Terry Kilburn, actor, director, artistic director, recently talked at length with this Lavender writer about his early life, describing in cinematic detail how the only child of working class parents, Tom and Alice Kilburn, came to star in Hollywood at MGM delivering such coveted film lines as, “God bless us, every one,” and “Goodbye, Mr. Chips.” Born November 25, 1926 in London, he appeared in over 25 films, including, along with those mentioned here in detail, National Velvet (1944, with Liz Taylor), and Only the Valiant (1951, with Gregory Peck). His extensive stage work will appear in part two of this interview.

My father was a bus conductor, taking tickets on those big double-deck buses. He’d run up and down the stairs making jokes and entertaining– sometimes he’d have the whole bus laughing. I think he would liked to have gone on the stage, he was a natural entertainer.

My mother was a housewife, and in the summertime used to run a boarding house at Clackton-on-Sea, where working-class people went for their week’s holiday. She was in the kitchen and making the beds and setting tables from morning to night. My father stayed up in London and would come down on the weekends in a little baby Austin car about the size of this dining table. I had a lot of time to myself.

There was an amusement pier where a man called Clown Bertram ran a little theater. Children would come up on the stage and do a little something, then the one who got the most applause would get a prize. I was much too shy to do that although I loved watching the show.

One time, my mother had some friends who left their two children for her to take care of. The little girl sang a song and did a dance on Clown Bertram’s stage, and she won the first prize. The next day, I got over my shyness enough to go up and I sang a song. I was a big flop, but it broke the ice. I was about seven.

My parents used to take me with them to the movies. Movies then were an incredible source of entertainment for poor and working class people. For a sixpence, or a shilling, you could see the main feature and a companion feature, a newsreel, a short subject, a cartoon. Most theaters still had a couple of stage acts from vaudeville, and on top of all that, up from the orchestra pit would come an organ, all lit up, and you’d have a community sing.

I started impersonating these people that I saw on the screen, Jean Harlow, Greta Garbo, Mae West, Zazu Pitts, Charles Laughton, and Ronald Colman. Sometimes, I’d do impersonations for relatives spontaneously, but usually, my shyness overcame me and I couldn’t. But when this girl won the first prize, that got my competitive spirit up. The second time, I went up and did some impersonations and won hands down. It was like an electric light going on over my head. Many actors will tell you of this experience, when they first realize that they have an ability to bring out that response from an audience. From then on, I was on that stage every day.

My father was very interested, and when we got back to London he submitted me for amateur night competitions. I worked up a little act, doing my impersonations and I came on singing, “OK Toots,” an Eddie Cantor song. That’s kind of interesting because later on Eddie Cantor played an important part in my life, and I did a little tap dance that I taught myself, having seen Fred Astaire.

The first prize was something like ten pounds, while my father–this was in the Depression–was making two pounds a week. We started going around the circuit, to all these huge old variety houses that seated two thousand people. My big ending was a scene from David Copperfield, where Mr. Murdstone, the wicked stepfather, beats David. I did both parts, and ended sobbing and having hysterics on the floor as David, then standing up with a big smile and bowing.

Through what we today call “networking,” one thing led to another.

Into our lives came Freddie Newton. He was a Dickensian character, a little Cockney who wore checked suits and sharp hats. He had a candy store and was a bookmaker. He helped polish up my act and took me up to the West End of London to meet an actor, Hugh Wakefield. I did my act and Wakefield commented, “I don’t quite know what I just saw, but whatever it is I think he should meet my agent.’

This turned out to be a woman who went only by “Connie,” Ralph Richardson’s agent, who told his parents, “You’ve got to get him to Hollywood.” She then introduced them to a visiting Hollywood lawyer, Roger Marchetti.

Marchetti said, “If you come to Hollywood, you can count on me. I will do everything I can to see that you get auditioned.” Well, when I heard that! Can you think of a thing in your own childhood, the thing that just meant more to you than anything and obsessed your mind? I used to sit up in bed with a globe and spin it and make it stop on the United States.

I think none of this would have happened if it hadn’t been this particular time during the Depression. People had so little to lose. There was a sense of camaraderie and an atmosphere of, “Well, let’s try it!”

There was a great resistance by the U.S. Consulate in London to giving the whole family visas. In the end, after much finagling, Tom stayed behind while Alice and Terry traveled to the United States.

My mother was an amazing combination of guts and timidity. She would take chances that other women of her generation and education would never have dreamed of doing, but she was frightened to death of dogs and the ocean. She’d never been out of London, let alone England, so she would only go on the Queen Mary. We booked the cheapest third-class passage.

