 21, she went to Hollywood. But whereas Granger was under contract to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (and would play Allan Quartermain, the Prisoner of Zenda and Scaramouche), she was the oblivious dream child of Hughes at RKO, which had bought her contract from Rank. The strange tycoon was obsessed with her personally, and he laid siege to her romantically and professionally so that she did not work for over a year. Only one thing emerged from the stand-off, Angel Face, in which she is a spoiled child and lethal temptress who seduces nearly everyone she meets (most notably Robert Mitchum). The brilliant picture was directed by Otto Preminger and photographed by the great veteran Harry Stradling. Thus it contains – and she sustains – some of the most luminous close-ups ever given to a femme fatale. How far she understood the picture is unclear. One can only say that it is a rare tribute to unrequited love.

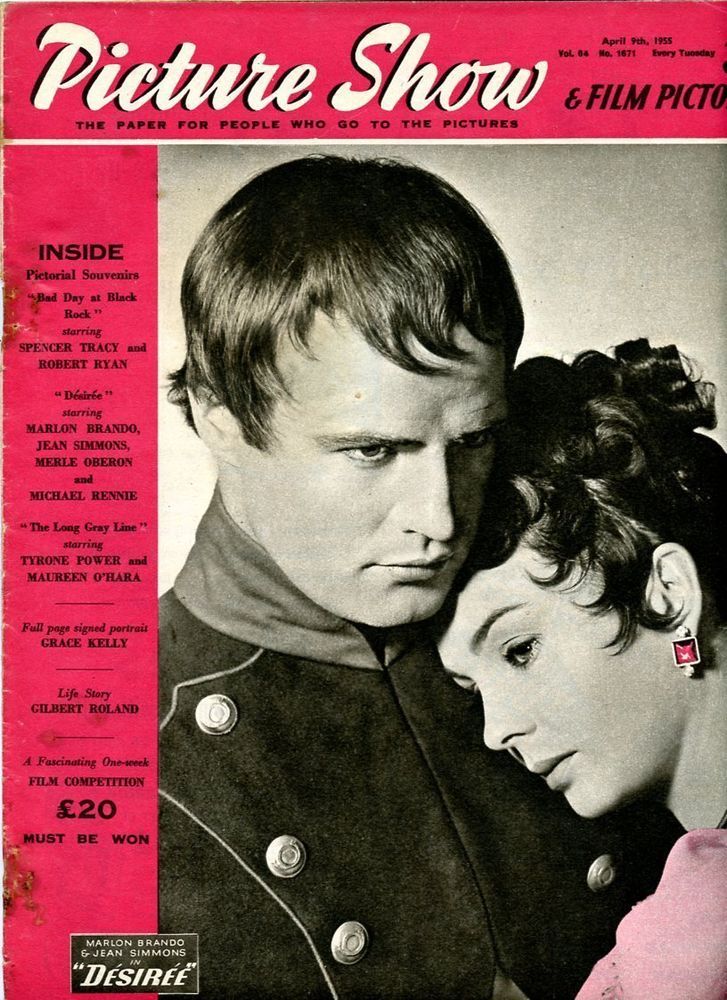

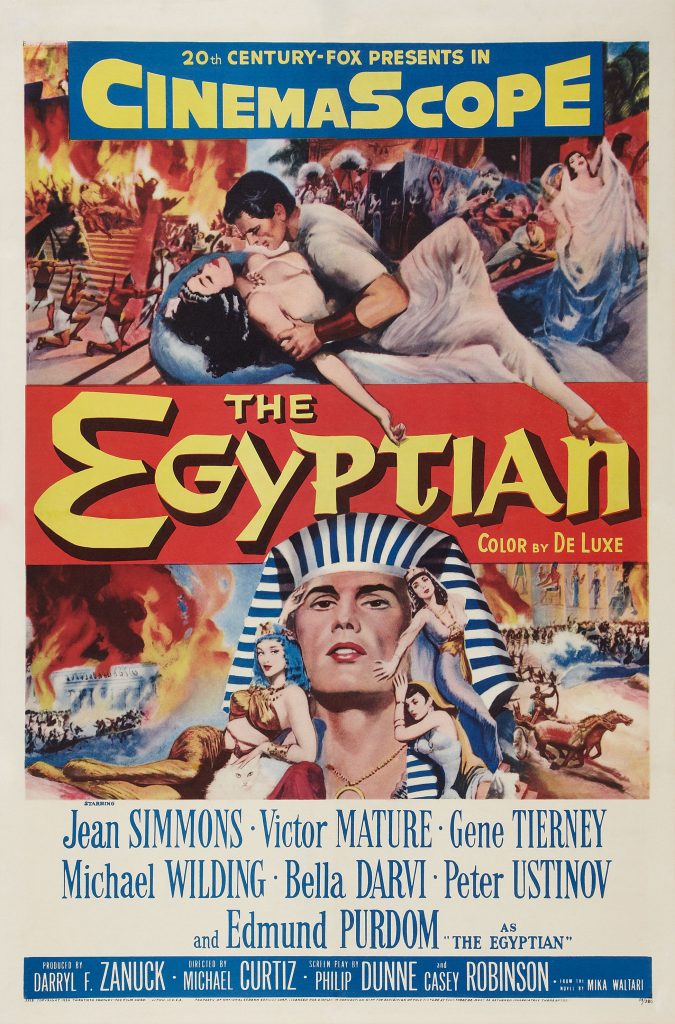

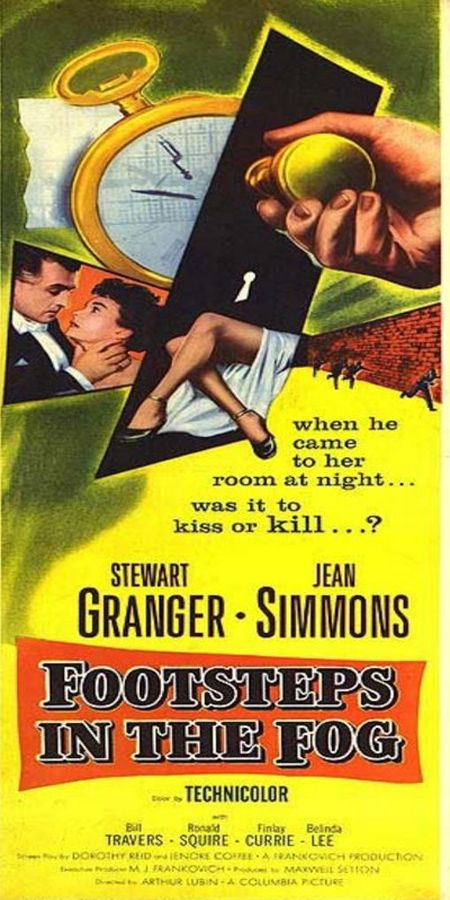

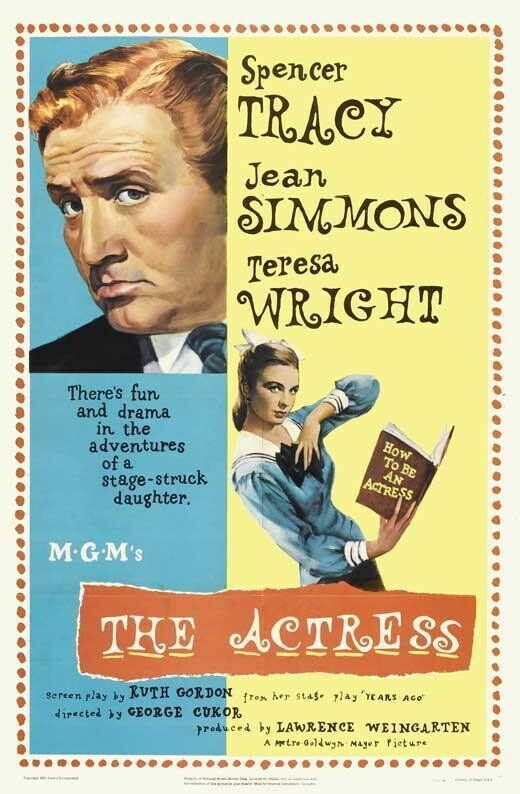

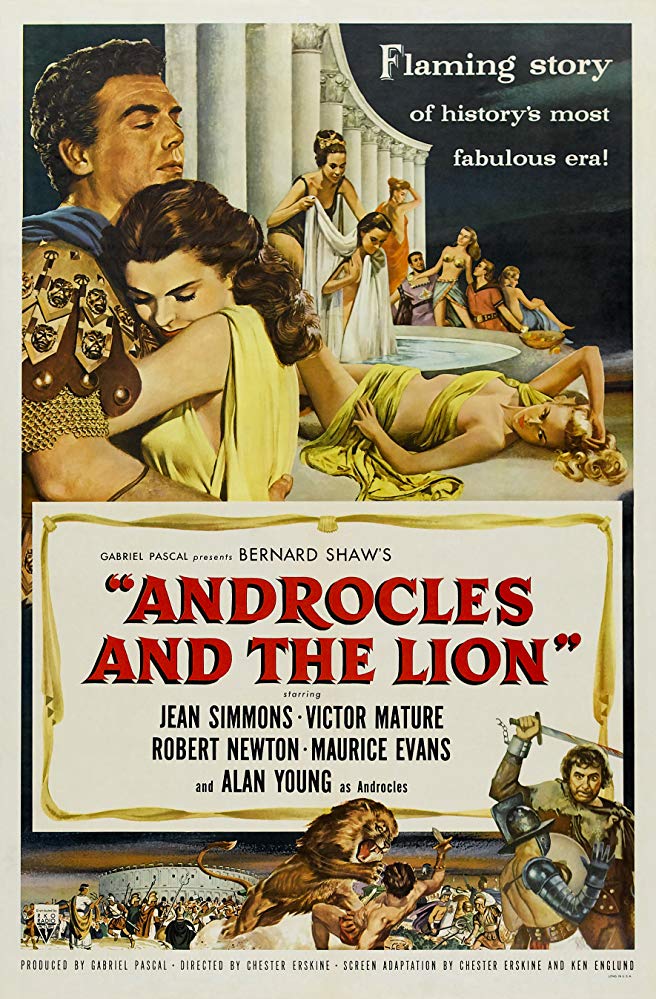

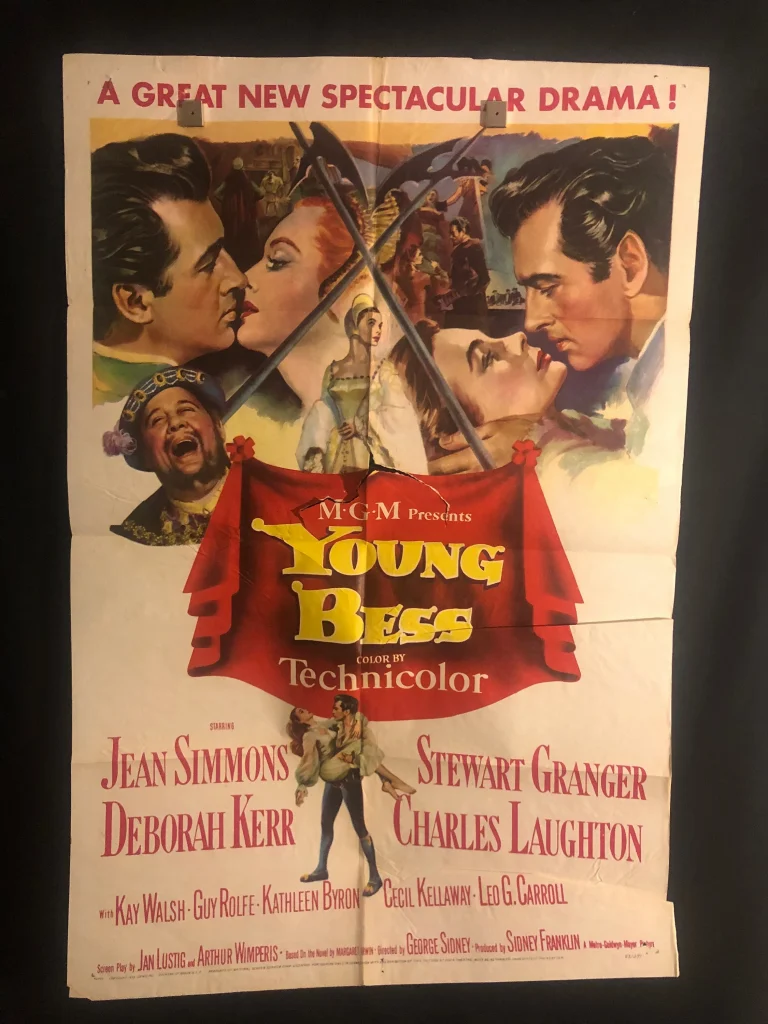

Hughes yielded in the courts in 1952, and Simmons was able to begin a run of costume films, some of them important productions (such as The Robe), but many of them giving her too little to do: in Androcles and the Lion; as Elizabeth I in Young Bess (with Granger, Deborah Kerr and Charles Laughton); very good, though too pretty, as the young Ruth Gordon in George Cukor’s The Actress – she worked especially well with Spencer Tracy. But then the films grew more routine: Affair With a Stranger (with Victor Mature); with Richard Burton and CinemaScope in The Robe – there may have been a fling with Burton; She Couldn’t Say No – she should have; the dreary The Egyptian; A Bullet Is Waiting, in which she was expected to take Rory Calhoun as co-star; Désirée – ruined by the languid mockery of co-star Marlon Brando; and Footsteps in the Fog (with Granger).

She took a risk, singing If I Were a Bell and The Eyes of a Woman in Love, to be Sister Sarah in the movie of Guys and Dolls (1955). The producer, Sam Goldwyn, had wanted Grace Kelly for the part. But director Joseph L Mankiewicz was more than happy with Simmons: “An enormously underrated girl. In terms of talent, Jean Simmons is so many heads and shoulders above most of her contemporaries, one wonders why she didn’t become the great star she could have been.” No one argued, though many observers noted that Mankiewicz was also deeply in love with his actress. Still, it is worth speculating, and noting that nothing sounds wrong or unpromising about this schedule – Jean Simmons in Roman Holiday, in Vertigo, in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof?

