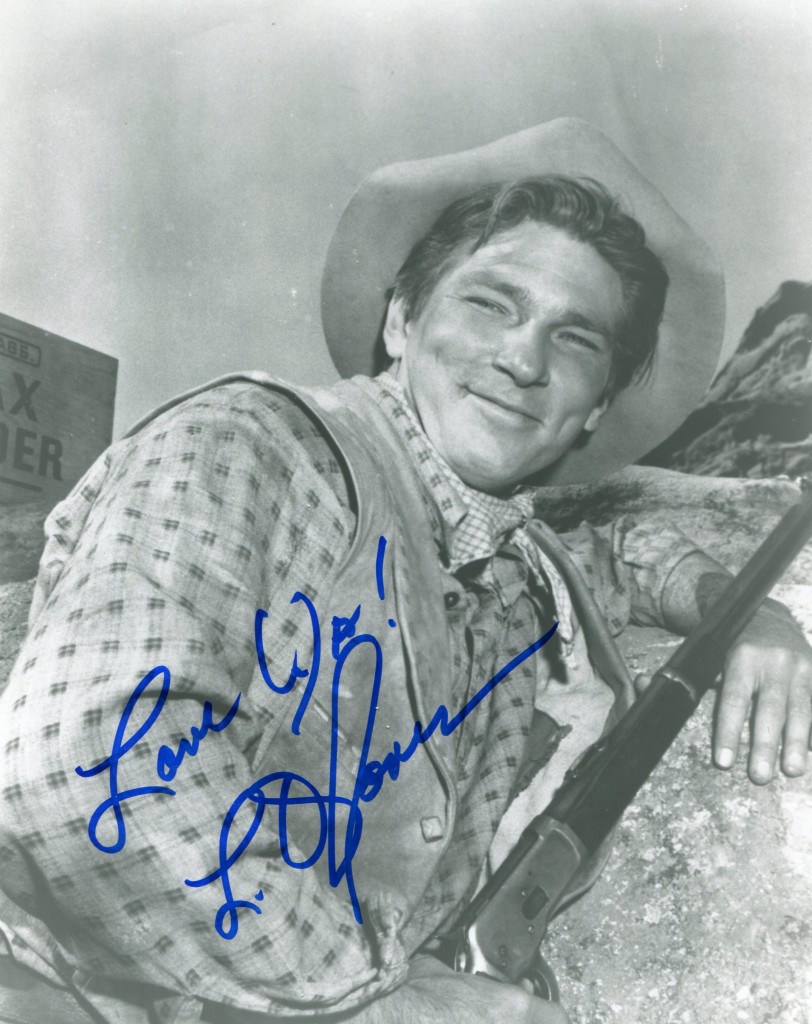

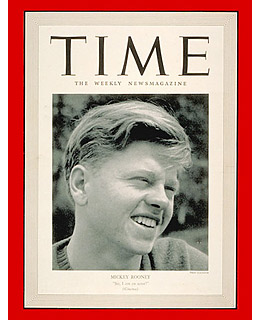

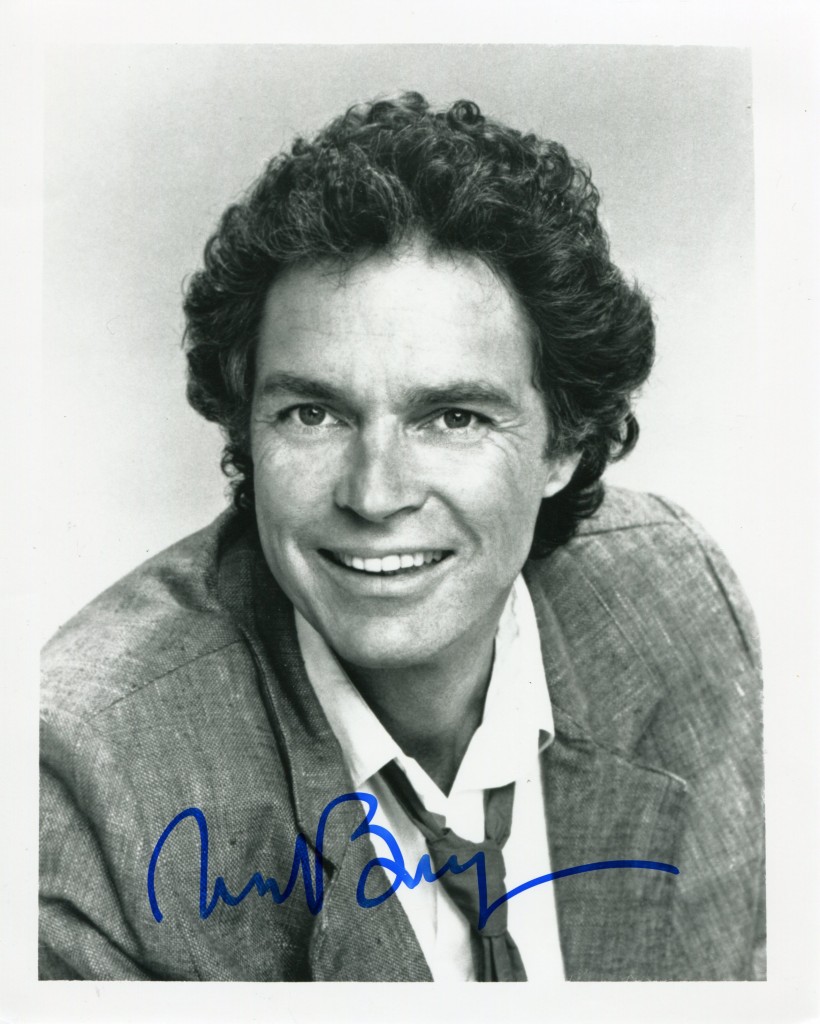

Mickey Rooney was born in n1920 in Brooklyn, New York. As a child actor he acted under the name Mickey McGuire. By the late 1930’s he acted as Mickey Rooney and had a contract with MGM where he made many musicals with Judy Garland and also acted the title role in the Andy Hardy series. His other films include “Words and Music” in 1948 and “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” in 1961. Mickey Rooney died in April 2014.

Mickey Rooney was a little man who enjoyed a big career and a larger-than-life persona. Born into a family of vaudeville performers, he was pushed on stage before he could talk and never let up, appearing in hundreds of movies, TV shows, plays, casinos and gossip columns. He had a hunger for life and work that belied his small stature, marrying eight times, earning and losing millions of dollars on several occasions, and seemingly accepting any invitation to perform, whether it was a dinner theater or the Academy Awards. Outliving most of his Golden Age contemporaries, he carved out a unique place in show business history that spanned generations of fans. And even though his career reached its peak in the 1930s with his onscreen partnership with Judy Garland, he continued to win awards and accolades until his death on April 6, 2014.

Mickey Rooney was born Joseph Yule, Jr. on Sept. 23, 1920 in Brooklyn, NY. His name was plain but his family was colorful. Rooney’s father, Joe Yule, was a Scottish-born vaudeville performer and his mother, Nell, was a chorus girl from Kansas City, MO. Soon after his first birthday Rooney was appearing on stage with his parents and traveling around the country by train. The vagaries of show business did not encourage domestic bliss, leading to Rooney’s parents breaking up in 1924. Nell took custody of her son and, in the grand and often grotesque tradition of frustrated performers, channeled her hopes and dreams into her child. She moved with her son out to California, where she balanced managing a tourist home and overseeing Rooney’s growing career. She was not skilled at either, going broke and moving back and forth between Los Angeles and Kansas City to receive financial help from her family. It was a grim existence until Rooney got his big break playing, ironically, a midget. The movie “Not to Be Trusted” (1926) was not a film classic, but it jump-started Rooney’s career.