Finally, we arrived in Los Angeles. Now this is in April-May of 1937. In those days, the station in downtown Los Angeles was in Chinatown and it was just awful, an old shack that was falling apart. All of our dreams of Hollywood, and out of this glamorous vision we were seeing this terrible slum. And there, in bright, blooming sunshine, was Mr. Marchetti with a huge bunch of red roses, standing next to this immense Packard convertible and chauffeur. It was a surreal picture.

They had expected to stay with Marchetti and his family but were quickly disabused of that idea. He was very much a bachelor, as well as a handsomely paid celebrity divorce lawyer, e.g., (Myrtle) Hardy vs. (Oliver) Hardy.

He didn’t want some English lady and her little boy in his house, so we ended up in a bungalow court, with Murphy beds that pulled out of the wall. We started on the rounds, seeing producers and so forth, and Mr. Marchetti was good to his word. He certainly did his best, but the problem was me. The excitement of performing on stage, or for somebody in his dressing room, seemed to stimulate me and make me a good performer. Now, to have to go into these big offices with people sitting in big swivel chairs smoking cigars–it was too much for a little boy to cope with. And my personality, everything that had made people say “Yes! He’s got something!” just disappeared.

Even more so when they made screen tests. If Marilyn Monroe hadn’t ever gotten in front of a camera, she would have been working in a beauty parlor. She came to life in front of the camera. It was just the opposite for me. The tests were usually shot in the corner of a sound stage where no movie was being filmed at the time, huge, ghostly sound stages about the size of an airplane hangar. It was overwhelming.

A year went by, and the money had run out. Mr. Marchetti said we could move into an apartment over his garage. My mother agreed. She didn’t know what else to do. So we moved, not into his Florentine mansion, but into the garage apartment. He had two Doberman pinscher dogs. My mother was terrified of them, and the apartment was infested with mice.

The whole venture was coming to a bad end. My mother finally told me, “We have to go back, we can’t just stay here forever.” At that very time, my mother got a letter from my father: “I’m getting a ship and I’m coming to Canada, and I’m going to come through the border because I know people do it all the time. I’m on my way! By the time you get this, I be on the Atlantic.”

And then, the cavalry came riding.

Mr. Marchetti had pretty much given up, but his assistant took pity on us: “One thing we haven’t tried is radio. Let me see what I can do about getting an audition.” Eddie Cantor’s business manager said, “I think Eddie would love him.” I auditioned, and he did!

Cantor’s popular radio program also showcased stars and young actors like Deanna Durbin and Bobby Breen.

