As a child actor, his large, expressive eyes, polite English tones and earnest sincerity made him world-famous in such classic films as How Green Was My Valley, Lassie Come Home and My Friend Flicka. With the end of adolescence, he fled Hollywood to study the craft of acting in New York and became an accomplished performer on stage and television, winning both Tony and Emmy awards. He won praise in such films as Cleopatra, The Poseidon Adventure and Planet of the Apes, and enjoyed a secondary career as a fine photographer.

He never married and said that his commitment was to his career, his friends and his voracious collecting of movie memorabilia. One of the most popular of actors, he maintained lifelong friendships with several of his co-stars. “He has more friends than anyone I know,” said the actress Ruth Gordon.

He was born in London, in 1928, his Scottish father an officer in the Merchant Marines. His Irish mother had once dreamed of going on the stage, and determined that her children should be in films. “My mother had complete control over us,” said McDowall late. “She would make all the decisions and pretend that my sister and I were making them.” He was only nine when he made his debut on the screen in Murder in the Family (1938), the first of 17 British films including I See Ice (1938) with George Formby, and two Will Hay comedies, Convict 99 and Hey Hey USA (both 1938).

In some he was only an extra (something his mother never admitted), but he had good roles in Just William (1939), an engaging version of Richmal Crompton’s children’s stories featuring McDowall as Ginger, and You Will Remember (1940), a biography of the composer Leslie Stuart (Robert Morley) in which McDowall’s character, a bootblack who becomes Stuart’s lifelong friend, was played in adulthood by Emlyn Williams. Williams wrote the screenplay for McDowall’s last British film, a morale-boosting piece about the country’s defence of its freedom through the ages, This England (1941).

Though some accounts state that McDowall was signed for Hollywood while still in England, the actor himself told the interviewer Michael Buckley that he sailed from Liverpool with his mother and sister on 24 September 1940 (his father was serving in the war) to live with friends of his mother’s in White Plains, New York. “My mother contacted agents, one of whom sent me to the MGM office to test for The Yearling. They said that I was too English, but that at 20th Century-Fox they were looking for a child for How Green Was My Valley.” A test reel was made in New York and William Wyler, then scheduled to direct the film, saw it and asked for the child to be brought to California so that he could do a test himself.

McDowell was fifth-billed as a cabin boy, and his sister Virginia played a small role as the postmistress’s daughter, in this Fritz Lang thriller based on Geoffrey Household’s book Rogue Male. How Green Was My Valley was then re-activated, with John Ford now directing and McDowell playing the pivotal role of Huw, the young boy through whose eyes we see the disintegration of a Welsh mining family. His part was originally to be brief, with Tyrone Power playing the character as an adult, but the studio chief Darryl F. Zanuck, after early script conferences, wrote in a memo to his staff: “I feel that our only chance of capturing the right mood is to see the story through the eyes of Huw the boy . . . keeping him a young boy throughout the story is essential.”

The Oscar-winning film turned out to be a masterpiece, and McDowall described Ford as “a miraculous director. He was probably the most masterful film- maker I ever worked with.” As the youngster who is forced to leave school and work in the mines, McDowall projected a winning combination of wide- eyed sensitivity and inner grit. “Little Roddy McDowall is superb,” said the New York Times.

It was the first of several roles in which he played a child who had to shoulder responsibility all too soon in life, such as the courageous lad who gets a vital message to a war correspondent before being killed by the Nazis in Confirm or Deny (1941) and the boy who inspires a self- centred bachelor to shepherd a batch of refugee children from France to England in The Pied Piper (1942). He later told the former child star turned writer Dickie Moore that, after the release of his films, “the kids on the block wouldn’t play with me. They wouldn’t even talk to me. Double jeopardy because I was English and talked funny and also because I didn’t go to school.” McDowall played several film heroes as a child – he was the young Tyrone Power in Son of Fury (1942), Gregory Peck in The Keys of the Kingdom (1944), and Peter Lawford in The White Cliffs of Dover (1944).

In 1943 he made one of his best-remembered films, Lassie Come Home, in which he is forced to part with his beloved dog, but is movingly reunited with the animal after it makes its way home from Scotland to Yorkshire. McDowall’s portrayal was appealingly devoid of precocity or mawkishness and he was similarly effective displaying love for his horse in two popular films, My Friend Flicka (1943) and its sequel Thunderhead, Son of Flicka (1945). “I loved Pal, the dog who played Lassie,” said the actor years later. “He was a lot smarter than some of the people I know. But I hated the main Flicka horse; she was mean, kept stepping on my feet.”