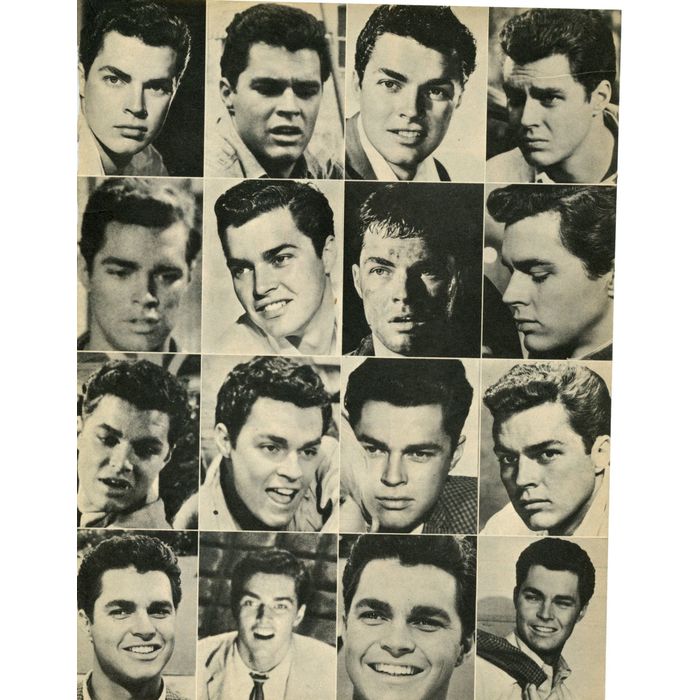

Nell used some old fashioned derring-do to land Rooney his next job. Learning that the popular comic strip “Mickey McGuire” was going to be turned into a series of short films, she put her son up for the part. Rooney was still named Joe Yule, Jr. at this point, but Nell offered to legally change his name to Mickey McGuire so that the producers of the films could circumvent paying the writer of the comic strip royalties. This cold-hearted ploy did not work, but Nell still had her son’s name changed to the apparently more marquee-friendly “Mickey Rooney.” Regardless, Rooney got the part and went on to star in dozens of shorts based on the McGuire character, starting with “Mickey’s Circus” (1927). And it truly was a circus, as Rooney worked non-stop for the next 10 years until finally wrapping up the McGuire series with “Mickey’s Derby Day” (1936).

The “Mickey McGuire” movies made Mickey Rooney a star, but his next film series propelled him into the top tier of Hollywood actors. Although he had received good reviews for his work in several features, most notably as Puck in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” (1935), his appearance as Andy Hardy in “A Family Affair” (1937) changed his life forever. Playing the son of Judge James K. Hardy (Lionel Barrymore), Rooney helped MGM’s little B-movie become a monster hit. He played the same role in 13 more homespun “Andy Hardy” films produced between 1937 and 1946, giving venerable MGM one of its most profitable franchises. The early movies were about the entire Hardy clan, but by the fourth film in the series, “Love Finds Andy Hardy” (1938), Rooney’s exuberant personality had pushed his character to the top of the marquee. His portrayal of the all-American boy became an archetype of old-fashioned, Midwestern wholesomeness.

Ironically Andy Hardy’s squeaky-clean image was quite a contrast to the real-life Rooney. As he became more famous, the actor became more reckless, known around Hollywood for his late night carousing and numerous affairs. The most scandalous liaison came to light years later in Rooney’s autobiography, in which he claimed that in 1938, when he was just 18, he had a relationship with the A-list actress Norma Shearer, then 38, and the widow of MGM’s “Boy Wonder” production chief, Irving Thalberg. Louis B. Mayer, the head of MGM and a mentor to Thalberg, used his considerable influence to end the affair and keep it from the press. Whether this was out of loyalty to his late protégé or merely a cynical attempt to keep Rooney’s public image more in line with that of Andy Hardy, was impossible to say, but it definitely allowed the actor to continue starring in MGM’s cash cow franchise without any backlash from his adoring fans.

While Rooney’s offscreen romances often got him into trouble, his onscreen relationship with Judy Garland became one of the most famous partnerships in film history. First appearing together in “Love Finds Andy Hardy,” where the then starlet had a guest appearance, they starred together as equals in the musical “Babes in Arms” (1939), directed by the great Busby Berkeley. The movie was a hit and the couple’s chemistry and bright-eyed enthusiasm was real. They became friends and stayed close until her tragic death in 1969. Together they made numerous popular features together, including several more Andy Hardy movies and Busby Berkeley musicals, among them “Strike up the Band” (1940) and “Babes on Broadway” (1941) – most of which were of the “Comon kids, let’s put on a show!” variety.

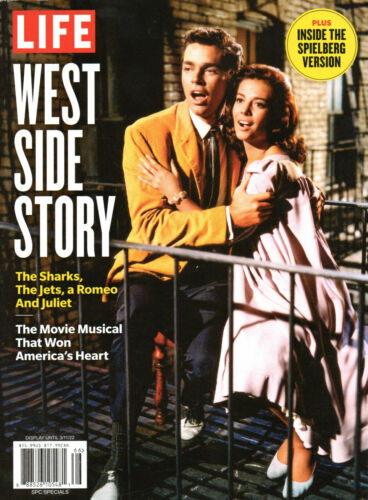

But Rooney’s popularity was not contingent upon Garland, who shot to worldwide fame playing Dorothy in “The Wizard of Oz” (1939). Rather, his appeal came from his infectious energy and innate fearlessness as an actor. Whether sharing the screen with giants like Spencer Tracy and Lionel Barrymore in “Captains Courageous” (1937), and again with Tracy in “Boys Town” (1938) – for which Tracy received an Academy Award – Rooney more than held his own. And, of course, the public adored him. From 1939 through 1941, Rooney was the number one box office actor in the United States, as he would proudly continue to remind the world even years later. As America entered World War II, his Andy Hardy films continued to be wildly popular and Rooney worked steadily. He somehow found the time to marry and divorce the gorgeous starlet Ava Gardner (the future Mrs. Frank Sinatra) between 1942 and 1943 before hitting his professional peak opposite Elizabeth Taylor in the horse racing drama, “National Velvet” (1944). But when Rooney was drafted into the military, everything changed.