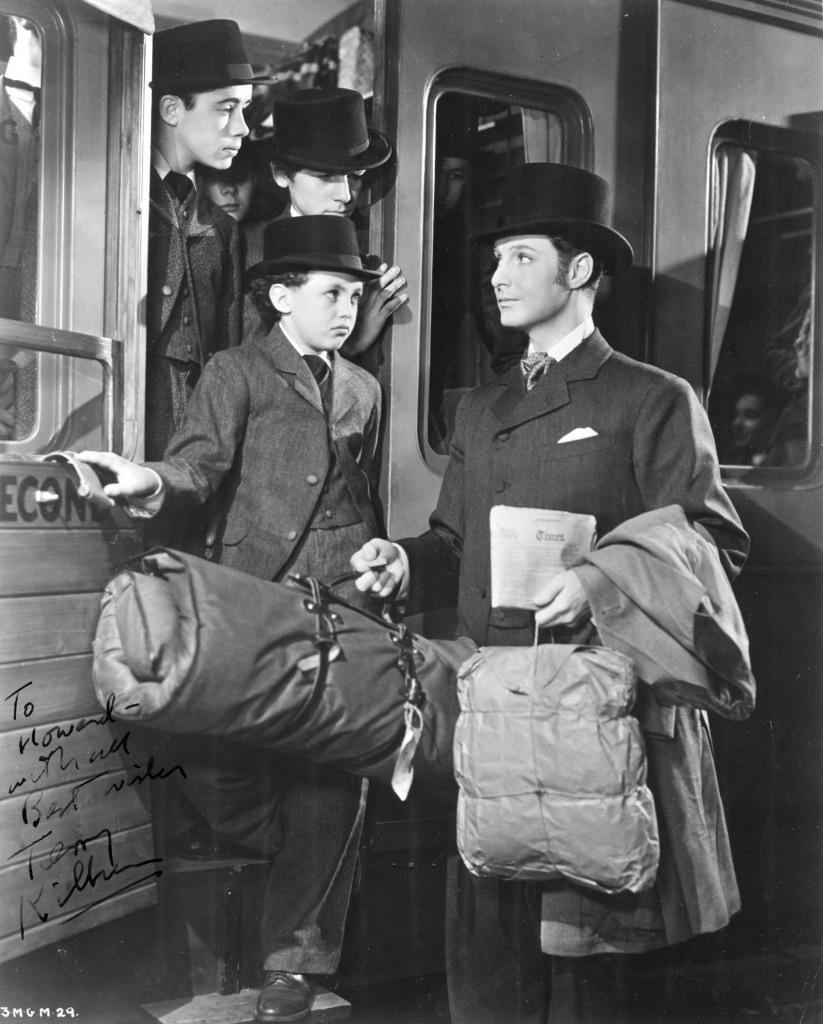

We were in rehearsal when a talent scout for MGM showed up. They were about to make a movie called Lord Jeff with Freddie Bartholomew and Mickey Rooney, based on the true story of those famous English orphanages, Doctor Bernardo’s Homes, where they trained young boys to go into the Royal Navy. There was a part for a little Lancashire boy, Albert Baker. The scout asked, “Can you do a Lancashire accent?” I said, “Aye I can, I can do it.” I’d learned “‘hae t’ talk like that,” sort of through my nose. “By goom, that’s champion!” “Oh my God!,” he said. “Sam Wood will just be thrilled.”

Even at that age, an actor will see a part and say, “Oh, that is my part.” Often they’re wrong, but sometimes they’re right, like Vivien Leigh thinking she was Scarlett. So I went to see director Sam Wood, and I did a thing for him, and he said, “The accent’s great, but I really wanted Alfalfa for this part.” Alfalfa could no more do that accent than fly, so that was out. But he wanted a kid like him. I was kind of a pretty little boy, so he said, “I’m sorry, but no.”

Fortunately, Terry’s mother had become friends with Lillian Rosine, MGM’s makeup specialist.

When I came back in tears Lillian said, “Oh, for God’s sake! What does Sam Wood think I’m here for? And she put me in her makeup chair, greased down my hair with Vaseline, blacked out one of my front teeth, put freckles on my face. I’d been crying, so I already looked horrible. Then she took me back and dragged me in and said, “There now, does he look ugly enough for you?” Sam Wood laughed and said, OK.”

One day while we were shooting, somebody came and said, “You’re wanted outside.” So I went out from the dark sound stage into the bright sunshine, and standing there was my father. I just ran and leaped into his arms, and we laughed and cried and it was incredible. Lord Jeff was quite a success. I got fabulous reviews that said, “The busman’s son from London steals the show.” It was thrilling. A dream come true–and my father was there, loving every minute of it.