Lassie Come Home marked the start of a friendship with his co-star Elizabeth Taylor which was to be lifelong, and when he played Jane Powell’s boyfriend in the musical Holiday in Mexico (1946) it was the start of another. “Roddy’s been like a brother to me,” Powell wrote.

In the mid-Forties, after making Molly and Me (1945) with Gracie Fields (“a woman of extraordinary spirit, courage, stamina and fabric. I worshipped her and stayed friendly with her until she died”) McDowall was released from his Fox contract: “At 17 my childhood career was over. My agent told me I would never work again, because I’d grown up.”

He turned to the theatre, making his stage debut in Young Woodley (1943) in Westport, Connecticut, then did a six-month vaudeville tour. In 1947 he played Malcolm in Orson Welles’s production of Macbeth in Salt Lake City, and played the same role in the subsequent film. He regarded Welles as “too clever by half. He did a lot of damage to his own genius, for some perverse reason that I don’t particularly understand.”

Joining a minor studio, Monogram, McDowall played David Balfour in Kidnapped (1948), in which his mother had a small role, but his six other Monogram films (on which he was also executive producer) were mediocre. He later stated that he would have attended college had he been able:

There was not enough money. Who was going to do the work? I had no money,

though I had made over a hundred thousand a year. Had my father not been so mesmerised by my mother I would have had every dime I ever made. My father was scrupulously honest, but mother had such control over him that he was powerless.

Jane Powell described Wynn as

a classic stage mother . . . I . . . realised it was terribly important for Roddy to get away from home. She was destroying him as a man, as a person and as a talent. The whole family was under her thumb. Every time the family didn’t do what she wanted, she’d feign a heart attack.

In 1952 McDowall gave his Los Angeles home to his parents and went to New York to study acting with Mira Rostova and David Craig (“I was not without talent, but didn’t seem to have any craft”) and next year made his Broadway debut in a revival of Shaw’s Misalliance.

McDowall had made his television debut in 1951 on Robert Montgomery Presents, and later stressed the importance of television. “It was in that arena that I had the chance to fail and grow. Without it, I don’t think I’d have had the opportunity to make a bridge between one period of my life and the other.” He was a guest on many major series, starred in productions of Heart of Darkness (1958) and Billy Budd (1959) and won an Emmy award for his performance as Philip, son of Alexander Hamilton in Not Without Honour (1960). “Working in television,” he said, “you could be in two or three stage flops a year and not starve.”

Nineteen fifty-five was to be “the big turning-point” of his adult career, with four highly praised stage performances. He played in The Doctor’s Dilemma off-Broadway, Ariel in The Tempest and Octavian in Julius Caesar in Stratford, Connecticut, and in October opened as Ben Whitledge, the zealous best friend of the bumpkin hero of Ira Levin’s hit comedy No Time for Sergeants. In 1957 he co-starred with another former child actor, Dean Stockwell, in Meyer Levin’s gripping play based on the Leopold-Loeb thrill-killing, Compulsion, playing Artie Strauss (the Loeb character).

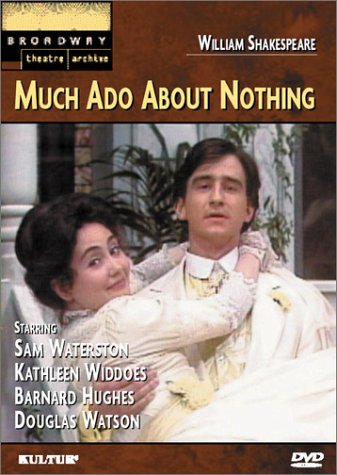

He finally returned to the screen in 1960, with roles in The Subterraneans and Midnight Lace. The same year he rang the stage director Moss Hart to ask for the role of Mordred in the upcoming Lerner-Loewe musical Camelot. The composers gave him a song solo, “The Seven Deadly Virtues”, at the last minute. McDowall and Richard Burton both left Camelot after a year to join Elizabeth Taylor in Rome to film Cleopatra (1963), McDowall as the evil Octavian receiving reviews which were second only to Rex Harrison’s.

During the long shooting schedule, he was given time off to film his part of Private Merris in The Longest Day (1962), and was now in constant demand for both film and television work. Films included The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965, as Matthew) and George Axelrod’s offbeat comedy Lord Love a Duck (1966). In 1966 he played a CIA agent in The Defector, the last film made by his longtime friend Montgomery Clift, who later stated that he could never have finished the film without McDowall’s moral support.