During WWII, Rooney went to war to entertain the troops, only serving 21 months. But while he did not suffer any physical harm while abroad, when he came home his career was damaged. Post-war America was less innocent than the one that had embraced Andy Hardy. Moreover, Rooney was now 26 years old and thus, a little too long in the tooth to continue playing teenagers. His professional life started a long, slow slide. While he was never at a loss for work, the quality of the material was inferior to his earlier films. To make matters worse his onscreen partnership with Judy Garland came to a close with the musical “Words and Music” (1948). Rooney gamely soldiered on, while his former co-star’s career eclipsed his. Not only because he loved to work but also because he had to. He fit in a few more failed marriages, including one to actress Martha Vickers, while trying to find good parts to pay his alimony. There were bright spots like the Korean War drama “The Bridges at Toko-Ri” (1954), but more often than not Rooney did whatever slop he was offered, including “The Fireball” (1950) and “The Atomic Kid” (1954). Like many movie stars before him whose stars were starting to fade, he turned to television.

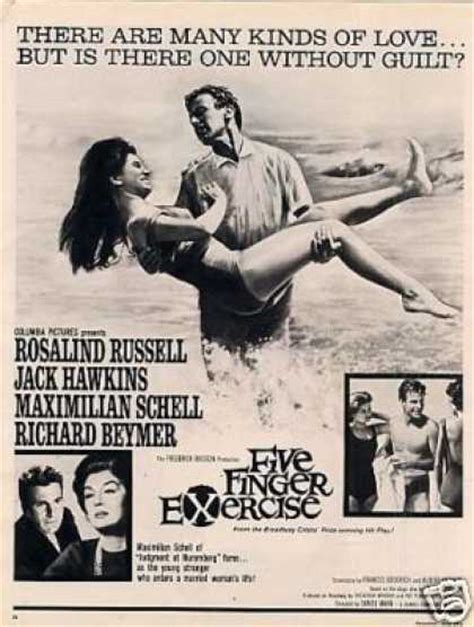

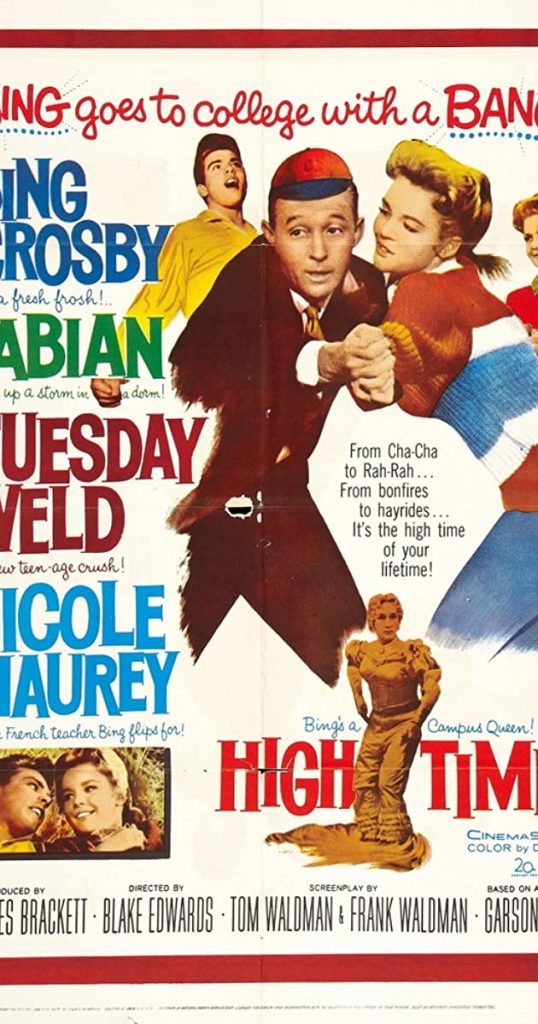

“The Mickey Rooney Show” (NBC, 1954-55) – also known as “Hey, Mulligan” – featured Rooney playing a fast-talking teenager. The fact that Rooney, in his mid-30s, was essentially reprising his Andy Hardy character may have had something to do with the show’s cancellation after 39 episodes. Still, it had to be more satisfying work than starring opposite Francis the Talking Mule in “Francis in the Haunted House” (1956). With live television attracting some of the best young directors and writers, Rooney kept returning to the small screen. He scored an artistic triumph and an Emmy nomination in “The Comedian” (1957), an episode of the famous series “Playhouse 90” (CBS, 1956-1961). The late 1950s were the Golden Age of live TV and it gave Rooney’s career a shot in the arm. He continued to work on TV shows like “Alcoa Theater” (NBC, 1957-1960) while landing the occasional film role. He was a natural fit for the film “Baby Face Nelson” (1957), playing a murderous gangster who looks like a choirboy and he (mercifully) put the Andy Hardy series to rest with the feature “Andy Hardy Comes Home” (1958). Finally, in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” (1961) he found a role he could sink his teeth into. Unfortunately, they were a set of fake buckteeth that set off the biggest controversy of his career. Blake Edwards, who had worked on Rooney’s TV show as a writer, directed “Breakfast at Tiffany’s,” an adaptation of Truman Capote’s novel. The director and actor were close friends, and perhaps this influenced Edwards not reigning in Rooney’s broad performance of a stereotypical, bucktoothed Japanese man. Rooney’s overacting marred an otherwise popular and well-reviewed film, but his sub-par work was the least of his problems.