• Jean Merilyn Simmons, actor, born 31 January 1929; died 22 January 2010

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

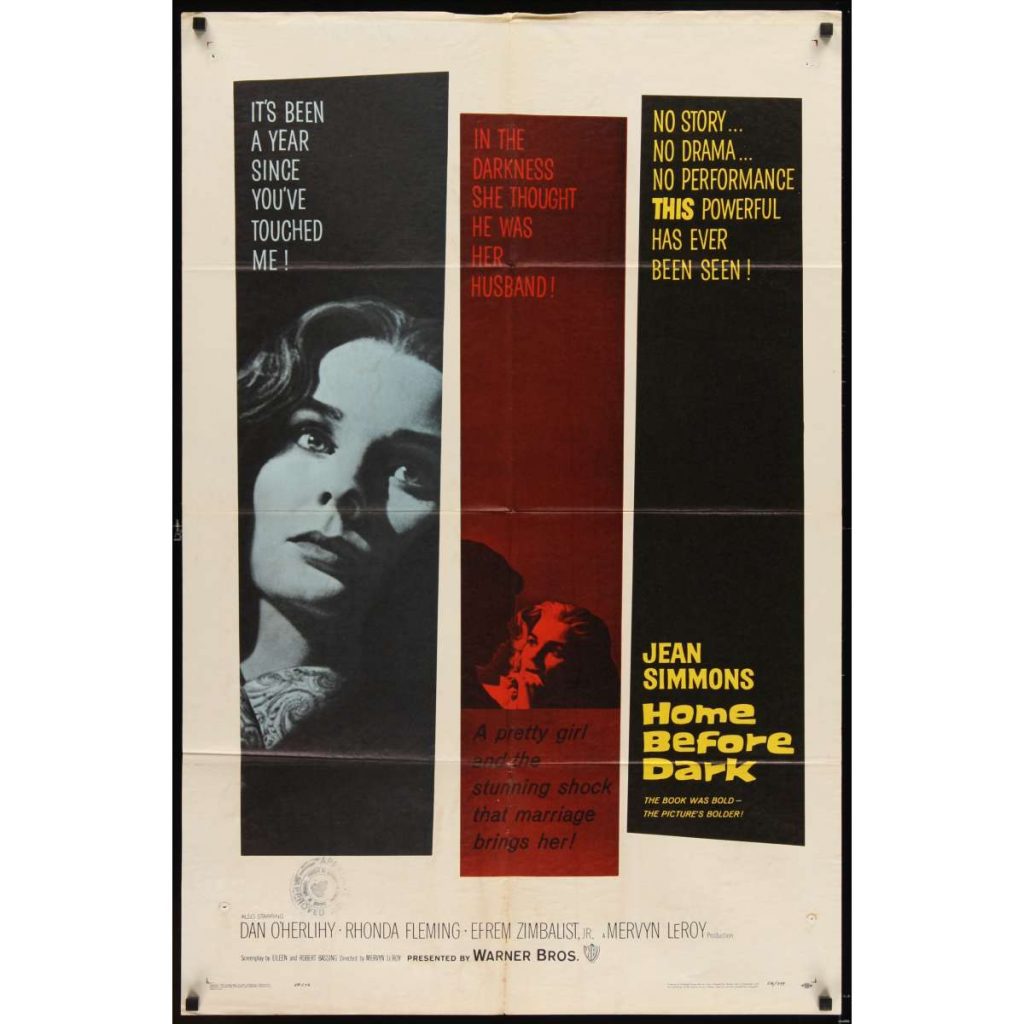

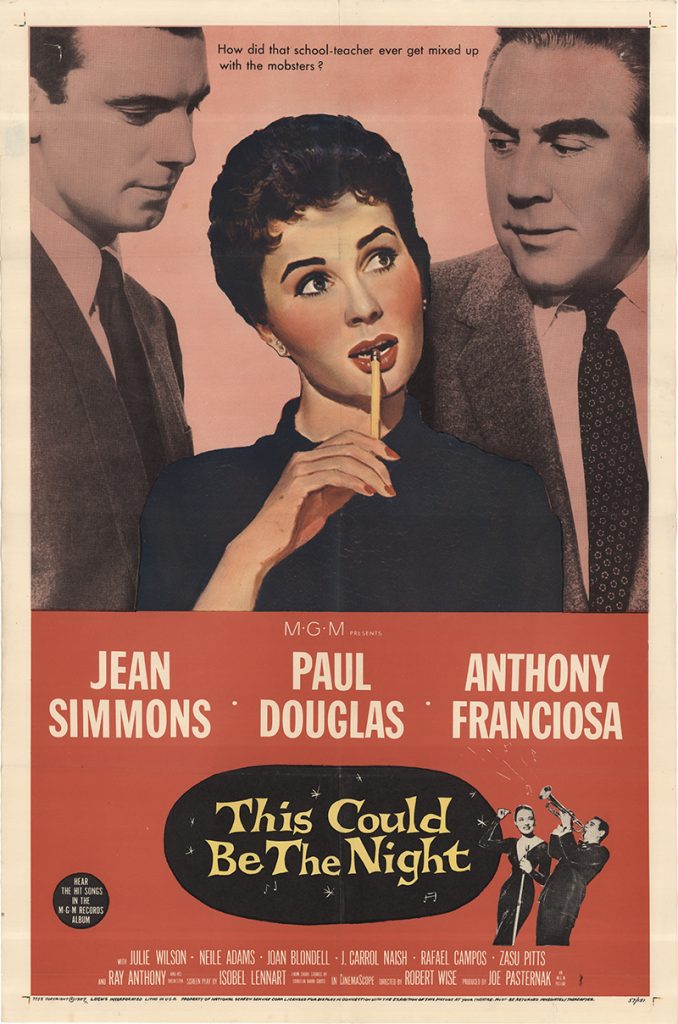

When one considers that she was barely past 25 in 1955, it is all the stranger that her films slipped so far in quality: Hilda Crane; as secretary to gangster Paul Douglas in This Could Be the Night; with Paul Newman in Until They Sail; with Gregory Peck and Charlton Heston in the big western, The Big Country; This Earth is Mine. One notable exception to this trend was Home Before Dark (1958), where Simmons was outstanding as a woman who has had a nervous breakdown.

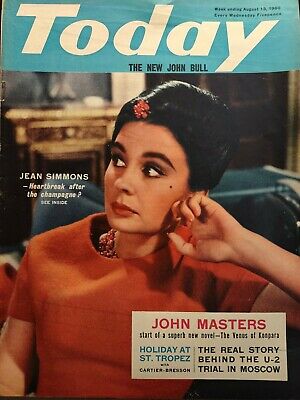

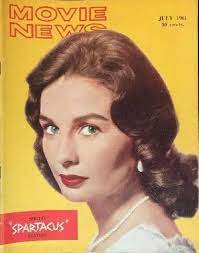

By then, her marriage to Granger had come apart. But in 1960, she married again, the writer-director Richard Brooks, and he immediately raised her horizons by casting her as the evangelist opposite Burt Lancaster in Elmer Gantry. Lancaster and Shirley Jones won Oscars in that film, but Simmons was not even nominated. Thereafter, she sportingly played the female lead in Spartacus, and had some overlong, giggle-making love scenes with its star, Kirk Douglas – “Put me down, Spartacus, I’m having a baby!”