In 1967 McDowall played the intelligent talking ape Cornelius in Planet of the Apes, and was in three of the four sequels plus a television series based on the film. He missed the first sequel, Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970) because he was in London directing a film, though he did provide the voice for one of the apes. His directorial effort Tam Lin (later retitled The Devil’s Widow) starring Ava Gardner as an old witch who uses her powers to surround herself with young friends, was not well received. He was Acres the steward in the hit disaster movie The Poseidon Adventure (1972) – its director, Ronald Neame, had been cameraman on McDowall’s first released film, Murder in the Family.

His performance as a nasty lawyer in The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972) was lauded and he followed with John Hough’s horror film The Legend of Hell House. An admirer of Barbra Streisand, he played her assistant in Funny Lady (1975), and he did a cameo as an old gypsy woman in Rabbit Test (1978) as a favour to its director, his close friend Joan Rivers. More recent films included the comedy-thriller Fright Night (1985) and its sequel, and Overboard (1987), on which he was executive producer as well as playing butler to Goldie Hawn.

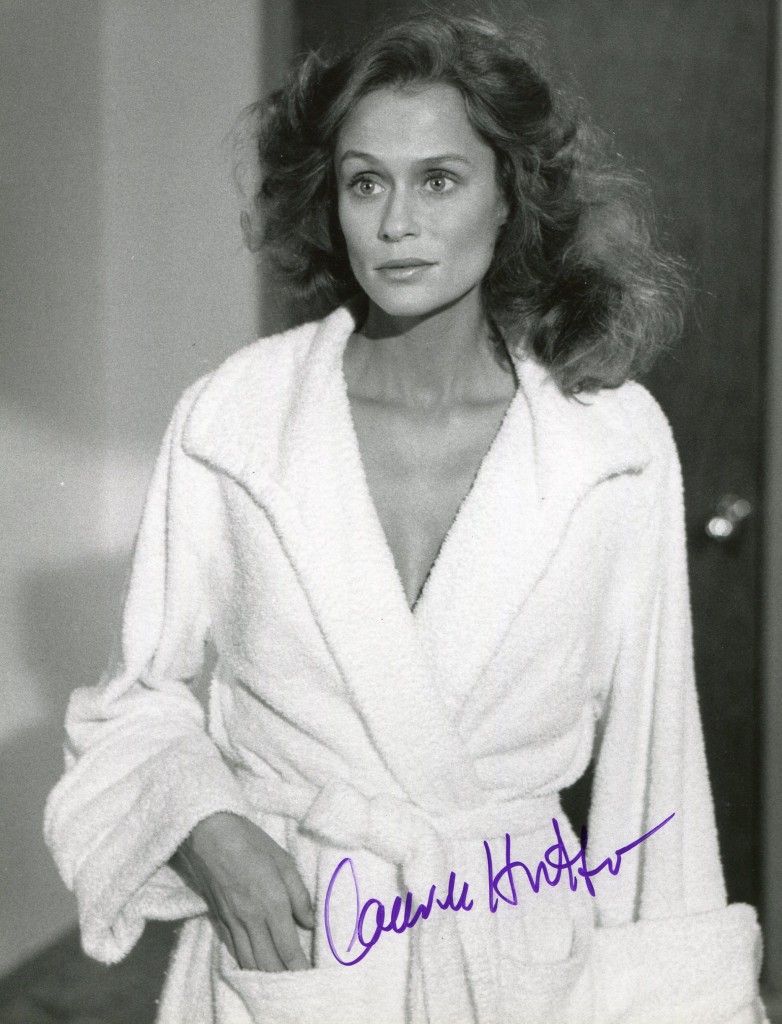

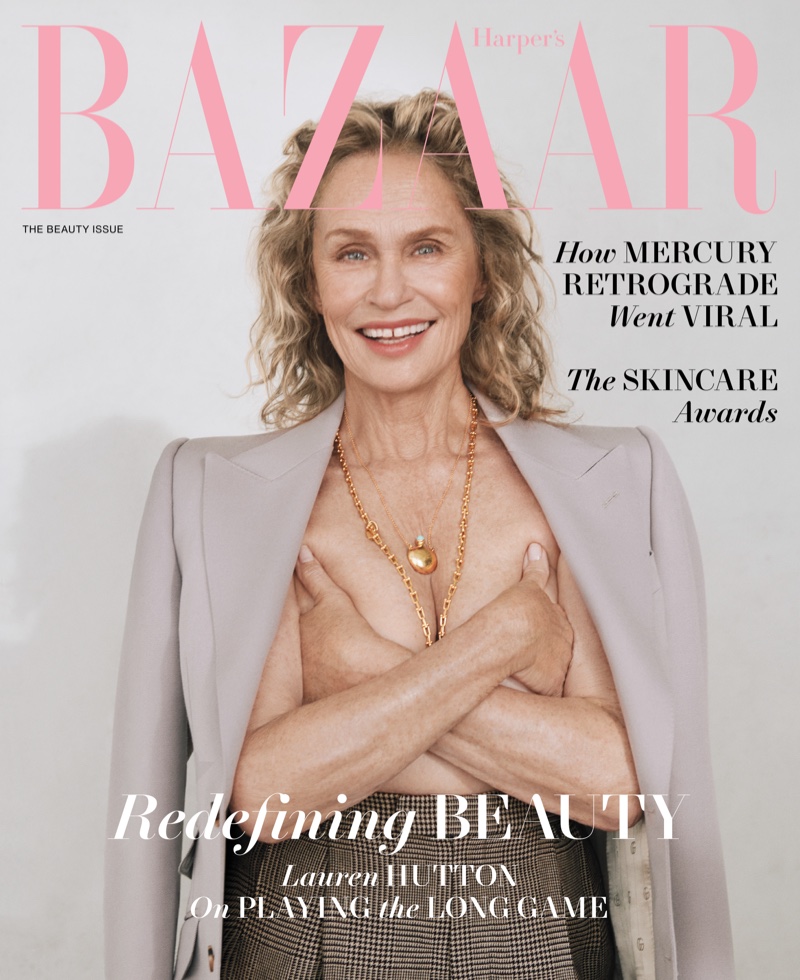

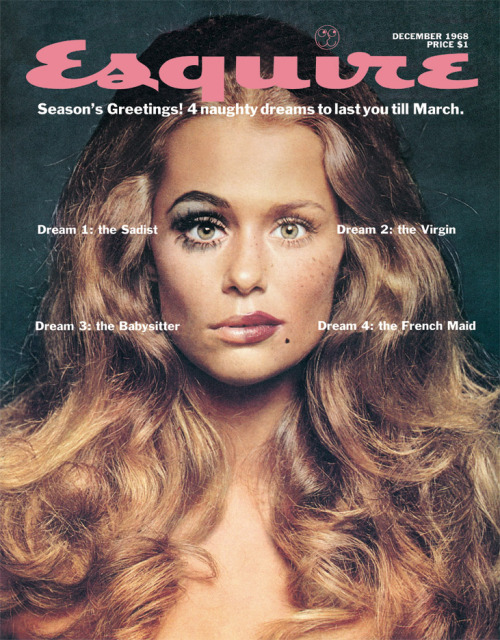

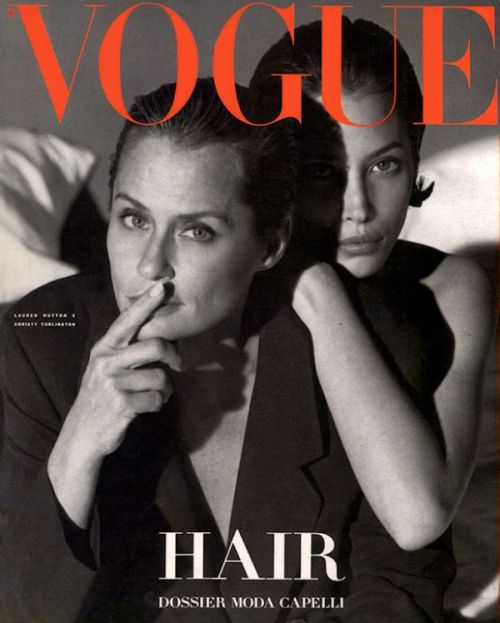

For many years McDowall also pursued another career. From childhood, he had a great passion for photography and eventually the actress Gladys Cooper persuaded him to do something commercial with his talent. One of his earliest assignments was to shoot pictures on the set of Cleopatra, after which he worked for Look, Life, Harper’s Bazaar and Architectural Digest. In 1966 he published his first book, the best-selling Double Exposure.

He loved acting, and until recently was still touring the theatres of America in such plays as Harvey and Dial M For Murder. Some years ago he told a columnist,

I don’t regret any part of my childhood career. I loved it! The problem for a child actor is to overcome one’s initial success. All I’m trying to do now is the best I can with what I’m doing. I hope I can keep working as long as possible.

Roderick Andrew Anthony Jude McDowall, actor: born London 17 September 1928; died Los Angeles 3 October 1998.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.