Rooney’s latest marriage – his fifth – was falling apart during this period. He had married the beauty queen and B-movie actress, Barbara Ann Thomason (a.k.a Carolyn Mitchell), in 1958. While Thomason had put her career on hold to raise the kids, Rooney worked non-stop to support his ex-wives, his gambling habit, and a growing family. He tried directing, but the dismal comedy “The Private Lives of Adam and Eve” (1960) should have stayed private. Hack TV work kept the money rolling in, and there was a cinematic bright spot with his supporting turn in the drama “Requiem for a Heavyweight” (1962), but lightweight fluff like “How to Stuff a Wild Bikini” (1965) was more representative of Rooney’s output at the time. Now in his forties, he nevertheless continued his extra-marital affairs; a favor returned by his young wife. When Rooney was in the Philippines filming the war movie “Ambush Bay,” he was literally ambushed by tragic news: Thomason’s jealous lover had murdered her in the Rooney’s Brentwood home. Rooney returned to the states and a cauldron of controversy. The sordid and dysfunctional personal life of the man who had played the all-American boy became fodder for the tabloids and permanently tarnished Rooney’s image. He continued plugging away in mediocre movies like “Skidoo” (1968) in an attempt to keep the demons at bay, but Judy Garland’s death from an accidental overdose of barbiturates in 1969 was an even worse punishment.

Nearing fifty and rocked by personal tragedy and professional disappointment, it would have been easy for Rooney to pack it in. But Rooney’s vaudeville training had instilled in him a powerful ethos that “the show must go on.” He kept working throughout the 1970s, seemingly in any production that would pay him. Wary of more controversy, he passed up the role of the racist Archie Bunker in the TV classic “All in the Family” (CBS, 1971-79); instead turning to family friendly fare like “Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town” (ABC, 1970), “The Year Without a Santa Claus” (ABC, 1974), and “Journey Back to Oz” (1974). An inveterate gambler and horse racing aficionado, his love of the ponies found artistic triumph in the film classic “The Black Stallion” (1979). Rooney turned in one of his great performances playing Henry Dailey, a once successful horse trainer who gets one last shot at immortality. Rooney received some of the best reviews of his career for a role that was a metaphor for his own creative resurrection.

Rooney followed up his Academy Award-nominated performance in “The Black Stallion” with a starring role opposite dancer Ann Miller in the long running Broadway hit “Sugar Babies” (1970-1982). Earning a Tony nomination for his stage work, he scored again with an Emmy win playing a mentally handicapped man in the TV drama “Bill” (CBS, 1981). It was the high-water mark of Rooney’s career: film, stage, and TV work of the highest quality all within a couple years and late in the game. And while he did not hit such a hot streak again, Rooney had proven to his loyal fans and vocal detractors that he still had the goods. He continued working steadily on TV and in movies such as “Night at the Museum” (2006), as well as the theater. He even traveled the world in a multi-media live stage production called “Let’s Put on a Show!” recounting his long, eventful life in show business to his still sizable fan base.

In 2011, Rooney accused his stepson Chris Aber of committing elder abuse against him, including acts of financial malfeasance; Rooney’s eighth wife and Aber’s mother, Jan Rooney, denied the allegations. Rooney testified about elder abuse before a Senate committee in March 2011 and won a multi-million dollar settlement against Aber. That same year, Rooney made his final feature film appearance with a cameo role in Jason Segel’s hit franchise reboot “The Muppets” (2011). Rooney died of undisclosed natural causes on April 6, 2014.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online

here.