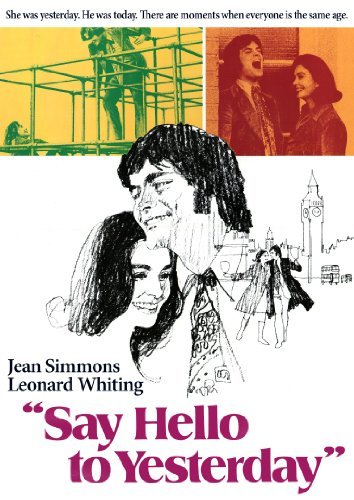

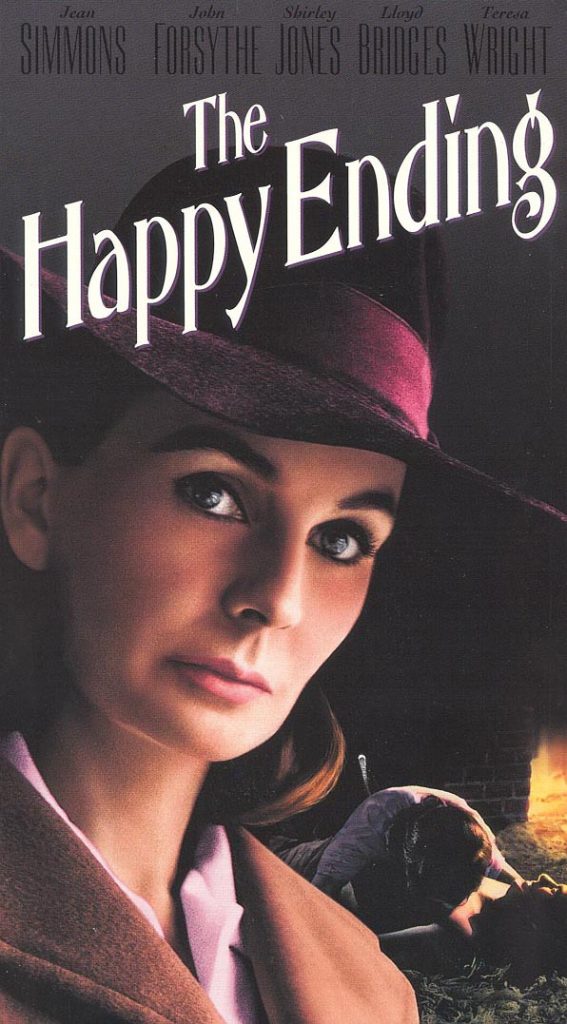

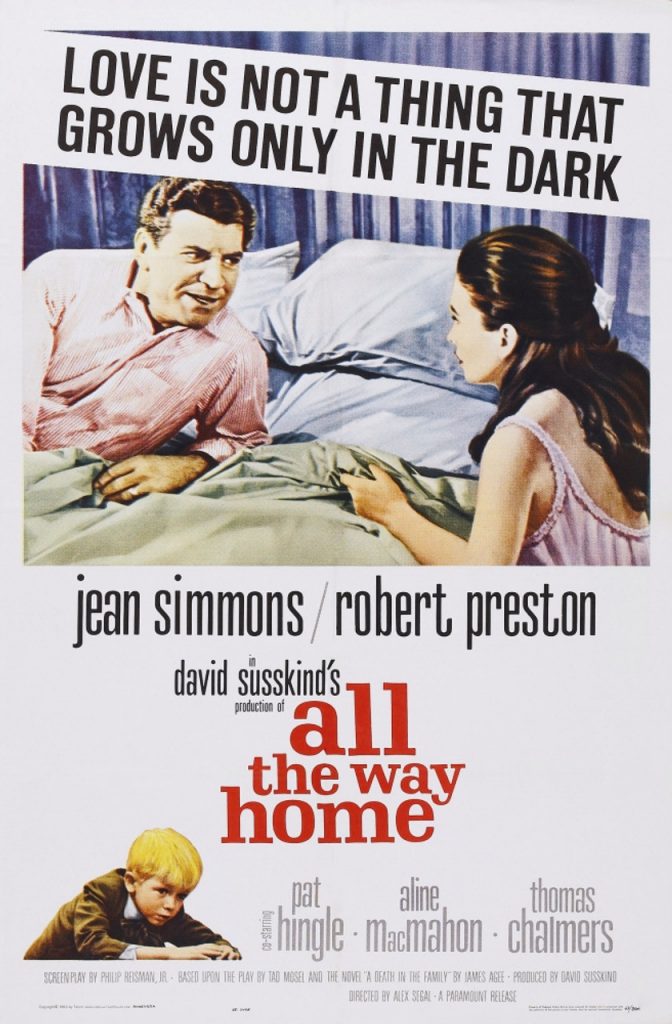

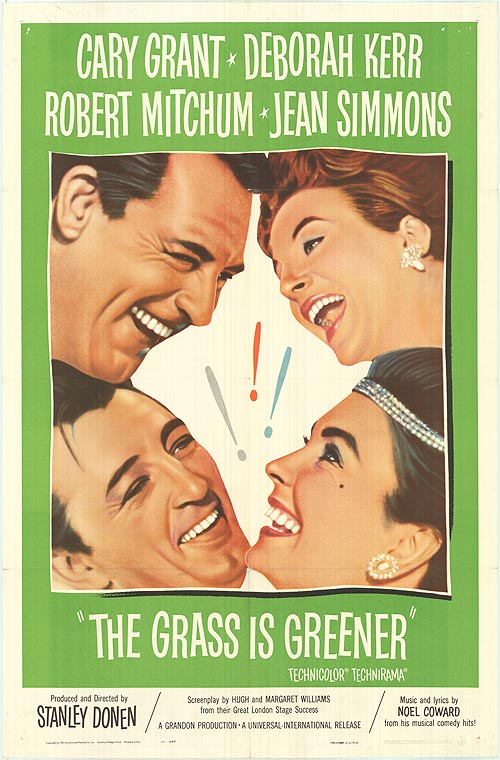

That would prove to be her last big picture, for the slide was now evident: The Grass is Greener (1960, a rather middle-aged comedy); All the Way Home, adapted from James Agee’s novel, in which she was very good, but which went unnoticed; Life at the Top (done back in Britain); Mister Budd- wing; Divorce American Style and Rough Night in Jericho. Then Brooks did all he could to revive her fortunes in The Happy Ending (1969), about a miserable wife whose dreams of marriage, based on the movie Father of the Bride, have turned to disillusion. She got an Oscar nomination for it (she lost to Maggie Smith in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie), but rather more out of respect than conviction. In truth, she always seemed too strong-willed and amused for weepy material. Indeed, she might have done Jean Brodie.