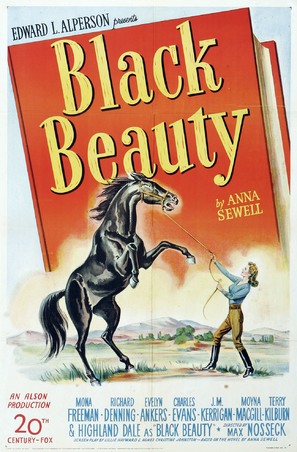

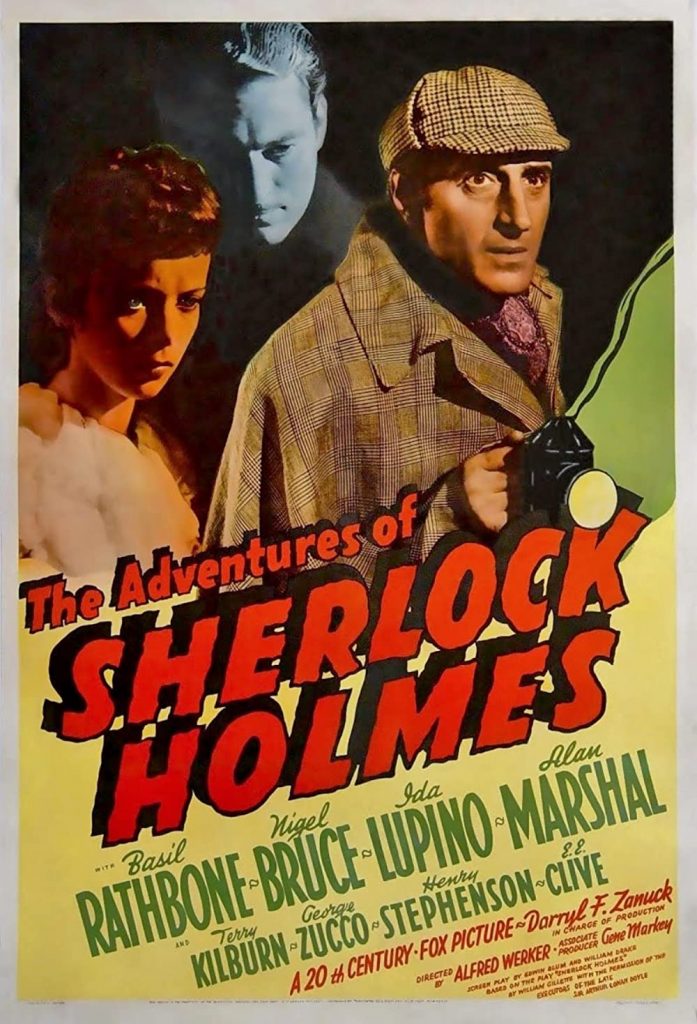

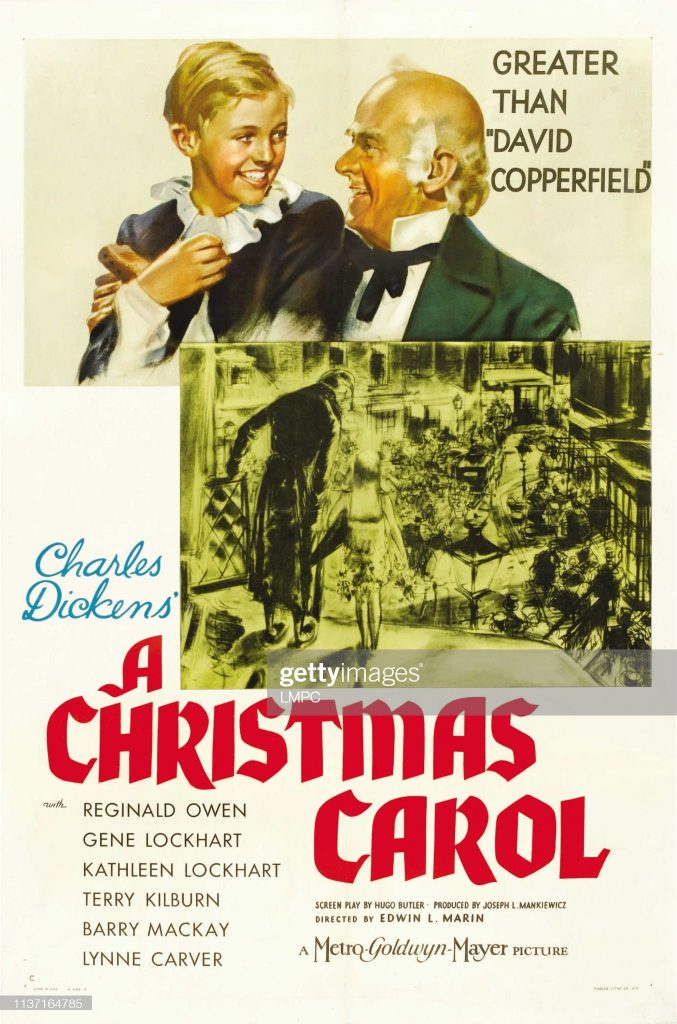

I also made A Christmas Carol in ’38, and played Tiny Tim. I’ll always remember going onto the set at the MGM lot the first day. I think it was London 1830, and the snow was coming down–they were actually Kellogg’s cornflakes, bleached or something, but it was so beautiful. Oh, you can imagine that for a kid who loved acting and being in fantasy, it was extraordinary.

He attended school at MGM, encountering Lana Turner, Kathryn Grayson, Anne Baxter–and, briefly, Judy Garland.

I sat next to Judy Garland for one day and just fell in love with her. She found my English accent absolutely hilarious. She had this wonderful laugh. And she had a charm bracelet with a tiny gold-framed picture of Clark Gable, because that song had made her a big success: “Dear Mr. Gable.”

He appeared in Sweethearts next, with Jeanette McDonald and Nelson Eddy, and was scheduled to be in a Topperfilm, when his part was cut.

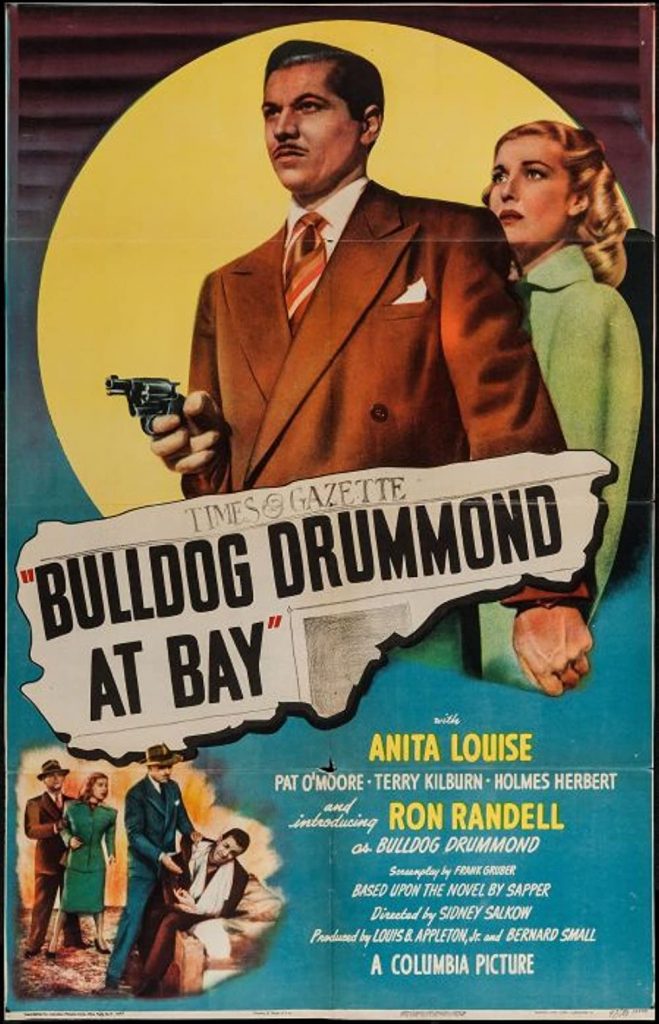

That didn’t bother me because by this time, just before Christmas, 1938, I was cast in Goodbye Mr. Chips, and was being sent back to England. Robert Donat would not come to this country for tax reasons. Greer Garson had been cast as the wife; she was a total unknown, had never made a movie in Hollywood. We went back on the Normandie. Greer Garson was on the ship, but she was up in first class.

“Chips” was professor Charles Edward Chipping whose career at Brookfield School progresses from young, stuffy classics prof, to beloved “Mr. Chips,” to Head of Brookfield during the Great War. Terry played four generations of Colley boys, and, as the youngest, Peter Colley III, says his iconic line to the elderly Chips who passes in his sleep recalling “his boys.” With Robert Donat, Greer Garson, John Mills, Paul Heinreid, from James Hilton’s novel.

Donat was wonderful, fascinating. I was old enough to see and respect what he was doing. Movie sets are notorious for fooling around. If it’s not much of a movie it doesn’t matter, but Donat realized this was the part of a lifetime, and he was very serous. When he got into playing the old Chips, he stayed in character the whole time, even between shots.

I tried to make each one of the four boys somewhat different, but I could only do as much as the scene allowed. Of course, I got to say, “Goodbye, Mr. Chips,” in this huge, wonderful close-up. Actors would give their souls for a close-up like that.

About that final shot: I wasn’t even supposed to be there since it was against the law for children to work that late. They just looked the other way, and it was almost midnight when I had that close-up.

Actors, like their characters, exist at the whim of chance and happenstance. For instance: What if Terry had known how to swim? What if Mickey Rooney had been taller?

There was a sequence in Lord Jeff where they wanted me to fall in the water. I couldn’t swim. I was terrified, even though they put a life jacket under my little sailor suit. I finally got up enough nerve, but only by looking first and jumping. That wasn’t what they wanted. I was so humiliated, so ashamed that I had disappointed Mr. Wood that my parents got me into swimming. I used to swim all the time, and I think that probably caused me to grow.

When I came back to Hollywood after making Chips, I was scheduled to be in a number of pictures with Mickey Rooney, playing his sidekick. But suddenly, instead of being twelve and looking ten, I was now twelve looking fourteen, and was as tall or taller than Mickey. My option was not taken up, and that began the next period of my life.

The above article can also be accessed online at “Lavender Magazine” here.