More or less, in the early 1970s, she seemed to retire. The marriage to Brooks came to an end in 1977, and there were stories that she was drinking too much. In the early 1980s she checked herself in to the Betty Ford clinic and spoke publicly about her addiction.

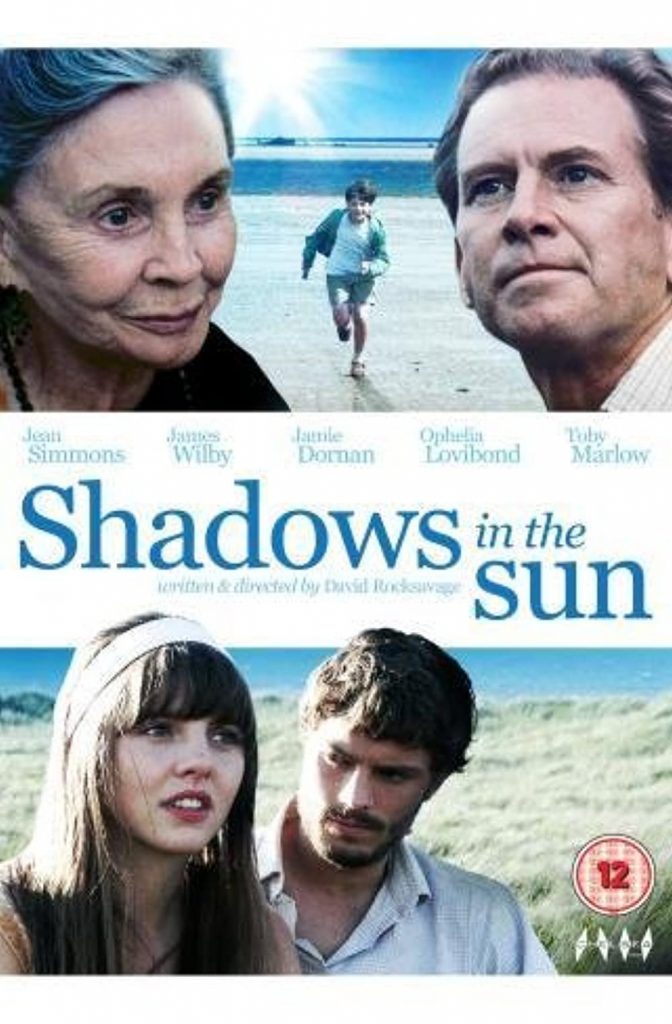

Then she started to work in television, and sometimes it was only the end credits that told one that that had been Jean Simmons. She was in The Thorn Birds (1983); she did a TV version of Great Expectations where she was Miss Havisham (1989); was an admiral called in for an investigation in Star Trek: The Next Generation (1991); and was in How to Make an American Quilt (1995). She went into semi-retirement and was often too shy to accept invitations to film festivals. But around 75, she changed: she did a wonderful voice performance in Hayao Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), and she was deeply touching as a dying poet in Shadows in the Sun (2009). She attended the Telluride Film Festival, Colorado, in 2008 and she was interviewed at a Lean centenary celebration in Los Angeles where she was still as pretty, seductive and mischievous as she had been as Estella in Great Expectations.

The recollection of those early years brings out the paradox of her career, for if she had made only one film – Angel Face – she might now be spoken of with the awe given to Louise Brooks. She is survived by her daughters Tracy, from her marriage to Granger, and Kate, from her marriage to Brooks.